Bound Together 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame 2001

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME 2001 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Clarence N. Wood Mayor Chair/Commissioner Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues William W. Greaves Laura A. Rissover Director/Community Liaison Chairperson Ó 2001 Hall of Fame Committee. All rights reserved. COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, 3rd Floor Chicago, Illinois 60610 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) Www.GLHallofFame.org 1 2 3 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and our country are made aware of the contributions of Chicago's lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate homophobic bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of people of the LGBT communities, their organizations, and their friends, as well as their contributions to their communities and to the city of Chicago. This is a unique tribute to dedicated individuals and organizations whose services have improved the quality of life for all of Chicago's citizens. -

2009 Program Book

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN GHALLL OHF FAFME 2009 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Dana V. Starks Mayor Chairman and Commissioner Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues William W. Greaves, Ph.D. Director/Community Liaison COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, Suite 300 Chicago, Illinois 60654-3478 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) © 2009 Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame In Memoriam Robert Maddox Tony Midnite 2 3 4 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (now the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, their organizations and their friends, as well as their contributions to the LGBT communities and to the city of Chicago. -

Erotic and Physique Studios Photography Collection, Circa 1930-2005 Coll2014-051

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8br8z8d No online items Finding aid to the erotic and physique studios photography collection, circa 1930-2005 Coll2014-051 Michael C. Oliveira ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California © 2017 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 [email protected] URL: http://one.usc.edu Coll2014-051 1 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Title: Erotic and physique studios photography collection creator: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives Identifier/Call Number: Coll2014-051 Physical Description: 30 Linear Feet37 boxes. Date (inclusive): circa 1930-2005 Abstract: Photographs produced from the 1930s through 2010 by gay erotic or physique photography studios. The studios named in this collection range from short-lived single person operations to larger corporations. Arrangement This collection is divided into two series: (1) Photographic prints and (2) Negatives and slides. Both series are arranged alphabetically. Conditions Governing Access The collection is open to researchers. There are no access restrictions. Conditions Governing Use All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the ONE Archivist. Permission for publication is given on behalf of ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Immediate Source of Acquisition This collection comprises photographs garnered from numerous donations to ONE Archives, many of which are unknown or anonymous. Dan Luckenbill, Neil Edwards, Harold Dittmer, and Dan Raymon are among some of the known donors of photographs in this collection. -

2016 Program Book

2016 INDUCTION CEREMONY Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame Gary G. Chichester Mary F. Morten Co-Chairperson Co-Chairperson Israel Wright Executive Director In Partnership with the CITY OF CHICAGO • COMMISSION ON HUMAN RELATIONS Rahm Emanuel Mona Noriega Mayor Chairman and Commissioner COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST Published by Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame 3712 North Broadway, #637 Chicago, Illinois 60613-4235 773-281-5095 [email protected] ©2016 Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame In Memoriam The Reverend Gregory R. Dell Katherine “Kit” Duffy Adrienne J. Goodman Marie J. Kuda Mary D. Powers 2 3 4 CHICAGO LGBT HALL OF FAME The Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame (formerly the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame) is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, its Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (later the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame (changed to the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 2015) in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. Today, after the advisory council’s abolition and in partnership with the City, the Hall of Fame is in the custody of Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame, an Illinois not- for-profit corporation with a recognized charitable tax-deductible status under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3). -

Chuck Renslow (Fireside Chat) by Doug O'keeffe

Leather Archives & Museum Oral History Interview of Chuck Renslow (Fireside Chat) by Doug O'Keeffe November 15, 2008 Chicago, IL At the Leather Archives & Museum As part of the Fireside Chat program Please note that these transcriptions are unedited. As oral history they represent the speakers' remembrance of past events. Please excuse typos and errors. The original tape recording is part of the collection of the Leather Archive and Museum, Chicago, IL. © Leather Archives & Museum Scope: Chuck Renslow is interviewed before a live studio audience as the second of an ongoing "Inside Leather History," a Fireside chat series produced by the Leather Archives and Museum and the Leather Archives Museum Roadshow. In this interview, Mr. Renslow discusses his family, his relationship with Dom Orejudos, the history of the Gold Coast and other leather bars around the city of Chicago, politics, and how he built and created the Leather Archives and Museum. At the end of the interview the audience has a Q&A with Mr. Renslow. The interview is approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes. (START TAPE) Doug O'Keeffe: (Give everybody a second to get comfortable) Well good evening everyone and welcome to Inside Leather History, a Fireside chat. Tonight's chat is the second in an ongoing series produced by the Leather Archives and Museum, and the Leather Archives and Museum Roadshow. In January Mr. Marcus inaugurated our program. In June next year Mama Sandy Reinhardt (sp?) will be joining us on the stage, and I hope that you'll be able to come and see her. But before I begin I would like to thank all of the volunteers that made this evening possible, I am indebtedly grateful. -

Gay Pioneers: How Drummer Shaped Gay Popular Culture 1965-1999 to History, No Model Identification Documents Or Signed Releases, and No Mail-Order Business

Jack Fritscher Chapter 10 251 CHAPTER 10 THE DRUMMER CURSE: WHY I NEVER BOUGHT DRUMMER • The Drummer Curse of Debt, Disease, and Death: What Happened to People Who Owned Drummer • Leather Heritage: Blacklist Lies Revise Drummer History • 3 Roberts: Mapplethorpe, Opel, and Davolt • John W. Rowberry: Son of Embry, Bane of Barney • Franken-Drummer: Embry Tries to Reanimate the Past in His New Monster of a Magazine: Super MR • Drummer Purpose: Normalizing the Leather Fringe of Gay Culture • Cash and Copyright: Brush Creek Media and Bear Magazine • Cynthia Slater and Frank Sammut: The Catacombs Wedding In 1978, the ninth of our ten years as lovers, David Sparrow loved me enough to give me this advice about Drummer: “Why buy what you already ‘own’?” As the domestic spouse I had married, with leather priest Jim Kane officiat- ing, on the rooftop of 2 Charlton Street in New York, he knew intimately my experiences as editor-in-chief. When I hired him as the freelance and official house-photographer for Drummer, he became his own eyewitness inside Drummer. Considering my fifty-year career in gay writing, people have asked me a hundred times why I never bought Drummer. What was there to buy? Its one-word name was all Drummer had to sell. That, and an insa- tiable deadline that had to be fed every thirty days or the magazine would starve and die. Everything else existed upstairs over a vacant lot. Despite Embry’s dodgy masthead claims, I reckoned there were no legally regis- tered trademarks for sale, no filing cabinets spilling over with a backlog of good stories and photos and drawings panting to be published, no legal paperwork identifying what publishing rights, and republishing rights, had been bought from contributors who were mostly pseudonymous and lost ©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D., All Rights Reserved—posted 03-16-2017 HOW TO LEGALLY QUOTE FROM THIS BOOK 252 Gay Pioneers: How Drummer Shaped Gay Popular Culture 1965-1999 to history, no model identification documents or signed releases, and no mail-order business. -

Ñácate Las Catacumbas Un Templo Del Ojete1

Gayle S. Rubin, Las Catacumbas… ñácate Las Catacumbas Un templo del ojete1 Gayle S. Rubin Traducción: Nahuel Orquera Marcelo Real Cuando escuché por primera vez sobre Las Catacumbas, el nombre me evocó imágenes de las tumbas subterráneas de la antigua Roma, donde los primeros cristianos se refugiaban escapando de la persecución del Estado para practicar su religión, con la mayor reserva posible, de forma clandestina. Las Catacumbas [the Catacombs] de San Francisco fue un local underground similar donde los herejes sexuales del siglo XX pudieron practicar sus propios ritos y rituales de la forma lo más alejada posible de las miradas curiosas u hostiles2. Las Catacumbas tuvo un papel fundamental en la historia de la sexualidad en San Francisco. Siendo una de las “capitales” leather [del inglés, “cuero”] del mundo, San Francisco tuvo en relación con esto un comienzo algo tardío. Los primeros clubes de motociclistas y bares leather gay aparecieron a mediados de los 50 en Nueva York, Los Ángeles y Chicago. El primer bar leather de San Francisco, el Why Not, abrió en 1962 en el barrio de Tenderloin, pero al poco tiempo cerró. El primer bar leather local realmente exitoso a principios de los sesenta, fue el Tool Box: ubicado en la calle 4, número 399, en Harrison, fue también el primer bar leather de San Francisco ubicado en South of Market. San Francisco no había tenido poblaciones3 leather tan numerosas como otras ciudades más grandes de Estados Unidos (Nueva York, Los Ángeles o Chicago), pero una combinación casual de factores a nivel local ‒entre los que se encuentran: tradiciones de libertinaje sexual y tolerancia social, características demográficas de los distritos electorales y la particular economía y fisonomía de ciertos vecindarios‒ contribuyeron a la emergencia en San Francisco de uno de los territorios leather más vastos, diversos y visibles del mundo. -

Gay Pioneers: How Drummer Shaped Gay Popular Culture 1965-1999

Jack Fritscher Chapter 15 365 CHAPTER 15 REQUIRED READING Gender Identity in Drummer A (Descriptive) Masculine Alternative to the (Prescriptive) Sissy Stereotype The Gender War and Homomasculinity • Apartheid and Segregation: Politically Correct LGBT Terrorists Kill Gay Liberation • Are there Leather “Nazis”? Richard Goldstein, “S&M: The Dark Side of Gay Liberation,” Village Voice, July 7, 1975 • Homomasculinity: Philip Nobile, “The Meaning of Gay: An Interview with Dr. C. A. Tripp,” New York Magazine, June 25, 1979: “50% of all young boys eroticize male attributes....90% of homosexuals show no effeminacy.” • Robert Mapplethorpe, Urvashi Vaid, and a Gender Fight for The Advocate cover, “Person of the Year” • Gender Satire: The Red Queen Arthur Evans versus Drummer “Gay men are guardians of the masculine impulse. To have anony- mous sex in a dark alleyway is to pay homage to the dream of male freedom. The unknown stranger is a wandering pagan god. The altar, as in pre-history, is anywhere you kneel.” —Camille Paglia, Sex, Art, and Culture: Essays, “Homosexuality at the Fin de Siecle,” p. 25, Vintage, 1992 During the Titanic 1970s before the iceberg of HIV, I kept on my home desk a copy of the shocking anti-leather feature article that gay journalist, Richard Goldstein, wrote for the Village Voice, July 7, 1975, when Drummer, first published June 20, was only seventeen days old. I was acutely aware of the gay vanilla villains trashing leatherfolk in the separatist gender war of butch and femme. In fact, to bridge the empathy gap ©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D., All Rights Reserved—posted 03-16-2017 HOW TO LEGALLY QUOTE FROM THIS BOOK 366 Gay Pioneers: How Drummer Shaped Gay Popular Culture 1965-1999 between genders, I wrote a reflexive novel on that very theme: Some Dance to Remember: A Memoir-Novel of San Francisco 1970-1982. -

LIL V Program Book

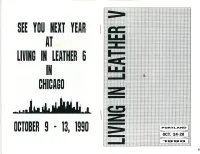

TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information ORGASM Our Name Savs It All! Conference Director: NLA Affrliates SANDMUTOPIA Sallee Huber NLA Chapters SandMutopia CommitteeChair: S and M Utopia George Nelson NLA : Statement of Purpose Suppll'Co. National Co-Chairs: NLA Membership Application ) Jim Richardsi Judy Tallwing McCarthey Special Thanks Electrotorturc Audio Tapes Sounds Magazines N. A. C. Listing Memorial Catl'rctcrs Vicleos Bondage Books Mr. & Ms. NLA: Jan Lyon/ Advertising Leather Drummer Guy Baldwin Latex Mach High Spots: Wayne Gloege CBT DungeonMaster Keynote Speaker: Troy Perry Tit Torture Sandmutopia Guardian Slater/Mains Award: Pat Catifia/ Chuck Renslow Visit us rvhen in San Francisco: - 2{ Shotrvell, San Francisco, CA (.il5) 252-r r95 Workshop Presentors Crcrlit Cartl Orrlers (ihtlly Acccptctl by 'l'clr:¡:lrorre Weekend Schedule C orn pu1=r l'.lodem Usersl Join forces with Local Talent BBS. (41 5) 83i-79=5 l¿r 2l hour access to our catalog. Non.subscribers use 'Drumrn=r' as your password. Workshop Schedule To be on our mailing list, send 53 to: FO Eox 11314, San Franclsco, CA 94101-1314. Art Show Exhibitors CITY: STATE: ZtP Ey ry {ræ bå þçi{ t..eüry rft iEffirt 2l y.rr. ol ¡g.: Mr. & Ms. NLA Contest GENERAL INFORMATION CONFERENCE DIRECTOR As v,e gather in Portla¡xl to celcbrate tiving In læatherV, PHOTOGRAPHY POLICY it seems appropriate toconsider the past, present, and future of what we mean by,,Living In Private photography: Please limit your pictures to peoplesyou know or people who have kåther." As with Ttþs, supersorvls, and other etr'ents given you their permission. -

Author's Foreword

Gay San Francisco: Eyewitness Drummer 83 Foreword by the Author SOME DANCE TO REMEMBER. SOME DON’T. Toward an Autobiography of Drummer Magazine “Of course I have no right whatsoever to write down the truth about my life, involving as it naturally does the lives of so many other people, but I do so urged by a necessity of truth-telling, because there is no living soul who knows the complete truth; here, may be one who knows a section; and, there, one who knows another section; but to the whole picture not one is initi- ated.” — Vita Sackville-West, Portrait of a Marriage LET’S START AT THE VERY BEGINNING . MY ZERO DEGREES OF SEPARATION (MAP INCLUDED) Allegedly. In the vertigo of memory, I write these eyewitness objective notes and subjective opinions allegedly, because I can only analyze events, manu- scripts, and how we people all seemed together, and not the true hearts of persons. As I said to Proust nibbling on his madeleine, “How pungent is the smell of old magazines.” Drummer is the Rosetta Stone of leather heritage. Drummer published its first issue June 1975. What happened next depends on whom you ask. Before history defaults to fable, I choose to write down my oral eye- witness testimony. Readers might try to understand the huge task of writing history that includes the melodrama of one’s own life lived in the first post-Stonewall decade of gay publishing and gay life. The Titanic 1970s were the Gay Belle Epoque of the newly possible. ©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D., All Rights Reserved—posted 05-05-2017 HOW TO LEGALLY QUOTE FROM THIS BOOK 84 Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. -

Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2017 Histories of Consent: Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM Amanda Meltsner University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Meltsner, Amanda, "Histories of Consent: Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM" (2017). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 203. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/203 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Histories of Consent: Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM Amanda Meltsner University of Vermont Honors College 5/1/2017 1 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Methodology 4 Definitions and Descriptions 4 A Brief and Incomplete History of BDSM, With Assorted Add Ons 13 Beginnings 13 Leather: Bars, Clubs, and the Scene 15 Writings and Community 19 The Internet and Kink Community 26 Third Wave Feminism 32 Consent: A History, a Discourse 38 Kink and Consent 40 Origins 42 Academia 50 Feminist Understandings of Consent 53 Comparisons 60 Fifty Shades of Grey: Debates, Connections, and Progress 63 Critiques and Critics 64 Conclusion 78 Acknowledgements 80 References 81 2 Introduction This work aims to explore the conversations and disagreements between pro-kink and anti-kink feminists in the world of feminist writing from the early days of BDSM communities through the publication of Fifty Shades of Grey.