Museum Significance Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following work: O’Keeffe, Mornee Jasmin (1991) Over and under: geography and archaeology of the Palm Islands and adjacent continental shelf of North Queensland. Masters Research thesis, James Cook University of North Queensland. Access to this file is available from: https://doi.org/10.25903/5bd64ed3b88c4 Copyright © 1991 Mornee Jasmin O’Keeffe. If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please email [email protected] OVER AND UNDER: Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland Thesis submitted by Mornee Jasmin O'KEEFFE BA (QId) in July 1991 for the Research Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts of the James Cook University of North Queensland RECORD OF USE OF THESIS Author of thesis: Title of thesis: Degree awarded: Date: Persons consulting this thesis must sign the following statement: "I have consulted this thesis and I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author,. and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which ',have obtained from it." NAME ADDRESS SIGNATURE DATE THIS THESIS MUST NOT BE REMOVED FROM THE LIBRARY BUILDING ASD0024 STATEMENT ON ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University of North Queensland will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: "In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which I have obtained from it." Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. -

THE GARDENS REACH of the BRISBANE RIVER Kangaroo Point — Past and Present [By NORMAN S

600 THE GARDENS REACH OF THE BRISBANE RIVER Kangaroo Point — Past and Present [By NORMAN S. PIXLEY, M.B.E., V.R.D., Kt. O.N., F.R.Hist.S.Q.] (Read at the Society's meeting on 24 June 1965.) INTRODUCTION [This paper, entitied the "Gardens Reach of the Brisbane River," describes the growth of shipping from the inception of Brisbane's first port terminal at South Brisbane, which spread and developed in the Gardens Reach. In dealing briefly wkh a period from 1842 to 1927, it men tions some of the vessels which came here and a number of people who travelled in them. In this year of 1965, we take for granted communications in terms of the Telestar which televises in London an inter view as it takes place in New York. News from the world comes to us several times a day from newspapers, television and radio. A letter posted to London brings a reply in less than a week: we can cable or telephone to London or New York. Now let us return to the many years from 1842 onward before the days of the submarine cable and subsequent inven tion of wireless telegraphy by Signor Marconi, when Bris bane's sole means of communication with the outside world was by way of the sea. Ships under sail carried the mails on the long journeys, often prolonged by bad weather; at best, it was many months before replies to letters or despatches could be expected, or news of the safe arrival of travellers receivd. Ships vanished without trace; news of others which were lost came from survivors. -

The Politics of Expediency Queensland

THE POLITICS OF EXPEDIENCY QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT IN THE EIGHTEEN-NINETIES by Jacqueline Mc0ormack University of Queensland, 197^1. Presented In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts to the Department of History, University of Queensland. TABLE OP, CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION SECTION ONE; THE SUBSTANCE OP POLITICS CHAPTER 1. The Men of Politics 1 CHAPTER 2. Politics in the Eighties 21 CHAPTER 3. The Depression 62 CHAPTER 4. Railways 86 CHAPTER 5. Land, Labour & Immigration 102 CHAPTER 6 Separation and Federation 132 CHAPTER 7 The Queensland.National Bank 163 SECTION TWO: THE POLITICS OP REALIGNMENT CHAPTER 8. The General Election of 1888 182 CHAPTER 9. The Coalition of 1890 204 CHAPTER 10. Party Organization 224 CHAPTER 11. The Retreat of Liberalism 239 CHAPTER 12. The 1893 Election 263 SECTION THREE: THE POLITICS.OF EXPEDIENCY CHAPTER 13. The First Nelson Government 283 CHAPTER Ik. The General Election of I896 310 CHAPTER 15. For Want of an Opposition 350 CHAPTER 16. The 1899 Election 350 CHAPTER 17. The Morgan-Browne Coalition 362 CONCLUSION 389 APPENDICES 394 BIBLIOGRAPHY 422 PREFACE The "Nifi^ties" Ms always" exercised a fascination for Australian historians. The decade saw a flowering of Australian literature. It saw tremendous social and economic changes. Partly as a result of these changes, these years saw the rise of a new force in Australian politics - the labour movement. In some colonies, this development was overshadowed by the consolidation of a colonial liberal tradition reaching its culmination in the Deakinite liberalism of the early years of the tlommdhwealth. Developments in Queensland differed from those in the southern colonies. -

