PUBLIC MEDIA and POLITICAL INDEPENDENCE: Lessons for the Future of Journalism from Around the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 April 6, 2020 DA 20-385 Jessica J. González Gaurav Laroia Free Press 1025 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 1110 Washington, D.C. 20036 Re: Free Press Emergency Petition for Inquiry Into Broadcast of False Information on COVID-19 Dear Counsel: Free Press has filed, under section 1.41 of the Federal Communications Commission’s rules,1 an emergency petition requesting an investigation into broadcasters that have aired the President of the United States’ statements and press conferences regarding the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and related commentary by other on-air personalities. The Petition claims that the President and various commentators have made false statements regarding COVID-19, which Commission licensees have broadcast to the public, and which allegedly have caused or will cause substantial public harm.2 Free Press asks the Commission, under its section 309 public interest authority3 and its rules prohibiting broadcast hoaxes,4 to investigate these broadcasts and adopt emergency enforcement guidance “recommending that broadcasters prominently disclose when information they air is false or scientifically suspect.”5 We deny Free Press’s petition. For the reasons explained below, the Petition misconstrues the Commission’s rules and seeks remedies that would dangerously curtail the freedom of the press embodied in the First Amendment. Free Press, an organization purportedly dedicated to empowering diverse journalistic voices, demands the Commission impose significant burdens on broadcasters that are attempting to cover a rapidly evolving international pandemic in real time and punish those that, in its view, have been insufficiently critical of statements made by the President and others. -

Reporting Facts: Free from Fear Or Favour

Reporting Facts: Free from Fear or Favour PREVIEW OF IN FOCUS REPORT ON WORLD TRENDS IN FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND MEDIA DEVELOPMENT INDEPENDENT MEDIA PLAY AN ESSENTIAL ROLE IN SOCIETIES. They make a vital contribution to achieving sustainable development – including, topically, Sustainable Development Goal 3 that calls for healthy lives and promoting well-being for all. In the context of COVID-19, this is more important than ever. Journalists need editorial independence in order to be professional, ethical and serve the public interest. But today, journalism is under increased threat as a result of public and private sector influence that endangers editorial independence. All over the world, journalists are struggling to stave off pressures and attacks from both external actors and decision-making systems or individuals in their own outlets. By far, the greatest menace to editorial independence in a growing number of countries across the world is media capture, a form of media control that is achieved through systematic steps by governments and powerful interest groups. This capture is through taking over and abusing: • regulatory mechanisms governing the media, • state-owned or state-controlled media operations, • public funds used to finance journalism, and • ownership of privately held news outlets. Such overpowering control of media leads to a shrinking of journalistic autonomy and contaminates the integrity of the news that is available to the public. However, there is push-back, and even more can be done to support editorial independence -

Mediamonitor – Mediabedrijven En Mediamarkten 2001-2010

mediamonitor MEDIABEDRIJVEN EN MEDIAMARKTEN 2001-2010 © september 2011 Commissariaat voor de Media Colofon De Mediamonitor is een uitgave van het Commissariaat voor de Media Redactie Marcel Betzel Miriam van der Burg Edmund Lauf Rini Negenborn Jan Vosselman Bosch Vormgeving Studio FC Klap Druk Roto Smeets GrafiServices Commissariaat voor de Media Hoge Naarderweg 78 lllll 1217 AH Hilversum Postbus 1426 lllll 1200 BK Hilversum T 035 773 77 00 lllll F 035 773 77 99 lllll [email protected] lllll www.cvdm.nl lllll www.mediamonitor.nl ISSN 2211-2995 inhoud Voorwoord 5 Samenvatting 7 1. Trends en ontwikkelingen 15 1.1 Actuele ontwikkelingen 16 1.2 Eerder gesignaleerde trends 21 2. Mediabedrijven 25 2.1 Een terugblik 26 2.2 Financiële kengetallen 2001-2010 34 2.3 Mediabedrijven in 2010 37 3. Mediamarkten 59 3.1 Dagbladen 61 3.2 Publiekstijdschriften 70 3.3 Televisie 79 3.4 Radio 86 3.5 Internet 93 Methodische verantwoording 99 voorwoord De Adviescommissie Mediaconcentraties kwam twaalf jaar geleden tot de conclusie dat in een dynamische markt als de mediasector het voortdurend nauwgezet volgen van mediaontwikkelingen door een onafhankelijke instantie noodzakelijk is. Volgens de commissie moet het doel van de monitoring zijn om vroegtijdig ontwikkelingen te onderkennen die de pluriformiteit en onafhankelijkheid van informatievoorziening kunnen bedreigen. Het ministerie van OCW heeft het Commissariaat voor de Media in 2001 met deze taak belast en heeft daarbij twee speerpunten opgesteld. Zo worden jaarlijks de ontwikkelingen op de gebruikersmarkten voor dagbladen, tijdschriften, radio, televisie en internet en de bijbehorende grote spelers gevolgd. Daarnaast is er een focus op de nieuws- en opiniefunctie. -

