The Usefulness of Cognitive Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

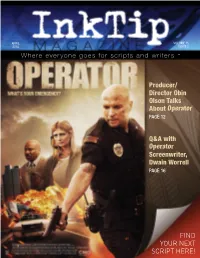

Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12

APRIL VOLUME 15 2015 ISSUE 2 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers ™ Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12 Q&A with Operator Screenwriter, Dwain Worrell PAGE 16 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! Where everyone goes for writers and scripts™ IT’S FAST AND EASY TO FIND THE SCRIPT OR WRITER YOU NEED. WWW.INKTIP.COM A FREE SERVICE FOR ENTERTAINMENT PROFESSIONALS. Peruse this magazine, find the scripts/books you like, and go to www.InkTip.com to search by title or author for access to synopses, resumes and scripts! l For more information, go to: www.InkTip.com. l To register for access, go to: www.InkTip.com and click Joining InkTip for Entertainment Pros l Subscribe to our free newsletter at http://www.inktip.com/ep_newsletters.php Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they can place their scripts on our site. Table of Contents Recent Successes 3, 9, 11 Feature Scripts – Grouped by Genre 7 Industry Endorsements 3 Feature Article: Operator 12 Contest/Festival Winners 4 Q&A: Operator Screenwriter Dwain Worrell 16 Writers Represented by Agents/Managers 4 Get Your Movie on the Cover of InkTip Magazine 18 Teleplays 5 3 Welcome to InkTip! The InkTip Magazine is owned and distributed by InkTip. Recent Successes In this magazine, we provide you with an extensive selection of loglines from all genres for scripts available now on InkTip. Entertainment professionals from Hollywood and all over the Bethany Joy Lenz Options “One of These Days” world come to InkTip because it is a fast and easy way to find Bethany Joy Lenz found “One of These Days” on InkTip, great scripts and talented writers. -

Invictus This Is a Poem 'Invictus' (Unconquered, Undefeated) by William Henley

Invictus This is a Poem 'Invictus' (Unconquered, Undefeated) by William Henley. Nelson Mandela was inspired by the poem, and had it written on a scrap of paper in his prison cell while he was incarcerated for 27 years on Robben Island. Text Out of the night that covers me, Black as the pit from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be For my unconquerable soul. In the fell clutch of circumstance I have not winced nor cried aloud. Under the bludgeonings of chance My head is bloody, but unbowed. Beyond this place of wrath and tears Looms but the Horror of the shade, And yet the menace of the years Finds and shall find me unafraid. It matters not how strait the gate, How charged with punishments the scroll, I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul. "Invictus" is a short Victorian poem by the English poet William Ernest Henley (1849– 1903). It was first published in 1875 in a book called Book of Verses, where it was number four in several poems called Life and Death (Echoes). It originally had no title. ... Background At the age of 12, Henley contracted tuberculosis of the bone. A few years later, the disease progressed to his foot, and physicians announced that the only way to save his life was to amputate directly below the knee. It was amputated when he was 17. Stoicism inspired him to write this poem. Despite his disability, he survived with one foot intact and led an active life until his death at the age of 53. -

CFS Volunteer Yearbook 2019

THE VOLUNTEER YEARBOOK 2019 • Lightbars. • Light-Heads (Surface Mounted Flashers). • Pioneer LiFe™ Battery Operated - Portable Area Lighting. • 11”, 16” & 23” Mini Lightbars. • Pioneer™ Super-LED® Flood / Spot Lights. • Sirens, Switches & Speakers. • Dash / Deck / Visor Lighting. Pioneer LiFe™ 35 CFS Vehicle Intercom Units • 12 or 24v DC. • Crystal Clear Sound. • Waterproof Microphone. • Full Kits Available. • Australian Made! Station Sirens 240v / 415v The "Original" Floating Strainer Float Dock® Strainer Float Dock® strainers are self- levelling, there are no whirlpools Fire Truck Repairs or suction loss! • Striping • Pumps • Nozzles PAC Brackets® • Hoses The Complete answer for • Fire Damage Tools & Equipment stowage. 262 Shearer Drive Phone: 0413 935 463 Seaford South Australia, 5169 Email: [email protected] Contents p20: State Duty Commanders 4: WELCOME 6: REGIONS ROUND UP 13: INCIDENTS 18: OPERATIONS 22: DEPLOYMENTS 27: CELEBRATIONS 30: PROFILES 33: PARTNERSHIPS p15: Mount Compass 35: FRONTLINE SERVICES 41: FRONTLINE SERVICES SUPPORT 48: YOUTH 50: GENERAL 55: SPAM 56: HONOURS 60: MUSEUM 62: CFS FOUNDATION 64: OBITUARIES p22: DEW Tasmania 66: RETIREMENTS 67: CONTACT DETAILS Volunteer Yearbook is an annual publication which captures significant CFS activities and incidents from the past 12 months. The views and opinions expressed through the contributions in this publication are not necessarily those of the SA Country Fire Service or the Government of South Australia. Editorial Team Alison Martin, Brett Williamson and Simone McDonnell CFS Media Line: (08) 8115 3531 Photos: CFS Promotions Unit – www.fire-brigade.asn.au/gallery If you have any feedback about the CFS Volunteer Yearbook or any of our communications, or would like us to cover a story you think should be included, please email CFS.CorporateCommunications@ sa.gov.au p29: Salisbury Celebration 3 Welcome who provide unwavering support to all of our members as they are called to GREG NETTLETON AFSM incidents. -

