^Formation to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On-Screen Children's Stories: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

1 On-Screen Children’s Stories: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly Zsofia K. Takacs Promoter: Prof. Dr. Adriana G. Bus Co-promoter: Prof. Dr. Joke M. Voogt 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1: General Introduction ............................................................................ 3 Chapter 2: Affordances and Limitations of Electronic Storybooks for Young Children’s Emergent Literacy ............................................................................... 15 Chapter 3: Benefits and Pitfalls of Multimedia and Interactive Features in Technology-Enhanced Storybooks: A Meta-Analysis ........................................... 63 Chapter 4: Can the Computer Replace the Adult for Storybook Reading? A Meta- Analysis on the Effects of Multimedia Stories as Compared to Sharing Print Stories with an Adult ....................................................................................................... 119 Chapter 5: The Benefits of Motion in Animated Storybooks for Children’s Comprehension. An Eye-tracking Study ............................................................. 157 Chapter 6: General Discussion ........................................................................... 189 Appendix ............................................................................................................ 198 3 Chapter 1 General Introduction 4 Narrative stories like picture storybooks have an important role in the lives of young children, they are a source of cognitive, social and emotional development. Stories support language development -

Edutainment Case Study

What in the World Happened to Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned Carly Shuler The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop Fall 2012 1 © The Joan Ganz Cooney Center 2012. All rights reserved. The mission of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop is to harness digital media teChnologies to advanCe Children’s learning. The Center supports aCtion researCh, enCourages partnerships to ConneCt Child development experts and educators with interactive media and teChnology leaders, and mobilizes publiC and private investment in promising and proven new media teChnologies for Children. For more information, visit www.joanganzCooneyCenter.org. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center has a deep Commitment toward dissemination of useful and timely researCh. Working Closely with our Cooney Fellows, national advisors, media sCholars, and praCtitioners, the Center publishes industry, poliCy, and researCh briefs examining key issues in the field of digital media and learning. No part of this publiCation may be reproduCed or transmitted in any form or by any means, eleCtroniC or meChaniCal, inCluding photoCopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. For permission to reproduCe exCerpts from this report, please ContaCt: Attn: PubliCations Department, The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop One Lincoln Plaza New York, NY 10023 p: 212 595 3456 f: 212 875 7308 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Shuler, C. (2012). Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. -

Ruth Asawa Bibliography

STANFORD UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Ruth Asawa Bibliography Articles, periodicals, and other printed works in chronological order, 1948-2014, followed by bibliographic citations in alphabetical order by author, 1966-2013. Listing is based on clipping files in the Ruth Asawa papers, M1585. 1948 “Tomorrow’s Artists.” Time Magazine August 16, 1948. p.43-44 [Addison Gallery review] [photocopy only] 1952 “How Money Talks This Spring: Shortest Jacket-Longest Run For Your Money.” Vogue February 15, 1952 p.54 [fashion spread with wire sculpture props] [unknown article] Interiors March 1952. p.112-115 [citation only] Lavern Originals showroom brochure. Reprinted from Interiors, March 1952. Whitney Publications, Inc. Photographs of wire sculptures by Alexandre Georges and Joy A. Ross [brochure and clipping with note: “this is the one Stanley Jordan preferred.”] “Home Furnishings Keyed to ‘Fashion.’” New York Times June 17, 1952 [mentions “Alphabet” fabric design] [photocopy only] “Bedding Making High-Fashion News at Englander Quarters.” Retailing Daily June 23, 1952 [mentions “Alphabet” fabric design] [photocopy only] “Predesigned to Fit A Trend.” Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. p.148-159. With photographs of Asawa’s “Alphabet” fabric design on couch, chair, lamp, drapes, etc., and Graduated Circles design by Albert Lanier. All credited to designer Everett Brown “Living Around The Clock with Englander.” Englander advertisement. Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. p.28-29 [“The ‘Foldaway Deluxe’ bed comes only in Alphabet pattern, black and white.”] “What’s Ticking?” Golding Bros. Company, Inc. advertisement. Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. -

Case History: Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? “A Mystery Exploration Game”

