Cybernetics in Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

Interpretação Em Tempo Real Sobre Material Sonoro Pré-Gravado

Interpretação em tempo real sobre material sonoro pré-gravado JOÃO PEDRO MARTINS MEALHA DOS SANTOS Mestrado em Multimédia da Universidade do Porto Dissertação realizada sob a orientação do Professor José Alberto Gomes da Universidade Católica Portuguesa - Escola das Artes Julho de 2014 2 Agradecimentos Em primeiro lugar quero agradecer aos meus pais, por todo o apoio e ajuda desde sempre. Ao orientador José Alberto Gomes, um agradecimento muito especial por toda a paciência e ajuda prestada nesta dissertação. Pelo apoio, incentivo, e ajuda à Sara Esteves, Inês Santos, Manuel Molarinho, Carlos Casaleiro, Luís Salgado e todos os outros amigos que apesar de se encontraram fisicamente ausentes, estão sempre presentes. A todos, muito obrigado! 3 Resumo Esta dissertação tem como foco principal a abordagem à interpretação em tempo real sobre material sonoro pré-gravado, num contexto performativo. Neste caso particular, material sonoro é entendido como música, que consiste numa pulsação regular e definida. O objetivo desta investigação é compreender os diferentes modelos de organização referentes a esse material e, consequentemente, apresentar uma solução em forma de uma aplicação orientada para a performance ao vivo intitulada Reap. Importa referir que o material sonoro utilizado no software aqui apresentado é composto por músicas inteiras, em oposição às pequenas amostras (samples) recorrentes em muitas aplicações já existentes. No desenvolvimento da aplicação foi adotada a análise estatística de descritores aplicada ao material sonoro pré-gravado, de maneira a retirar segmentos que permitem uma nova reorganização da informação sequencial originalmente contida numa música. Através da utilização de controladores de matriz com feedback visual, o arranjo e distribuição destes segmentos são alterados e reorganizados de forma mais simplificada. -

Musique Algorithmique

[Version adaptée pour un cours commun ATIAM/CURSUS d’un article à paraître dans N. Donin and L. Feneyrou (dir.), Théorie de la composition musicale au XXe siècle, Symétrie, 2012] Musique algorithmique Moreno Andreatta . La plupart des études sur la musique algorithmique soulignent, à juste titre, le caractère systématique et combinatoire de certaines démarches compositionnelles qui ont accompagné l’évolution de la musique occidentale. De l’isorythmie du Moyen Âge aux musikalische Würfelspiele ou « jeux musicaux » attribués à Johann Philipp Kirnberger, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Josef Haydn ou Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach, l’utilisation de méthodes combinatoires et algorithmiques n’a pas dû attendre l’« implémentation » informatique pour voir le jour1. Fig 0.1 : « Jeux musicaux » (générés par http://sunsite.univie.ac.at/Mozart/dice/) 1 En attendant un article sur la musique algorithmique dans le Grove Music Online, nous renvoyons le lecteur à l’étude de Karlheinz ESSL, « Algorithmic Composition » (The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music (Nick COLLINS et Julio D’ESCRIVAN, éds.), Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 107-125) pour une analyse plus large des procédés algorithmiques. On pourrait penser, et c’est l’hypothèse le plus souvent proposée, que c’est l’artifice de l’écriture qui rend possible l’exploration de la combinatoire. Cela est sans doute vrai dans plusieurs répertoires, des polyphonies complexes de Philippe de Vitry ou Guillaume de Machaut aux œuvres sérielles intégrales de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Cependant, comme l’ont bien montré certains travaux d’ethnomusicologie et d’ethnomathématique (voir Marc CHEMILLIER, Les Mathématiques naturelles, Paris : Odile Jacob, 2007), l’utilisation d’algorithmes est également présente dans les musiques de tradition orale – une problématique que nous n’aborderons cependant pas ici, car elle dépasse le cadre de cette étude. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

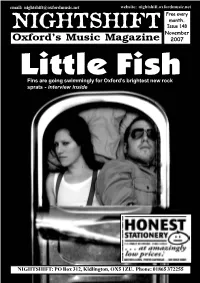

Issue 148.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Selected Organ Works of Joseph Ahrens: a Stylistic Analysis of Freely Composed Works and Serial Compositions

Selected Organ Works of Joseph Ahrens: A Stylistic Analysis of Freely Composed Works and Serial Compositions A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2013 by Eun Hye Kim MM, University of Cincinnati, 2007 MM, Hansei University, 2004 BA, Seoul Jangsin University and Theological Seminary, 2002 Committee Chair: Roberta Gary, DMA Committee Member: John Deaver, DMA Committee Member: David Berry, PhD Abstract Joseph Ahrens (1904–97) was a twentieth-century German composer, virtuoso organist, and teacher. He was a professor of church music at the Berlin Academy of Music (Berlin Hochschule für Musik), organist at the Cathedral of St. Hedwig, and choir director and organist at the Salvator Church in Berlin. He contributed to twentieth-century church music, especially of the Roman Catholic Church, and composed many works for organ and various choral forces. His organ pieces comprise chorale-based pieces, free (non-chorale) works, liturgical pieces, and serial compositions. He was strongly influenced by twentieth-century German music trends such as the organ reform movement, neo-baroque style, and, in his late period, serial techniques. This document examines one freely composed work and two serial compositions by Joseph Ahrens: Canzone in cis (1944), Fantasie und Ricercare (1967), and Trilogia Dodekaphonica (1978). The purpose is to demonstrate that Ahrens’s style developed throughout his career, from a post-Wagnerian harmonic language to one that adopted twentieth-century techniques, including serialism, while retaining the use of developed thematic material and a connection to neo-baroque characteristics in terms of forms and textures. -

The Evolution of the Performer Composer

CONTEMPORARY APPROACHES TO LIVE COMPUTER MUSIC: THE EVOLUTION OF THE PERFORMER COMPOSER BY OWEN SKIPPER VALLIS A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2013 Supervisory Committee Dr. Ajay Kapur (New Zealand School of Music) Supervisor Dr. Dugal McKinnon (New Zealand School of Music) Co-Supervisor © OWEN VALLIS, 2013 NEW ZEALAND SCHOOL OF MUSIC ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines contemporary approaches to live computer music, and the impact they have on the evolution of the composer performer. How do online resources and communities impact the design and creation of new musical interfaces used for live computer music? Can we use machine learning to augment and extend the expressive potential of a single live musician? How can these tools be integrated into ensembles of computer musicians? Given these tools, can we understand the computer musician within the traditional context of acoustic instrumentalists, or do we require new concepts and taxonomies? Lastly, how do audiences perceive and understand these new technologies, and what does this mean for the connection between musician and audience? The focus of the research presented in this dissertation examines the application of current computing technology towards furthering the field of live computer music. This field is diverse and rich, with individual live computer musicians developing custom instruments and unique modes of performance. This diversity leads to the development of new models of performance, and the evolution of established approaches to live instrumental music. This research was conducted in several parts. The first section examines how online communities are iteratively developing interfaces for computer music. -

BOY S GOLD Mver’S Windsong M If for RCA Distribim

Lion, joe f AND REYNOLDS/ BOY S GOLD mver’s Windsong M if For RCA Distribim ARM Rack Jobbe Confab cercise In Commi i cation ista Celebrates 'st Year ith Convention, Concert tal’s Private Stc ijoys 1st Birthd , usexpo Makes I : TED NUGENFS HIGH WIRED ACT. Ted Nugent . Some claim he invented high energy. Audiences across the country agree he does it best. With his music, his songs and his very plugged-in guitar, Ted Nugent’s new album, en- titled “Ted Nugent,” raises the threshold of high energy rock and roll. Ted Nugent. High high volume, high quality. 0n Epic Records and Tapes. High Energy, Zapping Cross-Country On Tour September 18 St. Louis, Missouri; September 19 Chicago, Illinois; September 20 Columbus, Ohio; September 23 Pitts, Penn- sylvania; September 26 Charleston, West Virginia; September 27 Norfolk, Virginia; October 1 Johnson City, Tennessee; Octo- ber 2 Knoxville, Tennessee; October 4 Greensboro, North Carolina; October 5 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; October 8 Louisville, x ‘ Kentucky; October 11 Providence, Rhode Island; October 14 Jonesboro, Arkansas; October 15 Joplin, Missouri; October 17 Lincoln, Nebraska; October 18 Kansas City, Missouri; October 21 Wichita, Kansas; October 24 Tulsa, Oklahoma -j 1 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC-RECORD WEEKLY C4SHBCX VOLUME XXXVII —NUMBER 20 — October 4. 1975 \ |GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW cashbox editorial Executive Vice President Editorial DAVID BUDGE Editor In Chief The Superbullets IAN DOVE East Coast Editorial Director Right now there are a lot of superbullets in the Cash Box Top 1 00 — sure evidence that the summer months are over and the record industry is gearing New York itself for the profitable dash towards the Christmas season. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

Department of Music to Present Concert of Contemporary Italian Music

Department of Music to present concert of contemporary Italian music April 26, 1974 Contemporary Italian music will be presented in a concert Tuesday, May 7, by the Department of Music of the University of California, San Diego. The free concert will be held at 8:15 p.m. in Building 409 on the Matthews campus. Works of young or little known Italian composers will be performed by music faculty and graduate students under the direction of Roberto Laneri. The program will include "Gesti" for piano and "Variazioni su 'Fur Elise' di Beethoven" by Guiseppe Chiari, "Introduzione, Musique de Nuit e Toccata" for clarinet and percussion by Mauro Bortolotti and "Tre Piccoli Pezzi" for flute, oboe and clarinet by Aldo Clementi. Other works will be four songs by Laneri: a selection from "Black Ivory," "George Arvanitis at the Cafe Blue Note - 2:00 a.m. or so," "Per Guiseppe Chiari" and "Imaginary Crossroads #1." The performance will also include "VII" for voice and saxophone by Giacinto Scelsi and "Note e Non" for flute, trombone, violincello, contrabass and percussion by Giancarlo Schiaffini. Chiari, a resident of Florence, is considered a Dada musician. His work is viewed as an expression of revolution by the common people against the repressive division of work in class-oriented societies. Brotolotti and Clementi are composition teachers who helped establish the Nuova Consonanza, a music association for furthering new music in Rome. Their music is transitional between the post-Webern avant-garde style and the work of younger composers. Laneri, a clarinetist and composer, is a Ph.D. -

Thesis Submission

Rebuilding a Culture: Studies in Italian Music after Fascism, 1943-1953 Peter Roderick PhD Music Department of Music, University of York March 2010 Abstract The devastation enacted on the Italian nation by Mussolini’s ventennio and the Second World War had cultural as well as political effects. Combined with the fading careers of the leading generazione dell’ottanta composers (Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero and Ildebrando Pizzetti), it led to a historical moment of perceived crisis and artistic vulnerability within Italian contemporary music. Yet by 1953, dodecaphony had swept the artistic establishment, musical theatre was beginning a renaissance, Italian composers featured prominently at the Darmstadt Ferienkurse , Milan was a pioneering frontier for electronic composition, and contemporary music journals and concerts had become major cultural loci. What happened to effect these monumental stylistic and historical transitions? In addressing this question, this thesis provides a series of studies on music and the politics of musical culture in this ten-year period. It charts Italy’s musical journey from the cultural destruction of the post-war period to its role in the early fifties within the meteoric international rise of the avant-garde artist as institutionally and governmentally-endorsed superman. Integrating stylistic and aesthetic analysis within a historicist framework, its chapters deal with topics such as the collective memory of fascism, internationalism, anti- fascist reaction, the appropriation of serialist aesthetics, the nature of Italian modernism in the ‘aftermath’, the Italian realist/formalist debates, the contradictory politics of musical ‘commitment’, and the growth of a ‘new-music’ culture. In demonstrating how the conflict of the Second World War and its diverse aftermath precipitated a pluralistic and increasingly avant-garde musical society in Italy, this study offers new insights into the transition between pre- and post-war modernist aesthetics and brings musicological focus onto an important but little-studied era.