3 Shanxi As Translocal Imaginary Reforming the Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

The World Bank Shanxi Gas Utilization (P133531) REPORT NO.: RES41698 Public Disclosure Authorized RESTRUCTURING PAPER ON A PROPOSED PROJECT RESTRUCTURING OF SHANXI GAS UTILIZATION APPROVED ON MARCH 28, 2014 TO Public Disclosure Authorized PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA ENERGY & EXTRACTIVES EAST ASIA AND PACIFIC Public Disclosure Authorized Regional Vice President: Victoria Kwakwa Country Director: Martin Raiser Regional Director: Ranjit J. Lamech Practice Manager/Manager: Jie Tang Task Team Leader(s): Ximing Peng Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Shanxi Gas Utilization (P133531) ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CHP Combined Heat and Power Covid-19 Corona Virus Disease -2019 CPS Country Partnership Strategy EA Environmental Assessment FYP Five Year Plan GoC Government of China IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development ICR Implementation Completion Review ISR Implementation Status and Results Report MOF Ministry of Finance PDO Project Development Objective PMO Project Management Office RE Renewable Energy RF Results Framework TA Technical Assistance The World Bank Shanxi Gas Utilization (P133531) Note to Task Teams: The following sections are system generated and can only be edited online in the Portal. BASIC DATA Product Information Project ID Financing Instrument P133531 Investment Project Financing Original EA Category Current EA Category Full Assessment (A) Full Assessment (A) Approval Date Current Closing Date 28-Mar-2014 30-Jun-2020 Organizations Borrower Responsible Agency International Department, Ministry of Finance -

April 12, 1967 Discussion Between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 12, 1967 Discussion between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap Citation: “Discussion between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap,” April 12, 1967, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, CWIHP Working Paper 22, "77 Conversations." http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112156 Summary: Zhou Enlai discusses the class struggle present in China. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation ZHOU ENLAI, CHEN YI AND PHAM VAN DONG, VO NGUYEN GIAP Beijing, 12 April 1967 Zhou Enlai: …In the past ten years, we were conducting another war, a bloodless one: a class struggle. But, it is a matter of fact that among our generals, there are some, [although] not all, who knew very well how to conduct a bloody war, [but] now don’t know how to conduct a bloodless one. They even look down on the masses. The other day while we were on board the plane, I told you that our cultural revolution this time was aimed at overthrowing a group of ruling people in the party who wanted to follow the capitalist path. It was also aimed at destroying the old forces, the old culture, the old ideology, the old customs that were not suitable to the socialist revolution. In one of his speeches last year, Comrade Lin Biao said: In the process of socialist revolution, we have to destroy the “private ownership” of the bourgeoisie, and to construct the “public ownership” of the proletariat. So, for the introduction of the “public ownership” system, who do you rely on? Based on the experience in the 17 years after liberation, Comrade Mao Zedong holds that after seizing power, the proletariat should eliminate the “private ownership” of the bourgeoisie. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD719 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF US$100 MILLION TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FOR A SHANXI GAS UTILIZATION PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized February 26, 2014 China and Mongolia Sustainable Development Unit Sustainable Development Department East Asia and Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective November 1, 2013) Currency Unit = RMB (Chinese Yuan Renminbi) US$ 1 = RMB 6.10 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS bcma Billion cubic meters per annum NDRC National Development and Reform Commission CBM Coal Bed Methane Nm3 Normal Cubic Meters CHP Combined Heat and Power NOx Nitrogen Oxides CNG Compressed Natural Gas PDO Project Development Objective DA Designated Account PMO Project Management Office EA Environmental Assessment QKNGC Qingxu Kaitong Natural Gas Company EHS Environmental, Health and Safety RAP Resettlement Action Plan EIA Environmental Impact RPF Resettlement Policy Framework Assessment EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return SCADA Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition EMP Environmental Management Plan SCPTC Shanxi CBM (Natural Gas) Pipeline -

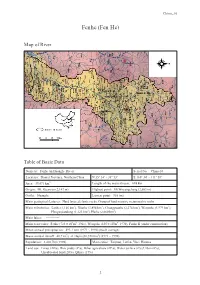

Fenhe (Fen He)