Market Structure and Media Diversity Scott J. Savage, Donald M

Market Structure and Media Diversity1 Scott J. Savage, Donald M. Waldman, Scott Hiller University of Colorado at Boulder Department of Economics Campus Box 256 Boulder, CO 80309-0256 Abstract We estimate the demand for local news service described by the offerings from newspapers, radio, television, the Internet, and Smartphone. The results show that the representative consumer values diversity in the reporting of news, more coverage of multicultural issues, and more information on community news. About two-thirds of consumers have a distaste for advertising, which likely reflects their consumption of general, all-purpose advertising delivered by traditional media. Demand estimates are used to calculate the impact on consumer welfare from a marginal decrease in the number of independent television stations that lowers the amount of diversity, multiculturalism, community news, and advertising in the market. Welfare decreases, but the losses are smaller in large markets. For example, small-market consumers lose $53 million annually while large-market consumers lose $15 million. If the change in market structure occurs in all markets, total losses nationwide would be about $830 million. September 25, 2012 Key words: market structure, media diversity, mixed logit, news, welfare JEL Classification Number: C9, C25, L13, L82, L96 1 The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Time Warner Cable (TWC) Research Program on Digital Communications provided funding for this research. We are grateful to Jessica Almond, Fernando Laguarda, Jonathan Levy, and Tracy Waldon for their assistance during the completion of this project. Yongmin Chen, Nicholas Flores, Jin-Hyuk Kim, David Layton, Edward Morey, Gregory Rosston, Bradley Wimmer, and seminar participants at the University of California, University of Colorado, SUNY and attendees at the Conference in Honor of Professor Emeritus Lester D. -

What Women Want RTL Nederland’S New Special-Interest Channel

24 September 2009 week 39 What women want RTL Nederland’s new special-interest channel Luxembourg United States The value of TV advertising Kevin Skinner wins America’s Got Talent Germany Russia Online commercial breaks Ren TV presents accepted new season COVER: Montage with different formats of RTL Lounge hat women want derland’s new special-interest channel 2 week 39 the RTL Group intranet Drama and Lifestyle A new digital special-interest channel is going on air just in time for RTL Nederland’s 20th anniversary on 2 October: RTL Lounge. Backstage spoke with Nicolas Eglau who spearheaded the project. The Netherlands - 24 September 2009 The Netherlands has traditionally been a very cable-dominated country. However, due to the low penetration of digital homes in the past, it has been relatively unattractive so far for commercial TV groups to launch their own special-interest channels. The significant increase in digital households over the past two years has changed the situation, so RTL Nederland has now come to an agreement with the two biggest cable operators in the country – UPC and Ziggo – to run RTL Lounge. The new channel goes on air on 2 October as part of the “Royaal” package for UPC subscribers and in Ziggo’s Film & Entertainment package for its customers. In this way, RTL Lounge will reach 15 to 20 per cent of Dutch households in future. At the RTL Nederland programme presentation on 24 August, RTL Nederland CEO Bert Habets said: “RTL is tracking viewers on all platforms. Digital television is becoming increasingly more Nicolas Eglau important. -

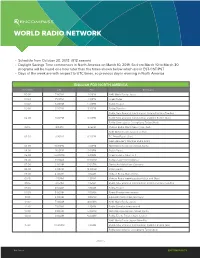

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

“Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4239–4257 1932–8036/20160005 Doing “Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News DEBING FENG1 Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China Unlike print news that is static and mainly composed of written text, television news is dynamic and needs to be delivered with diversified presentational modes and forms. Drawing upon Bakhtin’s heteroglossia and Goffman’s production format of talk, this article examined the presentational forms and strategies deployed in BBC News at Ten and CCTV’s News Simulcast. It showed that the employment of different presentational elements and forms in the two programs reflects two contrasting types of news discourse. The discourse of BBC News tends to present different, and even confrontational, voices with diversified presentational forms, such as direct mode of address and “fresh talk,” thus likely to accentuate the authenticity of the news. The other type of discourse (i.e., CCTV News) seems to prefer monologic news presentation and prioritize studio-based, scripted news reading, such as on-camera address or voice- overs, and it thus creates a single authoritative voice that is likely to undermine the truth of the news. Keywords: authenticity, mode of address, presentational elements, voice, television news The discourse of television news has been widely studied within the linguistic world. Early in the 1970s, researchers in the field of critical linguistics (CL; e.g., Fowler, 1991; Fowler, Hodge, Kress, & Trew, 1979; Hodge & Kress, 1993) paid great attention to the ideological meaning of news by drawing upon a kit of linguistic tools such as modality, transitivity, and transformation. -

