Investigating Inspirational Leader Communication in an Elite Team Sport Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edition No.2 ANSWERS COPY Every Monday Price 3D WELCOME AND

Edition No.2 ANSWERS COPY Every Monday Price 3d WELCOME AND THANKS 3. Name the Scottish internationalist who played Thanks for all your positive feedback on Test cricket for South Africa. our first edition. KIM ELGIE 4. Jim Telfer coached Scotland’s LIVE RUGBY –WELL, ALMOST 1984 Grand Slam side and was assistant to Ian McGeechan in Great to see all the various re-runs on the 1990 but who was on the field internet and well done to Scottish Rugby in both of these Grand Slams? who were in discussion with the BBC to REFEREE FRED HOWARD show vintage matches. Scottish Rugby TV 5. Who is the most capped show matches on a Friday night. They can Scottish Ladies internationalist? be found at DONNA KENNEDY https://www.scottishrugby.org/fanzone/gri 6. Who has made the greatest d?category=scottish-rugby-tv number of international appearances without scoring a TWITTER AND FACEBOOK point? OWEN FRANKS NZ-108 CAPS As well as our own sites, there is a really 7. Which famous Scot made his good site @StuartCameronTV on Twitter. Scotland International debut Stuart recommends a vintage video from against Wales in 1953? his extensive collection. Our Facebook site BILL McLAREN is Rugby Memories Scotland Group Page 8. Who was the Scotland coach at and we are at @ClubRms on Twitter. the 1987 Rugby World Cup? DERRICK GRANT TOP TEN TEASERS 9. Which former French captain became a painter and sculptor 1. Who scored Scotland’s try in their after retiring from rugby? 9-3 win over Australia at JEAN-PIERRE RIVES Murrayfield in 1968? 10. -

Pride of the Red Roses

TOUCHLINE The Official Newspaper of The RFU September 2017 Issue 204 BROWN BECOMES RFU CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER JOANNA MANNING-COOPER Steve Brown was appointed RFU Chief Executive Officer at the “His passion for rugby, and his commitment to rugby’s values start of this month after an extensive selection process led by a are obvious to everyone who has worked with him, and he will lead Board Nominations Panel and the approval of the RFU Board. He a strong executive team who are committed to making rugby in began his new role on Monday 4 September England the best in the world. ” Brown was Chief Officer, Business Operations at the RFU, and Before joining the RFU, Brown was UK Finance Director at the UK succeeds Ian Ritchie who announced his retirement earlier this year. operation of Abbott, the global, broad-based health care company, for Steve Brown joined the RFU as Chief Financial Officer on June 10, five years after a decade with the company, covering a number of other 2011. He also served as Managing Director of England Rugby 2015, senior financial positions, including UK Pharmaceutical manufacturing responsible for organising the England 2015 Rugby World Cup, and at Abbott’s Paris-based Commercial Regional Headquarters. widely acclaimed as the most successful Rugby World Cup ever. Prior to joining Abbott, he spent three years as the Business The impact of hosting the event saw the highest annual turnover Support Manager and Group Head of Finance for British Energy in the RFU’s history and record investment in rugby. PLC. He originally trained as an accountant in the National Health He was subsequently appointed RFU Chief Officer, Business Service where he held a number of financial roles. -

Scottish Rugby Annual Report 2010/11 Scottish Rugby Annual Report 2010/11 Page 0 3

