Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Cinema WL 3390/CTV 3390 No Prerequisites. in English

Italian Cinema WL 3390/CTV 3390 No prerequisites. In English. SYLLABUS Brandy Alvarez [email protected] 416 Clements Hall Tel. 214 768 1892 Required texts: Peter Bondanella, Italian Cinema from Noerealism to the Present ; Continuum, New York, 1997 (Third Edition 2001) and course packet Grading: 25 % class discussion 25 % daily response papers 25 % oral presentation 25 % final paper Methods of evaluation : Students will write short responses to each film (generally one page to a page and a half) and answer analytical questions that are distributed with each film, present to the class a summary of a critical film essay, and write a five-page final paper on one of the film's we viewed in class. Absences: Given the nature of the J-term course, any absence will affect the final grade (one grade for each absence). Student Learning Outcomes: (from Creativity and Aesthetics: Level One : 1). Students will be able to identify methods, techniques, or languages of a particular art form and explain how those inform its creation, performance, or analysis, and 2. Students will be able to demonstrate an understanding of concepts fundamental to the creative impulse through analysis. Overview and additional learning expectations : This course offers a brief chronological survey of renowned Italian films and directors as well as exemplars of popular cinema that enjoyed box office success abroad. We will explore the themes and cinematic style of Neorealism and the 'generational' waves of those directors who followed in its wake, including Fellini. Students will watch the films in original language with English subtitles. • Students learn the fundamentals of film analysis, including the basic structural and narrative components of a film, and the terminology necessary to describe both. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

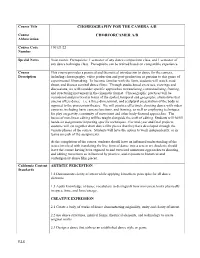

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

The Myth of the Good Italian in the Italian Cinema

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 16 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy July 2014 The Myth of the Good Italian in the Italian Cinema Sanja Bogojević Faculty of Philosophy, University of Montenegro Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n16p675 Abstract In this paper we analyze the phenomenon called the “myth of the good Italian” in the Italian cinema, especially in the first three decades of after-war period. Thanks to the recent success of films such as Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds or Academy Award- winning Benigni’s film La vita è bella and Spielberg’s Schindler’s List it is commonly believed that the Holocaust is a very frequent and popular theme. Nevertheless, this statement is only partly true, especially when it comes to Italian cinema. Soon after the atrocities of the WWII Italian cinema became one of the most prominent and influential thanks to its national film movement, neorealism, characterized by stories set amongst the poor and famished postwar Italy, celebrating the fight for freedom under the banners of Resistance and representing a nation opposed to the Fascist and Nazi regime. Interestingly, these films, in spite of their very important social engagement, didn’t even mention the Holocaust or its victims and it wasn’t until the 1960’s that Italian cinema focused on representing and telling this horrific stories. Nevertheless, these films represented Italians as innocent and incapable of committing cruel acts. The responsibility is usually transferred to the Germans as typically cold and sadistic, absolving Italians of their individual and national guilt. -

Des Films Suggérés

Des films suggérés Films animés -Persepolis (bio d’une fille iranienne) Films comiques -L’Auberge espagnole (int’l college student roommates) Science Fiction/Fantaisie -Les poupées russes (sequel) -City of Lost Children -Les compères (who’s the real father?) -Delicatessen -3 hommes & un couffin (original of 3 Men & a baby) -Le placard (The Closet—man pretends to be gay) Films Spirituels / Réligieux -La chèvre -Thérèse (story of Ste Thérèse) -Les visiteurs (medieval knights travel to future) -Jésus de Montréal (Passion play turns real) -anything with Fernandel (noir & blanc) -My wife is an Actress (husband jealous of wife’s costars) Films dramatiques -Dîner des cons (Who’s really the jerk?) -Camille Claudel (true tragic story of great artist) -Mon oncle (weird comedy, not much talking) -Toto le héros (man’s whole life consumed by jealousy) -Jean de Florette* (city man moves to inherited farm w/family) Comédies romantiques -Manon des sources* (sequel, concentrates on daughter ) -Après vous (man helps down & out friend) -A Self-Made Hero (insecure guy totally invents life & army career) -Maman, il y a un homme dans ton lit! -Le Huitième Jour (friendship between 2 guys, 1 handicapped, 1 sad) -Amélie (girl finds amazing ways to right wrongs!) -Bleu (woman makes new life after tragic car accident) -Paper wedding (Green Card en français) -Blanc -The Valet (car parker pretends to be girl’s copain) -Rouge (romantic meetings--coincidence or destiny?) -A la mode (rags to riches story) -Est-Oeust (family returns to Russia w/ horrible consequences) -

