Improvisation Part I, Marvin Stamm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Anders Griffen Trumpeter Randy Brecker Is Well Known for Working in Montana

INTERVIEw of so many great musicians. TNYCJR: Then you moved to New York and there was so much work it seems like a fairy tale. RB: I came to New York in the late ‘60s and caught the RANDY tail-end of the classic studio days. So I was really in the right place at the right time. Marvin Stamm, Joe Shepley and Burt Collins used me as a sub for some studio dates and I got involved in the classic studio when everybody was there at the same time, wearing suits and ties, you know? Eventually rock and R&B started to kind of encroach into the studio system so T (CONTINUED ON PAGE 42) T O BRECKER B B A N H O J by anders griffen Trumpeter Randy Brecker is well known for working in Montana. Behind the scenes, they were on all these pop various genres and with such artists as Stevie Wonder, and R&B records that came out on Cameo-Parkway, Parliament-Funkadelic, Frank Zappa, Lou Reed, Bruce like Chubby Checker. You know George Young, who Springsteen, Dire Straits, Blue Öyster Cult, Blood, Sweat I got to know really well on the New York studio scene. & Tears, Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Billy Cobham, Larry He was popular on the scene as a virtuoso saxophonist. Coryell, Jaco Pastorius and Charles Mingus. He worked a lot He actually appeared on Ed Sullivan, you can see it on with his brother, tenor saxophonist Michael Brecker, and his website. So, all these things became an early formed The Brecker Brothers band. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

The Basic Caruso

THE BASIC CARUSO Five exercises for trumpet by Markus Stockhausen Exercises ® Aktivraum Musikverlag D- 5 0 6 7 7 K ö l n 2 3 Dedicated with gratitude to Carmine Caruso Dear friends and trumpet colleagues, Finally, I can show you the exercises that I found very beneficial years ago, that have already helped quite a few players. Do them with care and dedication. They are wonderful medicine. Good luck, Markus ® Aktivraum Musikverlag ISMN: M-700233-12-9 Volksgartenstr. 1 Fon: +49 221 9348118 www.aktivraum.de © copyright 2004 by D-50677 Köln Fax: +49 221 9348117 [email protected] Aktivraum Musikverlag 2 Meeting Carmine Caruso 3 In January 1978, I came to New York. It was Nevertheless I continued practicing Carmine‘s a winter with heavy snow, and New York was exercises for quite some years, though not al- peaceful and quiet. I contacted Marvin Stamm, ways with regularity. Within time, I found my whom I admired from his recordings with the own way - being a little more moderate, not Pat Williams Orchestra, and told him that I applying the full system. In this way it worked would like to have lessons with him. He said for me and for many of my students and friends that instead of taking a lesson with him I should to whom I showed them. I called these exercises go to his teacher, Carmine Caruso, which I did. „The Basic Caruso“, and this is what I would Nevertheless, I had a good time with Marvin; he like to now explain to you, dear reader. -

47955 the Musician's Lifeline INT01-192 PRINT REV INT03 08.06.19.Indd

181 Our Contributors Carl Allen: jazz drummer, educator Brian Andres: drummer, educator David Arnay: jazz pianist, composer, educator at University of Southern California Kenny Aronoff: live and studio rock drummer, author Rosa Avila: drummer Jim Babor: percussionist, Los Angeles Philharmonic, educator at University of Southern California Jennifer Barnes: vocalist, arranger, educator at University of North Texas Bob Barry: (jazz) photographer John Beasley: jazz pianist, studio musician, composer, music director John Beck: percussionist, educator (Eastman School of Music, now retired) Bob Becker: xylophone virtuoso, percussionist, composer Shelly Berg: jazz pianist, dean of Frost Music School at University of Miami Chuck Berghofer: jazz bassist, studio musician Julie Berghofer: harpist Charles Bernstein: film composer Ignacio Berroa: Cuban drummer, educator, author Charlie Bisharat: violinist, studio musician Gregg Bissonette: drummer, author, voice-over actor Hal Blaine: legendary studio drummer (Wrecking Crew fame) Bob Breithaupt: drummer, percussionist, educator at Capital University Bruce Broughton: composer, EMMY Chris Brubeck: bassist, bass trombonist, composer Gary Burton: vibes player, educator (Berklee College of Music, now retired), GRAMMY 182 THE MUSICIAN’S LIFELINE Jorge Calandrelli: composer, arranger, GRAMMY Dan Carlin: award-winning engineer, educator at University of Southern California Terri Lyne Carrington: drummer, educator at Berklee College of Music, GRAMMY Ed Carroll: trumpeter, educator at California Institute of -

