Saving the World's Terrestrial Megafauna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demographic Observations of Mountain Nyala Tragelaphus Buxtoni in A

y & E sit nd er a v n i g d e Evangelista et al., J Biodivers Endanger Species 2015, 3:1 o i r e Journal of B d f S o p l e a c ISSN:n 2332-2543 1 .1000145 r i DOI: 0.4172/2332-2543 e u s o J Biodiversity & Endangered Species Research article Open Access Demographic Observations of Mountain Nyala Tragelaphus Buxtoni in a Controlled Hunting Area, Ethiopia Paul Evangelista1*, Nicholas Young1, David Swift1 and Asrat Wolde1 Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory Colorado State University B254 Fort Collins, Colorado *Corresponding author: Paul Evangelista, Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory Colorado State University B254 Fort Collins, Colorado, Tel: (970) 491-2302; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: December 4, 2014; Accepted date: January 30, 2015; Published date: February 6, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Evangelista P. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The highlands of Ethiopia are inhabited by the culturally and economically significant mountain nyala Tragelaphus buxtoni, an endemic spiral horned antelope. The natural range of this species has become highly fragmented with increasing anthropogenic pressures; driving land conversion in areas previously considered critical mountain nyala habitat. Therefore, baseline demographic data on this species throughout its existing range are needed. Previous studies on mountain nyala demographics have primarily focused on a confined portion of its known range where trophy hunting is not practiced. Our objectives were to estimate group size, proportion of females, age class proportions, and calf and juvenile productivity for a sub-population of mountain nyala where trophy hunting is permitted and compare our results to recent and historical observations. -

The IUCN Wild Pig Challenge 2015

The IUCN Wild Pig Challenge 2015 M ATTHEW L INKIE,JASLINE N G ,ZHI Q I L IM,MUHAMMAD I. LUBIS M ARK R ADEMAKER and E RIK M EIJAARD Abstract Asian mammal species are facing unprecedented Sumatra it is often referred to as lumba lumba pressures from hunting and habitat conversion. Efforts to (Indonesian for dolphin) because local people believe that mitigate these threats often focus on charismatic large-bodied when sounders of up to foraging pigs disappear from species, while many other species or even guilds receive less a forest patch they turn into dolphins and swim to the sea. attention, particularly Asian wild pigs. To address this we de- Also, because of their importance to many communities, veloped a rapid questionnaire survey and administered it to wild pigs are considered to be cultural keystone species. relevant experts to identify the presence, population trends The IUCN/SSC Wild Pig Specialist Group seeks to raise and conservation needs of Asia’s threatened wild pig spe- the profile of wild pigs, draw attention to their plight and cies. The results highlighted geographical differences within support conservation interventions. Of the extant pig spe- species (e.g. the near collapse of bearded pig populations in cies in the Suidae family, occur in Asia and of these are Peninsular Malaysia yet their widespread presence on threatened with extinction (categorized as Vulnerable, Borneo), and knowledge gaps for many endemic species of Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red the Philippines, notably the Critically Endangered Visayan List; IUCN, ), mainly as a result of hunting and loss of warty pig Sus cebifrons. -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Boselaphus Tragocamelus</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2008 Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae) David M. Leslie Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Leslie, David M. Jr., "Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae)" (2008). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 723. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/723 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MAMMALIAN SPECIES 813:1–16 Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae) DAVID M. LESLIE,JR. United States Geological Survey, Oklahoma Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078-3051, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Boselaphus tragocamelus (Pallas, 1766) is a bovid commonly called the nilgai or blue bull and is Asia’s largest antelope. A sexually dimorphic ungulate of large stature and unique coloration, it is the only species in the genus Boselaphus. It is endemic to peninsular India and small parts of Pakistan and Nepal, has been extirpated from Bangladesh, and has been introduced in the United States (Texas), Mexico, South Africa, and Italy. It prefers open grassland and savannas and locally is a significant agricultural pest in India. It is not of special conservation concern and is well represented in zoos and private collections throughout the world. DOI: 10.1644/813.1. -

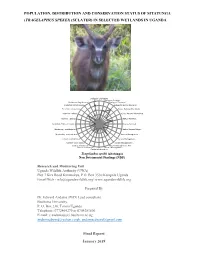

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

An Analysis of Male-Male Aggression in Guanaco Male Groups Paul E

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-1982 An analysis of male-male aggression in guanaco male groups Paul E. Wilson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Paul E., "An analysis of male-male aggression in guanaco male groups" (1982). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 17460. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/17460 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An analysis of male-male aggression in guanaco mal~ groups by Paul E. Wilson, Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Animal Ecology Signatures have been redacted for privacy Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1982 1 417353 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 METHODS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Study Area • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Male Identification and Age Classes • • • • • • • • • 8 Male Group Dynamics • • -