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 /11 PAGE 0 2 SCOTTISH RUGBY ANNUAL REPORT 2010/11 SCOTTISH RUGBY ANNUAL REPORT 2010/11 PAGE 0 3 CONTENTS President’s Message 04-05 Chairman’s Review 06-09 Finance Director’s Review 10-11 Performance 12-21 Community 22-29 Results and Awards 30-39 Working with Government 40-41 Scottish Rugby Board Report 42-43 Financial Statements 44-59 A Year of Governance 60-63 A Year in Pictures 64-65 Sponsor Acknowledgements 66 FORRESTER MINI FESTIVAL, MAY 2011 PAGE 0 4 SCOTTISH RUGBY ANNUAL REPORT 2010/11 SCOTTISH RUGBY ANNUAL REPORT 2010/11 PAGE 0 5 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE IAN M cLAUCHLAN ONE OF THE GREAT PRIVILEGES and keep encouraging the youngsters to take up and enjoy OF THIS ROLE OF PRESIDENT IS our great game. TRAVELLING ROUND OUR RUGBY On that note, the standard of our school and youth games has also been impressive to witness, giving real grounds for CLUBS AND SEEING, AT FIRST HAND, continued optimism for the future of the game. THE GREAT WORK THAT IS GOING Turning to the bigger lads, another personal highlight from ON WITH SO MANY ENTHUSIASTIC the season was watching the sevens at Melrose in April, AND TALENTED YOUNGSTERS particularly the final game where Melrose won their own ACROSS SCOTLAND. tournament – a fantastic occasion and great weekend of rugby. Moving from sevens to fives, this month’s Islay Beach Early in May I was delighted to be invited to Dalziel Rugby Rugby event was, as ever, a grand spectacle and great fun Club's 21st Festival of Youth Rugby at Dalziel Park in for all, whether playing or watching from the sidelines in Motherwell, the home of the Dalziel Dragons youth section. -

Bill Maclagan's 1891 Lions Johnny Hammond's 1896 Lions

LIONS v SA TEST RECORDS 1891 1997 LIONS v SA TEST RECORDS 1891 1997 BRITISH & IRISH LIONS 1891 3rd Test - 5 September, Newlands, Cape Town BILL MACLAGAN’S 1891 LIONS South Africa 0 British & Irish Lions 4 HT: 0 0 Att: 3,000 South Africa: B Duff; J Hartley, C Vigne, H Versfeld, A Richards (capt); F Guthrie, M Versfeld; B Bisset, E Little, R Shand, C van Renen, J McKendrick, B Heatlie, C Chignell, J Louw British & Irish Lions: W Mitchell; P Clauss, R Aston, W MacLagan (capt), W Wotherspoon; Arthur Rotherham, W Bromet; E Bromet, J Hammond, P Hancock, R MacMillan, E Mayfi eld, A Surtees, R Thompson, T Whittaker 1891 1st Test - 30 July, Crusader’s Ground, Port Elizabeth Scorers: Tries: R Aston, W MacLagan; Con: A Rotherham Referee: Herbert Castens (South Africa) South Africa 0 British & Irish Lions 4 HT: 0 4 Att: 6,000 South Africa: B Duff; M van Buuren, C Vigne, H Boyes, F Guthrie; A Richards, M Versfeld; • The Lions won the series 30 and didn’t • Randolph Aston scored the 29th of his record B Bisset, H Castens (capt), T Devenish, J Louw, E Little, F Alexander, G Merry, F Hamilton concede a point 30 tries on tour in this Test the most ever British & Irish Lions: W Mitchell; P Clauss, R Aston, W MacLagan (capt), Arthur Rotherham; • South Africa wore white jerseys scored by any player on tour in South Africa W Wotherspoon, W Bromet; J Gould, J Hammond, P Hancock, R MacMillan, C Simpson, • Marthinus and Charles Versfeld became • The referee, Herbert Castens, had captained A Surtees, R Thompson, T Whittaker the fi rst brothers to play for South -

The British & Irish Lions Tour to Australia 2013

The British & Irish Lions Tour to Australia 2013 Sponsorship Evaluation Overview 2 CONTENTS Why The British & Irish Lions? 2 – 3 Relationship Development 4 – 7 Employee Engagement 8 – 9 Brand and Corporate Reputation 10 – 13 Brand Exposure 14 – 17 Spectator Engagement 18 – 19 RBWM Sales 20 Activation Maps 21 – 23 32 WHY LIONS? The British & Irish Lions represent the pinnacle of northern hemisphere rugby and is a unique sponsorship in international sport. It represents a once in a lifetime experience for players and fans. Following a successful sponsorship of The Tour in 2009, HSBC became the first ever sponsor to renew its association with The Lions for the 2013 Tour to Hong Kong and Australia. We know that rugby in general appeals to our target audience and the 2013 Tour enabled us to engage with our customers and employees in our key markets of the UK, Ireland, Hong Kong (where the team were playing for the first time ever) and Australia. HSBC Middle East were also actively involved in the sponsorship as an extension of their existing rugby programme. As Principal Partner, HSBC was able to reward and benefit customers and staff, as well as general fans, during an 18 month programme of activity in what became the most integrated sponsorship programme The sponsorship campaign was the bank has ever undertaken. underpinned with the positioning ‘Legendary Journeys’ which captures Specific objectives were set by HSBC for the unique nature and experience of the sponsorship: The Lions for players and fans alike. • Build stronger relationships with our core Through our activation programme, target customers. -