Bob James Three Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob James Three mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: Three Country: US Released: 1976 Style: Fusion MP3 version RAR size: 1301 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1416 mb WMA version RAR size: 1546 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 503 Other Formats: VQF MMF MP2 AA WAV AU ADX Tracklist Hide Credits One Mint Julep 1 9:09 Composed By – R. Toombs* Women Of Ireland 2 8:06 Composed By – S. Ó Riada* Westchester Lady 3 7:27 Composed By – B. James* Storm King 4 6:36 Composed By – B. James* Jamaica Farewell 5 5:26 Composed By – L. Burgess* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tappen Zee Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Tappen Zee Records, Inc. Licensed From – Castle Communications PLC Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Remastered At – CBS Studios, New York Credits Bass – Gary King (tracks: 1, 2, 5), Will Lee (tracks: 3, 4) Bass Trombone – Dave Taylor* Bass Trombone, Tuba – Dave Bargeron Cello – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken Drums – Andy Newmark (tracks: 1), Harvey Mason (tracks: 2 to 5) Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Flute – Hubert Laws, Jerry Dodgion Flute, Tenor Saxophone – Eddie Daniels Guitar – Eric Gale (tracks: 2 to 4), Hugh McCracken (tracks: 2 to 4), Jeff Mironov (tracks: 1) Harp – Gloria Agostini Keyboards – Bob James Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Photography By [Cover] – Richard Alcorn Producer – Creed Taylor Remastered By – Stew Romain* Supervised By [Re-mastering] – Joe Jorgensen Tenor Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone, Tin Whistle – Grover Washington, Jr. Trombone – Wayne Andre Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Lew Soloff, Marvin Stamm Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Frederick Buldrini, Harold Kohon, Harry Cykman, Lewis Eley, Matthew Raimondi, Max Ellen Notes Originally released in 1976. -

Marvin Stamm Machinations Mp3, Flac, Wma

Marvin Stamm Machinations mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Machinations Country: US Released: 1968 Style: Jazz-Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1199 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1841 mb WMA version RAR size: 1690 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 159 Other Formats: RA MP4 AU TTA MPC AHX XM Tracklist Hide Credits Machinations A1 5:50 Composed By – John Carisi Soadades A2 3:08 Composed By – John Carisi Wedding Dance A3 5:23 Composed By – John Carisi Bleaker Street A4 3:22 Composed By – John Carisi Eruza B1 5:09 Composed By – John Carisi Flute Thing B2 4:56 Composed By – Al Kooper Jes' Plain Bread B3 3:36 Composed By – John Carisi The March Of The Siamese Children B4 3:25 Composed By – Oscar Hammerstein II, Richard Rodgers Sunny B5 3:05 Composed By – Bobby Hebb Credits Alto Saxophone – Dick Spencer (tracks: A3-B5), George Young (tracks: A3-B5), Jerome Richardson (tracks: A1-A2), Jerry Dodgion (tracks: A1-A2) Arranged By – John Carisi (tracks: A1-B5) Baritone Saxophone – Sol Schlinger (tracks: A1-B5) Bass Clarinet – Sol Schlinger (tracks: A1-B5) Bass Guitar – Chet Amsterdam (tracks: A1-B5) Bass Trombone – Pete Phillips* (tracks: A3-B5), Tommy Mitchell* (tracks: A1, A2) Clarinet – Dick Spencer (tracks: A3-B5), George Young (tracks: A3-B5), Jerome Richardson (tracks: A1-A2), Jerry Dodgion (tracks: A1-A2), Mortie Lewis (tracks: A1-B5) Conductor – John Carisi (tracks: A1-B5) Drums – Bill Lavorgna (tracks: A1-B5) Flugelhorn – Bernie Glow (tracks: A1, A2, B1, B3, B4, B5), Burt Collins (tracks: A1, A2, A3, A4, B2), Ernie Royal (tracks: A3-B5), -