Local Heritage Register

Explanatory Notes for Development Assessment Local Heritage Register Amendments to the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, Schedule 8 and 8A of the Integrated Planning Act 1997, the Integrated Planning Regulation 1998, and the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 became effective on 31 March 2008. All aspects of development on a Local Heritage Place in a Local Heritage Register under the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, are code assessable (unless City Plan 2000 requires impact assessment). Those code assessable applications are assessed against the Code in Schedule 2 of the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 and the Heritage Place Code in City Plan 2000. City Plan 2000 makes some aspects of development impact assessable on the site of a Heritage Place and a Heritage Precinct. Heritage Places and Heritage Precincts are identified in the Heritage Register of the Heritage Register Planning Scheme Policy in City Plan 2000. Those impact assessable applications are assessed under the relevant provisions of the City Plan 2000. All aspects of development on land adjoining a Heritage Place or Heritage Precinct are assessable solely under City Plan 2000. ********** For building work on a Local Heritage Place assessable against the Building Act 1975, the Local Government is a concurrence agency. ********** Amendments to the Local Heritage Register are located at the back of the Register. G:\C_P\Heritage\Legal Issues\Amendments to Heritage legislation\20080512 Draft Explanatory Document.doc LOCAL HERITAGE REGISTER (for Section 113 of the Queensland Heritage -

Inner Brisbane Heritage Walk/Drive Booklet

Engineering Heritage Inner Brisbane A Walk / Drive Tour Engineers Australia Queensland Division National Library of Australia Cataloguing- in-Publication entry Title: Engineering heritage inner Brisbane: a walk / drive tour / Engineering Heritage Queensland. Edition: Revised second edition. ISBN: 9780646561684 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Brisbane (Qld.)--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--Buildings, structures, etc.--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Engineers Australia. Queensland Division. Dewey Number: 919.43104 Revised and reprinted 2015 Chelmer Office Services 5/10 Central Avenue Graceville Q 4075 Disclaimer: The information in this publication has been created with all due care, however no warranty is given that this publication is free from error or omission or that the information is the most up-to-date available. In addition, the publication contains references and links to other publications and web sites over which Engineers Australia has no responsibility or control. You should rely on your own enquiries as to the correctness of the contents of the publication or of any of the references and links. Accordingly Engineers Australia and its servants and agents expressly disclaim liability for any act done or omission made on the information contained in the publication and any consequences of any such act or omission. Acknowledgements Engineers Australia, Queensland Division acknowledged the input to the first edition of this publication in 2001 by historical archaeologist Kay Brown for research and text development, historian Heather Harper of the Brisbane City Council Heritage Unit for patience and assistance particularly with the map, the Brisbane City Council for its generous local history grant and for access to and use of its BIMAP facility, the Queensland Maritime Museum Association, the Queensland Museum and the John Oxley Library for permission to reproduce the photographs, and to the late Robin Black and Robyn Black for loan of the pen and ink drawing of the coal wharf. -

Download the Full Article As Pdf ⬇︎

wreck rap Text by Rosemary E. Lunn Photos by Rick Ayrton Dateline: Saturday, 26 May 2018 Destination: SS Kyarra Chart co-ordinates: 50°34,90N; 01°56.59W “Crikey,” I thought, “one hundred years ago today that German U-boat was awfully close to the English coast.” I suddenly felt a bit vulnerable. World War I happened right here—just off the peaceful Dorset shore, not in some far-off French trench. A century ago today, I could well be on a sinking ship. Or dead. In reality, I was sitting, fully kitted up, on Spike—a British dive char- ter boat—waiting for Pete, the Skipper, to yell, “It's time to dive!” Kyarra Wreck Turns 100 Years Old The journey out from Swanage Pier and across the bay had taken 20 minutes, and now we were bobbing up and down over “Her name was taken Thirty metres (98ft) beneath me Denny and Brothers, to a high the wreck site, waiting for slack lay the once elegant Kyarra—a standard (her deck was made water. I stared across the sea to from the aboriginal word twin-masted, schooner-rigged of teak). The Kyarra's passenger land and Anvil Point, a mere mile for a small fillet steel steamer. She had been built accommodation was luxurious; away, thinking about the ship I at the start of the last century in she had 42 First Class Cabins, and was about to dive. of possum fur.” Dunbarton, Scotland, by William her interior and exterior fittings WIKIMEDIA COMMONS / PUBLIC DOMAIN 6 X-RAY MAG : 87 : 2018 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO wreck rap START HERE Scenes from the wreck (above) of the Kyarra (left); Dorset coast (right) retrieve them and made 1914. -

Aboriginal Camps and “Villages” in Southeast Queensland Tim O’Rourke University of Queensland

