Reflections on Editing the Journal of Finance, 2006-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORK EXPERIENCE Current Positions • the Wharton School

JOÃO F. GOMES Address: Finance Department The Wharton School University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104 Phone: 1 215 898 3666 Email: [email protected] Links: Web: https://fnce.wharton.upenn.edu/profile/gomesj/ SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/cf_dev/AbsByAuth.cfm?per_id=239587 Google: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=kdXbXXIAAAAJ&hl=en 4 February 2019 WORK EXPERIENCE Current Positions • The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 1997- current o Howard Butcher III Professor of Finance, 2010 - current Previous Positions • Visiting Professor of Finance, London Business School (UK), 2009- 2011 • Visiting Scholar, University of British Columbia (Canada), 2003 • Visiting Professor of Economics, Nova SBE (Portugal), 1997-1999 • Research Affiliate, Center for Economic Policy Research (UK), 1999 –2004 • Economic Consultant, Ministry of Industry (Portugal), 1991 – 1992 Editorial, Consulting and Advisory • Visiting Research Associate, U.S. Federal Reserve (various), 1999, 2014-current • Editor, Economics Letters, 2014 - current • Associate Editor, Journal of Monetary Economics, 2014 - current EDUCATION Degrees • Ph.D., University of Rochester, 1997 • M.A., University of Rochester, 1996 • B.S., Nova SBE (Portugal), 1991 RESEARCH Major Publications • João Gomes, Marco Grotteria and Jessica Wachter, Cyclical Dispersion in Expected Defaults, conditionally accepted, Review of Financial Studies, May 2018 • João Gomes and Lukas Schmid, Equilibrium Asset Pricing with Leverage and Default, forthcoming, Journal of Finance, December -

Curriculum Vitæ

JOHANNES STROEBEL [email protected] http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~jstroebe/index.html EMPLOYMENT 2013 – New York University, Leonard N. Stern School of Business David S. Loeb Professor of Finance, 2019 – Professor of Finance, 2018 – Associate Professor of Finance (with tenure): 2016 – 2018 Assistant Professor of Finance: 2013 – 2016 2012 – 2013 University of Chicago, Booth School of Business Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Economics OTHER AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Center for Global Economy and Business, NYU Stern; Research Director, Global Finance 2019 – Volatility and Risk Institute, NYU Stern; Research Director, Climate Finance Research 2016 – Salomon Center, NYU Stern; Research Director, Household Finance Program 2015 – National Bureau of Economic Research, US, Research Associate Asset Pricing, Corporate Finance, Economic Fluctuations & Growth, Monetary Economics 2015 – CESifo, Germany, Research Fellow 2014 – Center for Economic Policy Research, UK, Research Affiliate Financial Economics Program EDUCATION 2007 – 2012 Ph.D. Economics, Stanford University Advisers: Caroline Hoxby, Monika Piazzesi, Martin Schneider, John Taylor 2003 – 2006 B.A. Philosophy, Politics and Economics, Merton College, Oxford, First Class Honors EDITORIAL RESPONSIBILITIES 2020 – Associate Editor, Econometrica 2019 – Associate Editor, The Journal of Political Economy 2017 – Foreign Editor, The Review of Economic Studies 2016 – Associate Editor, The Journal of Finance WORKING PAPERS Social Networks Shape Beliefs and Behavior: Evidence from Social Distancing -