Jazz Ensembles Concert.Indd

UPCOMING PERFORMANCES GRIFFIN CONCERT HALL / UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS NOVEMBER 15, 2018 / 7:30 P.M. MUSIC PERFORMANCES Graduate String Trio Recital November 15, 7:30 p.m. ORH Music in the Museum Concert Series / FREE November 20, noon, 6 p.m. GAMA JAZZ ENSEMBLES CONCERT Holiday Spectacular Open Rehearsal for students (ID required) November 28, 7 p.m. GCH Parade of Lights Preview / FREE November 29, 6 p.m. UCA Holiday Spectacular November 29, 7 p.m. GCH Special Guest Don Aliquo Holiday Spectacular December 2, 4 p.m. GCH Concert Orchestra Concert / FREE December 2, 7:30 p.m. ORH SHILO STROMAN DIRECTOR DANCE PERFORMANCES Fall Dance Capstone Concert December 7, 8, 7:30 p.m. UDT WIL SWINDLER Fall Dance Capstone Concert December 8, 2 p.m. UDT DIRECTOR THEATRE PERFORMANCES Big Love by Charles Mee November 16, 7:30 p.m. ST Big Love by Charles Mee November 17, 2 p.m. ST Freshman Theatre Project / FREE November 30, 7:30 p.m. ST www.CSUArtsTickets.com UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS SEASON SPONSORS www.bwui.com www.ramcardplus.com CSU JAZZ ENSEMBLE II SHILO STROMAN, Director Hot House / TADD DAMERON arr. by JACK COOPER Soloist: Nicky Podrez, trumpet Josh Zimmerman, alto sax For All We Know / FRED COOTS (lyrics by SAM M. LEWIS) arr. by JOHN CLAYTON Soloist: Samantha Williams, piano Rivers / MIKE TOMARO Soloists: Nicky Podrez, trumpet Addy Dodd, bari sax Ian Maxwell, drums Lil’Darlin / NEAL HEFTI Soloists: Carolina Knonbauer, trumpet Tenor Madness / SONNY ROLLINS arr. by MARK TAYLOR Soloists: Kevin Rosenberger, tenor sax Noah Gulbrandson, tenor -

Wind and Percussion Divison 1997 Winter Tour

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 2-16-1997 Wind and Percussion Divison 1997 Winter Tour School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Wind and Percussion Divison 1997 Winter Tour" (1997). School of Music Programs. 1487. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/1487 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Music Department I Illinois State University WIND AND PERCUSSION DIVISION I 1997 WINTER TOUR .I WIND SYMPHONY, JAZZ BAND, I WIND AND PERCUSSION FACULTY AND I BOOSEY & HAWKES ARTIST AND SPECIAL GUEST SOLOIST i MARVIN STAMM I Stephen K. Steele, Wind Symphony Conductor Jim Boitos, Jazz Band Conductor I Graduate Assistant I Shawn Neeley Wednesday, February 12, 1997 9:30 am Aurora West High School I 12:00 pm Oswego High School 7:30 pm Bradley-Bourbonnais High School I Thursday, February 13, 1997 8: 15 am Central High School 11: JO am Lincoln way High School 7:30 pm Leyden High School I Friday, February 14 8: 15 am Warren Township High School 2:30 pm Marian Catholic High School I Sunday, February 16 3:00 pm Braden Auditorium I I I I I PROGRAM I I Wind Symphony I Quintessence (1997) David Gillingham I Faculty Brass Quintet and David Collier, Professor of Percussion I I Sketches on a Tudor Psalm (1973) Fisher Tull I I Sonneries (Faculty Woodwind Quintet) Scherzo Eugene Bozza I I from Six Bagatelles Gyorgy Ligeti Alie gro con spirito I I Jazz Band with Soloist Marvin Stamm To he selected from the following: I I Low Down Thad Jones Black Bottom Stomp Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton I I arr. -

