Starting Big – the Role of Multi-Word Phrases in Language Learning and Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Words: Is Lexicography for You? Lexicographers Decide Which Words Should Be Included in Dictionaries. They May Decide T

Creating Words: Is Lexicography for You? Lexicographers decide which words should be included in dictionaries. They may decide that a word is currently just a fad, and so they’ll wait to see whether it will become a permanent addition to the language. In the past several decades, words such as hippie and yuppie have survived being fads and are now found in regular, not just slang, dictionaries. Other words, such as medicare, were created to fill needs. And yet other words have come from trademark names, for example, escalator. Here are some writing options: 1. While you probably had to memorize vocabulary words throughout your school years, you undoubtedly also learned many other words and ways of speaking and writing without even noticing it. What factors are bringing about changes in the language you now speak and write? Classes? Songs? Friends? Have you ever influenced the language that someone else speaks? 2. How often do you use a dictionary or thesaurus? What helps you learn a new word and remember its meaning? 3. Practice being a lexicographer: Define a word that you know isn’t in the dictionary, or create a word or set of words that you think is needed. When is it appropriate to use this term? Please give some sample dialogue or describe a specific situation in which you would use the term. For inspiration, you can read the short article in the Writing Center by James Chiles about the term he has created "messismo"–a word for "true bachelor housekeeping." 4. Or take a general word such as "good" or "friend" and identify what it means in different contexts or the different categories contained within the word. -

Character-Word LSTM Language Models

Character-Word LSTM Language Models Lyan Verwimp Joris Pelemans Hugo Van hamme Patrick Wambacq ESAT – PSI, KU Leuven Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, 3001 Heverlee, Belgium [email protected] Abstract A first drawback is the fact that the parameters for infrequent words are typically less accurate because We present a Character-Word Long Short- the network requires a lot of training examples to Term Memory Language Model which optimize the parameters. The second and most both reduces the perplexity with respect important drawback addressed is the fact that the to a baseline word-level language model model does not make use of the internal structure and reduces the number of parameters of the words, given that they are encoded as one-hot of the model. Character information can vectors. For example, ‘felicity’ (great happiness) is reveal structural (dis)similarities between a relatively infrequent word (its frequency is much words and can even be used when a word lower compared to the frequency of ‘happiness’ is out-of-vocabulary, thus improving the according to Google Ngram Viewer (Michel et al., modeling of infrequent and unknown words. 2011)) and will probably be an out-of-vocabulary By concatenating word and character (OOV) word in many applications, but since there embeddings, we achieve up to 2.77% are many nouns also ending on ‘ity’ (ability, com- relative improvement on English compared plexity, creativity . ), knowledge of the surface to a baseline model with a similar amount of form of the word will help in determining that ‘felic- parameters and 4.57% on Dutch. Moreover, ity’ is a noun. -

Basic Morphology

What is Morphology? Mark Aronoff and Kirsten Fudeman MORPHOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 1 Thinking about Morphology and Morphological Analysis 1.1 What is Morphology? 1 1.2 Morphemes 2 1.3 Morphology in Action 4 1.3.1 Novel words and word play 4 1.3.2 Abstract morphological facts 6 1.4 Background and Beliefs 9 1.5 Introduction to Morphological Analysis 12 1.5.1 Two basic approaches: analysis and synthesis 12 1.5.2 Analytic principles 14 1.5.3 Sample problems with solutions 17 1.6 Summary 21 Introduction to Kujamaat Jóola 22 mor·phol·o·gy: a study of the structure or form of something Merriam-Webster Unabridged n 1.1 What is Morphology? The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‘shape, form’, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch 2 MORPHOLOGYMORPHOLOGY ANDAND MORPHOLOGICAL MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS ANALYSIS of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure, and how they are formed. n 1.2 Morphemes A major way in which morphologists investigate words, their internal structure, and how they are formed is through the identification and study of morphemes, often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with a gram- matical function. -

