When Push Comes to Shove: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communication Licence Rent

Communication licences Fact sheet Communication licence rent In November 2018, the NSW Premier had the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART) undertake a review of Rental arrangements for communication towers on Crown land. In November 2019, IPART released its final report to the NSW Government. To provide certainty to tenure holders while the government considers the report, implementation of any changes to the current fee structure will apply from the next renewal or review on or after 1 July 2021. In the interim, all communication tenures on Crown land will be managed under the 2013 IPART fee schedule, or respective existing licence conditions, adjusted by the consumer price index where applicable. In July 2014, the NSW Government adopted all 23 recommendations of the IPART 2013 report, including a rental fee schedule. Visit www.ipart.nsw.gov.au to see the IPART 2013 report. Density classification and rent calculation The annual rent for communication facilities located on a standard site depends on the type of occupation and the location of the facilities. In line with the IPART 2013 report recommendations, NSW is divided into four density classifications, and these determine the annual rent for each site. Table 1 defines these classifications. Annexure A further details the affected local government areas and urban centres and localities (UCLs) of the classifications. Figure 1 shows the location of the classifications. A primary user of a site who owns and maintains the communication infrastructure will incur the rent figures in Table 2. A co-user of a site will be charged rent of 50% that of a primary user. -

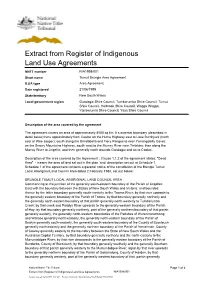

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements NNTT number NIA1998/001 Short name Tumut Brungle Area Agreement ILUA type Area Agreement Date registered 21/06/1999 State/territory New South Wales Local government region Gundagai Shire Council, Tumbarumba Shire Council, Tumut Shire Council, Holbrook Shire Council, Wagga Wagga, Yarrowlumla Shire Council, Yass Shire Council Description of the area covered by the agreement The agreement covers an area of approximately 8500 sq km. It’s external boundary (described in detail below) runs approximately from Coolac on the Hume Highway east to Lake Burrinjuck (north east of Wee Jasper); south along the Brindabella and Fiery Ranges to near Yarrangobilly Caves on the Snowy Mountains Highway, south west to the Murray River near Tintaldra; then along the Murray River to Jingellic; and then generally north towards Gundagai and on to Coolac. Description of the area covered by the Agreement : Clause 1.1.2 of the agreement states: "Deed Area" - means the area of land set out in the plan `and description set out at Schedule 1. Schedule 1 of the agreement contains a gazettal notice of the constitution of the Brungle Tumut Local Aboriginal Land Council Area dated 2 February 1984, set out below: BRUNGLE TUMUT LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL AREA Commencing at the junction of the generally south-eastern boundary of the Parish of Jingellec East with the boundary between the States of New South Wales and Victoria: and bounded thence by the latter boundary generally south-easterly to the Tooma River; by that -

Outback NSW Regional

TO QUILPIE 485km, A THARGOMINDAH 289km B C D E TO CUNNAMULLA 136km F TO CUNNAMULLA 75km G H I J TO ST GEORGE 44km K Source: © DEPARTMENT OF LANDS Nindigully PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 29º00'S Olive Downs 141º00'E 142º00'E www.lands.nsw.gov.au 143º00'E 144º00'E 145º00'E 146º00'E 147º00'E 148º00'E 149º00'E 85 Campground MITCHELL Cameron 61 © Copyright LANDS & Cartoscope Pty Ltd Corner CURRAWINYA Bungunya NAT PK Talwood Dog Fence Dirranbandi (locality) STURT NAT PK Dunwinnie (locality) 0 20 40 60 Boonangar Hungerford Daymar Crossing 405km BRISBANE Kilometres Thallon 75 New QUEENSLAND TO 48km, GOONDIWINDI 80 (locality) 1 Waka England Barringun CULGOA Kunopia 1 Region (locality) FLOODPLAIN 66 NAT PK Boomi Index to adjoining Map Jobs Gate Lake 44 Cartoscope maps Dead Horse 38 Hebel Bokhara Gully Campground CULGOA 19 Tibooburra NAT PK Caloona (locality) 74 Outback Mungindi Dolgelly Mount Wood NSW Map Dubbo River Goodooga Angledool (locality) Bore CORNER 54 Campground Neeworra LEDKNAPPER 40 COUNTRY Region NEW SOUTH WALES (locality) Enngonia NAT RES Weilmoringle STORE Riverina Map 96 Bengerang Check at store for River 122 supply of fuel Region Garah 106 Mungunyah Gundabloui Map (locality) Crossing 44 Milparinka (locality) Fordetail VISIT HISTORIC see Map 11 elec 181 Wanaaring Lednapper Moppin MILPARINKA Lightning Ridge (locality) 79 Crossing Coocoran 103km (locality) 74 Lake 7 Lightning Ridge 30º00'S 76 (locality) Ashley 97 Bore Bath Collymongle 133 TO GOONDIWINDI Birrie (locality) 2 Collerina NARRAN Collarenebri Bullarah 2 (locality) LAKE 36 NOCOLECHE (locality) Salt 71 NAT RES 9 150º00'E NAT RES Pokataroo 38 Lake GWYDIR HWY Grave of 52 MOREE Eliza Kennedy Unsealed roads on 194 (locality) Cumborah 61 Poison Gate Telleraga this map can be difficult (locality) 120km Pincally in wet conditions HWY 82 46 Merrywinebone Swamp 29 Largest Grain (locality) Hollow TO INVERELL 37 98 For detail Silo in Sth. -