Improvisation Part II, Marvin Stamm

TBA Journal - Sept/Oct/Nov 2003 Volume 5, No. 1 Improvisation, Part II by Marvin Stamm What happens when four or five musicians come together to play; what happens within their ‘conversation’? Quite simply, it is a ‘call and response’ to each other. What each musician plays elicits, in a millisecond, a response which then elicits a further response from his colleagues, each in their own way, and on and on. All of this is based on the musician’s thorough knowledge of his subject matter, or, in this case, the tune he is playing. Apply this to people talking together in which they exchange thoughts and ideas based upon their knowledge of a specific subject. In conversation, the more one speaks with others, the more they absorb and expand upon the knowledge and ideas of others. As they attempt to educate themselves and refine their own skills of communication, they, in turn, become better speakers with greater abilities to listen, respond and converse. This is the same process we use to become fine improvisers except that we use our instruments! Of course, we can only improvise to the level of mastery we have acquired on our instruments, a step not required in conversation. Now having developed into a skilled Jazz improviser, one who has trained his or her ear and learned the theories of harmony and rhythm, how does one develop a solo? In my case, I first listen to the style and context of the music, then immerse myself into the feel of the rhythm and harmony and let that elicit a response from me. -

Musical Mosaic

Plano Community Band The presents Musical Mosaic April 23, 2017 at 2:30 pm Eisemann Center CONDUCTORS Joe Frank, Jr., Artistic Director and Principal Conductor, is a retired music educator and band director with over 35 years of experience working with student and adult musicians in Texas and Georgia. He was born in Harlingen, in the Rio Grande Valley, and spent most of his adult years in Richardson and Sherman, Texas. Joe is a third-generation band director. His father, Joe Frank, Sr., was a well-known Texas band and orchestra director, and charter member of the Phi Beta Mu Band Director Hall of Fame. Joe taught for 17 years in the Richardson ISD, where mentors, such as Joe Frank, Sr., Richard Floyd, Tommy Guilbert, Robert Floyd, and Howard Dunn, helped form his concepts of teaching students, as well as interpreting, rehearsing, and performing wind band literature. In 1990, Joe became Director of Bands for the Sherman ISD and helped lead the Sherman Bands to 15 years of successful performances, competitions, and statewide recognition. While living in Athens, Georgia, Joe became director of the Classic City Band and developed a love for working and making music with adults. Joe currently lives in Denison, Texas with his wife, Becky. He is a frequent clinician, consultant, and adjudicator for middle school and high school bands. His daughter, Jessica, currently plays clarinet in the Plano Community Band, and his son, Jeff, is a pediatric neurologist in Oregon. Joe enjoys sailing, golfing, snow skiing, and traveling with Becky. Jim Carter, Associate Conductor, was born in Texas City, Texas, and has made Plano home since 1969, going through the Plano schools and the band program at Plano Senior High. -