Matt Waddell STS 145: Case History Professor Henry Lowood Word Count: 6500 Case History: Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? “A Mystery Exploration Game” Brotherhood at Brøderbund In the summer of 1964, Doug Carlston attended a summer engineering program at Northwestern University: his first computer programming experience. He later worked at Harvard’s Aiken Computation laboratory, and graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1970 with a degree in social relations. In 1975 Carlston received his JD from Harvard law school and established his own law practice in Maine. But he continued to develop games for his Radio Shack computer – the TRS-80 Model 1 – during his college and attorney years. Doug’s programming efforts soon eclipsed his legal practice, and in 1979 he left Maine for Eugene, Oregon to join his younger brother Gary. Doug and Gary Carlston co-founded Brøderbund (pronounced “Brew-der-bund”) Software Inc. in 1980; relatives donated the entirety of their $7,000 in working capital. Indeed, the company’s name reflects its family-based origins – “Brøder” is a blend of the Swedish and Danish words for brother, and “bund” is German for alliance.1 Initially, the “family alliance” sold Doug’s software – Galactic Empire and Galactic Trader – directly to software retailers, but in the summer of 1980 Brøderbund secured an agreement with Japanese software house StarCraft that facilitated both the development and distribution of its arcade-style product line. In 1983 Brøderbund moved from Eugene, Oregon to Novato, California; the company boasted over 40 employees, and its software for the Apple II, Commoodore Vic 20, Commodore 64, and Atari 800 yielded millions of dollars in annual revenue. -

ED433654.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 654 EC 307 399 AUTHOR Hutinger, Patricia L.; Johanson, Joyce; Robinson, Linda; Schneider, Carol TITLE Building InterACTTive Futures. INSTITUTION Western Illinois Univ., Macomb. SPONS AGENCY Special Education Programs (ED/OSERS), Washington, DC. Early Education Program for Children with Disabilities. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 169p.; ACTT = "Activating Children Through Technology." CONTRACT H024D20044 AVAILABLE FROM Macomb Projects 1998, 27 Horrabin Hall, 1 University Circle, Western Illinois University, Macomb, IL 61455; Tel: 309-298-1634; Web site: http://www.mprojects.wiu.edu PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Assistive Devices (for Disabled); Computer Software; *Computer Uses in Education; *Curriculum Development; *Disabilities; *Early Intervention; *Educational Environment; Family Involvement; Input Output Devices; *Learning Activities; Preschool Education; Resource Materials; Severe Disabilities ABSTRACT This curriculum guide presents a comprehensive approach to using technology with children. Chapter 1 presents the curriculum's philosophy and identifies benefits and applications of technology for young children. Chapter 2 looks at the learning environment (including preschool environments, birth to three environments, and environments for children with severe disabilities) and offers guidelines for purchasing and using computer equipment. Chapter 3 is on family participation and offers suggestions for children ages birth to 3,3 to 5, and with severe disabilities, as well as suggestions for conducting a family computer workshop. Chapter 4 is on technology assessment, while chapter 5 focuses on switches and switch adaptations. A potpourri of curriculum activities is described in chapter 6, organized around specific software packages. Procedures for customizing activities are contained in chapter 7, including adaptations for children with motor, visual, or auditory impairment. -

Finding Aid to the Living Books Collection, 1987-2004

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Living Books Collection Finding Aid to the Living Books Collection, 1987-2004 Summary Information Title: Living Books collection Creator: Jeff Schon and Living Books (primary) ID: 116.246 Date: 1987-2004 (inclusive); 1993-1997 (bulk) Extent: 7 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are in English. Abstract: The Living Books collection is a compilation of corporate records, financial documents, product development documentation, marketing materials, publicity clippings, reference materials, and more. The bulk of the materials are dated between 1993 and 1997. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, he has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Living Books collection was donated to The Strong in January 2016 as a gift from Jeff Schon. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 116.246 and were received from Jeff Schon in 6 boxes. Preferred citation for publication: Living Books collection, Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong Processed by: Julia Novakovic, May-June 2016 Controlled Access Terms Personal Names Lee-Merrow, Susan W. Schon, Jeff Corporate Names Brøderbund Brøderbund Software, Inc. -