Delegates Guide

Delegates Guide 9–14 March, 2018 Cultural Partners Supported by Friends of Qumra Media Partner QUMRA DELEGATES GUIDE Qumra Programming Team 5 Qumra Masters 7 Master Class Moderators 14 Qumra Project Delegates 17 Industry Delegates 57 QUMRA PROGRAMMING TEAM Fatma Al Remaihi CEO, Doha Film Institute Director, Qumra Jaser Alagha Aya Al-Blouchi Quay Chu Anthea Devotta Qumra Industry Qumra Master Classes Development Qumra Industry Senior Coordinator Senior Coordinator Executive Coordinator Youth Programmes Senior Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Senior Coordinator Elia Suleiman Artistic Advisor, Doha Film Institute Mayar Hamdan Yassmine Hammoudi Karem Kamel Maryam Essa Al Khulaifi Qumra Shorts Coordinator Qumra Production Qumra Talks Senior Qumra Pass Senior Development Assistant Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Film Programming Senior QFF Programme Manager Hanaa Issa Coordinator Animation Producer Director of Strategy and Development Deputy Director, Qumra Meriem Mesraoua Vanessa Paradis Nina Rodriguez Alanoud Al Saiari Grants Senior Coordinator Grants Coordinator Qumra Industry Senior Qumra Pass Coordinator Coordinator Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Wesam Said Eliza Subotowicz Rawda Al-Thani Jana Wehbe Grants Assistant Grants Senior Coordinator Film Programming Qumra Industry Senior Assistant Coordinator Khalil Benkirane Ali Khechen Jovan Marjanović Chadi Zeneddine Head of Grants Qumra Industry Industry Advisor Film Programmer Ania Wojtowicz Manager Qumra Shorts Coordinator Film Training Senior Film Workshops & Labs Senior Coordinator -

New Bfi Filmography Reveals Complete Story of Uk Film

NEW BFI FILMOGRAPHY REVEALS COMPLETE STORY OF UK FILM 1911 – 2017 filmography.bfi.org.uk | #BFIFilmography • New findings about women in UK feature film – percentage of women cast unchanged in over 100 years and less than 1% of films identified as having a majority female crew • Queen Victoria, Sherlock Holmes and James Bond most featured characters • Judi Dench is now the most prolific working female actor with the release of Victoria and Abdul this month • Michael Caine is the most prolific working actor • Kate Dickie revealed as the most credited female film actor of the current decade followed by Jodie Whittaker, the first female Doctor Who • Jim Broadbent is the most credited actor of the current decade • Brits make more films about war than sex, and more about Europe than Great Britain • MAN is the most common word in film titles • Gurinder Chadha and Sally Potter are the most prolific working female film directors and Ken Loach is the most prolific male London, Wednesday 20 September 2017 – Today the BFI launched the BFI Filmography, the world’s first complete and accurate living record of UK cinema that means everyone – from film fans and industry professionals to researchers and students – can now search and explore British film history, for free. A treasure trove of new information, the BFI Filmography is an ever-expanding record that draws on credits from over 10,000 films, from the first UK film released in cinemas in 1911 through to present day, and charts the 250,000 cast and crew behind them. There are 130 genres within the BFI Filmography, the largest of which is Drama with 3,710 films. -

Annual Report, FY 2013

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2013 Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 CONTENTS Letter from the Librarian of Congress ......................... 5 Organizational Reports ............................................... 47 Organization Chart ............................................... 48 Library of Congress Officers ........................................ 6 Congressional Research Service ............................ 50 Library of Congress Committees ................................. 7 U.S. Copyright Office ............................................ 52 Office of the Librarian .......................................... 54 Facts at a Glance ......................................................... 10 Law Library ........................................................... 56 Library Services .................................................... 58 Mission Statement. ...................................................... 11 Office of Strategic Initiatives ................................. 60 Serving the Congress................................................... 12 Office of Support Operations ............................... 62 Legislative Support ................................................ 13 Office of the Inspector General ............................ 63 Copyright Matters ................................................. 14 Copyright Royalty Board ..................................... -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Selected Academic Bibliography Career Overviews