Lasse Heje Pedersen

LASSE HEJE PEDERSEN CURRICULUM VITAE, UPDATED NOV., 2013 DANISH CITIZEN, US PERMANENT RESIDENT, BORN OCT. 3, 1972 WEB: www.lhpedersen.com ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS New York University Stern School of Business John A. Paulson Professor of Finance and Alternative Investments, 2009-present (on leave). Professor of Finance, 2007-2009. Associate Professor of Finance, with tenure, 2005-2007. Charles Schaefer Family Fellow, 2003-2006. Assistant Professor of Finance, 2001-2005. Copenhagen Business School Department of Finance, FRIC Center for Financial Frictions, 2011-present. University of Chicago Milton Friedman Institute Fellow, Fall 2010. IGM Visiting Professor, Booth School of Business, Spring 2010. Columbia Business School Visiting Professor, Spring 2009. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Monetary Policy Panel, 2010-2011. Liquidity Working Group, 2009-2011. Academic Consultant, 2004-2007. American Finance Association Director, 2011-present. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Research Associate, 2006-present. Faculty Research Fellow, 2004-2006. Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Research Affiliate, 2004-present. Editorial Boards Quarterly Journal of Economics, Associate Editor, 2011-present. Journal of Finance, Associate Editor, 2006-2012. Journal of Economic Theory, Associate Editor, 2005-2012. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, Associate Editor, 2010-2012. Lasse H. Pedersen 1/11 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE AQR Capital Management, LLC Principal, 2009-present. Vice President, 2007-2008. Consultant, 2006-2007. FTSE Advisory Board, 2009-present. NASDAQ OMX Economic Advisory Board, 2008-2011. State Street Bank, State Street Global Markets Consultant, 2005-2007. Benchmark Metrics Advisory Board, 2006-2008. Speaking Engagements Misc. compensated and non-compensated speaking engagements: see below. EDUCATION Stanford University, Graduate School of Business Ph.D. -

Curriculum Vitae

Arthur G. Korteweg June 22, 2021 Hoffman Hall, Room 721 [email protected] Marshall School of Business https://www.marshall.usc.edu/personnel/arthur-korteweg University of Southern California Phone: (213) 740-0567 3670 Trousdale Parkway Fax: (213) 740-6650 Los Angeles, California, 90089 Work Experience University of Southern California Marshall School of Business Associate Professor of Finance and Business Economics, 2017-present. Jorge Paulo and Susanna Lemann Chair in Entrepreneurship, 2021-present. Dean’s Associate Professor in Business Administration, 2017-2020. Assistant Professor of Finance and Business Economics, 2014-2017. Stanford University Graduate School of Business Associate Professor of Finance, 2012-2014. Assistant Professor of Finance, 2007-2012. Younger Family Faculty Scholar, 2011-2012. Graduate School of Business Trust Faculty Scholar, 2010-2011. Education University of Chicago Graduate School of Business Ph.D. in Finance, 2007. M.B.A., 2007. Tilburg University Ph.D. in Finance (not completed), 2001-2002. M.A. in Economics (cum laude), minor in Finance, 2001. Publications Korteweg, A., and B. Sensoy, How Unique is VC’s American History? Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming. Ewens, M., Gorbenko, A., and A. Korteweg, Venture Capital Contracts, Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming. Korteweg, A., M. Schwert, and I. Strebulaev, 2020, Proactive Capital Structure Adjustments: Evidence from Corporate Filings, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, forthcoming. Korteweg, A., 2019, Risk Adjustment in Private Equity Returns, Annual Review of Financial Economics, 11, 131-152. Korteweg, A., and M. Sørensen, 2017, Skill and Luck in Private Equity Performance, Journal of Financial Economics, 124(3), 535-562. Korteweg, p.2 of 6 - Fama/DFA Prize (2nd place) for Best Paper in Capital Markets and Asset Pricing. -

Message from the Dean

MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN Since becoming Dean of New York We, therefore, are seeking students University’s Stern School of Business, who have the curiosity and creativity I have made it my mission to lead its to anticipate the pressing questions ascent to the next level of excellence and issues that will shape the future — into the handful of pre-eminent of business education. business schools in the nation. Our location is unmatched, within At the heart of this strategy is easy reach of Wall Street and the research and scholarship. headquarters of many major corpo- Today, the Stern School of rations, allowing us to use New York Business is continuing to build upon City as our laboratory for learning. its tradition of research by attracting Our research centers, which produce not only the best and brightest schol- theoretical insights that guide mana- ars of tomorrow. In this past year, gerial and public policy decision- I urge you to explore our program Professors Adam Brandenburger, making, promote a dynamic dialogue thoroughly and to consider what is Thomas Sargent and Russell Winer with the business and academic com- contained in this book very carefully. have joined our faculty, and we are munity. For example, the Center for Review the testimonials from alumni, determinedly pursuing other Law and Business and the Ross weigh the support provided and renowned scholars and teachers. Institute of Accounting Research track the career paths of those who A vital component of our mission have been in the forefront of research have gone before you. A PhD from is to expand the intellectual parame- and discussion surrounding the issue NYU Stern can open academic doors ters of a business education and of corporate governance. -