Chapter 7: Children's Literature Software

Living Literature Chapter 7: Children's Literature Software AWARDS ALA Notable Software for children Terms and criteria for the award: Access link below and select "Current Notable Computer Software." http://www.ala.org/ala/alsc/awardsscholarships/childrensnotable/Default1888.htm The ComputED Gazette is sponsor of two national software awards: For winners visit: http://computedgazette.com/ Education Software Review Awards (EDDIES) in the spring, Best Educational Software Awards (BESSIES) in the fall. SELECTED LITERACY-RELATED SOFTWARE Living Books—Broderbund http://www.broderbund.com/ Activities usually printed in the teacher's guide: Arthur's Birthday (Marc Brown) Arthur's Computer Adventures (Marc Brown) Arthur's Reading Race (Marc Brown) Arthur's Teacher Trouble (Marc Brown) Berenstain Bears Get in a Fight (Stan and Jan Berenstain) Berenstain Bears In the Dark (Stan and Jan Berenstain) Cat in the Hat (Dr. Seuss) Green Eggs and Ham (Dr. Seuss) Just Grandma and Me (Mercer Mayer) Tortoise and the Hare (Aesop) Anderson, R. S., & Speck, B. W. (2001). Using technology in K-8 literacy classrooms. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. Edmark / Riverdeep http://www.riverdeep.net/edmark/ Activities usually printed in the teacher's guide: Talking Walls (Margy Burns Knight) Imagination Express Pyramids Amazing Writing Machine Print Shop Ultimate Student Writing Center Electronic Arts Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. http://harrypotter.ea.com/ Scholastic http://www.scholastic.com Graph Club I Spy Treasure Hunt Magic School Bus Phonics Readers Reading Counts Spelling Studio Wiggleworks . -

Weekly Industry Update

June 11th , 2012 MARKETING NEWS Facebook Impressions Don’t Influence Most Users to Purchase ............................................................ 1 Many Mobile Users Keep Print Newspapers Subscriptions ..................................................................... 2 Offline Ads Drive Mobile Response ......................................................................................................... 3 QR Code Adoption by Merchants Booms ................................................................................................ 4 Sprint Pushes the Envelope to Reduce Its Environmental Footprint ....................................................... 6 PUBLISHING NEWS Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Licenses Living Books ................................................................................... 8 J. V. Rockwell Publishing Acquires the GossRSVP Business from Goss .................................................... 8 MPA's Nina Link to Step Down................................................................................................................. 8 PDF to EPUB Conversion Tools Score Low on Accuracy in VIGC Test .................................................... 10 RETAIL NEWS AEO rolls out Shopkick loyalty program to all stores ............................................................................. 11 America’s “General” store maintains momentum ................................................................................ 11 Customers Like Personalization In-Store More Than Online ................................................................ -

Tools for Language Programs. ICEM Technical Information Bulletin No. 19

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 376 792 IR 016 884 AUTHOR Bezard, M.; Bourguignon, C. TITLE Tools for Language Programs. ICEM Technical Information Bulletin No. 19. INSTITUTION International Council for Educational Media, The Hague (Netherlands). PUB DATE Sep 94 NOTE 24p.; This document is an abstract in English of the dossier "Des outils pour les langues" (February 1994) written by the "Direction de l'Ingenierie educative" of the "Centre National de Documentation Pedagogique" of France. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Audiovisual Aids; Computer Assisted Instruction; Computer Games; Courseware; Electronic Mail; Electronic Text; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Hypermedia; Microcomputers; *Multimedia Instruction; *Multimedia Materials; Optical Data Disks; *Second Language Instruction; Videctape Recordings IDENTIFIERS Audio Cards ABSTRACT This overview of available technologies and how they can be used in teaching languages is divided into three sections. The first, "Multimedia Inputs," examines digitized multimedia tools and their role in language courses, electronic books, encyclopedias and dictionaries, and games, and takes a closer look at "unimedia" products and audiovisual materials. Tools for oral exercises are reviewed and some examples given, including a computer equipped with headset, microphone, and audio card; CD-ROM; and text, sound, and associated images. Discussion of reading on a computer screen covers electronic books, including books -

Fun, Play and Games: What Makes Games Engaging?

