Mice in the Garden| a Collection of Short-Short (And Short) Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief of Appellee Utah Court of Appeals

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Court of Appeals Briefs 1996 Farmers Insurance Exchange v. David Parker : Brief of Appellee Utah Court of Appeals Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca2 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief Submitted to the Utah Court of Appeals; digitized by the Howard W. Hunter Law Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OCR, may contain errors. Chad B. McKay; Attorney for Appellee. Rodney R. Parker; Snow, Christensen and Martineau; Attorneys for Appellant. Recommended Citation Brief of Appellee, Farmers Insurance Exchange v. Parker, No. 960236 (Utah Court of Appeals, 1996). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca2/173 This Brief of Appellee is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Court of Appeals Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. UTAH COURT OF APPEALS UTAH DOCUMENT KFU 50 DOCKET NO. ^(lOTJe CA IN THE UTAH COURT OF APPEALS FARMERS INSURANCE EXCHANGE Plaintiff/Appellee Case No 960236CA vs. DAVID PARKER Argument Priority 15 Defendant/Appellant. BRIEF OF APPELLEE Appeal from Judgment Rendered By Third Judicial Circuit Court Salt Lake County, State of Utah Honorable Michael L. Hutchings, Presiding CHAD B. McKAY ( 2650 Washington Blvd, #101 Ogden, Utah 84401 Telephone : (801) 621 6021 Attorney for Appellee RODNEY R. -

Word Search Tiffany (Simon) (Dreama) Walker Conflicts Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? February 10 - 16, 2017 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad We’ve got you covered! waxahachietx.com How Grammy V A H A D S D E A M W A H K R performances 2 x 3" ad E Y I L L P A S Q U A L E P D Your Key M A V I A B U X U B A V I E R To Buying L Z W O B Q E N K E H S G W X come together S E C R E T S R V B R I L A Z and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad C N B L J K G C T E W J L F M Carrie Underwood is slated to A D M L U C O X Y X K Y E C K perform at the 59th Annual Grammy Awards Sunday on CBS. R I L K S U P W A C N Q R O M P I R J T I A Y P A V C K N A H A J T I L H E F M U M E F I L W S G C U H F W E B I L L Y K I T S E K I A E R L T M I N S P D F I T X E S O X F J C A S A D I E O Y L L N D B E T N Z K O R Z A N W A L K E R S E “Doubt” on CBS (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Sadie (Ellis) (Katherine) Heigl Lawyers Place your classified Solution on page 13 Albert (Cobb) (Dulé) Hill Justice ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Billy (Brennan) (Steven) Pasquale Secrets Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Cameron (Wirth) (Laverne) Cox Passion Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Tiffany (Simon) (Dreama) Walker Conflicts Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it 2 x 3.5" ad 2 x 4" ad 4 x 4" ad 6 x 3" ad 16 Waxahachie Daily Light homa City Thunder. -

