Segregation and Environmental Policies in Miami from the New Deal to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARNOLD MITTELMAN Producer/Director 799 Crandon

ARNOLD MITTELMAN Producer/Director 799 Crandon Boulevard, #505 Key Biscayne, FL 33149 [email protected] ARNOLD MITTELMAN is a producer and director with 40 years of theatrical achievement that has resulted in the creation and production of more than 300 artistically diverse plays, musicals and special events. Prior to coming to the world famous Coconut Grove Playhouse in 1985, Mr. Mittelman directed and produced Alone Together at Broadway's Music Box Theatre. Succeeding the esteemed actor José Ferrer as the Producing Artistic Director of Coconut Grove Playhouse, he continued to bring national and international focus to this renowned theater. Mr. Mittelman helped create more than 200 plays, musicals, educational and special events on two stages during his 21-year tenure at the Playhouse. These plays and musicals were highlighted by 28 World or American premieres. This body of work includes three Pulitzer Prize-winning playwrights directing their own work for the first time in a major theatrical production: Edward Albee - Seascape; David Auburn - Proof; and Nilo Cruz - Anna In the Tropics. Musical legends Cy Coleman, Charles Strouse, Jerry Herman, Jimmy Buffett, John Kander and Fred Ebb were in residence at the Playhouse to develop world premiere productions. The Coconut Grove Playhouse has also been honored by the participation of librettist/writers Herman Wouk, Alfred Uhry, Jerome Weidman and Terrence McNally. Too numerous to mention are the world famous stars and Tony award-winning directors, designers and choreographers who have worked with Mr. Mittelman. Forty Playhouse productions, featuring some of the industry's greatest theatrical talents and innovative partnerships between the not-for-profit and for-profit sectors, have transferred directly to Broadway, off-Broadway, toured, or gone on to other national and international venues (see below). -

Smartdraw Document

Theatres at which ACA graduates have worked since graduation: Broadway, King Lear with Christopher Plummer Broadway, Merchant of Venice with Al Pacino 1st National Broadway Tour: August: Osage County 1st National Broadway Tour: The Graduate 1st National Broadway Tour: Spamalot National Tour: The SantaLand Diaries 34 West Theatre Company (NYC) 59E59 Theater (NYC) Acting Company Actor's Express Actors Shakespeare Company at New Jersey City University Actors Shakespeare Project Actors Theatre of Louisville* Actors Theatre of Minnesota Arden Theatre Adrienne Alabama Shakespeare Festival Alliance Theatre* American Century Theater American Globe Theatre American Players Theatre, Wisconsin American Repertory Theater* American Shakespeare Center American Theater Company A Noise Within Antaeus Theatre Company Arena Stage* Artists Repertory Theatre Arts Alive Theatre Arts Center of Coastal Carolina Arts United DC ArtsWest Arvada Center Atlas Performing Arts Attic Theatre and Film Center, L.A. Austin Playhouse Austin Shakespeare Baltimore Shakespeare Festival Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Barnstormers Barrington Stage (Berkshires) Bay Theatre, Annapolis Beckett Theatre, Theatre Row Berkeley Repertory Theatre* You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Black Repertory Company of St. Louis Blue Herron Theatre, NYC Boston Playwrights' Theater Boston Theatre Works Breaking String Theatre Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Outdoor Arts Festival Bunbury Theatre Cadence Theatre Company -

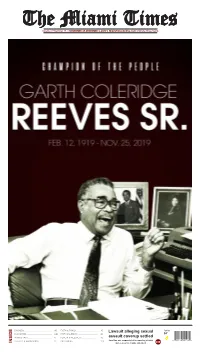

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR. -

A Brief History of Lake Okeechobee: a Narrative of Confict Alanna L

A Brief History of Lake Okeechobee: A Narrative of Confict Alanna L. Lecher, Ph.D, Lynn University Abstract Lake Okeechobee is Florida’s largest lake, the largest lake in the Southeast United States, and the second largest lake contained entirely within the United States. The history of this inland sea is marked both by natural processes, and more recently human development and intervention. Adventurers can explore this behemoth of a waterway via the Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail that enriches it, a part of the Florida National Scenic Trail. This paper synthesizes major natural and human-induced perturbations that shaped the lake and ultimately the trail that encircles it to create a narrative of Florida’s great lake. The story of Lake Okeechobee is a story of battles, frst between the land and sea, then between the lake itself and humankind. For the past few centuries Lake Okeechobee’s natural perturbations in water fow and fooding resisted the control of man, until recently when man triumphed, managing to control the fow of water in and out of the lake. Unfortunately, with this new found control a new bio- ecological threat in the form of harmful algal blooms has emerged, which again threatens the health and livelihood of South Floridians. Currently there are new eforts that seek to restore Lake Okeechobee towards a more natural state in an efort to thwart the blooms. Manuscript It’s a full moon weekend in February and runners lace up their shoes in preparation. They gather in the agricultural town of Clewiston southeast of Lake Okeechobee. -

Ethnic Community, Party Politics, and the Cold War: the Political Ascendancy of Miami Cubans, 1980–2000

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 23 (2012) Ethnic Community, Party Politics, and the Cold War: The Political Ascendancy of Miami Cubans, 1980–2000 Hideaki KAMI* INTRODUCTION Analysis of the implications of the rapidly growing Latino/Hispanic electorate for future U.S. political life is a relatively new project for his- torians and political scientists.1 Indeed, the literature on Latino politics has long considered their political underrepresentation as the central issue for research. Many scholars in the field have sought to explain how the burden of historical discrimination and antagonistic attitudes toward immigrants has discouraged these minorities from taking part in U.S. politics. Their studies have also explored how to overcome low voter turnout among Latinos and detect unfavorable institutional obstacles for voicing their opinions in government.2 However, partly due to previous academic efforts, the 1990s and 2000s have witnessed U.S. voters of Hispanic origin solidifying their role as a key constituency in U.S. pol- itics. An increasing number of politicians of Hispanic origin now hold elective offices at local, state, and national levels. Both the Republican and Democratic Parties have made intensive outreach efforts to seize the hearts and minds of these new voters, particularly by broadcasting spe- cific messages in Spanish media such as Univision.3 Although low *Graduate student, University of Tokyo and Ohio State University 185 186 HIDEAKI KAMI turnout among Latino voters and strong anti-immigrant sentiments among many non-Latino voters persist, the growing importance of the Latino electorate during the presidential elections has attracted increas- ing attention from inside and outside academic circles.4 Hence, in 2004, political scientist Rodolfo O. -

Introduction Black Miamians Are Experiencing Racial Inequities Including Climate Gentrification, Income Inequality, and Disproportionate Impacts of COVID-19

Introduction Black Miamians are experiencing racial inequities including climate gentrification, income inequality, and disproportionate impacts of COVID-19. Significant gaps in wealth also define the state of racial equity in Miami. Black Miamians have a median wealth of just $3,700 per household compared to $107,000 for white 2 households. These inequities reflect the consistent, patterned effects of structural racism and growing income and wealth inequalities in urban areas. Beyond pointing out the history and impacts of structural racism in Miami, this city profile highlights the efforts of community activists, grassroots organizations and city government to disrupt the legacy of unjust policies and decision-making. In this brief we also offer working principles for Black-centered urban racial equity. Though not intended to be a comprehensive source of information, this brief highlights key facts, figures and opportunities to advance racial equity in Miami. Last Updated 08/19/2020 1 CURE developed this brief as part of a series of city profiles on structural inequities in major cities. They were originally created as part of an internal process intended to ground ourselves in local history and current efforts to achieve racial justice in cities where our client partners are located. With heightened interest in these issues, CURE is releasing these briefs as resources for organizers, nonprofit organizations, city government officials and others who are coordinating efforts to reckon with the history of racism and anti-Blackness that continues to shape city planning, economic development, housing and policing strategies. Residents most impacted by these systems are already leading the change and leading the process of reimagining Miami as a place where Black Lives Matter. -

Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms

FLORIDA HURRICANES AND TROPICAL STORMS 1871-1995: An Historical Survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams '+wcCopy~~ I~BN 0-912747-08-0 Florida SeaGrant College is supported by award of the Office of Sea Grant, NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce,grant number NA 36RG-0070, under provisions of the NationalSea Grant College and Programs Act of 1966. This information is published by the Sea Grant Extension Program which functionsas a coinponentof the Florida Cooperative Extension Service, John T. Woeste, Dean, in conducting Cooperative Extensionwork in Agriculture, Home Economics, and Marine Sciences,State of Florida, U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, U.S. Departmentof Commerce, and Boards of County Commissioners, cooperating.Printed and distributed in furtherance af the Actsof Congressof May 8 andJune 14, 1914.The Florida Sea Grant Collegeis an Equal Opportunity-AffirmativeAction employer authorizedto provide research, educational information and other servicesonly to individuals and institutions that function without regardto race,color, sex, age,handicap or nationalorigin. Coverphoto: Hank Brandli & Rob Downey LOANCOPY ONLY Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms 1871-1995: An Historical survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams Division of Marine and Environmental Systems, Florida Institute of Technology Melbourne, FL 32901 Technical Paper - 71 June 1994 $5.00 Copies may be obtained from: Florida Sea Grant College Program University of Florida Building 803 P.O. Box 110409 Gainesville, FL 32611-0409 904-392-2801 II Our friend andcolleague, Fred Doehringpictured below, died on January 5, 1993, before this manuscript was completed. Until his death, Fred had spent the last 18 months painstakingly researchingdata for this book. -

Caplinfrdrysdale Washington

Caplin s Dryidalc. Chartered One Thomas Circle. NW. Suite 1100 CaplinfrDrysdale Washington. DC 20005 202-862-5000 202-429-3301 fax A T I I I I E ! S wMMr.caplindryidale.com May 3,2004 Renee Salzmann, Esq. Office of General Counsel Federal Election Commission "0 999 E Street, N.W. xr > 5 Washington, D.C. 20463 ro O Re: MUR 5379 (Michael B. Fernandez) Dear Ms. Salzmann: On behalf of Respondent Michael B. Fernandez, I am hereby providing you with an amended statement of Mr. Fernandez. With the exception of the first phrase of paragraph five, the attached statement is identical to the statement dated September 18, 2003 submitted by Mr. Fernandez in response to the complaint filed by Peter Deutsch for Senate. Thus, paragraph five had stated, "In early March of 2002," but has now been corrected to state, "In early 2003." Please do not hesitate to call me with any questions. Sincerely Enclosure DOC* 217937 vl - OS/03/2004 Statement of Michael B. Fernandez 1. My name is Michael Fernandez. I am providing this statement in response to the complaint filed by Peter Deutsch for Senate in MUR 5379 against Mayor Alex Penelas. 2. I am Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of CAC-CarePlus Health Plans, Inc. ("CarePlus"). I also am the Chairman & CEO of CPHP Holdings, Inc. 0> and Chairman of Healthcare Atlantic Corporation. I have been a healthcare ^p executive for the better part of the past three decades. O •-I 3. I have lived in Miami since 1975. It is my home. It is where I raise my ^ family, make my living, and participate in community events. -

106Th Congress 65

FLORIDA 106th Congress 65 Office Listings http://www.house.gov/foley [email protected] 113 Cannon House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 .................................... (202) 225±5792 Chief of Staff.ÐKirk Fordham. FAX: 225±3132 Press Secretary.ÐSean Spicer. Legislative Director.ÐElizabeth Nicolson. 4440 PGA Boulevard, Suite 406, Palm Beach Gardens, FL 33410 ........................... (561) 627±6192 District Manager.ÐEd Chase. FAX: 626±4749 County Annex Building, 250 Northwest Country Club Drive, Port St. Lucie, FL 34986 ......................................................................................................................... (561) 878±3181 District Manager.ÐAnn Decker. FAX: 871±0651 Counties: Glades, Hendry, Highlands, Martin, Okeechobee, Palm Beach, and St. Lucie. Population (1990), 562,519. ZIP Codes: 33401 (part), 33403 (part), 33404 (part), 33406 (part), 33407 (part), 33409 (part), 33410 (part), 33411 (part), 33412, 33413 (part), 33414 (part), 33415 (part), 33417±18, 33430 (part), 33437 (part), 33440 (part), 33455, 33458, 33461 (part), 33463 (part), 33467 (part), 33468±69, 33470 (part), 33471, 33475, 33477±78, 33498 (part), 33825 (part), 33852, 33857, 33870 (part), 33871±72, 33920 (part), 33930, 33935, 33944, 33960, 34945 (part), 34946 (part), 34947 (part), 34949, 34950 (part), 34951 (part), 34952±53, 34957±58, 34972 (part), 34973, 34974 (part), 34981 (part), 34982± 85, 34986 (part), 34987 (part), 34990, 34992, 34994±97 * * * SEVENTEENTH DISTRICT CARRIE P. MEEK, Democrat, of Miami, FL; born in Tallahassee, -