A Giant's Comeback

W INT E R 2 0 1 0 n o s d o D y l l i B Home to elephants, rhinos and more, African Heartlands are conservation landscapes large enough to sustain a diversity of species for centuries to come. In these landscapes— places like Kilimanjaro and Samburu—AWF and its partners are pioneering lasting conservation strate- gies that benefit wildlife and people alike. Inside TH I S ISSUE n e s r u a L a n a h S page 4 These giraffes are members of the only viable population of West African giraffe remaining in the wild. A few herds live in a small AWF Goes to West Africa area in Niger outside Regional Parc W. AWF launches the Regional Parc W Heartland. A Giant’s Comeback t looks like a giraffe, walks like a giraffe, eats totaling a scant 190-200 individuals. All live in like a giraffe and is indeed a giraffe. But a small area—dubbed “the Giraffe Zone”— IGiraffa camelopardalis peralta (the scientific outside the W National Parc in Niger, one of name for the West African giraffe) is a distinct the three national parks that lie in AWF’s new page 6 subspecies of mother nature’s tallest mammal, transboundary Heartland in West Africa (see A Quality Brew having split from a common ancestral popula- pp. 4-5). Conserving the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro tion some 35,000 years ago. This genetic Entering the Zone with good coffee. distinction is apparent in its large orange- Located southeast of Niamey, Niger’s brown skin pattern, which is more lightly- capital, the Giraffe Zone spans just a few hun- colored than that of other giraffes. -

Damaliscus Pygargus Phillipsi – Blesbok

Damaliscus pygargus phillipsi – Blesbok colour pattern (Fabricius et al. 1989). Hybridisation between these taxa threatens the genetic integrity of both subspecies (Skinner & Chimimba 2005). Assessment Rationale Listed as Least Concern, as Blesbok are abundant on both formally and privately protected land. We estimate a minimum mature population size of 54,426 individuals (using a 70% mature population structure) across 678 protected areas and wildlife ranches (counts between 2010 and 2016). There are at least an estimated 17,235 animals (counts between 2013 and 2016) on formally Emmanuel Do Linh San protected areas across the country, with the largest subpopulation occurring on Golden Gate Highlands National Park. The population has increased significantly Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern over three generations (1990–2015) in formally protected National Red List status (2004) Least Concern areas across its range and is similarly suspected to have increased on private lands. Apart from hybridisation with Reasons for change No change Bontebok, there are currently no major threats to its long- Global Red List status (2008) Least Concern term survival. Approximately 69% of Blesbok can be considered genetically pure (A. van Wyk & D. Dalton TOPS listing (NEMBA) None unpubl. data), and stricter translocation policies should be CITES listing None established to prevent the mixing of subspecies. Overall, this subspecies could become a keystone in the Endemic Yes sustainable wildlife economy. The common name, Blesbok, originates from ‘Bles’, the Afrikaans word for a ‘blaze’, which Distribution symbolises the white facial marking running down Historically, the Blesbok ranged across the Highveld from the animal’s horns to its nose, broken only grasslands of the Free State and Gauteng provinces, by the brown band above the eyes (Skinner & extending into northwestern KwaZulu-Natal, and through Chimimba 2005). -

Fitzhenry Yields 2016.Pdf

Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za iii GENERAL ABSTRACT Fallow deer (Dama dama), although not native to South Africa, are abundant in the country and could contribute to domestic food security and economic stability. Nonetheless, this wild ungulate remains overlooked as a protein source and no information exists on their production potential and meat quality in South Africa. The aim of this study was thus to determine the carcass characteristics, meat- and offal-yields, and the physical- and chemical-meat quality attributes of wild fallow deer harvested in South Africa. Gender was considered as a main effect when determining carcass characteristics and yields, while both gender and muscle were considered as main effects in the determination of physical and chemical meat quality attributes. Live weights, warm carcass weights and cold carcass weights were higher (p < 0.05) in male fallow deer (47.4 kg, 29.6 kg, 29.2 kg, respectively) compared with females (41.9 kg, 25.2 kg, 24.7 kg, respectively), as well as in pregnant females (47.5 kg, 28.7 kg, 28.2 kg, respectively) compared with non- pregnant females (32.5 kg, 19.7 kg, 19.3 kg, respectively). -