Digital Game-Based Learning by Marc Prensky ©2001 Marc Prensky ______________________________________________________________________________________ From Digital Game-Based Learning (McGraw-Hill, 2001) by Marc Prensky Chapter 5 Fun, Play and Games: What Makes Games Engaging Children are into the games body and soul. -C. Everett Koop, former Surgeon General When I watch children playing video games at home or in the arcades, I am impressed with the energy and enthusiasm they devote to the task. … Why can’t we get the same devotion to school lessons as people naturally apply to the things that interest them? -Donald Norman, CEO, Unext You go for it. All the stops are out. Caution is to the wind and you’re battling with everything you have. That’s the real fun of the game. -Dan Dierdorf Computer and videogames are potentially the most engaging pastime in the history of mankind. This is due, in my view, to a combination of twelve elements: 1. Games are a form of fun. That gives us enjoyment and pleasure. 2. Games are form of play. That gives us intense and passionate involvement. 3. Games have rules. That gives us structure. 4. Games have goals. That gives us motivation. 5. Games are interactive. That gives us doing. 6. Games are adaptive. That gives us flow. 7. Games have outcomes and feedback. That gives us learning. 8. Games have win states. That gives us ego gratification. 9. Games have conflict/competition/challenge/opposition. That gives us adrenaline. 10. Games have problem solving. That sparks our creativity. 11. Games have interaction. That gives us social groups. -

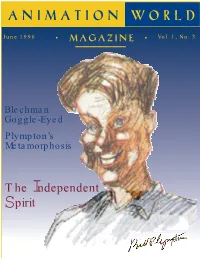

The Ndependent Pirit

June 1996 Vol. 1, No. 3 Blechman Goggle-Eyed Plympton’s Metamorphosis The I ndependent Spirit ANIMATION WORLD MAGAZINE Volume 1, No.3 – June 1996 Editor's Notebook: The Independent Spirit and An Invitation by Harvey Deneroff 3 Plympton’s Metamorphoses by Mark Segall 5 Bill Plympton, the master of the outrageous, is in the midst of making his newest feature, I Married a Strange Person, in which, as Mark Segall reports, the noted animator puts us through some strange changes. Transfixed and Goggle-Eyed by R.O. Blechman 9 R. O. Blechman, who has long charmed us with his films and illustrations, takes a humorous and often sardonic look at the resurgence of all things Disney and what it all means. Shifting Realities: In the Metaphysical Realm Between Live Action and Animation by Suzanne Buchan 12 The Brothers Quay, those enigmatic masters of stop motion, have now come forth with The Institute Benjamenta, their first “live-action” feature. Suzanne Buchan takes a look at the film and their career. Instinctive Decisions -- Dave Borthwick, Radical Independent by Frankie Kowalski 16 Dave Borthwick and bolexbrothers studios represent the best of Bristol’s thriving animation underground. Their productions include the feature-length Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb, which is a far cry from the usual version of the Grimm fairy tale.. Don Bluth Goes Independent by Jerry Beck 20 When Don Bluth suddenly left Disney in the late 1970s to strike out on his own, it led to a chain of events that sparked today’s renaissance in feature animation. Jerry Beck provides a brief memoir of the days when Bluth appeared to be animation’s white knight and could do no wrong. -

Sonlight Curriculum

SONLIGHT FAMILY STORIES TOUCHING TESTIMONIALS FROM OUR CUSTOMERS AROUND THE WORLD We all love a good story. I’ve read about 13,000 books in my quest to find the absolute best stories on which to build Sonlight Curriculum. But those stories aren’t the most important ones in Sonlight’s view. The most important stories are the ones that families like yours live out every day. They are the stories of families growing closer, learning together, and living out the adventures God has for them. As Sonlight celebrates 25 years of inspiring a love to learn, we compiled this book to share some of these stories with you. So browse the photos and read the funny, touching, and heartfelt anecdotes from families whose lives have been changed thanks to their decision to teach their children at home with Sonlight. As you read, be encouraged at the hope of where your own family story could take you! – Sarita Holzmann Homeschool Mom and President of Sonlight Curriculum vii It was Box Day for my pre-k'er Beckett (age 4) and he was so excited. He managed to open the box before I could find the scissors and immediately started going through his new books. He piled several on his lap and announced that those were the ones he wanted me to read to him right then at that moment. I love homeschooling my kids, of getting to read to them, answer their questions, love seeing SL books spark interest in their eyes. And I especially love when they'll bring something up out of the blue that we've learned about in school.