Rugby List 40: July 2018

56 Surrey Street Harfield Village 7708 Cape Town South Africa www.selectbooks.co.za Telephone: 021 424 6955 Please email us at: [email protected] Prices include VAT. Foreign customers are advised that VAT will be deducted from their purchases. We prefer payment by EFT - but Visa, Mastercard, Amex and Diners credit cards are accepted. Approximate Exchange Rates £1 = R18.20 Aus$1 = R.10.00 NZ$1 = R9.30 €1 = R16.00 Turkish Lira1 = R3.00 US$1= R13.80 RUGBY LIST 40: JULY 2018 BOOKS 1 Alfred, Luke. WHEN THE LIONS CAME TO TOWN: the 1974 Rugby Tour to South Africa. Cape Town: Zebra Press, 2014. 252 p.: ill. Paperback. R 220 2 Bath, Richard. THE BRITISH & IRISH LIONS MISCELLANY. London: Vision Sports, 2008. 161 p., [4] p. of ill. Hardcover, d.w. R 100 3 Cleary, Mick. PRIDE RESTORED: the inside story of the Lions in South Africa, 2009; with comments from Ian McGeechan. London: Corinthian Books, 2009. 159 p.: col. ill. Hardcover, d.w. R 150 1 4 Connor, Jeff & Hannan, Martin. ONCE WERE LIONS. London: HarperSport, 2009. xiv, 369 p., [14] p. of ill. (some col.). Hardcover, d.w. R 200 5 Cotton, Fran. MY PRIDE OF LIONS: the British Isles Tour of South Africa 1997. London: Ebury Press, 1997. 224 p., [8] p. of col. ill. Hardcover, d.w., page edges browned. R 200 6 Difford, Ivor D. OUR RUGBY SPRINGBOKS: official souvenir of the visit of the British Rugby Football Team to South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, 1938. Johannesburg: Central News Agency, for the South African Rugby Football Board, 1938. -

ANSWERS July 20Th, 2020 SIGNS of PROGRESS?

ANSWERS July 20th, 2020 SIGNS OF PROGRESS? There are hopeful signs of progress on the Rugby front, so it might not be too long before we can all meet up again. For the moment, we will have to content ourselves with re-runs of great games and live matches from New Zealand. VIRTUAL RUGBY CLUB DINNER What a good idea from our friends at Scottish Rugby Blog Podcast to stage a Virtual Club Dinner. Friday July 24th on Facebook starting at 8.30p.m. It will be available afterwards as well. Dougie Donnelly recalls the Grand Slam and Scott Hastings talKs about Doddie Weir. In between there will be quizzes on OLD Rugby laws, some name the tune quizzes and other fun items. And it’s FREE. www.scottishrugbyblog.co.uK/category/blog/scottish-rugby-blog-podcast/ MYSTERY PLAYERS NO.1 Who is the Lion on the ball? JOHN DAWES Who is providing the bacK-up? GORDON BROWN THE THREE AMIGOS Can you name all three? JIM TELFER, DAVID SOLE, IAN McGEECHAN Who made most Lions PLAYER appearances? IAN McGEECHAN 8 Who made most Scotland PLAYER appearances? DAVID SOLE 44 ALL BLACKS V LIONS Who are the two captains? RONNIE DAWSON AND WILSON WHINERAY What year was this? 1959 ON THE WING Who is the player? IWAN TUKALO What was his first club side? ROYAL HIGH F.P. WESTERING HOME Who is on the charge? GORDON BROWN Who is waiting for the pass? SANDY CARMICHAEL WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS Who are the two players? NICK FARR-JONES and DAVID CAMPESE Which team did they beat in the Final? ENGLAND THE FLYING WINGER Who is going to score? GERALD DAVIES How many Lions appearances did he maKe- 5,10 OR 15? 5 SEVENTH HEAVEN Were you there? What was the best Sevens Tournament that you were at? LINLITHGOW RUGBY MEMORIES Guests and………. -

