1 Subject, Object, Improv: John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deep Listening with Pauline

DEEP LISTENING WITH PAULINE Celebrating the life and legacy of postwar composer and sound artist Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016) Guest curated by Lucas Artists Composer Fellow Luciano Chessa “Listen to everything all of the time and remind yourself when you are not listening.” —Pauline Oliveros “I first collaborated with Pauline in 2009 when I invited her to create a score for my Orchestra of Futurist Noise Intoners. We became friends and I had the wonderful opportunity to work and interact with her on many occasions in the subsequent years. In early November, I was asked by Montalvo’s curatorial team to contact Pauline to see if she would be open to participating in Montalvo’s summer outdoor exhibition Now Hear This! I reached out and she answered immediately, as was customary. On November 24, 2016, only a couple of days after this Montalvo-related exchange, Pauline sadly left us. The idea to transform her participation in Now Hear This! into a celebration and exploration of her work and legacy evolved spontaneously, naturally. A Pauline event was born with no pretense to be exhaustive, with no ambition of creating a retrospective of any sort, and no other necessity than to simply thank her for the gifts she has given us. The guiding principle of this celebration is Pauline’s own notion that the performer is first and foremost a listener. Our homage features three musicians who are familiar with Pauline’s aesthetics and take her work as a point of inspiration (Ashley Bellouin, Elana Mann and Fernando Vigueras), and two of Pauline’s longtime collaborators: San Francisco Tape Center’s co-founder Ramón Sender Barayón, and Deep Listening Band’s co-founder Stuart Dempster. -

ICMC Article Final

THE EXPANDED INSTRUMENT SYSTEM: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS David Gamper with Pauline Oliveros Pauline Oliveros Foundation PO Box 1956 Kingston, NY 12402 <[email protected]>, <[email protected]> Abstract I demonstrate the current configuration and user interface of the Expanded Instrument System, an improvising performance environment for acoustic musicians used extensively by Pauline Oliveros and Deep Listening Band. The constraints from which this configuration emerged are discussed and provide the rationale for the design and implementation decisions made, including those for a custom MIDI interface for the vintage Lexicon PCM 42 delay. I. Introduction The Expanded Instrument System (EIS) is a performer controlled delay based network of digital sound processing devices designed to be an improvising environment for acoustic musicians. Since its presentation at the 1991 International Computer Music Conference [Oliveros and Panaiotis, 1991] the EIS has undergone a radical shift in implementation while maintaining its roots firmly in the work of Pauline Oliveros beginning in the late fifties [Oliveros, 1995]. In the current configuration each performer has appropriate microphones, a Macintosh computer running Opcode’s Max program and a collection of sound processing electronic devices. Foot switches and “expression” type foot pedals are interpreted by programming in Max to control the signal routing from the microphones among the sound processors, as well as control certain functions of the processors themselves. Each of these set-ups is referred to as an EIS station. Sound outputs from each station are distributed to at least four speakers encircling the performance and audience space. On the station’s computer screen [Figure 1], the performer sees a display of the available functions to be controlled and their current state. -

Track Listing

Pauline Oliveros American electronics player and accordionist (May 30, 1932—November 24, 2016) Track listing 1. title: Mnemonics II (09:53) personnel: Pauline Oliveros (tapes, electronics) album title (format): Reverberations: Tape & Electronic Music 1961-1970 (cdx12) label (country) (catalog number): Important Records. (US) (IMPREC352 ) recording date: 1964-6 release date: 2012 1 2. title: Bye Bye Butterfly (08:07) personnel: Pauline Oliveros (tapes, electronics) album title (format): Women in Electronic Music 1977 (cd) label (country) (catalog number): Composers Recordings Inc. (US) (CRI 728) recording date: 1965 release date: 1997 3. title: Ione (17:37) personnel: Pauline Oliveros (accordion), Stuart Dempster (trombone, didgeridoo) album title (format): Deep Listening (cd) label (country) (catalog number): New Albion (US) (NA 022) release date: 1989 4. title: Texas Travel Texture, Part I (10:23) ensemble: Deep Listening Band personnel: Pauline Oliveros (accordion, conch, voice, electronics), Ellen Fullman (long- stringed instrument), Panaiotis (computer), David Gamper (flute, ocarina, voice, long- stringed instrument), Elise Gould (long-stringed instrument), Nigel Jacobs (long-stringed instrument), Stuart Dempster (trombone, didgeridoo, conch, voice, electronics) album title (format): Suspended Music (cd) label (country) (catalog number): Periplum (US) (P0010) release date: 1997 5. title: Ghost Women ensemble: New Circle Five personnel: Susie Ibarra (percussion), Pauline Oliveros (accordion), Kristin Norderval (soprano), Rosi Hertlein (violin, voice), Monique Buzzarté (trombone) album title (format): Dreaming Wide Awake (cd) label (country) (catalog number): Deep Listening (US) (DL-20) release date: 2003 duration: 12:39 Links: Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauline_Oliveros Discogs.com website: http://www.discogs.com/artist/Pauline+Oliveros official site: http://www.paulineoliveros.us/ Deep Listening Institute: http://deeplistening.org/site/ 2 . -