Report of the Editor of the Journal of Finance for the Year 2011

THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE • VOL. LXVII, NO. 4 • AUGUST 2012 AMERICAN FINANCE ASSOCIATION Report of the Editor of the Journal of Finance for the Year 2011 CAMPBELL R. HARVEY, EDITOR I AM HAPPY TO REPORT that 2011 was another good year for the Journal of Finance. We received 1,300 submissions, of which 1,162 were new manuscripts. The number of new submissions rose by 11% from 2010. Resubmissions in- creased from 123 in 2010 to 138 in 2011. Note that in 2009 the Journal of Finance stopped counting “style” revisions in the official revision count, which accounts for the sharp drop in resubmissions after 2008. In 2011, the Journal published 60 articles, written by authors whose pri- mary affiliations include 75 different institutions. Table I details the number and timing of submissions received throughout the year. The primary affili- ations are summarized in Table II, which reports the number of authors per institution (where an article with n authors is counted as 1/n articles for each author’s institution). The institutions with the most Journal authors last year were the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, New York University, and the University of Chicago. The Journal’s visibility and impact remain extremely high. Table III shows that articles published in the Journal were cited 17,621 times in all journals during 2010, a total that ranks first among business and finance journals and third among all economics journals (behind the American Economic Review and Econometrica). Our 1-year impact factor (cites during 2010 to articles published in 2008 and 2009, divided by the total number of articles published in those 2 years) is 4.15 (up from 3.76 in 2009), which ranks second among business and finance journals and fifth among all economics journals (up from seventh in 2009). -

Michael Ryan Roberts

Michael Ryan Roberts Address: The Wharton School Citizenship: U.S. University of Pennsylvania 3620 Locust Walk, #2319 Philadelphia, PA 19104 Phone: (215) 573-9780 Fax: (215) 898-6200 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://finance.wharton.upenn.edu/~mrrobert March 2019 EDUCATION Degrees Attained Ph.D. in Economics, University of California, Berkeley, 2001 M.A. in Statistics, University of California, Berkeley, 2001 B.A. in Economics, University of California, San Diego, 1992 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Current Positions William H. Lawrence Professor, Professor of Finance, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 2013-Present Associate Faculty, Institute for Law and Economics, University of Pennsylvania, 2010 – Present Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010 – Present Researcher, Wharton Financial Institutions Center, University of Pennsylvania, 2010 – Present Previous Positions Visiting Scholar, London Business School, March 2014 Professor, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 2012 – 2013 Visiting Scholar, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University, 2012 – 2013 Associate Professor (with tenure), The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 2008 – 2012 Assistant Professor, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 2004 – 2008 Visiting Scholar, University of Vienna, Spring 2007 Assistant Professor, Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, 2001 – 2004 Lecturer, Department of Statistics, University of California at Berkeley, 1999 – 2001 Teaching Assistant, Department of Economics, University of California at Berkeley, 2000 – 2001 Teaching Assistant, Department of Statistics, University of California at Berkeley, 1996 – 1998 Research Assistant, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1996 – 1997 Teaching Assistant, Department of Economics, University of California at San Diego, 1992 RESEARCH (Authors in Alphabetical Order) Refereed Publications: Linnainmaa, Juhani and Michael R. Roberts, 2017, The History of the Cross Section of Stock Returns, forthcoming Review of Financial Studies • Geewax, Terker, and Co. -