An Introduction to Cognitive Grammar

COGNITIVE SCIENCE 10, l-40 (1986) An Introduction to Cognitive Grammar RONALD W. LANGACKER University of California, San Diego Cognitive grammar takes a nonstandard view of linguistic semantics and grammatical structure. Meaning is equated with conceptualization. Semantic structures are characterized relative to cognitive domains, and derive their value by construing the content of these domains in a specific fashion. Gram- mar is not a distinct level of linguistic representation, but reduces instead to the structuring and symbolization of conceptual content. All grammatical units are symbolic: Basic categories (e.g., noun ond verb) are held to be notionally definable, and grammatical rules are analyzed as symbolic units that are both complex ond schematic. These concepts permit a revealing account of gram- maticol composition with notable descriptive advantages. Despite the diversity of contemporary linguistic theory, certain fundamental views enjoy a rough consensus and are widely accepted without serious question. Points of general agreement include the following: (a) language is a self-contained system amenable to algorithmic characterization, with suf- ficient autonomy to be studied in essential isolation from broader cognitive concerns; (b) grammar (syntax in particular) is an independent aspect of lin- guistic structure distinct from both lexicon and semantics; and (c) if mean- ing falls within the purview of linguistic analysis, it is properly described by some type of formal logic based on truth conditions. Individual theorists would doubtlessly qualify their assent in various ways, but (a)-(c) certainly come much closer than their denials to representing majority opinion. What follows is a minority report. Since 1976, I have been developing a linguistic theory that departs quite radically from the assumptions of the currently predominant paradigm. -

Discourse in Cognitive Grammar*

Discourse in Cognitive Grammar* RONALD W. LANGACKER Abstract Cognitive Grammar presupposes an inherent and intimate relation between linguistic structures and discourse. Linguistic units are abstracted from usage events, retaining as part of their value any recurring facet of the interactive and discourse context. Linguistic structures thus incorporate discourse expectations and are interpretable as instructions to modify the current discourse state. There are multiple channels of conceptualization and vocalization, including the symbolization of attentional framing by intona- tion groups. An expression is produced and understood with respect to a presupposed discourse context, which shapes and supports its interpreta- tion. Particular contextual applications of linguistic units become entrenched and conventionalized as new, augmented units. As discourse proceeds, conceptual structures are progressively built and modi®ed in accordance with the semantic poles of the expressions employed. While initially mani- festing the speci®c conceptual structuring imposed by these expressions, the structures assembled undergo consolidation to re¯ect the intrinsic conceptual organization of the situations described. This conceptual organization has to be distinguished from grammatical constituency, which is ¯exible, variable, and in no small measure determined by discourse considerations. Keywords: discourse; Cognitive Grammar; intonation unit; grounding; structure building; constituency. 1. Introduction The grounding of language in discourse and social interaction is a central if not a de®ning notion within the functionalist tradition. This is no less true for cognitive linguistics than for other strains of functionalism where the concern is often more visible. My objective here is to elucidate the Cognitive Linguistics 12±2 (2001), 143±188 0936±5907/01/0012±0143 # Walter de Gruyter 144 Ronald W. -