Deep Listening, Touching Sound

WHAT IS DEEP LISTENING? What is Deep Listening? There’s more to listening than meets the ear. Pauline Oliveros describes Deep Listening as “listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what one is doing.” Basically Deep Listening, as developed by Oliveros, explores the difference between the involuntary nature of hearing and the voluntary, selective nature – exclusive and inclusive -- of listening. The practice includes bodywork, sonic meditations, interactive performance, listening to the sounds of daily life, nature, one’s own thoughts, imagination and dreams, and listening to listening itself. It cultivates a heightened awareness of the sonic environment, both external and internal, and promotes experimentation, improvisation, collaboration, playfulness and other creative skills vital to personal and community growth. The Deep Listening: Art/Science conference provides artists, educators, and researchers an opportunity to creatively share ideas related to the practice, philosophy and science of Deep Listening. Developed by com- poser and educator Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening is an embodied meditative practice of enhancing one’s attention to listening. Deep Listening began over 40 years ago with Oliveros’ Sonic Meditations and organi- cally evolved through performances, workshops and retreats. Deep Listening relates to a broad spectrum of other embodied practices across cultures and can be applied to a wide range of academic fields and disci- plines. This includes, but not limited to: • theories of cognitive -

Deep Listening Band and Friends - Studio 2, 7:30 PM - 9:30 PM Saturday

ORGANIZATION & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Organization & Deep Listening Institute, LTD Acknowledgements Board of Trustees David Felton, President Conference/Festival Organization Jonas Braasch, Vice-President Antonio Bovoso, Treasurer Lisa Barnard Kelley – Conference Director Olivia Robinson, Secretary Brian Cook - Technical Director/Studio Two Tom Bickley Lindsay Karty - Technical Director/Studio BETA Viv Corringham James (Zovi) McEntee - Program Director Orville Dale James Perley - Documentation Director Brenda Hutchinson IONE Conference/Festival Committee Norman Lowrey Pauline Oliveros Curtis Bahn Johannes Welsch Tom Bickley Doug Van Nort Jonas Braasch Nao Bustamante Staff Caren Canier Michael Century Deep Listening Institute: Viv Corringham Pauline Oliveros, Executive Director Nicholas DeMaison IONE, Artistic Director Tomie Hahn Tomie Hahn, Director of Center for Deep Listening Brenda Hutchinson Lisa Barnard Kelley, Events & Marketing IONE Emily Halstein, Administrative & Finance Manager Kathy High Al Margolis, Label & Catalog Manager Ade Knowles Nico Bovoso, Graphic Designer Ted Krueger Daniel Reifsteck, Intern Michael Leczinsky Norman Lowrey Olivia Robinson Volunteers Silvia Ruzanka Eric Ameres Phuong Nguyen Igor Vamos Ken Appleman Daniel Reifsteck Doug Van Nort David Arner Angel Rizo Brent Campbell Nina Ryser Program Sub-Committee Renee Coulombe Shelley Salant Björn Ericksson Marian Schoettle Tom Bickley Brenda Hutchinson Will Gluck John Schoonover Curtis Bahn IONE Billy Halibut Matt Wellins Brian Cook Michael Leczinsky Anina B Ivry-Block -

ICAD 2007 Proceedings

Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Auditory Display, Montréal, Canada, June 26-29, 2007 IMPROVISING WITH SPACES Pauline Oliveros Arts Department Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute 110 8th Street, Troy, NY 12180 [email protected] This paper explores qualitative changes that occur in voices by sound may also divide the attention of the listener, distracting and instruments in relationships with changing spaces ordinarily from a fuller consciousness of sound. held in a stationary paradigm of performance practice, spatial transformations and the effect on sounds in multi-channel The desirable integration of looking and listening during which speaker systems. Digital technology allows one to compose and the two modes – visual and auditory – are approximately equal improvise with acoustical characteristics and change the and mutually supportive comes with conscious practice. apparent space during a musical performance. Sounds can move in space and space can morph and change affecting the sounds. Listening with eyes closed in order to heighten and develop Space is an integral part of sound. One cannot exist without the auditory attention is especially recommended. This is also true other. Varieties of sounds and spaces combine in symbiotic for performers if they are not reading music or trying deliberately relationships that range from very limited to very powerful for to draw attention to themselves. the interweaving expressions of the music, architectures and audiences. If a performer is modeling listening the audience is likely to sense or feel the listening and be inspired to listen as well. [Keywords: Spatial Music, Surround Sound] This brief non-technical paper references the practice of Deep Listening®1, improvisation2, the Expanded Instrument System (EIS)3, acoustics as a parameter of music4 and includes selected recorded examples with differing acoustical characteristics for the music. -

