Sarah Hibberd “Stranded in the Present”. Temporal Expression in Robert Le Diable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

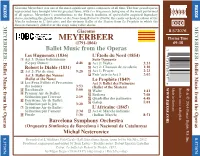

Meyerbeer Was One of the Most Significant Opera Composers of All Time

NAXOS NAXOS Giacomo Meyerbeer was one of the most significant opera composers of all time. The four grand operas represented here brought him his greatest fame, with Les Huguenots being one of the most performed of all operas. Meyerbeer’s contributions to the French tradition of opéra-ballet acquired legendary status, including the ghostly Ballet of the Nuns from Robert le Diable; the exotic orchestral colour of the Marche indienne in L’Africaine; and the virtuoso Ballet of the Skaters from Le Prophète in which the dancers famously glided over the stage using roller skates. DDD MEYERBEER: MEYERBEER: Giacomo 8.573076 MEYERBEER Playing Time (1791-1864) 69:38 Ballet Music from the Operas 7 Les Huguenots (1836) L’Étoile du Nord (1854) 47313 30767 1 Act 3: Danse bohémienne Suite Dansante Ballet Music from the Operas Ballet Music from (Gypsy Dance) 4:46 9 Act 2: Waltz 3:32 the Operas Ballet Music from Robert le Diable (1831) 0 Act 2: Chanson de cavalerie 1:18 2 Act 2: Pas de cinq 9:28 ! Act 1: Prayer 2:23 Act 3: Ballet des Nonnes @ Entr’acte to Act 3 2:02 (Ballet of the Nuns) Le Prophète (1849) 3 Les Feux Follets et Procession Act 3: Ballet des Patineurs 8 des nonnes 3:53 (Ballet of the Skaters) www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 4 Bacchanale 5:00 # Waltz 1:41 & 5 Premier Air de Ballet: $ Redowa 7:08 Ꭿ Séduction par l’ivresse 2:19 % Quadrilles des patineurs 4:48 6 Deuxième Air de Ballet: 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France the Politics of Halevy’S´ La Juive

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France The Politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive Diana R. Hallman published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Diana R. Hallman 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Dante MT 10.75/14 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Hallman, Diana R. Opera, liberalism, and antisemitism in nineteenth-century France: the politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive / by Diana R. Hallman. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in opera) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65086 0 1. Halevy,´ F., 1799–1862. Juive. 2. Opera – France – 19th century. 3. Antisemitism – France – History – 19th century. 4. Liberalism – France – History – 19th century. i. Title. ii. Series. ml410.h17 h35 2002 782.1 –dc21 2001052446 isbn 0 521 65086 0 -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert Le Diable Online

cXKt6 [Get free] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Online [cXKt6.ebook] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Pdf Free Richard Arsenty ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4398313 in Books 2009-03-01Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .50 x 5.70l, .52 #File Name: 1847189644180 pages | File size: 19.Mb Richard Arsenty : The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Liobretto for Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable"By radamesAn excellent publication which contained many stage directions not always reproduced in the nineteenth-century vocal scores and a fine translation. Useful at a time of renewed interest in this opera at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most important and influential opera composers of the nineteenth century, enjoyed a fame during his lifetime hardly rivaled by any of his contemporaries. This eleven volume set provides in one collection all the operatic texts set by Meyerbeer in his career. The texts offer the most complete versions available. Each libretto is translated into modern English by Richard Arsenty; and each work is introduced by Robert Letellier. In this comprehensive edition of Meyerbeer's libretti, the original text and its translation are placed on facing pages for ease of use. About the AuthorRichard Arsenty, a native of the U.S. -

Adolphe Nourrit, La Destinée Romantique D'un Ténor Montpelliérain

Académie des Sciences et Lettres de Montpellier 269 Séance du 13 octobre 2014 Adolphe Nourrit, la destinée romantique d’un ténor montpelliérain par Elysée LOPEZ MOTS-CLÉS Nourrit - Ténor - opéra français - romantisme - rossini. RÉSUMÉ Adolphe Nourrit (1802-1839) natif de montpellier, fit une brillante carrière de ténor à l’Académie royale de musique de Paris, alors installée à l’opéra de la rue le Peletier. Formé par manuel Garcia, ami de son père le ténor louis Nourrit, il s’illustra à partir de 1821 dans les opéras de la fin de la période classique (Gluck)(Moïse et Guillaumedans la création Tell de desRossini, grands La opérasMuette defrançais Portici du d’Auber, début duLa romantismeJuive d’Halévy, Robert le Diable et Les Huguenots de Meyerbeer) . il fit découvrir Schubert en France en chantant ses lieder. Soumis malgré son immense popularité à la concurrence du ténor Delbez, qui le contraint à quitter l’opéra de Paris en 1837, il sombra dans une paranoïa qui l’amena très jeune au suicide en 1839, lors d’un séjour à Naples où il espérait relancer sa carrière. une évocation réaliste des artistes du spectacle vivant – chanteurs lyriques, danseurs, acteurs de théâtre – se heurte à l’absence de toute trace, de tout vestige à même de constituer un témoignage objectif de leur art, du moins jusqu’à l’extrême fin du XiXe et au début du XXe siècle, avec les premiers documents sonores et visuels. Alors même qu’il nous est toujours loisible d’admirer les sculptures attribuées à Praxitèle ou les tableaux exécutés par rembrandt, nous ne pouvons que nous interroger sur la nature du talent de Thepsis, interprète du premier monologue théâtral de la Grèce antique, sur le jeu d’Æsopus, comédien ami de Cicéron, ou, plus près de nous, sur la prestation d’un lekain qui fit pleurer louis Xv, comme sur les accents tragiques du grand Talma, l’acteur favori de Napoléon, ou encore sur la grâce du chant de la malibran, qui ravissait en 1828 le public de l’opéra de Paris. -