Suntrust Beach Virtual Conference

12th Annual Florida State University SUNTRUST BEACH VIRTUAL CONFERENCE March 25-26, 2021 12th Annual FSU SunTrust Beach Virtual Conference March 25–26, 2021 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Note: All times are Eastern Time (ET) Note: Names in bold are the presenting authors and discussants THURSDAY, MARCH 25 9:00 am Opening Remarks 9:05 – 9:55 am How Financial Markets Create Superstars Spyros Terovitis – University of Amsterdam Vladimir Vladimirov – University of Amsterdam and CEPR Discussant: Nadya Malenko – University of Michigan 9:55 – 10:45 am Dirty Money: How Banks Influence Financial Crime Janet Gao – Indiana University Joseph Pacelli – Indiana University Jan Schneemeier – Indiana University Yufeng Wu – University of Illinois Discussant: Taylor A. Begley – Washington University in St. Louis 10:45 – 11:15 am Break 11:15 am – 12:05 pm SPACs Minmo Gahng – University of Florida Jay R. Ritter – University of Florida Donghang Zhang – University of South Carolina Discussant: Michelle Lowry – Drexel University 12:05 – 1:30 pm Lunch Break 1:30 – 2:20 pm Momentum, Reversals, and Investor Clientele Andy C.W. Chui – The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Avanidhar Subrahmanyam – University of California at Los Angeles Sheridan Titman – University of Texas at Austin and NBER Discussant: Zhi Da – University of Notre Dame 2:20 – 3:10 pm Attention Induced Trading and Returns: Evidence from Robinhood Users Brad M. Barber – UC Davis Xing Huang – Washington University in St. Louis Terrance Odean – University of California, Berkeley Chris Schwarz – UC Irvine Discussant: Azi Ben-Rephael – Rutgers University 3:10 – 3:30 pm Break 3:30 – 4:20 pm Too Many Managers: Strategic Use of Titles to Avoid Overtime Payments Lauren Cohen – Harvard and NBER Umit. -

ANTHONY W. LYNCH New York University 44 W 4Th Street #9-190 New York NY 10012 USA Phone: (212) 998-0350 Email: [email protected]

11/15/15 ANTHONY W. LYNCH New York University 44 W 4th Street #9-190 New York NY 10012 USA Phone: (212) 998-0350 Email: [email protected] Current Academic Position Professor of Finance, Stern School of Business, New York University, 2012-present . Associate Professor of Finance, Stern School of Business, New York University, 2001- 2012. Assistant Professor of Finance, Stern School of Business, New York University, 1994-2001. Academic Affiliations Research Associate, NBER, 2002 to present. Education Ph.D. (Finance and Economics), University of Chicago, 1994. Bachelor of Law with Honors, University of Queensland, 1989. Masters of Financial Management, University of Queensland, 1988. Bachelor of Commerce with First Class Honors, University of Queensland, 1986. Research Interests Frictions and decision-making; Multiple risky assets, return predictability and decision- making; Equilibrium pricing with cash flow predictability and frictions; Mutual funds; Survivorship and attrition biases; Using economic theory to understand firm and individual behavior; Financial econometric theory. Citations As of 2/25/15, my published papers have been cited 522 times by published papers using ISI Web of Knowledge’s Search function. Refereed Publications All published and working papers can be downloaded from my website: http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~alynch/ 15. Lynch, A. W., and Wachter, J., 2013. Using Samples of Unequal Length in Generalized Method of Moments Estimation. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 48, 277-307. 14. Lynch, A. W. and Tan, S., 2011. Explaining the Magnitude of Liquidity Premia: The Roles of Return Predictability, Wealth Shocks and State-dependent Transaction Costs. Journal of Finance 66, 1329-1368. -