Oasis the Truth: My Life As Oasiss Drummer Free

FREE OASIS THE TRUTH: MY LIFE AS OASISS DRUMMER PDF Tony McCarroll | 288 pages | 01 May 2012 | John Blake Publishing Ltd | 9781843584995 | English | London, United Kingdom Oasis : The Truth: My Life as Oasis's Drummer - - Was not what it appeared to be. Was too small And paid way too much. Would not recommend to anyone. Here at Walmart. Your email address will never be sold or distributed to a third party for any reason. Sorry, but we can't respond to individual comments. If you need immediate assistance, please contact Customer Care. Your feedback helps us make Walmart shopping better for millions of customers. Recent searches Clear All. Enter Location. Update location. Learn more. Report incorrect product information. Tony McCarroll. Walmart Book Format. Select Option. Current selection is: Paperback. Free delivery Arrives by Wednesday, Nov 4. Pickup not available. Add to list. Add to registry. Here, Tony reveals the truth about the early years before the band was formed. He discusses the drug consumption, the sexual activities, his much-publicized rift with Oasis the Truth: My Life as Oasiss Drummer Gallagher, and how he was duped into signing a less-than-favorable record contract. Witty, revealing, and fascinating, this book is a Oasis the Truth: My Life as Oasiss Drummer for Oasis fans. About This Item. We aim to show you accurate product information. Manufacturers, suppliers and others provide what you see here, and we have not verified it. See our disclaimer. The candid and hilarious tale of the first five years of Oasis, from their founding drummer Tony McCarroll joined Oasis when they were still a band called The Rain. -

Historical Perspective

kZ _!% L , Ti Historical Perspective 2.1 Introduction CROSS REFERENCE Through the years, FEMA, other Federal agencies, State and For resources that augment local agencies, and other private groups have documented and the guidance and other evaluated the effects of coastal flood and wind events and the information in this Manual, performance of buildings located in coastal areas during those see the Residential Coastal Construction Web site events. These evaluations provide a historical perspective on the siting, design, and construction of buildings along the Atlantic, Pacific, Gulf of Mexico, and Great Lakes coasts. These studies provide a baseline against which the effects of later coastal flood events can be measured. Within this context, certain hurricanes, coastal storms, and other coastal flood events stand out as being especially important, either Hurricane categories reported because of the nature and extent of the damage they caused or in this Manual should be because of particular flaws they exposed in hazard identification, interpreted cautiously. Storm siting, design, construction, or maintenance practices. Many of categorization based on wind speed may differ from that these events—particularly those occurring since 1979—have been based on barometric pressure documented by FEMA in Flood Damage Assessment Reports, or storm surge. Also, storm Building Performance Assessment Team (BPAT) reports, and effects vary geographically— Mitigation Assessment Team (MAT) reports. These reports only the area near the point of summarize investigations that FEMA conducts shortly after landfall will experience effects associated with the reported major disasters. Drawing on the combined resources of a Federal, storm category. State, local, and private sector partnership, a team of investigators COASTAL CONSTRUCTION MANUAL 2-1 2 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE is tasked with evaluating the performance of buildings and related infrastructure in response to the effects of natural and man-made hazards. -

Ÿþa M E R I C a N R E N a I S S a N C E , O C T O B E R 2 0

American Renaissance There is not a truth existing which I fear or would wish unknown to the whole world. — Thomas Jefferson Vol. 16 No. 10 October 2005 Africa in Our Midst The media suppress Katri- day, Aug. 29. The levees broke on Tues- heads dispelled that view. day and the city began to flood. Before The day after the hurricane, a reporter na’s lessons. long, 80 percent of New Orleans was caught the atmosphere of high-spirited under as much as 20 feet of water. chaos at a Wal-Mart in the Lower Gar- by Jared Taylor The city’s 70,000-seat football sta- den District. People were grabbing dium, known as the Superdome, had things as quickly as they could, smash- n the aftermath of Hurricane ing open jewelry cabinets and Katrina, which blasted the scooping up double-handfuls. One IGulf Coast on Aug. 29, the man packed his van so full of elec- entire world saw images that left tronic equipment he could not no doubt that what is repeatedly close the rear doors. A teenage girl called the sole remaining super- passed out, face down, and people power can be reduced to squalor stepped on her. A man stopped to and chaos nearly as gruesome as roll her onto her back, and she anything found in the Third vomited pink liquid. “This is World. The weather—a Category f***ed up,” he said, and rolled her 4 hurricane—certainly had some- back on her stomach. An NBC cor- thing to do with it, but the most respondent filmed black, uni- serious damage was done not by formed police officers strolling nature but by man.