Evolutionary History of MHC Class I Genes in the Mammalian Order Perissodactyla

J Mol Evol (1999) 49:316–324 © Springer-Verlag New York Inc. 1999 Evolutionary History of MHC Class I Genes in the Mammalian Order Perissodactyla E.C. Holmes,1 S.A. Ellis2 1 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the Epidemiology of Infectious Disease, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK 2 Institute for Animal Health, Compton, Nr Newbury, RG20 7NN, UK Received: 17 November 1998 / Accepted: 7 April 1999 Abstract. We carried out an analysis of partial se- intracellular pathogens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes and quences from expressed major histocompatibility com- thus elicit an immune response. The MHC class I region plex (MHC) class I genes isolated from a range of equid varies in size and complexity between mammalian spe- species and more distantly related members of the mam- cies, most probably due to frequent expansions and con- malian order Perissodactyla. Phylogenetic analysis re- tractions of that area of the genome (Delarbre et al. 1992; vealed a minimum of six groups, five of which contained Vincek et al. 1987). In all examples studied to date genes and alleles that are found in equid species and one (mostly primate and rodent), between one and three group specific to the rhinoceros. Four of the groups con- genes are expressed and have antigen presenting func- tained only one, or very few sequences, indicating the tion—the classical class I, or class Ia, genes. All other presence of relatively nonpolymorphic loci, while an- genes in the region either are not expressed or have un- other group contained the majority of the equid se- known or unrelated functions—the nonclassical class I, quences identified. -

The IUCN Wild Pig Challenge 2015

The IUCN Wild Pig Challenge 2015 M ATTHEW L INKIE,JASLINE N G ,ZHI Q I L IM,MUHAMMAD I. LUBIS M ARK R ADEMAKER and E RIK M EIJAARD Abstract Asian mammal species are facing unprecedented Sumatra it is often referred to as lumba lumba pressures from hunting and habitat conversion. Efforts to (Indonesian for dolphin) because local people believe that mitigate these threats often focus on charismatic large-bodied when sounders of up to foraging pigs disappear from species, while many other species or even guilds receive less a forest patch they turn into dolphins and swim to the sea. attention, particularly Asian wild pigs. To address this we de- Also, because of their importance to many communities, veloped a rapid questionnaire survey and administered it to wild pigs are considered to be cultural keystone species. relevant experts to identify the presence, population trends The IUCN/SSC Wild Pig Specialist Group seeks to raise and conservation needs of Asia’s threatened wild pig spe- the profile of wild pigs, draw attention to their plight and cies. The results highlighted geographical differences within support conservation interventions. Of the extant pig spe- species (e.g. the near collapse of bearded pig populations in cies in the Suidae family, occur in Asia and of these are Peninsular Malaysia yet their widespread presence on threatened with extinction (categorized as Vulnerable, Borneo), and knowledge gaps for many endemic species of Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red the Philippines, notably the Critically Endangered Visayan List; IUCN, ), mainly as a result of hunting and loss of warty pig Sus cebifrons. -

Vega Etal Procroyalsocb Synchronous Diversification

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Frantz, Laurent A. F., Rudzinski, A., Mansyursyah Surya Nugraha, A., Evin, A., Burton, J., Hulme-Beaman, A., Linderholm, A., Barnett, R., Vega, R., Irving-Pease, E., Haile, J., Allen, R., Leus, K., Shephard, J., Hillyer, M., Gillemot, S., van den Hurk, J., Ogle, S., Atofanei, C., Thomas, M., Johansson, F., Haris Mustari, A., Williams, J., Mohamad, K., Siska Damayanti, C., Djuwita Wiryadi, I., Obbles, D., Mona, S., Day, H., Yasin, M., Meker, S., McGuire, J., Evans, B., von Rintelen, T., Hoult, S., Searle, J., Kitchener, A., Macdonald, A., Shaw, D., Hall, R., Galbusera, P. and Larson, G. (2018) Synchronous diversification of Sulawesi’s iconic artiodactyls driven by recent geological events. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Link to official URL (if available): http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2566. This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Synchronous diversification of Sulawesi’s iconic artiodactyls driven by recent geological events Authors Laurent A. F. Frantz1,2,a,*, Anna Rudzinski3,*, Abang Mansyursyah Surya Nugraha4,c,*, , Allowen Evin5,6*, James Burton7,8*, Ardern Hulme-Beaman2,6, Anna Linderholm2,9, Ross Barnett2,10, Rodrigo Vega11 Evan K. Irving-Pease2, James Haile2,10, Richard Allen2, Kristin Leus12,13, Jill Shephard14,15, Mia Hillyer14,16, Sarah Gillemot14, Jeroen van den Hurk14, Sharron Ogle17, Cristina Atofanei11, Mark G.