Cootamundra and Gundagai 1 Local Government Boundaries Commission

Local Government Boundaries Commission 1. Summary of Local Government Boundaries Commission comments The Boundaries Commission has reviewed the Delegate’s Report on the proposed merger of Cootamundra Shire Council and Gundagai Shire Council to determine whether it shows the legislative process has been followed and the Delegate has taken into account all the factors required under the Local Government Act 1993 (the Act). The Commission has assessed that: the Delegate’s Report shows that the Delegate has undertaken all the processes required by section 263 of the Act, the Delegate’s Report shows that the Delegate has adequately considered all the factors required by section 263(3) of the Act, and the Delegate’s recommendation in relation to the proposed merger is supported by the Delegate’s assessment of the factors. 2. Summary of the merger proposal On 6 January 2016, the Minister for Local Government referred a proposal to merge the local government areas of Cootamundra Shire Council and Gundagai Shire Council to the Acting Chief Executive of the Office of Local Government for examination and report under the Act. The following map shows the proposed new council area (shaded in green). Proposed merger of Cootamundra and Gundagai 1 Local Government Boundaries Commission The proposal would have the following impacts on population across the two councils. Council 2016 2031 Cootamundra Shire Council 7,350 6,600 Gundagai Shire Council 3,700 3,450 New Council 11,050 10,050 Source: NSW Department of Planning & Environment, 2014 NSW Projections (Population, Household and Dwellings). The Acting Chief Executive delegated the function of examining and reporting on each of the proposals to a number of people, known as ‘Delegates’. -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

South Eastern

! ! ! Mount Davies SCA Abercrombie KCR Warragamba-SilverdaleKemps Creek NR Gulguer NR !! South Eastern NSW - Koala Records ! # Burragorang SCA Lea#coc#k #R###P Cobbitty # #### # ! Blue Mountains NP ! ##G#e#org#e#s# #R##iver NP Bendick Murrell NP ### #### Razorback NR Abercrombie River SCA ! ###### ### #### Koorawatha NR Kanangra-Boyd NP Oakdale ! ! ############ # # # Keverstone NPNuggetty SCA William Howe #R####P########## ##### # ! ! ############ ## ## Abercrombie River NP The Oaks ########### # # ### ## Nattai SCA ! ####### # ### ## # Illunie NR ########### # #R#oyal #N#P Dananbilla NR Yerranderie SCA ############### #! Picton ############Hea#thco#t#e NP Gillindich NR Thirlmere #### # ! ! ## Ga!r#awa#rra SCA Bubalahla NR ! #### # Thirlmere Lak!es NP D!#h#a#rawal# SCA # Helensburgh Wiarborough NR ! ##Wilto#n# # ###!#! Young Nattai NP Buxton # !### # # ##! ! Gungewalla NR ! ## # # # Dh#arawal NR Boorowa Thalaba SCA Wombeyan KCR B#a#rgo ## ! Bargo SCA !## ## # Young NR Mares Forest NPWollondilly River NR #!##### I#llawarra Esc#arpment SCA # ## ## # Joadja NR Bargo! Rive##r SC##A##### Y!## ## # ! A ##Y#err#i#nb#ool # !W # #### # GH #C##olo Vale## # Crookwell H I # ### #### Wollongong ! E ###!## ## # # # # Bangadilly NP UM ###! Upper# Ne##pe#an SCA ! H Bow##ral # ## ###### ! # #### Murrumburrah(Harden) Berri#!ma ## ##### ! Back Arm NRTarlo River NPKerrawary NR ## ## Avondale Cecil Ho#skin#s# NR# ! Five Islands NR ILLA ##### !# W ######A#Y AR RA HIGH##W### # Moss# Vale Macquarie Pass NP # ! ! # ! Macquarie Pass SCA Narrangarril NR Bundanoon -

CRJO Board Meeting – Monday 26 October 2020

CRJO Board Meeting – Monday 26 October 2020 CRJO BOARD MEETING Monday, 26 October 2020 10:00am – 12:00pm Zoom Videoconference Meeting ID 920 6506 7728 Our Region… Dynamic Innovative Connected 1 …Compelling! CRJO Board Meeting – Monday 26 October 2020 AGENDA 1. Opening Meeting ............................................................................................................................ 4 2. Welcome & Acknowledgement of Country .................................................................................... 4 3. Apologies ......................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Disclosure of Interest ...................................................................................................................... 4 5. Notice of Rescission ........................................................................................................................ 4 6. Notice of Motions ........................................................................................................................... 4 7. Urgent Business .............................................................................................................................. 4 8. Presentations .................................................................................................................................. 5 8.1. Telstra – Emergency Preparedness ......................................................................................... 5 9. Confirmation -

NSW Department of Local Government

NSW DEPARTME N T OF LOCA NSW DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2006–07 L GOVER N ME N T · ANNU A L REPO R T 2006–07 Our charter To foster a strong and sustainable local government sector that meets changing community needs. Our values As a department we value… l Effective communication—We will consult and collaborate with each other and our stakeholders. l Fairness and equity—We will be open and honest and respectful of those we deal with. l Leadership—We will lead by example and encourage continuous improvement. l People—We will recognise, support and encourage effective working partnerships. l Integrity—We will behave in an ethical manner. About the NSW Department of Local Government The NSW Department of Local Government's role is to provide a policy and legislative framework for the local government sector. We are principally a policy and regulatory agency, acting as a central agency for local government with a key role in managing the relationship between councils and the state government. We are responsible for the overall legal, management and financial framework of the local government sector. Our operating relationships are with state organisations, councils and peak organisations that represent councils and their various constituent interests. This includes the Local Government and Shires Associations (LGSA) which are the main representatives of councils in both political and employer arrangements, as well as the various professional organisations and unions that represent groups of local government employees. 2006–07 focus l Reforming local government l Advising government l Building relationships and communicating effectively l Driving success Operating environment Contents Local government is a $6 billion industry DIRECTOR GENERAL’S FOREWORd 2 in NSW and councils collect $2 billion in FIVE YEAR STATISTICS 4 rates. -

New South Wales Archaeology Pty Ltd ACN 106044366 ______

New South Wales Archaeology Pty Ltd ACN 106044366 __________________________________________________________ Addendum Rye Park Wind Farm Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment Report Date: November 2015 Author: Dr Julie Dibden Proponent: Rye Park Renewables Pty Ltd Local Government Area: Yass Valley, Boorowa, and Upper Lachlan Shire Councils www.nswarchaeology.com.au TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA – BACKGROUND INFORMATION .............................. 7 2.1 THE PHYSICAL SETTING OR LANDSCAPE ........................................................................ 7 2.2 HISTORY OF PEOPLES LIVING ON THE LAND ................................................................ 11 2.3 MATERIAL EVIDENCE ................................................................................................... 17 2.3.1 Previous Environmental Impact Assessment ............................................................ 20 2.3.2 Predictive Model of Aboriginal Site Distribution....................................................... 25 2.3.3 Field Inspection – Methodology ............................................................................... -

Planning Proposal Open and Creative Inner West: Facilitating Extended Trading and Cultural Activities