Pauline Oliveros and the Quest for Musical Utopia Hannah Christina Mclaughlin Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 2018-05-01 Pauline Oliveros and the Quest for Musical Utopia Hannah Christina McLaughlin Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation McLaughlin, Hannah Christina, "Pauline Oliveros and the Quest for Musical Utopia" (2018). All Theses and Dissertations. 6828. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6828 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Pauline Oliveros and the Quest for Musical Utopia Hannah Christina Johnson McLaughlin A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steven Johnson, Chair Jeremy Grimshaw Michael Hicks School of Music Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Hannah Christina Johnson McLaughlin All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Pauline Oliveros and the Quest for Musical Utopia Hannah Christina Johnson McLaughlin School of Music, BYU Master of Arts This thesis discusses music’s role in utopian community-building by using a case study of a specific composer, Pauline Oliveros, who believed her work could provide a positive “pathway to the future” resembling other utopian visions. The questions of utopian intent, potential, and method are explored through an analysis of Oliveros’s untraditional scores, as well as an exploration of Oliveros’s writings and secondary accounts from members of the Deep Listening community. -

Pauline Oliveros Papers

Page 1 Pauline Oliveros Papers Series 1: Compositions Arrangement: Arranged alphabetically. Scope and Contents: Series comprises Oliveros' composition files containing original and copies of sketches and diagrams related to the process; notes on the compositions; correspondence regarding the compositions; and both originals and copies of manuscripts; and some photographs Box Folder Description Date 1 1 Aga 1984 October 20 1 2 All Fours for the Drum Bum (For Fritz Hauser) 1990 1 3 Angels and Demons 1980 1 4 Antigone's Dream 1999 1 5 AOK 1969 - 1996 1 6 Approaches and Departures - Appearances and Disappearances 1995 1 7 Arctic Air / Alpine Air / Pacific Air 1989 - 1992 1 8 Autobiography of Lady Steinway, The 1989 1 9 Bandoneon Music various dates 1 10 Beyond the Mysterious Silence. Approaches and Departures 1996 1 11 Blue Heron (For bass and piano) 2006 October 10 1 12 Bonn Feier 1971, 1977 1 13 Breaking Boundaries. For piano or piano ensemble. (For Atlantic Center for the Arts) 1996 December 7 1 14 Buffalo Jam. [Amtrak to Buffalo] 1982 February 15 1 15 Bye bye Butterfly undated 1 16 Car Mandala 1988 October 17 1 17 Cheap Commissions 1986 April 1 18 Circuitry for Percussion 1967, 2003 1 19 Collective Environmental Composition 1975 June 2 1 20 Contenders, The 1990 1 21 Crone Music 1990 1 22 Dance undated 1 23 Deep Dish Dreaming 1992 1 24 Deep Listening undated 1 25 Deep Listening Pieces 1979 1 26 Double X [In Sierra Nevada] 1979 August 1 27 Dream Gates (For Marimolin) 1989 1 28 Dream Horse Spiel (Commissioned by Westdeutsche Rundfunk, Cologne) 1988-1989, 2004 1 29 Dream Horse Spiel. -

Stuart Dempster William Benjamin Mcilwain

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Select Contributions and Commissions in Solo Trombone Repertoire by Trombonist Innovator and Pioneer: Stuart Dempster William Benjamin McIlwain Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC SELECT CONTRIBUTIONS AND COMMISSIONS IN SOLO TROMBONE REPERTOIRE BY TROMBONIST INNOVATOR AND PIONEER: STUART DEMPSTER By WILLIAM BENJAMIN MCILWAIN A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the treatise of William Benjamin McIlwain defended on October 14, 2010. __________________________________ John Drew Professor Directing Treatise __________________________________ Richard Clary University Representative __________________________________ Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicate this to my loving wife, Jackie, for her support, guidance and encouragement throughout our lives together. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge Stuart Dempster‘s unwavering support and willingness to see this project through since its inception. In addition to his candor in the interview process, Mr. Dempster put me in contact with colleagues and former students who have helped in my research. Also, he took an active role in the editing process of the transcripts and treatise, all of his own accord. It has been a true honor and privilege to learn from him during this process. Thank you to all of Mr. Dempster‘s students and colleagues that provided insight during the research process. -