Schumacher, Frederike Die Causa Brender

Fachbereich Medien Schumacher, Frederike Die Causa Brender - Einschränkungen der Rundfunkfreiheit im ZDF- Staatsvertrag durch Zusammensetzung und Befugnisse des Verwaltungsrats. - Bachelorarbeit - Hochschule Mittweida (FH) – University of Applied Sciences Hamburg - 2010 Fachbereich Medien Schumacher, Frederike Die Causa Brender - Einschränkungen der Rundfunkfreiheit im ZDF- Staatsvertrag durch Zusammensetzung und Befugnisse des Verwaltungsrats. The Causa Brender Limitations of freedom of boadcasting in the ZDF-Staatsvertrag* due to constitution and power of the administrative board. * ZDF-treaty: a legal framework for the german public broadcasting service ZDF. - eingereicht als Bachelorarbeit- Hochschule Mittweida (FH) – University of Applied Sciences Erstprüfer Zweitprüfer Prof. Dr. phil Otto Altendorfer Heidrun Köhlert Hamburg- 2010 Schumacher, Frederike: Die Causa Brender - Einschränkungen der Rundfunkfreiheit im ZDF-Staats- vertrag durch Zusammensetzung und Befugnisse des Verwaltungsrats. – 2010- 79 S. Mittweida, Hochschule (FH), Fachbereich Medien, Bachelorarbeit Referat Diese Bachelorarbeit beschäftigt sich mit der Übersetzung des Begriffs der Rund- funkfreiheit im ZDF-Staatsvertrag. Sie untersucht, ob die Grundsätze dieser Rundfunkfreiheit, wie sie durch das Ver- fassungsgericht in seinen Fernsehurteilen und darüber hinaus definiert wurden, hierin ausreichend berücksichtigt werden, und sie zeigt wo die Rundfunkfreiheit Einschränkungen erfährt. Anstoß zu der Fragestellung gaben die Entwicklungen und Entscheidungen, die der Abwahl -

In the Service of the Public Functions and Transformation of Media in Developing Countries Imprint Publisher Deutsche Welle 53110 Bonn, Germany

Edition dW AkAdEmiE #02/2014 mEdiA dEvElopmEnt In the Service of the Public Functions and Transformation of Media in Developing Countries Imprint pUBliSHER Deutsche Welle 53110 Bonn, Germany RESponSiBlE Christian Gramsch AUtHoRS Erik Albrecht Cletus Gregor Barié Petra Berner Priya Esselborn Richard Fuchs Lina Hartwieg Jan Lublinski Laura Schneider Achim Toennes Merjam Wakili Jackie Wilson-Bakare EditoRS Jan Lublinski Merjam Wakili Petra Berner dESiGn Programming / Design pRintEd November 2014 © DW Akademie Edition dW AkAdEmiE #02/2014 mEdiA dEvElopmEnt In the Service of the Public Functions and Transformation of Media in Developing Countries Jan Lublinski, Merjam Wakili, Petra Berner (eds.) Table of Contents Preface 4 04 Kyrgyzstan: Advancements in Executive Summary 6 a Media-Friendly Environment 52 Jackie Wilson-Bakare Part I: Developing Public Service Media – Kyrgyzstan – A Brief Overview 53 Functions and Change Processes Media Landscape 54 Obschestvennaya Tele-Radio Kompaniya (OTRK) 55 01 Introduction: A Major Challenge for Stakeholders in the Transformation Process 56 Media Development 10 Status of the Media Organization 56 Jan Lublinski, Merjam Wakili, Petra Berner Public Service: General Functions 61 Public Service Broadcasting – West European Roots, Achievements and Challenges 62 International Ambitions 12 Transformation Approaches 63 Lessons Learned? – Transformations Since the 1990s 14 Appendix 72 Reconsidering Audiences – Media in the Information Society 15 05 Namibia: Multilingual Content and the Need Approach and Aim of the -