Updated: August 2015 Sally Potter: Selected Academic Bibliography Career Overviews: Books The second, longer annotation for each of these books is quoted from: Lucy BOLTON, “Catherine Fowler, Sally Potter and Sophie Mayer, The Cinema of Sally Potter” [review] Screen 51:3 (2010), pp. 285-289. Please cite any quotation from Bolton’s review appropriately. Catherine FOWLER, Sally Potter (Contemporary Film Directors series). Chicago: University of Illinois, 2009. Fowler’s book offers an extended and detailed reading of Potter’s early performance work and Expanded Cinema events, staking a bold claim for reading the later features through the lens of the Expanded Cinema project, with its emphasis on performativity, liveness, and the deconstruction of classical asymmetric and gendered relations both on-screen and between screen and audience. Fowler offers both a career overview and a sustained close reading of individual films with particular awareness of camera movement, space, and performance as they shape the narrative opportunities that Potter newly imagines for her female characters. “By entitling the section on Potter’s evolution as a ‘Search for a “frame of her own”’, Fowler situates the director firmly in a feminist tradition. For Fowler, Potter’s films explore the tension for women between creativity and company, and Potter’s onscreen observers become ‘surrogate Sallys’ in this regard (p. 25). Fowler describes how Potter’s films engage with theory and criticism, as she deconstructs and troubles the gaze with her ‘ambivalent camera’ (p. 28), the movement of which is ‘designed to make seeing difficult’ (p. 193). For Fowler, Potter’s films have at their heart the desire to free women from the narrative conventions of patriarchal cinema, having an editing style and mise- en-scene that never objectifies or fetishizes women; rather, Fowler argues, Potter’s women are free to explore female friendships and different power relationships, uncoupled, as it were, from narratives that prescribe heterosexual union. -

Umass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall

umassumass finefine artsarts center center CENTERCENTER SERIESSERIES 2008–20092008–2009 1 1 2 3 2 3 playbill playbill 1 Paul Taylor Dance Company 11/13/08 2 Avery Sharpe Trio 11/21/08 3 Soweto Gospel Choir 12/03/08 1 Paul Taylor Dance Company 11/13/08 2 Avery Sharpe Trio 11/21/08 3 Soweto Gospel Choir 12/03/08 UMA021-PlaybillCover.indd 3 8/6/08 11:03:54 PM UMA021-PlaybillCover.indd 3 8/6/08 11:03:54 PM DtCokeYoga8.5x11.qxp 5/17/07 11:30 AM Page 1 DC-07-M-3214 Yoga Class 8.5” x 11” YOGA CLASS ©2007The Coca-Cola Company. Diet Coke and the Dynamic Ribbon are registered trademarks The of Coca-Cola Company. 2 We’ve mastered the fine art of health care. Whether you need a family doctor or a physician specialist, in our region it’s Baystate Medical Practices that takes center stage in providing quality and excellence. From Greenfield to East Longmeadow, from young children to seniors, from coughs and colds to highly sophisticated surgery — we’ve got the talent and experience it takes to be the best. Visit us at www.baystatehealth.com/bmp 3 &ALLON¬#OMMUNITY¬(EALTH¬0LAN IS¬PROUD¬TO¬SPONSOR¬THE 5-ASS¬&RIENDS¬OF¬THE¬&INE¬!RTS¬#ENTER 4 5 Supporting The Community We Live In Helps Create a Better World For All Of Us Allen Davis, CFP® and The Davis Group Are Proud Supporters of the Fine Arts Center! The work we do with our clients enables them to share their assets with their families, loved ones, and the causes they support. -

Download Detailseite

Panorama/IFB 2005 YES Whereas at one time he removed shrapnel from bodies, sewed up wounds Filmografie and saved lives, he now finds himself cutting up dead animals for a lavish 1979 THRILLER dinner. Nevertheless, his memories of war in the Middle East persist to this Kurzfilm YES 1983 THE GOLD DIGGERS YES day. These memories soon become their common ground – for her knowl- Kurzfilm Regie: Sally Potter edge of religious conflict in Northern Ireland means that she too is no 1986 THE LONDON STORY stranger to civil war. He lives the life of an exile in a tiny apartment – far TEARS, LAUGHTER, FEARS AND away from his culture, his family and his home. Although her surroundings RAGE may be a good deal more luxurious than his, she too lives a kind of private TV-Dokumentarserie 1988 I AM AN OX, I AM A HORSE, I AM Großbritannien/USA 2004 Darsteller exile, alone and lonely. A MAN, I AM A WOMAN Frau Joan Allen A passionate affair ensues; but all too soon their love affair is overshadowed Dokumentarfilm Länge 95 Min. Mann Simon Abkarian by events in the world at large. The religion he believed to have left behind 1992 ORLANDO (ORLANDO) Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Anthony Sam Neill along with the world he was forced to renounce years ago, begins to take 1997 THE TANGO LESSON Farbe Putzfrau Shirley Henderson on an importance that even outweighs his need for sex and love. (TANGO LESSON) Tante Sheila Hancock 2000 THE MAN WHO CRIED Stabliste Kate Samantha Bond (IN STÜRMISCHEN ZEITEN) Buch Sally Potter Grace Stephanie Leonidas YES 2004 YES Kamera Alexei Rodionov Billy Gary Lewis C’est une Américaine originaire d’Irlande du Nord.