Bob James Heads Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob James Heads mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Heads Country: Mexico Released: 1977 Style: Jazz-Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1371 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1824 mb WMA version RAR size: 1445 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 542 Other Formats: APE WAV VQF MMF AHX VOC DMF Tracklist Hide Credits Heads Bass – Alphonso JohnsonClavinet, Electric Piano [Fender Rhodes], Piano, Synthesizer A1 6:40 [Oberheim Polyphonic], Bells [Oberheim Polyphonic Tinkle Bells] – Bob JamesDrums – Steve GaddWritten-By – Bob James We're All Alone Bass – Alphonso JohnsonDrums – Steve GaddElectric Piano [Fender Rhodes], Piano, A2 5:32 Synthesizer [Oberheim Polyphonic] – Bob JamesKeyboards [Acoustic Rhythm] – Richard TeeVibraphone [Vibes] – Michael Mainieri*Written-By – Boz Scaggs I'm In You Alto Saxophone [Alto Sax] – Dave Sanborn*Bass – Will LeeDrums – Alan A3 Schwartzberg*Electric Piano [Fender Rhodes], Synthesizer [Oberheim Polyphonic, Arp 6:47 Odyssey], Clavinet – Bob JamesGuitar – Jeff Layton, Jeff MironovWritten-By – Peter Frampton Night Crawler B1 Alto Saxophone [Alto Sax] – Dave Sanborn*Electric Guitar – Eric GaleElectric Piano 6:17 [Fender Rhodes], Synthesizer [Oberheim Polyphonic] – Bob JamesWritten-By – Bob James You Are So Beautiful Guitar – Eric GalePiano – Bob JamesSoprano Saxophone [Soprano Sax] – Grover B2 6:50 Washington, Jr.Vocals – Gwen Guthrie, Lani Groves, Patti Austin, Vivian CherryWritten-By – Billy Preston, Bruce Fisher One Loving Night Alto Saxophone [Alto Sax] – Dave Sanborn*Arranged By, Adapted By – Bob JamesPiano, B3 5:48 Harpsichord – Bob JamesRecorder [Sopranino] – George MargeTenor Saxophone [Tenor Sax] – Grover Washington, Jr.Written-By – Henry Purcell Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tappan Zee Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – CBS Inc. Manufactured By – Columbia Records Manufactured By – CBS Inc. -

View Program

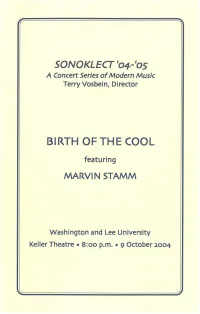

SONOKLECT '04-'05 A Concert Series of Modern Music Terry Vosbein, Director BIRTH OF THE COOL featuring MARVIN STAMM Washington and Lee University Keller Theatre • 8:oo p.m. • 9 October 2004 PROGRAM Move Denzil de Costa Best, arr . John Lewis Jeru Gerry Mulligan Moon Dreams Chummy MacGregor and Johnny Mercer arr. Gil Evans Venus de Milo Gerry Mulligan Budo Miles Davis and Bud Powell arr. John Lewis Deception Miles Davis arr. Gerry Mulligan Boblicity Miles Davis arr. Gil Evans Godchild George Wallington arr. Gerry Mulligan Rocker Gerry Mulligan Israel John Carisi Rouge John Lewis - INTERMISSION - 3 Come and Get It Terry Vosbein To Whom It May Concern Terry Vosbein Inner Heaven Terry Vosbein On the Quai Terry Vosbein Mojitos en la Noche Terry Vosbein A Summer Afternoon Terry Vosbein Here Am I Terry Vosbein Moon-Faced, Starry-Eyed Kurt Weill arr. Terry Vosbein Marvin Stamm Tom Artwick Calvin Smith trumpet alto sax horn Tom Lundberg Don Aliquo Marcus Arnold trombone baritone sax tuba Tony Nalker Harold "Rusty" Holloway Michael Vosbein piano bass drums Terry Vosbein conductor 4 BIRTH OF THE COOL In 1949 Miles Davis and an informal group of forward-thinking musicians gathered to discuss and play contemporary jazz . The meeting place for these musical exchanges was Gil Evans's one-room apartment on New York's west side. They assembled a nine-piece band to try out new arrangements and compositions by such men as Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis and, of course, Gil Evans. The band's unique sound came as much from the skill of the writers as it did from its unique instrumentation: alto sax, baritone sax, trumpet, trombone, French horn, tuba and a three-piece rhythm section .