China ―10 Fenhe (Fen He) Map of River Table of Basic Data Name(s): Fenhe (in Huanghe River) Serial No. : China-10 Location: Shanxi Province, Northern China N 35° 34' ~ 38° 53' E 110° 34' ~ 111° 58' Area: 39,471 km2 Length of the main stream: 694 km Origin: Mt. Guancen (2,147 m) Highest point: Mt.Woyangchang (2,603 m) Outlet: Huanghe Lowest point: 365 (m) Main geological features: Hard layered clastic rocks, Group of hard massive metamorphic rocks Main tributaries: Lanhe (1,146 km2), Xiaohe (3,894 km2), Changyuanhe (2,274 km2), Wenyuhe (3,979 km2), Honganjiandong (1,123 km2), Huihe (2,060 km2) Main lakes: ------------ 6 3 6 3 Main reservoirs: Fenhe (723×10 m , 1961), Wenyuhe (105×10 m , 1970), Fenhe II (under construction) Mean annual precipitation: 493.2 mm (1971 ~ 1990) (basin average) Mean annual runoff: 48.7 m3/s at Hejin (38,728 km2) (1971 ~ 1990) Population: 3,410,700 (1998) Main cities: Taiyuan, Linfen, Yuci, Houma Land use: Forest (24%), Rice paddy (2%), Other agriculture (29%), Water surface (2%),Urban (6%), Uncultivated land (20%), Qthers (17%) 3 China ―10 1. General Description The Fenhe is a main tributary of The Yellow River. It is located in the middle of Shanxi province. The main river originates from northwest of Mt. Guanqing and flows from north to south before joining the Yellow River at Wanrong county. It flows through 18 counties and cities, including Ningwu, Jinle, Loufan, Gujiao, and Taiyuan. The catchment area is 39,472 km2 and the main channel length is 693 km. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 © Copyright by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The How and Why of Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China by Jonathan Stanhope Bell Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Chair China’s urban landscape has changed rapidly since political and economic reforms were first adopted at the end of the 1970s. Redevelopment of historic city centers that characterized this change has been rampant and resulted in the loss of significant historic resources. Despite these losses, substantial historic neighborhoods survive and even thrive with some degree of integrity. This dissertation identifies the multiple social, political, and economic factors that contribute to the protection and preservation of these neighborhoods by examining neighborhoods in the cities of Beijing and Pingyao as case studies. One focus of the study is capturing the perspective of residential communities on the value of their neighborhoods and their capacity and willingness to become involved in preservation decision-making. The findings indicate the presence of a complex interplay of public and private interests overlaid by changing policy and economic limitations that are creating new opportunities for public involvement. Although the Pingyao case study represents a largely intact historic city that is also a World Heritage Site, the local ii focus on tourism has disenfranchised residents in order to focus on the perceived needs of tourists. -

SARS CHINA Case Distribution by Prefecture-20 May 20031

Source: Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China SARS Case Distribution by Prefecture(City) in China (Accessed 10:00 20 May 2003) No. Area Prefecture Cumulati Level of local Last Remarks (city) ve transmission reported Probable date Cases 1 Beijing 2444 C 20-May 2 Tianjin 175 C 17-May 3 Hebei 217 Shijiazhuang 24 B 20-May Baoding 31 B 18-May Qinhuangdao 5 UNCERTAIN 7-May Langfang 17 A 14-May Cangzhou 1 NO 26-Apr Tangshan 50 B 18-May Chengde 12 A 20-May Zhangjiakou 66 A 16-May Handan 6 NO 18-May Hengshui 1 NO 7-May Xingtai 4 NO 19-May 4 Shanxi 445 Changzhi 4 NO 8-May Datong 5 NO 8-May Jincheng 1 NO 4-May Jinzhong 49 B 15-May Linfen 18 B 4-May Lvliang 2 NO 13-May Shuozhou 4 NO 17-May Taiyuan 338 C 20-May Xinzhou 4 NO 8-May Yangquan 8 A 10-May Yuncheng 12 A 15-May 5 Inner 287 Mongolia Huhehot 148 C 20-May Baotou 14 B 10-May Bayanzhouer 102 C 15-May 1 Wulanchabu 9 B 6-May Tongliao 1 NO 26-May Xilinguole 10 B 17-May Chifeng 3 NO 6-May 6 Liaoning 3 Huludao 1 NO 26-Apr Liaoyang 1 NO 8-May Dalian 1 NO 12-May 7 Jilin 35 Changchun 34 B 17-May Jilin 1 NO 26-May 8 Heilongjiang 0 9 Shanghai 7 NO 10-May 10 Jiangsu 7 Yancheng 1 NO 2-May Xuzhou 1 NO Before 26 April Nantong 1 NO 30-Apr Huai’an 1 NO 2-May Nanjing 2 A 11-May 1st case of local transmission reported on May 10 Suqian 1 NO 8-May 11 Zhejiang 4 Hangzhou 4 NO 8-May 12 Anhui 10 Fuyang 6 NO 2-May Hefei 1 NO 30-Apr Bengbu 2 NO 10-May Anqing 1 NO 5-May 13 Fujian 3 Sanming 1 NO Before 26 April Xiamen 2 NO Before 26 April 14 Jiangxi 1 Ji’an 1 NO 4-May 15 Shandong 1 2 Jinan 1 NO 22-Apr 16 Henan -