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 30, Open Papers presented to the 30th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand held on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, July 2-5, 2013. http://www.griffith.edu.au/conference/sahanz-2013/ Tim O’Rourke, “Aboriginal Camps and ‘Villages’ in Southeast Queensland” in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 30, Open, edited by Alexandra Brown and Andrew Leach (Gold Coast, Qld: SAHANZ, 2013), vol. 2, p 851-863. ISBN-10: 0-9876055-0-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9876055-0-4 Aboriginal Camps and “Villages” in Southeast Queensland Tim O’Rourke University of Queensland In the early nineteenth century, European accounts of Southeast Queensland occasionally refer to larger Aboriginal camps as “villages”. Predominantly in coastal locations, the reported clusters of well-thatched domical structures had the appearance of permanent settlements. Elsewhere in the early contact period, and across geographically diverse regions of the continent, Aboriginal camps with certain morphological and architectural characteristics were labelled “villages” by European explorers and settlers. In the Encyclopaedia of Australian Architecture, Paul Memmott’s entry on Aboriginal architecture includes a description of semi- permanent camps under the subheading “Village architecture.” This paper analyses the relatively sparse archival records of nineteenth century Aboriginal camps and settlement patterns along the coastal edge of Southeast Queensland. These data are compared with the settlement patterns of Aboriginal groups in northeastern Queensland, also characterized by semi-sedentary campsites, but where later and different contact histories yield a more comprehensive picture of the built environment. -

Law and Society Across the Pacific: Nevada County, California 1849

LAW AND SOCIETY ACROSS THE PACIFIC Nevada County, California, 1849 - 1860 and Gympie, Queensland, 1867 - 1880 Simon Chapple School of History and Philosophy University of New South Wales February 2010 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgment is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Simon Chapple 2 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the connection between legal history and social history through an analysis of commercial, property and criminal laws, and their practical operation, in Nevada County, California from 1849 to 1860 and the Gympie region, Queensland from 1867 to 1880. By explaining the operation of a broad range of laws in a local context, this thesis seeks to provide a more complete picture of the operation of law in each community and identify the ways in which the law influenced social, political and economic life. -

The Travelling Table

The Travelling Table A tale of ‘Prince Charlie’s table’ and its life with the MacDonald, Campbell, Innes and Boswell families in Scotland, Australia and England, 1746-2016 Carolyn Williams Published by Carolyn Williams Woodford, NSW 2778, Australia Email: [email protected] First published 2016, Second Edition 2017 Copyright © Carolyn Williams. All rights reserved. People Prince Charles Edward Stuart or ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ (1720-1788) Allan MacDonald (c1720-1792) and Flora MacDonald (1722-1790) John Campbell (1770-1827), Annabella Campbell (1774-1826) and family George Innes (1802-1839) and Lorn Innes (née Campbell) (1804-1877) Patrick Boswell (1815-1892) and Annabella Boswell (née Innes) (1826-1914) The Boswell sisters: Jane (1860-1939), Georgina (1862-1951), Margaret (1865-1962) Places Scotland Australia Kingsburgh House, Isle of Skye (c1746-1816) Lochend, Appin, Argyllshire (1816-1821) Hobart and Restdown, Tasmania (1821-1822) Windsor and Old Government House, New South Wales (1822-1823) Bungarribee, Prospect/Blacktown, New South Wales (1823-1828) Capertee Valley and Glen Alice, New South Wales (1828-1841) Parramatta, New South Wales (1841-1843) Port Macquarie and Lake Innes House, New South Wales (1843-1862) Newcastle, New South Wales (1862-1865) Garrallan, Cumnock, Ayrshire (1865-1920) Sandgate House I and II, Ayr (sometime after 1914 to ???) Auchinleck House, Auchinleck/Ochiltree, Ayrshire Cover photo: Antiques Roadshow Series 36 Episode 14 (2014), Exeter Cathedral 1. Image courtesy of John Moore Contents Introduction .……………………………………………………………………………….. 1 At Kingsburgh ……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Appin …………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Emigration …………………………………………………………………………………… 9 The first long journey …………………………………………………………………… 10 A drawing room drama on the high seas ……………………………………… 16 Hobart Town ……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 A sojourn at Windsor …………………………………………………………………… 26 At Bungarribee ……………………………………………………………………………. -

Paintings from the Collection 10 Works In

10works in focus Paintings from the Collection VOLUME 3 10 WORKS IN FOCUS: PAINTINGS FROM THE COLLECTION / VOLUME 3 1 This is the third in a series of 10 Works in Focus publications accompanying the State Library of NSW’s Paintings from the Collection permanent exhibition. The State Library’s exhibitions onsite, online and on tour aim to connect audiences across NSW and beyond to our collections and the stories they tell. www.sl.nsw.gov.au/galleries Members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are respectfully advised that this exhibition and related materials contain the names and images of people who have passed away. ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF COUNTRY The State Library of New South Wales acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the traditional custodians of the land on which the Library stands. We pay respect to Aboriginal Elders past, present and emerging, and extend that respect to other First Nations people. We celebrate the diversity of Aboriginal cultures and languages across NSW. 10works in focus Paintings from the Collection VOLUME 3 Contents 5 Foreword 7 About the exhibition 8 Mr Stanley’s House 10 On a high horse! 12 Shades of grey 14 A rare and honest portrait 16 Acrid smoke and nervous excitement 18 Boys’ day out 22 A standing disgrace to Sydney 24 Poet and painter 26 Miss Mary 28 Affectionately ‘Mullum’ 30 List of works A free exhibition at the State Library of NSW. Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Australia Telephone +61 2 9273 1414 www.sl.nsw.gov.au @statelibrarynsw Curators: Louise Anemaat, Elise Edmonds, -

SPARKING CREATIVITY in NEW YORK NANO GIRL Making Science Fun

ALUMNI PROFILE THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND ALUMNI MAGAZINE | Spring 2014 SPARKING CREATIVITY IN NEW YORK NANO GIRL Making science fun CHARTER SCHOOLS Are they working? Ingenio / Spring 2014 / 1 ALUMNI PROFILE 1/3 DEPOSIT 1/3 12 MONTHS 1/3 24 MONTHS^ WHAT’S STOPPING YOU? 2.9% INTEREST + 3 YEARS FREE SERVICING.* If you’ve been waiting for the perfect time to buy a brand new Volvo, the wait is over. With payments spread over two years at just 2.9% p.a. and three years free servicing, there’s nothing stopping you. BOOK YOUR TEST DRIVE TODAY. 0800 4 VOLVO OR VISIT VOLVOCARS.CO.NZ *Non-transferable Service Plan covers all factory scheduled maintenance for the fi rst 3 years or 60,000km, whichever occurs fi rst. ^Offer based on recommended retail purchase price plus on road costs fees and charges including a documentation fee of $375. This offer is not available in conjunction with any other offers and is valid until 31st December 2014 or while stock lasts. Offer valid for new cars only. 43682 payable by 1/3 deposit, 1/3 in 12 months and the fi nal 1/3 in 24 months with interest calculated at 2.9% p.a. Finance provided by Heartland Bank Limited and subject to normal leading criteria, conditions, For further details please contact your nearest Volvo Dealer. This promotional offer is not available on XC60 D5 AWD Limited Edition. XC70 D5 Kinetic is only eligible for the Service Plan offer at $69,900. # 43682 Volvo Q4 Print Campaign-Ingenio DPS.indd 1 22/10/14 3:12 PM ALUMNI PROFILE 1/3 DEPOSIT 1/3 12 MONTHS 1/3 24 MONTHS^ WHAT’S STOPPING YOU? 2.9% INTEREST + 3 YEARS FREE SERVICING.* If you’ve been waiting for the perfect time to buy a brand new Volvo, the wait is over. -

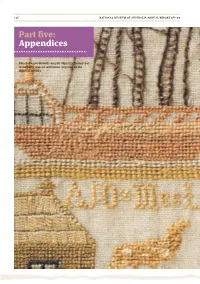

Part Five: Appendices

136 national museum of australia annual report 08–09 Part five: Appendices Detail of a needlework sampler depicting Botany Bay in the early years of settlement, acquired by the Museum in 2009. part five: appendices 137 138 national museum of australia annual report 08–09 Professor Andrea Hull ao Appendix 1 : BA Dip Ed (Sydney University) Council and committees MBA (Melbourne Business School) Executive Education AGSM, Harvard of the National Museum Fellow, Australian Institute of Company Directors of Australia Fellow, Australian Institute of Management Director, Victorian College of the Arts (to March 2009) Council members are appointed under Section 13(2) 12 December 2008 – 11 December 2011 of the National Museum of Australia Act 1980. Attended 2/2 meetings executive member Council Mr Craddock Morton members as at 30 june 2009 BA (Hons) (ANU) Mr Daniel Gilbert am (Chair) Director, National Museum of Australia LLB (University of Sydney) Acting Director: 15 December 2003 – 23 June 2004 Managing Partner, Gilbert+Tobin Director: 24 June 2004 – 23 June 2007 Non-Executive Director, National Australia Bank Limited Reappointed: 24 June 2007 – 23 June 2010 Director, Australian Indigenous Minority Supplier Council Attended 4/4 meetings Member, Prime Minister’s National Policy Commission on Indigenous Housing outgoing members in 2008–09 Councillor, Australian Business Arts Foundation The Hon Tony Staley ao (Chair) 27 March 2009 – 26 March 2012 LLB (Melbourne) Attended 1/1 meeting Chair, Cooperative Research Centres Association Dr John Hirst (Deputy