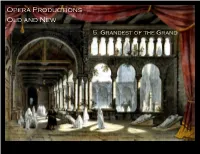

Opera Productions Old and New

Opera Productions Old and New 5. Grandest of the Grand Grand Opera Essentially a French phenomenon of the 1830s through 1850s, although many of its composers were foreign. Large-scale works in five acts (sometimes four), calling for many scene-changes and much theatrical spectacle. Subjects taken from history or historical myth, involving clear moral choices. Highly demanding vocal roles, requiring large ranges, agility, stamina, and power. Orchestra more than accompaniment, painting the scene, or commenting. Substantial use of the chorus, who typically open or close each act. Extended ballet sequences, in the second or third acts. Robert le diable at the Opéra Giacomo Meyerbeer (Jacob Liebmann Beer, 1791–1864) Germany, 1791 Italy, 1816 Paris, 1825 Grand Operas for PAris 1831, Robert le diable 1836, Les Huguenots 1849, Le prophète 1865, L’Africaine Premiere of Le prophète, 1849 The Characters in Robert le Diable ROBERT (tenor), Duke of Normandy, supposedly the offspring of his mother’s liaison with a demon. BERTRAM (bass), Robert’s mentor and friend, but actually his father, in thrall to the Devil. ISABELLE (coloratura soprano), Princess of Sicily, in love with Robert, though committed to marry the winner of an upcoming tournament. ALICE (lyric soprano), Robert’s foster-sister, the moral reference-point of the opera. Courbet: Louis Guéymard as Robert le diable Robert le diable, original design for Act One Robert le diable, Act One (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act Two (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act -

16 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert Le Diable, 1831. the Nuns' Ballet. Meyerbeer's Synesthetic Cocktail Debuts at the Paris Opera

Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert le diable, 1831. The nuns’ ballet. Meyerbeer’s synesthetic cocktail debuts at the Paris Opera. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 16 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 The Prophet and the Pendulum: Sensational Science and Audiovisual Phantasmagoria around 1848 JOHN TRESCH Nothing is more wonderful, nothing more fantastic than actual life. —E.T.A. Hoffmann, “The Sand-Man” (1816) The Fantastic and the Positive During the French Second Republic—the volatile period between the 1848 Revolution and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état—two striking per - formances fired the imaginations of Parisian audiences. The first, in 1849, was a return: after more than a decade, the master of the Parisian grand opera, Giacomo Meyerbeer, launched Le prophète , whose complex instrumentation and astound - ing visuals—including the unprecedented use of electric lighting—surpassed even his own previous innovations in sound and vision. The second, in 1851, was a debut: the installation of Foucault’s pendulum in the Panthéon. The installation marked the first public exposure of one of the most celebrated demonstrations in the history of science. A heavy copper ball suspended from the former cathedral’s copula, once set in motion, swung in a plane that slowly traced a circle on the marble floor, demonstrating the rotation of the earth. In terms of their aim and meaning, these performances might seem polar opposites. -

![ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1791/robert-le-diable-music-by-giacomo-meyerbeer-libretto-by-eug%C3%A8ne-scribe-germain-delavigne-first-performance-op%C3%A9ra-acad%C3%A9mie-royale-paris-november-21-1831-1191791.webp)

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie royale], Paris, November 21, 1831 Robert, son of Bertha, daughter of the Duke of Normandy (who has been seduced by the Devil), wanders to Palermo in Sicily, where he falls in love with the King's daughter, Isabella, and intends to joust in a tournament to win her. His companion, Bertram (in reality his satanic father), forestalls him at every juncture. A compatriot, the minstrel Raimbaut, warns the company about Robert the Devil, and is about to be hanged when Robert's foster sister Alice appears to save him. She has followed Robert with a message from his dead mother; Robert confides to her his love for Isabella, who has banished him because of his jealousy. Alice promises to help and asks in return that she be allowed to marry Raimbaut. When Bertram enters, she recognizes him and hides. Bertram induces Robert to gamble away all his substance. Alice intercedes for Robert with Isabella, who presents him with a new suit of armor to fight the Prince of Granada, but Bertram lures him away from combat, and the Prince wins Isabella. In the cavern of St. Irene, Raimbaut waits for Alice but is tempted by Bertram with money, which he leaves to spend. Alice enters on a scene which betrays Bertram as an unholy spirit, and in spite of clinging to her cross, is about to be destroyed by Bertram when Robert enters. The young man is desperate and ready to resort to magic arts. -