The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013) Junni Wei1*, Alana Hansen2, Qiyong Liu3,4, Yehuan Sun5, Phil Weinstein6, Peng Bi2* 1 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China, 2 Discipline of Public Health, School of Population Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 3 State Key Laboratory for Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China, 4 Shandong University Climate Change and Health Center, Jinan, Shandong, China, 5 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China, 6 Division of Health Sciences, School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, The University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] (JW); [email protected] (PB) Citation: Wei J, Hansen A, Liu Q, Sun Y, Weinstein P, Bi P (2015) The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Abstract Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013). Increased incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9(3): e0003572. doi:10.1371/ journal.pntd.0003572 critical challenge to communicable disease control and public health response. This study aimed to quantify the association between climate variation and notified cases of HFMD in Editor: Rebekah Crockett Kading, Genesis Laboratories, UNITED STATES selected cities of Shanxi Province, and to provide evidence for disease control and preven- tion. -

A Dynamic Schedule Based on Integrated Time Performance Prediction

2009 First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2009) Nanjing, China 26 – 28 December 2009 Pages 1-906 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP0976H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-4909-5 1/6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TRACK 01: HIGH-PERFORMANCE AND PARALLEL COMPUTING A DYNAMIC SCHEDULE BASED ON INTEGRATED TIME PERFORMANCE PREDICTION ......................................................1 Wei Zhou, Jing He, Shaolin Liu, Xien Wang A FORMAL METHOD OF VOLUNTEER COMPUTING .........................................................................................................................5 Yu Wang, Zhijian Wang, Fanfan Zhou A GRID ENVIRONMENT BASED SATELLITE IMAGES PROCESSING.............................................................................................9 X. Zhang, S. Chen, J. Fan, X. Wei A LANGUAGE OF NEUTRAL MODELING COMMAND FOR SYNCHRONIZED COLLABORATIVE DESIGN AMONG HETEROGENEOUS CAD SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................................12 Wanfeng Dou, Xiaodong Song, Xiaoyong Zhang A LOW-ENERGY SET-ASSOCIATIVE I-CACHE DESIGN WITH LAST ACCESSED WAY BASED REPLACEMENT AND PREDICTING ACCESS POLICY.......................................................................................................................16 Zhengxing Li, Quansheng Yang A MEASUREMENT MODEL OF REUSABILITY FOR EVALUATING COMPONENT...................................................................20 Shuoben Bi, Xueshi Dong, Shengjun Xue A M-RSVP RESOURCE SCHEDULING MECHANISM IN PPVOD -

Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure

sustainability Article Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure Yong-Zhi Chang and Suo-Cheng Dong * Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-64889430; Fax: +86-10-6485-4230 Academic Editor: Marc A. Rosen Received: 31 March 2016; Accepted: 16 June 2016; Published: 22 June 2016 Abstract: An index system is established for evaluating the level of sustainable development of resources-based cities, and each index is calculated based on the unascertained measure model for 11 resources-based cities in Shanxi Province in 2013 from three aspects; namely, economic, social, and resources and environment. The result shows that Taiyuan City enjoys a high level of sustainable development and integrated development of economy, society, and resources and environment. Shuozhou, Changzhi, and Jincheng have basically realized sustainable development. However, Yangquan, Linfen, Lvliang, Datong, Jinzhong, Xinzhou and Yuncheng have a low level of sustainable development and urgently require a transition. Finally, for different cities, we propose different countermeasures to improve the level of sustainable development. Keywords: resources-based cities; sustainable development; unascertained measure; transition 1. Introduction In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) proposed the concept of “sustainable development”. In 1996, the first official reference to “sustainable cities” was raised at the Second United Nations Human Settlements Conference, namely, as being comprised of economic growth, social equity, higher quality of life and better coordination between urban areas and the natural environment [1]. -