I "I)I WW" the New Orzleans Review

.\,- - i 1' i 1 i "I)i WW" the new orzleans Review LOYOLA UNIVERSITY A Iournal of Literature Vol. 5, No.2 & Culture Published by Loyola University table of contents of the South New Orleans articles Thomas Merton: Language and Silence/Brooke Hopkins .... Editor: $ Jesus and Jujubes/Roger Gillis . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Marcus Smith I v fiction Managing Editor: Tom Bell The Nuclear Family Man and His Earth Mother Wife Come to Grips with the Situation/Otto R. Salassi .... .. .... .. .. .... .. .. Associate Editors: The Harvesters/Martha Bennett Stiles .. .. .. ... .. ....... Peter Cangelosi Beautiful Women and Glorious Medals/Barbara de la Cuesta .. Iohn Christman Dawson Gaillard interviews Lee Gary Link in the Chain of Feeling/An Interview with Anais Nin . .. .. .. Shael Herman A Missionary of Sorts/An Interview with Rosemary Daniell . .. .. I‘. HID BLISS ' 0 QQI{Q photography Advisory Editsrs= Portfolio/Ed Metz .. .... ..... ..... ..... .... ... ... ... David Daiches $'4 >' liZ‘1iiPéZ‘§Zy P°°"Y Joseph Frrhrerr Sf I Why is it that children/Brooke Hopkins ..... ... .. .. ... .. .. A_ $_]_ . .. ... .. .. .. Ioseph Tetlowr $ { ‘ Definition of God/R. P. Lawry . .. ..... .. .. The Unknown Sailor/Miller Williams .... .. .. ... .. ........ .. Editor-at-Large: .. .. $ ' For Fred Carpenter Who Died in His Sleep/Miller Williams . Alexis Gonzales, F.S.C. ' ‘ There Was a Man Made Ninety Million Dollars/Miller Williams .. ' For Victor Jara/Miller Williams ... .. .... ... ........ .... ... ... .. Ed‘r‘r%"?1 ."‘SSg°‘§‘e= ' An Old Man Writing/Shelley Ehrlich ...... .. .. ..... ... .. ... .. $ rlstina g en v Poem/Everette Maddox . .... .. .... .. ..... .. .. .. ... ... .. Th O 1 R . b_ . .. .. ... ... .. ’Q {.' Publication/Everette Maddox . .... ....... .... 1r§hI:r(muarrr(:r‘:{1rfbr?‘£1r(;r:ri§ %L:rr_ Tlck Tock/Everette Maddox .... .. .............. .. .. .. .. ... versityr New Orleans { .. .. .. ...... ... ...... ... ........ .. .. ... l ' $ ’ In Praise of Even Plastic/John Stone Subscription rate: $1.50 per 0 Bringing Her Home/John Stone ... -

POETRY in SPEECH a Volume in the Series

POETRY IN SPEECH A volume in the series MYTH AND POETICS edited by GREGORY NAGY A fu lllist of tides in the series appears at the end of the book. POETRY IN SPEECH Orality and Homeric Discourse EGBERT J. BAKKER CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1997 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850, or visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 1997 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bakker, Egbert J. Poetry in speech : orality and Homeric discourse / Egbert J. Bakker. p. cm. — (Myth and poetics) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-0-8014-3295-8 (cloth) — ISBN-13: 978-1-5017-2276-9 (pbk.) 1. Homer—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Epic poetry, Greek—History and criticism. 3. Discourse analysis, Literary. 4. Oral formulaic analysis. 5. Oral tradition—Greece. 6. Speech in literature. 7. Poetics. I. Title. PA4037.B33 1996 883'.01—dc20 96-31979 The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Contents Foreword, by Gregory Nagy -

The Will to Believe, and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy

The Will to Believe, and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy Written by William James Edited & Published by 1 Publisher’s Notes This edition is a derivative work of ―The Will to Believe, and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy”, written by William James. William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist who was also trained as a physician. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, James was one of the leading thinkers of the late nineteenth century and is believed by many to be one of the most influential philosophers the United States has ever produced, while others have labelled him the "Father of American psychology". PDFBooksWorld’s eBook editors have carefully edited the electronic version of this book with the goal of restoring author’s original work. Please let us know if we made any errors. We can be contacted at our website by email through this contact us page link. Original content of this eBook is available in public domain and it is edited and published by us under a creative commons license (available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Source: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/26659.txt.utf-8 Copyright rules and laws for accessing public domain contents vary from country to country. Be sure to check whether this book is in public domain in the country you are located. This link may help you to find the public domain status of this eBook in your country. This eBook is free for non commercial purpose only, and can be downloaded for personal use from our website at http://www.pdfbooksworld.com. -