Spontini's Olimpie: Between Tragédie Lyrique and Grand Opéra

Spontini’s Olimpie : between tragédie lyrique and grand opéra Olivier Bara Any study of operatic adaptations of literary works has the merit of draw - ing attention to forgotten titles from the history of opera, illuminated only by the illustrious name of the writer who provided their source. The danger, however, may be twofold. It is easy to lavish excessive attention on some minor work given exaggerated importance by a literary origin of which it is scarcely worthy. Similarly, much credit may be accorded to such-and-such a writer who is supposed – however unwittingly and anachronistically – to have nurtured the Romantic melodramma or the historical grand opéra , simply because those operatic genres have drawn on his or her work. The risk is of creating a double aesthetic confusion, with the source work obscured by the adapted work, which in turn obscures its model. In the case of Olimpie , the tragédie lyrique of Gaspare Spontini, the first danger is averted easily enough: the composer of La Vestale deserves our interest in all his operatic output, even in a work that never enjoyed the expected success in France. There remains the second peril. Olimpie the tragédie lyrique , premiered in its multiple versions between 1819 and 1826, is based on a tragedy by Voltaire dating from 1762. Composed in a period of transition by a figure who had triumphed during the Empire period, it is inspired by a Voltaire play less well known (and less admired) than Zaïre , Sémiramis or Le Fanatisme . Hence Spontini’s work, on which its Voltairean origin sheds but little light, initially seems enigmatic in 59 gaspare spontini: olimpie aesthetic terms: while still faithful to the subjects and forms of the tragédie lyrique , it has the reputation of having blazed the trail for Romantic grand opéra , so that Voltaire might be seen, through a retrospective illusion, as a distant instigator of that genre. -

The Mezzo-Soprano Onstage and Offstage: a Cultural History of the Voice-Type, Singers and Roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918)

The mezzo-soprano onstage and offstage: a cultural history of the voice-type, singers and roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918) Emma Higgins Dissertation submitted to Maynooth University in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Maynooth University Music Department October 2015 Head of Department: Professor Christopher Morris Supervisor: Dr Laura Watson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number SUMMARY 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 LIST OF FIGURES 5 LIST OF TABLES 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER ONE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS A THIRD- 19 REPUBLIC PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN 1.1: Techniques and training 19 1.2: Professional life in the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique 59 CHAPTER TWO: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO ROLE AND ITS 99 RELATIONSHIP WITH THIRD-REPUBLIC SOCIETY 2.1: Bizet’s Carmen and Third-Republic mores 102 2.2: Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila, exoticism, Catholicism and patriotism 132 2.3: Massenet’s Werther, infidelity and maternity 160 CHAPTER THREE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS MUSE 188 3.1: Introduction: the muse/musician concept 188 3.2: Célestine Galli-Marié and Georges Bizet 194 3.3: Marie Delna and Benjamin Godard 221 3.3.1: La Vivandière’s conception and premieres: 1893–95 221 3.3.2: La Vivandière in peace and war: 1895–2013 240 3.4: Lucy Arbell and Jules Massenet 252 3.4.1: Arbell the self-constructed Muse 252 3.4.2: Le procès de Mlle Lucy Arbell – the fight for Cléopâtre and Amadis 268 CONCLUSION 280 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 APPENDICES 305 2 SUMMARY This dissertation discusses the mezzo-soprano singer and her repertoire in the Parisian Opéra and Opéra-Comique companies between 1870 and 1918. -

Lucia Di Lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012

O p e r a B o x Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .9 Reference/Tracking Guide . .10 Lesson Plans . .12 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .44 Flow Charts . .49 Gaetano Donizetti – a biography .............................56 Catalogue of Donizetti’s Operas . .58 Background Notes . .64 Salvadore Cammarano and the Romantic Libretto . .67 World Events in 1835 ....................................73 2011–2012 SEASON History of Opera ........................................76 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .87 così fan tutte WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART The Standard Repertory ...................................91 SEPTEMBER 25 –OCTOBER 2, 2011 Elements of Opera .......................................92 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................96 silent night KEVIN PUTS Glossary of Musical Terms . .101 NOVEMBER 12 – 20, 2011 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .105 werther Evaluation . .108 JULES MASSENET JANUARY 28 –FEBRUARY 5, 2012 Acknowledgements . .109 lucia di lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012 madame butterfly mnopera.org GIACOMO PUCCINI APRIL 14 – 22, 2012 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards.