Perpetual Motion Electronic Mediations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Tion on the Internet. but Convincing Fans to Actually Buy Their Music Is

FEBRUARY 2005 OK Go records its While on tour in Toronto with the Kaiser Chiefs, the members of OK Go- second album, lead singer/guitarist Damian Kulash, bassist Tim Nordwind, drummer Dan "Oh No," in Malmö, Konopka and guitar/keyboard player Andy Ross -give a video copy of a Sweden, with dance routine for the song "A Million Ways" from their new album to a fan. Tore Johansson. They had teamed with Kulash's sister Trish Sie, a former professional ballroom dancer, to choreograph the number and intended to perform the dance at the end of live shows. In mid -May, the band had filmed one of the rehearsal sessions in the backyard of Kulash's Los Angeles home. OCTOBER 25 2005 The "A Million . Ways" video is featured on VH1's "Best Week Ever" as online views top 1 million. A week later, the band and a Running handful of its fans perform the dance on The band performs "A Million Ways" on "The Tonight Show With Jay "Good Morning Leno," kicking off a media blitz in connection with the album release America," and "A in which they next do the song Sept. 9 on "Mad TV." But despite the Million Ways" tops surging viewership for "A Million Ways," the video is never formally MTVu's countdown Start submitted to MTV or VH1. "We never got a giant push from them to show "The OK Go Jogs Some Serious Digital Sales On Back Of Web Buzz BY BRIAN GARRITY play it. There was just all this hoopla around the Internet activity," says Dean's List." Rick Krim, executive VP of music and talent for VH1. -

Morgan Unt:Il Furt:Her St:Udy

.. ' :n··' ~' .. ar . Volume XXVI. Number 25 Law S.tudent-s Board ·Votes N;ot to Elect . ' -- ·Proffer Blood Morgan To Ill Teaeher Unt:il Furt:her St:udy . In the. only contested publication position, Robert S. Gallimore last night Forty Men . From was voted by the Publications Board editor of OLD GOLD AND BLACK for Law School and the year of 194~:43. He defeated Herbert Thompson, the only other candidate Sports V ohmteer to take the positiOn. ' Forty law students and three j · For T~e Student, co1le~e magazine, no ~~itor was elected. Neil Morgan, football players vol'!lllteered ·to present editor, was~a candidate for the positiOn, but the election was postponed •. - have their blood tested for trans-. indefinitely- until it can be establishe~ constitutionally whether or not an editor ,fusion this week when it was - can succeed himself. The present~------------=-=- 'learned t~at P11ofess()r I. B.. Lake . 1constitution of the Publications -uf the law school faculty, now on I ~card ~as be~n lost, and the elec- leave of absence for national de- · 1t10n will await the drafting of a Debaters Take ..-f:ense work in connection with the 'new document. Office of Production Management For all other student publication First Places in Washington, is seriously ill, in , Ipositions only one candidate for Durham's Duke, Hospital with an each had filed application, and infection of the blood stream · In Tournament ,, each was elected with no dissen- ,• which as yet remains a mystery to sion by the Publications Board. Hope, Bell and attending physicians. ' , . New editor of the Howler is Ed- Davi's w· Of the 43 men volunteering, 16 I Yiin Wilson. -

University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's Theses UARC.0666

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8833tht No online items Finding Aid for the University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses UARC.0666 Finding aid prepared by University Archives staff, 1998 June; revised by Katharine A. Lawrie; 2013 October. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 August 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections UARC.0666 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses Creator: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Identifier/Call Number: UARC.0666 Physical Description: 30 Linear Feet(30 cartons) Date (inclusive): 1958-1994 Abstract: Record Series 666 contains Master's theses generated within the UCLA Dance Department between 1958 and 1988. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Copyright of portions of this collection has been assigned to The Regents of the University of California. The UCLA University Archives can grant permission to publish for materials to which it holds the copyright. All requests for permission to publish or quote must be submitted in writing to the UCLA University Archivist. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses (University Archives Record Series 666). UCLA Library Special Collections, University Archives, University of California, Los Angeles. -

The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: a Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2018 The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries Rachel Smith University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Rachel, "The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries" (2018). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers 1 The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: A Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries Rachel Smith Departmental Honors Thesis University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Health and Human Performance Examination Date: March 22, 2018 ________________________________ ______________________________ Shewanee Howard-Baptiste Burch Oglesby Associate Professor of Exercise Science Associate Professor of Exercise Science Thesis Director Department Examiner ________________________________ Liz Hathaway Assistant Professor of Exercise -