Learning About Phonology and Orthography

EFFECTIVE LITERACY PRACTICES MODULE REFERENCE GUIDE Learning About Phonology and Orthography Module Focus Learning about the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language (often referred to as letter-sound associations, graphophonics, sound- symbol relationships) Definitions phonology: study of speech sounds in a language orthography: study of the system of written language (spelling) continuous text: a complete text or substantive part of a complete text What Children Children need to learn to work out how their spoken language relates to messages in print. Have to Learn They need to learn (Clay, 2002, 2006, p. 112) • to hear sounds buried in words • to visually discriminate the symbols we use in print • to link single symbols and clusters of symbols with the sounds they represent • that there are many exceptions and alternatives in our English system of putting sounds into print Children also begin to work on relationships among things they already know, often long before the teacher attends to those relationships. For example, children discover that • it is more efficient to work with larger chunks • sometimes it is more efficient to work with relationships (like some word or word part I know) • often it is more efficient to use a vague sense of a rule How Children Writing Learn About • Building a known writing vocabulary Phonology and • Analyzing words by hearing and recording sounds in words Orthography • Using known words and word parts to solve new unknown words • Noticing and learning about exceptions in English orthography Reading • Building a known reading vocabulary • Using known words and word parts to get to unknown words • Taking words apart while reading Manipulating Words and Word Parts • Using magnetic letters to manipulate and explore words and word parts Key Points Through reading and writing continuous text, children learn about sound-symbol relation- for Teachers ships, they take on known reading and writing vocabularies, and they can use what they know about words to generate new learning. -

Linguistics 1A Morphology 2 Complex Words

Linguistics 1A Morphology 2 Complex words In the previous lecture we noted that words can be classified into different categories, such as verbs, nouns, adjectives, prepositions, determiners, and so on. We can make another distinction between word types as well, a distinction that cuts across these categories. Consider the verbs, nouns and adjectives in (1)-(3), respectively. It will probably be intuitively clear that the words in the (b) examples are complex in a way that the words in the (a) examples are not, and not just because the words in the (b) examples are, on the whole, longer. (1) a. to walk, to dance, to laugh, to kiss b. to purify, to enlarge, to industrialize, to head-hunt (2) a. house, corner, zebra b. collection, builder, sea horse (3) c. green, old, sick d. regional, washable, honey-sweet The words in the (a) examples in (1)-(3) do not have any internal structure. It does not seem to make much sense to say that walk , for example, consists of the smaller parts wa and lk . But for the words in the (b) examples this is different. These are built up from smaller parts that each contribute their own distinct bit of meaning to the whole. For example, builder consists of the verbal part build with its associated meaning, and the part –er that contributes a ‘doer’ reading, just as it does in kill-er , sell-er , doubt-er , and so on. Similarly, washable consists of wash and a part –able that contributes a meaning aspect that might be described loosely as ‘can be done’, as it does in refundable , testable , verifiable etc. -

Words Their Way®: Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development

Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Words Their Way®: Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Introduction In this tutorial, we will learn about the stages of spelling development included in the professional development book titled, Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 1 Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Three Layers of English Orthography There are three layers of orthography, or spelling, in the English language-the alphabet layer, the pattern layer, and the meaning layer. Students' understanding of the layers progresses through five predictable stages of spelling development. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 2 Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Alphabet Layer The alphabet layer represents a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. In this layer, students use the sounds of individual letters to accurately spell words. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 3 Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Pattern Layer The pattern layer overlays the alphabet layer, as there are 42 to 44 sounds in English but only 26 letters in the alphabet. In this layer, students explore combinations of sound spellings that form visual and auditory patterns. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. -

The Art of Lexicography - Niladri Sekhar Dash

LINGUISTICS - The Art of Lexicography - Niladri Sekhar Dash THE ART OF LEXICOGRAPHY Niladri Sekhar Dash Linguistic Research Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India Keywords: Lexicology, linguistics, grammar, encyclopedia, normative, reference, history, etymology, learner’s dictionary, electronic dictionary, planning, data collection, lexical extraction, lexical item, lexical selection, typology, headword, spelling, pronunciation, etymology, morphology, meaning, illustration, example, citation Contents 1. Introduction 2. Definition 3. The History of Lexicography 4. Lexicography and Allied Fields 4.1. Lexicology and Lexicography 4.2. Linguistics and Lexicography 4.3. Grammar and Lexicography 4.4. Encyclopedia and lexicography 5. Typological Classification of Dictionary 5.1. General Dictionary 5.2. Normative Dictionary 5.3. Referential or Descriptive Dictionary 5.4. Historical Dictionary 5.5. Etymological Dictionary 5.6. Dictionary of Loanwords 5.7. Encyclopedic Dictionary 5.8. Learner's Dictionary 5.9. Monolingual Dictionary 5.10. Special Dictionaries 6. Electronic Dictionary 7. Tasks for Dictionary Making 7.1. Panning 7.2. Data Collection 7.3. Extraction of lexical items 7.4. SelectionUNESCO of Lexical Items – EOLSS 7.5. Mode of Lexical Selection 8. Dictionary Making: General Dictionary 8.1. HeadwordsSAMPLE CHAPTERS 8.2. Spelling 8.3. Pronunciation 8.4. Etymology 8.5. Morphology and Grammar 8.6. Meaning 8.7. Illustrative Examples and Citations 9. Conclusion Acknowledgements ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) LINGUISTICS - The Art of Lexicography - Niladri Sekhar Dash Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The art of dictionary making is as old as the field of linguistics. People started to cultivate this field from the very early age of our civilization, probably seven to eight hundred years before the Christian era. -

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University In the Twentieth Century, Logic and Philosophy of Language are two of the few areas of philosophy in which philosophers made indisputable progress. For example, even now many of the foremost living ethicists present their theories as somewhat more explicit versions of the ideas of Kant, Mill, or Aristotle. In contrast, it would be patently absurd for a contemporary philosopher of language or logician to think of herself as working in the shadow of any figure who died before the Twentieth Century began. Advances in these disciplines make even the most unaccomplished of its practitioners vastly more sophisticated than Kant. There were previous periods in which the problems of language and logic were studied extensively (e.g. the medieval period). But from the perspective of the progress made in the last 120 years, previous work is at most a source of interesting data or occasional insight. All systematic theorizing about content that meets contemporary standards of rigor has been done subsequently. The advances Philosophy of Language has made in the Twentieth Century are of course the result of the remarkable progress made in logic. Few other philosophical disciplines gained as much from the developments in logic as the Philosophy of Language. In the course of presenting the first formal system in the Begriffsscrift , Gottlob Frege developed a formal language. Subsequently, logicians provided rigorous semantics for formal languages, in order to define truth in a model, and thereby characterize logical consequence. Such rigor was required in order to enable logicians to carry out semantic proofs about formal systems in a formal system, thereby providing semantics with the same benefits as increased formalization had provided for other branches of mathematics. -

4. the History of Linguistics : the Handbook of Linguistics : Blackwell Reference On

4. The History of Linguistics : The Handbook of Linguistics : Blackwell Reference On... Sayfa 1 / 17 4. The History of Linguistics LYLE CAMPBELL Subject History, Linguistics DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405102520.2002.00006.x 1 Introduction Many “histories” of linguistics have been written over the last two hundred years, and since the 1970s linguistic historiography has become a specialized subfield, with conferences, professional organizations, and journals of its own. Works on the history of linguistics often had such goals as defending a particular school of thought, promoting nationalism in various countries, or focussing on a particular topic or subfield, for example on the history of phonetics. Histories of linguistics often copied from one another, uncritically repeating popular but inaccurate interpretations; they also tended to see the history of linguistics as continuous and cumulative, though more recently some scholars have stressed the discontinuities. Also, the history of linguistics has had to deal with the vastness of the subject matter. Early developments in linguistics were considered part of philosophy, rhetoric, logic, psychology, biology, pedagogy, poetics, and religion, making it difficult to separate the history of linguistics from intellectual history in general, and, as a consequence, work in the history of linguistics has contributed also to the general history of ideas. Still, scholars have often interpreted the past based on modern linguistic thought, distorting how matters were seen in their own time. It is not possible to understand developments in linguistics without taking into account their historical and cultural contexts. In this chapter I attempt to present an overview of the major developments in the history of linguistics, avoiding these difficulties as far as possible. -

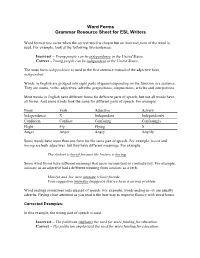

Word Forms Grammar Resource Sheet for ESL Writers

Word Forms Grammar Resource Sheet for ESL Writers Word form errors occur when the correct word is chosen but an incorrect form of the word is used. For example, look at the following two sentences: Incorrect – Young people can be independence in the United States. Correct – Young people can be independent in the United States. The noun form independence is used in the first sentence instead of the adjective form, independent. Words in English are grouped into eight parts of speech depending on the function in a sentence. They are nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, articles and interjections. Most words in English have different forms for different parts of speech, but not all words have all forms. And some words look the same for different parts of speech. For example: Noun Verb Adjective Adverb Independence X Independent Independently Confusion Confuse Confusing Confusingly Flight Fly Flying X Anger Anger Angry Angrily Some words have more than one form for the same part of speech. For example, bored and boring are both adjectives, but they have different meanings. For example: The student is bored because the lecture is boring. Some word forms have different meanings that seem inconsistent or contradictory. For example, intimate as an adjective had a different meaning from intimate as a verb. Marilyn and Joe were intimate (close) friends. Your suggestion intimates (suggests) that we have a serious problem. Word endings sometimes indicate part of speech. For example, words ending in –ly are usually adverbs. Paying close attention as you read is the best way to improve fluency with word forms. -

A Functional Approach to the Choice Between Descriptive, Prescriptive

A Functional Approach to the Choice between Descriptive, Prescriptive and Proscriptive Lexicography Henning Bergenholtz, Centre for Lexicography, Aarhus School of Business, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark ([email protected]) and Rufus H. Gouws, Department of Afrikaans and Dutch, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa ([email protected]) Abstract: In lexicography the concepts of prescription and description have been employed for a long time without there ever being a clear definition of the terms prescription/prescriptive and description/descriptive. This article gives a brief historical account of some of the early uses of these approaches in linguistics and lexicography and argues that, although they have primarily been interpreted as linguistic terms, there is a need for a separate and clearly defined lexicographic application. Contrary to description and prescription, the concept of proscription does not have a linguistic tradition but it has primarily been introduced in the field of lexicography. Different types of prescription, description and proscription are discussed with specific reference to their potential use in dictionaries with text reception and text production as functions. Preferred approaches for the different functions are indicated. It is shown how an optimal use of a prescriptive, descriptive or proscriptive approach could be impeded by a polyfunctional dictionary. Consequently argu- ments are given in favour of monofunctional dictionaries. Keywords: COGNITIVE FUNCTION, COMMUNICATION FUNCTION, DESCRIPTION, DESCRIPTIVE, ENCYCLOPAEDIC, FUNCTIONS, MONOFUNCTIONAL, POLYFUNCTIONAL, PRESCRIPTION, PRESCRIPTIVE, PROSCRIPTION, PROSCRIPTIVE, SEMANTIC, TEXT PRO- DUCTION, TEXT RECEPTION Opsomming: 'n Funksionele benadering tot die keuse tussen deskriptief, preskriptief en proskriptief in die leksikografie. In die leksikografie is die begrippe preskripsie en deskripsie lank gebruik sonder dat daar 'n duidelike definisie van die terme preskrip- sie/preskriptief en deskripsie/deskriptief was. -

The Neat Summary of Linguistics

The Neat Summary of Linguistics Table of Contents Page I Language in perspective 3 1 Introduction 3 2 On the origins of language 4 3 Characterising language 4 4 Structural notions in linguistics 4 4.1 Talking about language and linguistic data 6 5 The grammatical core 6 6 Linguistic levels 6 7 Areas of linguistics 7 II The levels of linguistics 8 1 Phonetics and phonology 8 1.1 Syllable structure 10 1.2 American phonetic transcription 10 1.3 Alphabets and sound systems 12 2 Morphology 13 3 Lexicology 13 4 Syntax 14 4.1 Phrase structure grammar 15 4.2 Deep and surface structure 15 4.3 Transformations 16 4.4 The standard theory 16 5 Semantics 17 6 Pragmatics 18 III Areas and applications 20 1 Sociolinguistics 20 2 Variety studies 20 3 Corpus linguistics 21 4 Language and gender 21 Raymond Hickey The Neat Summary of Linguistics Page 2 of 40 5 Language acquisition 22 6 Language and the brain 23 7 Contrastive linguistics 23 8 Anthropological linguistics 24 IV Language change 25 1 Linguistic schools and language change 26 2 Language contact and language change 26 3 Language typology 27 V Linguistic theory 28 VI Review of linguistics 28 1 Basic distinctions and definitions 28 2 Linguistic levels 29 3 Areas of linguistics 31 VII A brief chronology of English 33 1 External history 33 1.1 The Germanic languages 33 1.2 The settlement of Britain 34 1.3 Chronological summary 36 2 Internal history 37 2.1 Periods in the development of English 37 2.2 Old English 37 2.3 Middle English 38 2.4 Early Modern English 40 Raymond Hickey The Neat Summary of Linguistics Page 3 of 40 I Language in perspective 1 Introduction The goal of linguistics is to provide valid analyses of language structure.