Court of Claims

STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA REPORT OF THE COURT OF CLAIMS For the Period from July 1, 2003 to June 30, 2005 by CHERYLE M. HALL CLERK Volume XXV (Published by authority W.Va. Code § 14-2-25) ------------------------ Š ------------------------ THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK ------------------------ Š ------------------------ W.Va.] CONTENTS III TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Letter of transmittal . VI Opinions of the Court.......................................... VIX Personnel of the Court ......................................... IV Former judges .......................................... V References - Court of Claims ................................... 238 Table of Cases Reported - Court of Claims ......................... X Terms of Court ............................................... VII IV PERSONNEL OF THE STATE COURT OF CLAIMS [W.Va PERSONNEL OF THE STATE COURT OF CLAIMS HONORABLE DAVID M. BAKER ....................... Presiding Judge HONORABLE BENJAMIN HAYS WEBB, II . Judge HONORABLE FRANKLIN L. GRITT, JR. ........................ Judge HONORABLE ROBERT B. SAYRE ....................... Interim Judge HONORABLE GEORGE F. FORDHAM ........................... Judge CHERYLE M. HALL .......................................... Clerk DARRELL V. MCGRAW, JR. ......................... Attorney General W.Va.] FORMER JUDGES V FORMER JUDGES ___________________ HONORABLE JULIUS W. SINGLETON, JR. July 1, 1967 to July 31, 1968 HONORABLE A. W. PETROPLUS . August 1, 1968 to June 30, 1974 HONORABLE HENRY LAKIN DUCKER . July 1, 1967 to October 31, 1975 HONORABLE W. LYLE JONES .......................... July 1,1974 to June 30, 1976 HONORABLE JOHN B. GARDEN ........................ July 1,1974 to December 31, 1982 HONORABLE DANIEL A. RULEY, JR. July 1, 1976 to February 28, 1983 HONORABLE GEORGE S. WALLACE, JR. February 2, 1976 to June 30, 1989 HONORABLE JAMES C. LYONS . February 17, 1983 to June 30, 1985 HONORABLE WILLIAM W. GRACEY . May 19, 1983 to December 23, 1989 HONORABLE DAVID G. HANLON . August 18, 1986 to December 31, 1992 HONORABLE ROBERT M. -

Analysis of Rockfall Hazards

Analysis of rockfall hazards Introduction Rockfalls are a major hazard in rock cuts for highways and railways in mountainous terrain. While rockfalls do not pose the same level of economic risk as large scale failures which can and do close major transportation routes for days at a time, the number of people killed by rockfalls tends to be of the same order as people killed by all other forms of rock slope instability. Badger and Lowell (1992) summarised the experience of the Washington State Department of Highways. They stated that ‘A significant number of accidents and nearly a half dozen fatalities have occurred because of rockfalls in the last 30 years … [and] … 45 percent of all unstable slope problems are rock fall related’. Hungr and Evans (1989) note that, in Canada, there have been 13 rockfall deaths in the past 87 years. Almost all of these deaths have been on the mountain highways of British Columbia. Figure 1: A rock slope on a mountain highway. Rockfalls are a major hazard on such highways Analysis of rockfall hazards Figure 2: Construction on an active roadway, which is sometimes necessary when there is absolutely no alternative access, increases the rockfall hazard many times over that for slopes without construction or for situations in which the road can be closed during construction. Mechanics of rockfalls Rockfalls are generally initiated by some climatic or biological event that causes a change in the forces acting on a rock. These events may include pore pressure increases due to rainfall infiltration, erosion of surrounding material during heavy rain storms, freeze-thaw processes in cold climates, chemical degradation or weathering of the rock, root growth or leverage by roots moving in high winds. -

In Mr. Knox's Country

In Mr. Knox's Country By Martin Ross IN MR. KNOX'S COUNTRY I THE AUSSOLAS MARTIN CAT Flurry Knox and I had driven some fourteen miles to a tryst with one David Courtney, of Fanaghy. But, at the appointed cross-roads, David Courtney was not. It was a gleaming morning in mid-May, when everything was young and tense and thin and fit to run for its life, like a Derby horse. Above us was such of the spacious bare country as we had not already climbed, with nothing on it taller than a thorn-bush from one end of it to the other. The hill-top blazed with yellow furze, and great silver balls of cloud looked over its edge. Nearly as white were the little white-washed houses that were tucked in and out of the grey rocks on the hill-side. "It's up there somewhere he lives," said Flurry, turning his cart across the road; "which'll you do, hold the horse or go look for him?" I said I would go to look for him. I mounted the hill by a wandering bohireen resembling nothing so much as a series of bony elbows; a white-washed cottage presently confronted me, clinging, like a sea-anemone, to a rock. I knocked at the closed door, I tapped at a window held up by a great, speckled foreign shell, but without success. Climbing another elbow, I repeated the process at two successive houses, but without avail. All was as deserted as Pompeii, and, as at Pompeii, the live rock in the road was worn smooth by feet and scarred with wheel tracks. -