REVIEW ARTICLE Investigations in Cognitive Grammar. by RONALD W

REVIEW ARTICLE Investigations in cognitive grammar. By Ronald W. Langacker . (Cognitive lin - guistics research 42.) Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2009. Pp. 396. ISBN 9783110214352. $70. Reviewed by Jeffrey Heath , University of Michigan 1. Introduction . My assignment is to review, however belatedly, an individual book, but also to comment more broadly on L’s recent work. The task would be easier for a full-time cognitive linguist who could guide us through the fine distinctions be - tween L’s and related models, such as the more cognitive varieties of construction grammar. Your reviewer is a fieldwork linguist, a millipede burrowing through detritus on the forest floor, occasionally catching a ray of theoretical light breaking through the canopy above. After introductory comments and the review proper in §2, I briefly as - sess the relationship between L’s work and functionalism, typology/universals, and syn - chrony/diachrony in §3–5. Cognitive grammar (CG) is a brand name (hence the small capitals) for L’s system. It occupies a central niche within cognitive linguistics (uncapitalized), a growing con - federation of linguists, many of whom, like L, advocate Saussurean form/meaning pair - ings not mediated by an intervening syntactic computational system, recognize constructions as autonomous schemata that are entrenched based on frequent usage , are sympathetic to models of linguistic change based on gradual grammatical - ization, draw no sharp line between criterial semantic features and encyclopedic knowl - edge or between semantics and pragmatics, deny the existence of semantically empty elements such as place-holding expletives and are skeptical of phonologically null mor - phemes and traces, argue that semantic composition is regularly accompanied by se - mantic skewings of input elements, reject truth-conditional (correspondence) semantics in favor of conceptual schemata and prototypes, and inject attentional and perspectival considerations along with temporal dynamicity into grammatical analysis wherever possible. -

Cognitive Linguistics: Looking Back, Looking Forward

This is a repository copy of Cognitive Linguistics: Looking Back, Looking Forward. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/104879/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Divjak, D.S. orcid.org/0000-0001-6825-8508, Levshina, N. and Klavan, J. (2016) Cognitive Linguistics: Looking Back, Looking Forward. Cognitive Linguistics, 27 (4). pp. 447-463. ISSN 0936-5907 https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2016-0095 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Cognitive Linguistics Editorial to the Special Issue: —Looking Back, Looking Forward“ Journal:For Cognitive Preview Linguistics Only Manuscript ID Draft Manuscript Type: research-article Cognitive Commitment, ociosemiotic Commitment, Introspection, Keywords: Experimentation, Quantification ince its conception, Cognitive Linguistics as a theory of language has been enjoying ever increasing success worldwide. -

Killer Movie (2008), Heber Holiday (2007) and Evidence (2013), Starring Stephen Moyer

‘WRITE BEFORE CHRISTMAS’ Cast Bios TORREY DEVITTO (Jessica) – Widely known for her leading role in the current NBC drama “Chicago Med,” Torrey DeVitto is a renowned actress, model and musician. “Chicago Med” hails from the same creators of “Chicago Fire” and “Chicago PD” the latest spin-off focusing on the day-to-day chaos of the team of doctors running the ER. DeVitto plays Natalie Manning, a doctor in the ER Pediatrics division. The show has become the most watched program on Wednesday nights from viewers 18-49 and the series is currently in its fifth season. In 2013, DeVitto was seen as the gorgeous Maggie Hall in the final season of Lifetime’s popular drama, “Army Wives.” She is best known for her stellar recurring roles as Melissa Hastings in the ABC Family/Freeform series “Pretty Little Liars” from 2010 to 2017, Dr. Meredith Fell in The CW fantasy drama “The Vampire Diaries” from 2012 to 2013 and as Carrie in The CW drama “One Tree Hill” from 2008 to 2009 Other notable work includes her roles as Alexandra on the MTV pilot, “Alexandra the Great,” guest-starring on the FBC pilot, “One Big Happy,” guest-starring in “The Untitled Michael Jacobs Pilot” for FBC, and guest-starring on episodes of “Scrubs” (2001), “Dawson's Creek” (1998), “Jack & Bobby (2004), “The King of Queens,” (1998), “ Drake & Josh” (2004), “CSI: Miami” (2002) and “Castle” (2009). DeVitto booked her first lead on the ABC Family series, “Beautiful People” (2005) as aspiring model Karen Kerr. Her film debut was in Starcrossed (2005), and she has appeared in the 2006 movie sequel, I'll Always Know What You Did Last Summer (2006), The Rite (2011) with Anthony Hopkins, Green Flash (2008), Killer Movie (2008), Heber Holiday (2007) and Evidence (2013), starring Stephen Moyer. -