Print/Download This Article (PDF)

American Music Review The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XLVII, Issue 1 Fall 2017 Roots for Deep Listening in Oliveros’s Bye Bye Butterfly Sarah Weaver, Stony Brook University Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016) is a luminary in American music. She was a pioneer in a number of fields, including composition, improvisation, tape and electronic music, and accordion performance. Oliveros was also the founder of Deep Listening, a practice that is “based upon principles of improvisation, elec- tronic music, ritual, teaching and meditation,” and that is “designed to inspire both trained and untrained musicians to practice the art of listening and responding to environmental conditions in solo and ensemble situations.”1 While Deep Listening permeated Oliveros’s output since the establishment of The Deep Listening Band in 1988, the first Deep Listening Retreat in 1991, and the Deep Listening programs that continue through present time, the literature surrounding Oliveros’s work tends to portray an historical gap between Deep Listening and her earlier works, such as her acclaimed tape composition Bye Bye Butterfly, a two-channel, eight-minute tape composition made at the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1965. A main rea- son for this gap is an over- emphasis on Oliveros’s status as a female composer, rather than a direct engagement with the musical elements of her work. This has caused Bye Bye Butterfly to be interpreted prominently as a feminist work, even though, according to Oliveros herself, the work was not intended this way in the first place.2 Furthermore, historical significance tends to be placed on this piece, and on its relationship with Pauline Oliveros at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, c. -

Program Notes

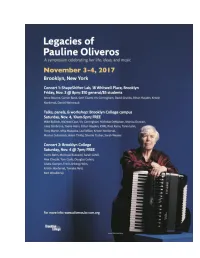

Acknowledgements Many thanks to the people and organizations that have made this event possible: ● Conservatory of Music of Brooklyn College, Stephanie JensenMoulton, Chair ● The MFA programs in Sonic Arts and Media Scoring, Brooklyn College ● Brooklyn College Center for Computer Music (BCCCM) ● H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music ● Professor Maria Conelli, Dean of the S chool of Visual, Media and Performing Arts, Brooklyn College ● The Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, Brooklyn College ● The CERF fund, Brooklyn College 1 Table of Contents Event Page A Short Biography of Pauline Oliveros 3 Symposium Overview 4 Maps and Directions to Event Locations 8 Organizers 10 Concert One Program 11 Program of Talks, Workshop, Panel 14 Concert Two Program 23 Biographies of Participants 27 2 Pauline Oliveros Photo by Paula Court PAULINE OLIVEROS was a senior figure in contemporary American music. Her career spanned over fifty years of boundary dissolving music making. In the '50s she was part of a circle of iconoclastic composers, artists, poets gathered together in San Francisco. Pauline Oliveros' life as a composer, performer and humanitarian was about opening her own and others' sensibilities to the universe and facets of sounds. Since the 1960's she influenced American music profoundly through her work with improvisation, meditation, electronic music, myth and ritual. Pauline Oliveros was the founder of "Deep Listening," which comes from her childhood fascination with sounds and from her works in concert music with composition, improvisation and electroacoustics. Pauline Oliveros described Deep Listening as a way of listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what you are doing. -

Podcast Sounding Places Mini-Series Deep Listening

Podcast Sounding Places Mini-series Deep Listening SHARON STEWART Welcome to this three-part miniseries centered around Deep Listening, the lifework of composer, musician, writer and humanitarian Pauline Oliveros. I’m Sharon Stewart, a creator of sound works, musician, researcher, poet, and Deep Listener. In the first episode “Deep Listening: Pauline Oliveros and the Sonosphere,” I offer facets of my connection to Deep Listening along with some of the history of the practice, as related to the sonic environment – or the sonosphere – with pertinent excerpts from Oliveros’ text scores. Together we can perform a seminal Sonic Meditation, number VIII: Environmental Dialogue. In the second episode “Deep Listening and Reciprocal Listening with Tina Pearson” I draw upon my own scores and the work of Canadian composer, multimedia artist and Deep Listener Tina Pearson, inviting you to contemplate some ways we can involve ourselves in a respectful, listening and playful dialogue with our sonic environment. This interview forms part of my current area of inquiry for the ArtEZ Professorship Theory in the Arts, namely: ethics and ethical practices within artistic research and the creative arts. In the third and final episode “Deep Listening performance scores with Lisa E. Harris,” I ask Deep Listening practitioner, interdisciplinary artist, creative soprano, and composer Lisa E. Harris from Houston Texas to tell us about her connection to Deep Listening and share with us some scores she has written. For those of you who love participatory vocalising,