The GAVIN REPORT

ISSUE 1565 JULY 12, 1985 the GAVIN REPORT 4 1 Z LUQ P INSIDE STORY: SAWYER BROWN TONY RICHLAND'S HOLLYWOOD AND MORE! ONE HALLIDIE PLAZA, SUITE :25, SAN FRANCISCO CALIFORNIA 94102 415392.7750 www.americanradiohistory.com By lar demand, the sta ing- room -only smash on thei first U.S. tour, DO YOU WANT CRYING is the next hit ' w -_ www.americanradiohistory.com the GAVIN REPOT T Editor: Dave Sholin _ ©1 4. 3. 1. PAUL YOUNG - Every Time You Go Away (Columbia) 2. 1. 2. Prince - Raspberry Beret (Warner Brothers) 3. 2. 3. Duran Duran - A View To A Kill (Capitol) 6. 5. 4. Madonna - Into The Groove (Sire /Warner Brothers) &M) 13. 6. 5. STING - If You Love Somebody Set Them Free (A PHIL COLLINS 11. 8. 6. BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN - Glory Days (Columbia) Don't Lose My Number 24. 15. 7. TEARS FOR FEARS - Shout (Mercury /PolyGram) (Atlantic) 12. 9. 8. WHITNEY HOUSTON You Give Good Love (Arista) 160 Adds 20. 12. 9. COREY HART - Never Surrender (EMI /America) 1. 4. 10. Phil Collins - Sussudio (Atlantic) BILLY JOEL 9. 7. 11. 'Til Tuesday - Voices Carry (Epic) Of Love (Chrysalis) You're Only Human 28. 20. 12. HUEY LEWIS & THE NEWS - The Power (Columbia) 15. 14. 13. NIGHT RANGER - Sentimental Street (Camel /MCA) Now 93 Adds 19. 16. 14. DEBARGE - Who's Holding Donna (Gordy) 15. Survivor - The Search Is Over (Scotti Brothers) 5. 10. Brothers) POINTER SISTERS 25. 22. 16. DEPECHE MODE - People Are People (Sire /Warner A (Capitol) Dare Me 23. 19. 17. POWER STATION - Get It On (Bang Gong) (RCA) 33. -

1878-03-231.Pdf

VOL. VIII. r_ __ .__ gg DOVER, MORRIS COUNTY. NEW JERSEY, SATURDAY, MARCH 23, 1878. 15 TH E1R0NER liuslittss Cards. POETIC. Red to the woods foi mounted oil n horse which bad beei ninrlvrs of frredora wore gathered t< "Heal is L.r«-r«M In Dcoilt." ?VIlLlXUtt> 2.TKVJ BXTVBVAI11 VEGETINE! Tom Quick, concealment from their bloodja»«ilanU.: taken from a farmer of Winieiuk. Tin gel bur, nnd, with all tliu Ecr*AT v-'lii Then: i;, no t'ruj.tei- fnllacy tbun tlio It. A. BEMVE'i'T, M. D , £,Vu.J BKNJ. H.'VOGT. TUE wfiile the little girls stood by tho slaiu savage fell upon the neck of the horse, Bttzutla eloquence," BI:«3 tho jwmp .liuinn Imld by many, partlcahtrly tho HOMCEOPATHI body of tbuir tcucher bewilderud am military and civic diupbiy, dupusitcd EDITOR *!ti> 1'ttOBlETOlL Purifies the Blood, Reno- but managed to keep his. scat ia the sad- young ami Htroug und vigorous, that horror struck, urjt knowing their awi dle nntil he had readied the opposite tbe burying ground at Oosheu. A. mc-i •inter, espcd'ully n sharp, ti-QRtj cue, Office on Morris Sfcreot near Blackwell. PUVSlCIAiS&SmtOEOBT INDIAN SLAYER vates and Invigorates fate, whether death or captivity. Will itod tbonglj long delayed token of respoi Cor. 'Bltckwell &' Warren Sts. AND THE bank, and joined tocli of his friends an with plenty of BUOW—is tlie most heal- Tennis 09 SUBSCRIPTION the Whole System. gray, they wcreutauding in this pitiful oocdi bad crossed before him. It ii said that for tlie ashes cf the dead, whose coutiii Ihy season of tbe year. -

Dragon Magazine #197

Issue #197 Vol. XVIII, No. 4 FEATURES September 1993 10 The Ecology of the Giant Scorpion Ruth Cooke Publisher Think invisibility will save you? Think again. James M. Ward 15 Think Bigin Miniature! James M. Ward Editor If a miniature could come to life, Ral Partha would be Roger E. Moore the company to make it. Associate editor Two Years of ORIGINS Awards The editors Dale A. Donovan 18 Is your game one of the best? Two years worth of awards will let you know. Fiction editor Barbara G. Young Perils & Postage Mark R. Kehl 24How to play an AD&D® campaign when each player Editorial assistant Wolfgang H. Baur lives in a different city. Art director By Mail or by Modem? Craig Schaefer Larry W. Smith 30 An AD&D game works just as well by BBS as by USPS (and maybe better). Production staff Tracey Zamagne The Dragons Bestiary Ed Greenwood 34 Its not a petting zoo: four new monsters from the Subscriptions Janet L. Winters FORGOTTEN REALMS® setting. The Known World Grimoire Bruce A. Heard U.S. advertising Cindy Rick 41 The world of Mystara is changing, but how? Turn to page 41 to find out. U.K. correspondent and U.K. advertising Join the Electronic Warriors! James M. Ward Wendy Mottaz 67Whats in the works for computer gamers from the team of SSI and TSR. The MARVEL®-Phile Steven E. Schend 80 Its a dirty world in the streetsbut your heros there to clean it up. DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is published tion throughout the United Kingdom is by Comag monthly by TSR, Inc., P.O. -

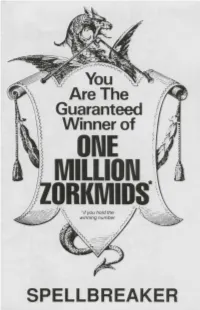

Fantasycoll-Spellbreaker-Map

SPELLBREAKER Just when things seem at their worst, you might find yourself the lucky winner of a fabulous prize in our all-new " Map Your Future" ••••••••• Sweepstakes! GRAND PRIZE: Sweepstakes Instructions Using tl1€ enclosed map . fill in the blanks in the following state ments. Only entry forms with completed statements will be eligi One Million Zorkmids ble . Mail your entry form to : .. Map Your Future " Sweepstakes . to spend however you like! Frobou Magic Magic Equipment Company. Borphee . 1. You 'll need to use your Frobozz Magic Magic Equipment Com- 2 FIRST PRIZES: • pany luminstone to avoid being eaten in the ____ Ga....e . • Live like a king in the castle of your dreams! We'll build to your speci • 2. You might want to sow some Frobozz Magic Magic Equipment • fications - anything you want up to 100,000 zorkmids! • Company magnetic bozberry seeds in the ______ . 3. The carpets sold at the ________ cannot match • • the strength and reliabiility of those offered by the Frobozz Magic • • Magic Equipment Company. • 4. The _______ is the perfect place to show off your • Frobozz Magic Magic Equipment Company flame-resistant alche • • mist's jumpsuit. • • 5. There is _______ like home, unless it is the Frobozz • Magic Magic Equipment Company outlet store in Borphee, open 7 • days a week, dawn to dusk . • • Please Send Me: • • D LUMINSTONE.Frotz spell on the blink? Our luminstone emits a purple glow to • • light your way. Keep it in your pocket for those unexpectedly Dark moments . Zm15 . • • D BOZBERRY SEEDS. Having trouble maintaining a protective circle? Magnetic • • bozbeyry leaves draw evil forces out of your home and into the bozberry root, • whe ~ they are rendered harmless .