Introducing Sign-Based Construction Grammar IVA N A

September 4, 2012 1 Introducing Sign-Based Construction Grammar IVA N A. SAG,HANS C. BOAS, AND PAUL KAY 1 Background Modern grammatical research,1 at least in the realms of morphosyntax, in- cludes a number of largely nonoverlapping communities that have surpris- ingly little to do with one another. One – the Universal Grammar (UG) camp – is mainly concerned with a particular view of human languages as instantia- tions of a single grammar that is fixed in its general shape. UG researchers put forth highly abstract hypotheses making use of a complex system of repre- sentations, operations, and constraints that are offered as a theory of the rich biological capacity that humans have for language.2 This community eschews writing explicit grammars of individual languages in favor of offering conjec- tures about the ‘parameters of variation’ that modulate the general grammat- ical scheme. These proposals are motivated by small data sets from a variety of languages. A second community, which we will refer to as the Typological (TYP) camp, is concerned with descriptive observations of individual languages, with particular concern for idiosyncrasies and complexities. Many TYP re- searchers eschew formal models (or leave their development to others), while others in this community refer to the theory they embrace as ‘Construction Grammar’ (CxG). 1For comments and valuable discussions, we are grateful to Bill Croft, Chuck Fillmore, Adele Goldberg, Stefan Müller, and Steve Wechsler. We also thank the people mentioned in footnote 8 below. 2The nature of these representations has changed considerably over the years. Seminal works include Chomsky 1965, 1973, 1977, 1981, and 1995. -

Title: One Tree Hill, Ferny Creek, Residents' Submission First Name: Colin Surname: Wnnd

Title: One Tree Hill, Ferny creek, Residents' submission First Name: Colin surname: Wnnd state: victoria Telephone: Main TopicsA summary of our concerns as they pertain to the conditions leading up to the fires, the things that may have contributed to the outcomes, and the findings that will be made by the Bushfire Royal commission as they will affect us too. Acknowledgements: * I acknowledge that my submission will be treated as a public document and may be published, quoted or summarised by the 2009 Victorian Bushfires ~oyalcommission. * I understand that I can be contacted by the Royal Commission in relation to my submission. * I would like to receive future updates about the activities of the Royal Commission. col in wood DG International Media Pty Ltd A.B.N. 93 088 896 155 Ferny VIC 3786 his message may contain confidential and privileged information. Unless you are the intended recipient (or authorised to receive this ?ESrs#; intended recipient), you may not use, copy, disseminate or disclose to anyone the message or any information contained in the message. ~f you have received the message in error, please advise the sender of its incorrect delivery, and then delete the message. Thank you. Contents Urgent requirements Urgent requirements .............................7 Climate change & the weather .....................9 Stay or go? Stayorgo? ...................................10 One Tree HIII. Location Locationmap .................................12 Aerial photograph ..............................13 Tourist destination set amid forest -

Cognitive Grammar with Reference to Passive Construction in Arabic

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture (LLC) March 2017 edition Vol.4 No.1 ISSN 2410-6577 Cognitive Grammar with Reference to Passive Construction in Arabic Dr. Bahaa-eddin Hassan Faculty of Arts, Sohag University, Egypt Abstract The purpose of this study is to examine Cognitive Grammar (CG) theory with reference to the active and the passive voice construction in Arabic. It shows how the cognitive approach to linguistics and construction grammar work together to explain motivation beyond the use of this syntactic construction; therefore, formal structures of language are combined with the cognitive dimension. CG characterizations reveal the limitations of the view that grammatical constructions are autonomous categories. They are interrelated with conceptualization in the framework of cognitive grammar. The study also accounts for the verbs which have active form and passive meaning, and the verbs which have passive form and active meaning. Keywords: Cognitive Grammar, Voice, Arabic, Theme-oriented. 1. Introduction In his Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, Chomsky represented each sentence in a language as having a surface structure and a deep structure. The deep structure represents the semantic component and the surface structure represents the phonological approach. He explained that languages’ deep structures share universal properties which surface structures do not reveal. He proposed transformational grammar to map the deep structure (semantic relations of a sentence) on to the surface structure. Individual languages use different grammatical patterns for their particular set of expressed meanings. Chomsky, then, in Language and Mind, proposed that language relates to mind. Later, in an interview, he emphasized that language represents a state of mind.