Olympic Games Inclusion

Player Welfare Strategic Investments Rugby Sevens Tournaments Rugby World Cup Financial Report 2009 YEAR IN REVIEW rugby family celebrates olympic games inclusion 4 providing excellent 12 developing the 22 delivering rugby’s service to member unions game globally major tournaments 6 IRB Council and Committees 14 Strategic investment 24 RWC – the big decisions 8 Key Council/EXCO decisions 16 Training and education 26 The road to New Zealand 2011 10 Member Unions and Regional 18 Game analysis 28 RWC – two years to go Associations 20 Historic year for the Women’s Game 30 Olympic Games 32 RWC Sevens 2009 34 IRB Sevens World Series 36 IRB Toshiba Junior World Championship 38 IRB Junior World Rugby Trophy 40 ANZ Pacific Nations Cup 41 IRB Nations Cup 42 Other International tournaments contents 44 promoting and 54 media and communications 72 financing the investment protecting the game 56 Total Rugby in rugby’s growth and its core values 58 IRB online 74 Financing the global Game 46 Supporting a healthy lifestyle 59 2009 Inductees to the IRB Hall of Fame 76 Financial report and accounts 48 Player welfare 60 IRB World Rankings 92 Meet the team 50 Match officials 62 IRB Awards 2009 52 Anti-doping 64 World results 2009 70 Key fixtures 2010 Year in Review 2009 1 Rugby Reaches Out tO the olympic games 2 International Rugby Board www.irb.com foreword Bernard Lapasset, IRB Chairman, looks back on an historic year 2009 in october, members of the sure that we will now see great growth within world class Rugby and the unique, colourful experience that only a country with such a rich international olympic committee emerging Rugby markets such as China, Russia, India and the USA. -

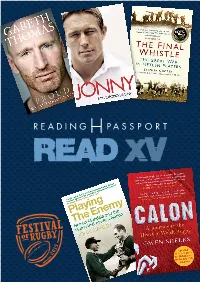

Jonny My Autobiography Jonny Wilkinson Headline

Welcome to the South West Reading Passport 2015, the fourth year of this exciting reading adventure. This year, to celebrate the Rugby World Cup, we’ve selected a irst ifteen of our favourite books about the game. Our featured writer this year is Owen Sheers – and there is lots of information about all the writers on our website www.readingpassport.org. Your local library and the Reading Passport website have even more rugby reading suggestions, as well as many more recommendations from the world of sport in general. Go on, tackle a book! Can you Read XV? White Gold England’s Journey to Rugby World Cup Glory Peter Burns Arena Sport White Gold is a study of how and why England, the biggest and wealthiest rugby country on the planet, never dominated the game it invented on a global scale until Clive Woodward took charge from 1997 to 2004. Ten years on from the greatest triumph in English rugby history, Peter Burns traces the key inluences that shaped Woodward’s attitude to playing and coaching, how he introduced business practices to the sporting arena and created an elite culture for his England players. Playing the Enemy Nelson Mandela and the Game that Made a Nation John Carlin Atlantic Books On 24 June 1995, at Ellis Park in Johannesburg, Nelson Mandela stepped onto a rugby pitch and, in front of an audience of millions worldwide, a new era for South Africa began. Playing the Enemy tells the extraordinary story of how that moment became possible, tracing Mandela’s history from Robben Island to Ellis Park. -