Inner West Council Planning Proposal Open and Creative Inner West: facilitating extended trading and cultural activities PPAC/2020/0005 Planning Proposal Open and Creative Inner West: facilitating extended trading and cultural activities PPAC/2020/0005 Date: 29 September 2020 Version: 1 PO Box 14, Petersham NSW 2049 Ashfield Service Centre: 260 Liverpool Road, Ashfield NSW 2131 Leichhardt Service Centre: 7-15 Wetherill Street, Leichhardt NSW 2040 Petersham Service Centre: 2-14 Fisher Street, Petersham NSW 2049 ABN 19 488 017 987 Table of contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Background ................................................................................................................................ 2 Part 1 Objectives and intended outcomes ................................................................................... 4 Part 2 Explanation of provisions ................................................................................................. 4 Part 3 Justification .................................................................................................................... 14 Section A – Need for the planning proposal ............................................................................... 14 Section B – Relationship to strategic framework ........................................................................ 17 Section C – Environmental, social and economic impact .......................................................... -

Amalgamations Update

Amalgamations update By publication on the NSW Legislation website at 12.10pm on 12 May 2016 of the Local Government (Council Amalgamations) Proclamation 2016 (2016-242), the Minister for Local Government, exercising power under the Local Government Act 1993, abolished certain existing councils and created 17 new councils as listed below: Armidale Regional Council (Armidale, Dumaresq and Guyra) Canterbury-Bankstown Council (Bankstown and Canterbury) Central Coast Council (Gosford and Wyong) Edward River Council (Conargo and Deniliquin) Federation Council (Corowa and Urana) Georges River Council (Hurstville and Kogarah) Gundagai Council (Cootamundra and Gundagai) Snowy Monaro Regional Council (Bombala, Cooma Monaro and Snowy River) Hilltops Council (Boorowa, Harden and Young) Inner West Council (Ashfield, Leichhardt and Marrickville) Mid-Coast Council (Gloucester, Great Lakes and Greater Taree) Murray River Council (Murray and Wakool) Murrumbidgee Council (Jerilderie and Murrumbidgee) Northern Beaches Council (Manly, Pittwater and Warringah) Queanbeyan-Palerange Regional Council (Queanbeyan and Palerang) Snowy Valleys Council (Tumut and Tumbarumba) Western Plains Regional Council (Dubbo and Wellington) By publication on the NSW Legislation website at 12.10pm on 12 May 2016 of the Local Government (City of Parramatta and Cumberland) Proclamation 2016 (2016-241), the Minister for Local Government, exercising power under the Local Government Act 1993, abolished certain existing councils and created 2 further new councils -

Welcome to the Southern Inland Region

WELCOME TO THE SOUTHERN INLAND REGION HILLTOPS UPPER LACHLAN Young WINGECARRIBEE Taralga Boorowa Crookwell Berrima Bowral MossVale Harden Exeter Binalong Gunning Goulburn Yass Marulan YASS Murrumbateman GOUBURN MULwaREE vaLLEY Gundaroo Sutton Bungendore Queanbeyan Queanbeyan- Braidwood paLERANG Captains Flat Adaminaby Cooma Perisher Berridale Valley Nimmitabel Thredbo Jindabyne Village SNOWY MONARO Bombala Delegate WELCOME TO THE SOUTHERN INLAND REGION CONTENTS ABOUT RDA SOUTHERN INLAND 1 WHO WE ARE 1 OUR REGION 1 OUR CHARTER 2 OUR COMMITTEE 2 OUR STAFF 2 HilltoPS 3 UPPER LACHLAN 6 GOULBURN MULWAREE 10 QUEANBEYAN-Palerang 13 SNOWY MONARO 16 WINGECARRIBEE 19 Yass VALLEY 22 What to DO SOON AFTER ARRIVAL IN AUSTRALIA 24 APPLYING FOR A TAX FILE NUMBER 24 MEDICARE 25 OPENING A BANK ACCOUNT IN AUSTRALIA 26 EMERGENCY SERVICES 28 EMPLOYMENT 31 HOUSING 33 TRANSPORT 34 SCHOOLS 35 MULTICULTURAL SERVICES 36 WELCOME to THE SOUTHERN INLAND REGION ABOUT RDA SOUTHERN INLAND WHO WE ARE Regional Development Australia Southern Inland (RDA Southern Inland) is part of a national network of 52 RDA Committees across Australia. These committees are made up of local leaders who work with all levels of government, business and community groups to support the development of regional Australia. Our aim is to maximise economic development opportunities for the Southern Inland region by attracting new businesses and investment to the region, growing our local business potential and encouraging innovation. RDA Southern Inland is administered by the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities and is an Australian Government initiative. OUR REGION RDA Southern Inland works across a region that takes in seven local government areas in the south-east of NSW, encompassing 44,639 square kilometres of NSW land area.