Research and Application on Typology in the Historical District Renewal

Research and Application on Typology in the Historical District Renewal Author: Min Zhu Supervisor: Abarkan, Abdellah Submitted to Blekinge Tekniska Högskola for the Master of Science Programme in Spatial Planning with an emphasis on Urban Design in China and Europe on the 16th May 2011 Karlskrona, Sweden Abstract As an important constituent part during the urban devel opment, the historical district ha s very important historical and cultural values. At present, with the accelerate devel opment of the whole city, the problem of how to preserve the historical environment and continue the historical essence while make the district adapt to t he modern society at the same time became more an d more serio usly. Ther efore, the top ic about historical district renewal is well worth researching. This paper starts with issues standing in front of the historical district in the background of quick city bo oming and then p oints out the most important pro blem during the renewal process of historical district in China. After that, th is paper introduces typology as a new perspective to solve the problem. Th e main theor ies and ap plication methods are b oth researched in this paper. Based on the sum-up experiences from the example studies, the paper tries to research the concrete process of historical district renewal by using typology as tools, which is mainly from classifica tion, type abstraction and constru ction to type embodiment. And some basic ways of typology application would be summarized after the case study. These theoretical tools and example experiences are all taken into the case study for practice. -

RPD: People's Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns

Resettlement Planning Document Updated Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 42383 January 2011 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project– Youyu County Subproject Prepared by Youyu County Project Management Office (PMO) The updated resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Resettlement Plan Shanxi Small Cities & Towns Development Demonstration Project Resettlement Plan For Youyu County Subproject Youyu County Development and Reform Bureau 30 September, 2008 Shanxi Urban & Rural Design Institute 1 Youyu County ADB Loan Financed Project Management Office Endorsement Letter of Resettlement Plan Youyu County Government has applied for a loan from the ADB to finance the District Heating, Drainage and wastewater network, River improvement, Roads and Water supply Projects. Therefore, the projects must be implemented in compliance with the guidelines and policies of the Asian Development Bank for Social Safeguards. This Resettlement Plan is in line with the key requirements of the Asian Development Bank and will constitute the basis for land acquisition, house demolition and resettlement of the project. The Plan also complies with the laws of the People’s Republic of China, Shanxi Province and Youyu County regulations, as well as with some additional measures and the arrangements for implementation and monitoring for the purpose of achieving better resettlement results. Youyu County ADB Loan Project Office hereby approves the contents of this Resettlement Plan and guarantees the implementation of land acquisition, house demolition, resettlement, compensation and fund budget will comply with this plan. -

Enlightenment from the “Ecological Nature” of Huizhou Ancient Residential Courtyard Landscape

Volume 2, 2019 ISSN: 2663-2551 DOI: 10.31058/j.la.2019.24001 Enlightenment from the “Ecological Nature” of Huizhou Ancient Residential Courtyard Landscape Zhonghua Zhao1* 1 College of Art and Design of Anhui Business and Technology College, Hefei, China Email Address [email protected] (Zhonghua Zhao) *Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 July 2019; Accepted: 31 July 2019; Published: 1 September 2019 Abstract: The courtyard of Huizhou ancient dwellings is a part of the traditional architectural space in Huizhou. Due to the influence of environmental space, the courtyard size is small and narrow, but it has complete functions and reasonable layout. It pays attention to the ecological balance between living space and nature, and shows the cultural concept of ―Harmony between nature and man‖. Based on the survey and actual measurement of landscape features of the courtyards of Huizhou ancient dwellings, this paper describes the design concept of its simple ―ecological nature‖ from aspects of landscape shape characteristics, spatial layout, airport circulation, water feature design, etc. to provide a reference for modern urban landscape design. Keywords: Ecological Nature, Huizhou Ancient Dwelling, Courtyard, Spatial Layout, Water Feature Design 1. Introduction Huizhou ancient dwellings mainly refer to the residential building groups in Huizhou region in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and together with the ancestral halls and the archways in Huizhou, they are called the three unique buildings of Huizhou ancient buildings. The site selection for settlement and landscape layout of Huizhou ancient dwellings respects nature and adapt to local conditions. It emphasizes the ecological planning concept of harmonious coexistence between man and nature.