Record of Agreement

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 26.1.2010 C(2010)132 final In the published version of this decision, some information PUBLIC VERSION has been omitted, pursuant to articles 24 and 25 of Council Regulation (EC) No 659/1999 of 22 March 1999 laying WORKING LANGUAGE down detailed rules for the application of Article 93 of the EC Treaty, concerning non-disclosure of information This document is made available for covered by professional secrecy. The omissions are information purposes only. shown thus […]. Subject: State aid E 5/2005 (ex NN 170b/2003) – Annual financing of the Dutch public service broadcasters – The Netherlands Excellency, The Commission has the honour to inform you that the commitments given by the Netherlands in the context of the present procedure remove the Commission's concerns about the incompatibility of the current annual financing regime. Consequently, the Commission decided to close the present investigation. 1. PROCEDURE (1) The present case was initiated based on a number of complaints. (2) On 24 May 2002 the Commission received a complaint from CLT-UFA S.A. and its associated subsidiaries RTL/de Holland Media Groep S.A. and Yorin tv BV regarding the financing of Dutch public broadcasters. On 10 October 2002 and 28 November 2002 SBS Broadcasting and VESTRA1, the association of commercial broadcasters in the Netherlands, each submitted complaints. VESTRA also submitted further information in the course of the investigation. On 3 June 2003 NDP, the Dutch Newspaper Publishers Association, submitted a complaint on behalf of its members. On 19 June 2003 the publishing company De Telegraaf lodged a complaint. -

Review of Content Regulation Models

Issues facing broadcast content regulation MILLWOOD HARGRAVE LTD. Authors: Andrea Millwood Hargrave, Geoff Lealand, Paul Norris, Andrew Stirling Disclaimer The report is based on collaborative desk research conducted for the New Zealand Broadcasting Standards Authority over a two month period. Issue date November 2006 © Broadcasting Standards Authority, New Zealand Contents Aim and Scope of this Report..................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary.................................................................................................... 4 A: Introduction............................................................................................................. 6 Background............................................................................................................. 6 Definitions............................................................................................................... 9 What is the justification for regulation?.................................................................... 9 Protective content regulation: an overview............................................................ 10 Proactive content regulation: an overview............................................................. 12 Co-regulation and self-regulation........................................................................... 12 Technological changes and convergence.............................................................. 15 Differences in devices.......................................................................................... -

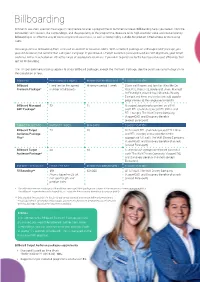

Billboarding Billboards Are Short Sponsor Messages (5 Sec) Before Or After a Programme Or Commercial Break

Billboarding Billboards are short sponsor messages (5 sec) before or after a programme or commercial break. Billboarding helps you benefit from the connection with viewers, the surroundings, and the popularity of the programme. Because of its high attention value and cost-efficiency, billboarding is an effective way of increasing brand awareness, as well as being highly suitable for product introductions or increasing sales. You can purchase billboarding from us based on content or based on GRPs. With a Content package or a Managed GRP package, you yourself decide on the content that suits your campaign. If you choose a Target Audience package based on GRP objectives, your target audience will be reached on an attractive range of appropriate channels. If you wish to purchase to the best-possible cost-efficiency, then opt for Fill boarding. The TV spot commercial policy applies to all our Billboard packages, except the Premium Package. See the purchase system diagram for the calculation of fees. CONTENT FEE/PRODUCT INDEX MINIMUM PERIOD/GRPS CLASSIFICATION Billboard Fixed fee for the agreed Minimum period 1 week Claim well-known and familiar titles like De Premium Package* number of billboards Klok, RTL Weer, RTL Boulevard, Jinek, Married At First Sight, Weet Ik Veel, Chantals Beauty Camper and films and series (we add popular programmes to the range every month) Billboard Managed 83 15 Managed according to content on all full GRP Package* audit RTL channels (except RTL Crime and RTL Lounge), The Walt Disney Company, ViacomCBS, and Discovery Benelux (except Eurosport). TARGET AUDIENCE PRODUCT INDEX MIN GRPS CLASSIFICATION Billboard Target 78 10 All full audit RTL channels (except RTL Crime Audience Package and RTL Lounge) and a selection of the Plus* appropriate full audit The Walt Disney Company, ViacomCBS, and Discovery Benelux channels (except Eurosport).