Report of the Editor of the Journal of Finance for the Year 2008

THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE • VOL. LXIV, NO. 4 • AUGUST 2009 AMERICAN FINANCE ASSOCIATION Report of the Editor of The Journal of Finance for the Year 2008 CAMPBELL R. HARVEY, EDITOR I AM HAPPY TO REPORT that 2008 was another good year for The Journal of Finance. We received 1,191 submissions, of which 1,020 were new manuscripts, which is down slightly from last year. In 2008, the Journal published 80 articles, written by authors whose primary affiliations include 94 different institutions. Table I details the number and timing of submissions received throughout the year. The primary affiliations are summarized in Table II, which reports the number of authors per institution (where an article with n authors is counted as 1/n articles for each author’s institution). The institutions with the most JF authors last year were Columbia University, Duke University,1 and Harvard University. The Journal ’s visibility and impact remain extremely high. The articles pub- lished in the Journal in 2005 and 2006 were cited 10,473 times during 2007, a total that ranks first among business and finance journals and fourth among all economics journals (behind the American Economic Review, Econometrica, and the Journal of Political Economy). Our impact factor (cites during 2007 to articles published in 2005 and 2006, divided by the total number of articles pub- lished in those 2 years) is 3.353, which ranks first among business and finance journals and fourth among all economics journals. Turnaround time remains good, with almost 70% of the editorial decisions taking less than 60 days and only about 14% taking over 100 days. -

Speaker Bios

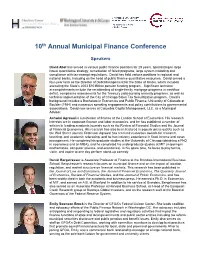

10th Annual Municipal Finance Conference Speakers David Abel has served in various public finance positions for 29 years, specializing in large issuer quantitative strategy, remediation of failed programs, large system modeling and compliance with tax-exempt regulations. David has held various positions in regional and national banks, including as the head of public finance quantitative resources. David served a four-year term as the Director of Debt Management for the State of Illinois, which included executing the State’s 2003 $10 Billion pension funding program. Significant technical accomplishments include the recalibrating of single-family mortgage programs in cashflow deficit, compliance assessments for the Treasury yield-burning amnesty programs, as well as technical implementation of the City of Chicago Sales Tax Securitization program. David’s background includes a Bachelors in Economics and Public Finance; University of Colorado at Boulder (1984) and numerous speaking engagements and policy contributions to governmental associations. David now serves at Columbia Capital Management, LLC, as a Municipal Advisor. Ashwini Agrawal is a professor of finance at the London School of Economics. His research interests are in corporate finance and labor economics, and he has published a number of articles in leading academic journals such as the Review of Financial Studies and the Journal of Financial Economics. His research has also been featured in popular press outlets such as the Wall Street Journal. Professor Agrawal has received numerous awards for research, teaching, and academic refereeing, and he has industry experience in fixed income and asset management. He completed his graduate studies at the University of Chicago (obtaining a PhD in economics and an MBA), and he completed his undergraduate studies at MIT (majoring in mathematics, computer science, and economics). -

List of ABDC Journals

List of ABDC Journals Current as of: 23/04/2018 19:58:58 Journal Title Publisher ABDC Rating 4OR: Quarterly Journal of Operations Research Springer International Publishing B A St A - Advances in Statistical Analysis Springer International Publishing C AACE International Transactions AACE International B Abacus: a journal of accounting, finance and business John Wiley & Sons, Inc. A studies Academia Economic Papers American Economic Association C Academy of Management Annals Taylor & Francis Online A* Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal Academy of Accounting and Financial C Studies Academy of Management Discoveries Academy of Management A Academy of Management Journal Academy of Management A* Academy of Management Learning and Education Academy of Management A* Academy of Management Perspectives Academy of Management A Academy of Management Review Academy of Management A* Academy of Marketing Science Review Academy of Marketing Science B Academy of Marketing Studies Journal Allied Academies C Accident Analysis and Prevention Elsevier A* Accountancy Business and the Public Interest Association for Accountancy & Business C Affairs Accounting Accountability and Performance Griffith University C Accounting and Business Research Taylor & Francis Online A Accounting and Finance John Wiley & Sons, Inc. A Accounting and Finance Research Sciedu Press C Accounting and Taxation The University of the South Pacific C Accounting and the Public Interest American Accounting Association B Accounting Auditing and Accountability Journal