Presenting Scotland at the 2015 Rugby World Cup Cullen, John; Harris, John

Two project players and a kilted Kiwi with a granny from Fife: (re)presenting Scotland at the 2015 Rugby World Cup Cullen, John; Harris, John Published in: Sport in Society DOI: 10.1080/17430437.2018.1555227 Publication date: 2020 Document Version Author accepted manuscript Link to publication in ResearchOnline Citation for published version (Harvard): Cullen, J & Harris, J 2020, 'Two project players and a kilted Kiwi with a granny from Fife: (re)presenting Scotland at the 2015 Rugby World Cup', Sport in Society, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 116-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1555227 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please view our takedown policy at https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/id/eprint/5179 for details of how to contact us. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Two Project Players and a Kilted Kiwi with a Granny from Fife: (Re)presenting Scotland at the 2015 Rugby World Cup John Cullen Glasgow Caledonian University, UK [email protected] John Harris Glasgow Caledonian University, UK [email protected] Corresponding author Abstract Research into the representation of national identities in international sport has developed markedly in the last twenty years. Much of this has focused on the print media portrayal of national identities in mega-events like the Olympic Games and the Football World Cup. -

One Single Code of Rugby John Steele New Rfu Chief Executive

JUNE 2010 / issue 125 RFU THE OFFICIAL TOUCHLINE NEWSPAPER OF THE RFU AND RFUW THE RFU ANNOUNCED at its Council the RFU Annual General Meeting. He said, “I want JOHN STEELE meeting on June 9th that John Steele will to welcome John to the role and give him my become its next Chief Executive Officer public support. The RFU Management Board panel Steele joins from UK Sport where he is Chief have undertaken an exhaustive and professional NEW RFU CHIEF Executive Officer and replaces Francis Baron, who search and identified him as the best candidate. signalled his intent to step down from the role The Management Board approved their last November after nearly 12 years. Since that recommendation which I fully support. EXECUTIVE “I have known John for over ten years in his Peter Thomas time an Executive Recruitment Panel drawn from the RFU Management Board has undertaken a roles at Northampton Saints, on the board of PRL comprehensive and exhaustive search process and latterly at UK Sport. He is a man of integrity which culminated in the appointment. and passion for the game which I believe will be Steele was chosen as having the outstanding important as we lead up to RWC2015.” mix of leadership skills, rugby expertise and Martyn Thomas, Chairman of the RFU Management business experience required for what is one of Board, commented, “We are confident that we have the most complex and demanding roles in sport captured the best person for the role of CEO at the globally. His background in rugby covers a RFU. -

Edition No.2 Every Monday Price 3D WELCOME and THANKS Thanks

Edition No.2 Every Monday Price 3d WELCOME AND THANKS 3. Name the Scottish internationalist who played Test cricket for South Africa. Thanks for all your positive feedback on 4. Jim Telfer coached Scotland’s 1984 our first edition. Grand Slam side and was assistant to Ian McGeechan in 1990 but who was on the LIVE RUGBY –WELL, ALMOST field in both of these Grand Slams? 5. Who is the most capped Scottish Ladies Great to see all the various re-runs on the internationalist? internet and well done to Scottish Rugby 6. Who has made the greatest number of who were in discussion with the BBC to international appearances without scoring show vintage matches. Scottish Rugby TV a point? show matches on a Friday night. They can 7. Which famous Scot made his Scotland be found at International debut against Wales in 1953? 8. Who was the Scotland coach at the 1987 https://www.scottishrugby.org/fanzone/gri Rugby World Cup? d?category=scottish-rugby-tv 9. Which former French captain became a painter and sculptor after retiring from TWITTER AND FACEBOOK rugby? 10. What was Jim Renwick’s junior club? As well as our own sites, there is a really good site @StuartCameronTV on Twitter. ANAGRAMS Stuart recommends a vintage video from his extensive collection. Our Facebook site Can you identify these British Lions is Rugby Memories Scotland Group Page from these anagrams? and we are at @ClubRms on Twitter. 1. AVICUDDDAKHM TOP TEN TEASERS 2. UCYBHRAE 3. IGLEAUWDNILG 1. Who scored Scotland’s try in their 9-3 4.