Fact Or Fiction: Hollywood Looks at the News

FACT OR FICTION: HOLLYWOOD LOOKS AT THE NEWS Loren Ghiglione Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University Joe Saltzman Director of the IJPC, associate dean, and professor of journalism USC Annenberg School for Communication Curators “Hollywood Looks at the News: the Image of the Journalist in Film and Television” exhibit Newseum, Washington D.C. 2005 “Listen to me. Print that story, you’re a dead man.” “It’s not just me anymore. You’d have to stop every newspaper in the country now and you’re not big enough for that job. People like you have tried it before with bullets, prison, censorship. As long as even one newspaper will print the truth, you’re finished.” “Hey, Hutcheson, that noise, what’s that racket?” “That’s the press, baby. The press. And there’s nothing you can do about it. Nothing.” Mobster threatening Hutcheson, managing editor of the Day and the editor’s response in Deadline U.S.A. (1952) “You left the camera and you went to help him…why didn’t you take the camera if you were going to be so humane?” “…because I can’t hold a camera and help somebody at the same time. “Yes, and by not having your camera, you lost footage that nobody else would have had. You see, you have to make a decision whether you are going to be part of the story or whether you’re going to be there to record the story.” Max Brackett, veteran television reporter, to neophyte producer-technician Laurie in Mad City (1997) An editor risks his life to expose crime and print the truth. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Boris Pasternak - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Boris Pasternak - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Boris Pasternak(10 February 1890 - 30 May 1960) Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was a Russian language poet, novelist, and literary translator. In his native Russia, Pasternak's anthology My Sister Life, is one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Furthermore, Pasternak's theatrical translations of Goethe, Schiller, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, and William Shakespeare remain deeply popular with Russian audiences. Outside Russia, Pasternak is best known for authoring Doctor Zhivago, a novel which spans the last years of Czarist Russia and the earliest days of the Soviet Union. Banned in the USSR, Doctor Zhivago was smuggled to Milan and published in 1957. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year, an event which both humiliated and enraged the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the midst of a massive campaign against him by both the KGB and the Union of Soviet Writers, Pasternak reluctantly agreed to decline the Prize. In his resignation letter to the Nobel Committee, Pasternak stated the reaction of the Soviet State was the only reason for his decision. By the time of his death from lung cancer in 1960, the campaign against Pasternak had severely damaged the international credibility of the U.S.S.R. He remains a major figure in Russian literature to this day. Furthermore, tactics pioneered by Pasternak were later continued, expanded, and refined by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and other Soviet dissidents. <b>Early Life</b> Pasternak was born in Moscow on 10 February, (Gregorian), 1890 (Julian 29 January) into a wealthy Russian Jewish family which had been received into the Russian Orthodox Church. -

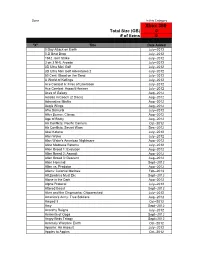

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

1993 Shrine of Mary Revitalized

St. Norbert Times Volume 89 Issue 2 Article 1 9-19-2017 1993 Shrine of Mary Revitalized Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/snctimes Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Music Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Photography Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Technical and Professional Writing Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation (2017) "1993 Shrine of Mary Revitalized," St. Norbert Times: Vol. 89 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/snctimes/vol89/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Norbert Times by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. September 19, 2017 Volume 89 | Issue 2 | Serving our Community without Fear or Favor since 1929 INDEX: NEWS: 1993 Shrine of Mary Revitalized Old Doors, New ELYNOR GREGORICH | NEWS CORRESPONDENT Look SEE PAGE 2 > OPINION: Your Voice Goes Beyond Voting SEE PAGE 4 > FEATURES: A Letter from the Editors SEE PAGE 10> ENTERTAINMENT: Comeback Albums SEE PAGE 12 > SPORTS: SNC Soccer Updates The path leading into what will be the Kunkel Meditation Garden The site of the future Calawerts Family Grotto of Our Lady | SEE PAGE 14 > | Elynor Gregorich Elynor Gregorich Happy Fall, The life of the 25-year- the Virgin Mary, framed by a The original statue and Times that “We’re a Catholic old Shrine of Mary on the wooden surround and set in arbor were in place by the institution, but really have no Y’all! northeastern end of campus a circular pathway lined with end of September in 1992 place for contemplation and Fall officially be- is renewed this year by sig- benches. -

Television & New Media

Television & New Media http://tvn.sagepub.com/ Here We Go Again: Music Videos after YouTube Maura Edmond Television New Media 2014 15: 305 originally published online 27 November 2012 DOI: 10.1177/1527476412465901 The online version of this article can be found at: http://tvn.sagepub.com/content/15/4/305 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Television & New Media can be found at: Email Alerts: http://tvn.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://tvn.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://tvn.sagepub.com/content/15/4/305.refs.html >> Version of Record - Apr 8, 2014 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Nov 27, 2012 What is This? Downloaded from tvn.sagepub.com at JAMES MADISON UNIV on September 16, 2014 TVN15410.1177/1527476412 465901Television & New MediaEdmond Article Television & New Media 2014, Vol. 15(4) 305 –320 Here We Go Again: Music © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permissions: Videos after YouTube sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1527476412465901 tvn.sagepub.com Maura Edmond1 Abstract At the start of the 2000s, there were dire predictions about the future of music videos. Faced with falling industry profits, ballooning production costs, and music television stations that cared more about ratings, music videos no longer enjoyed the industry support they once had. But as music videos were being sidelined by the music and television industries, they were rapidly becoming integral to online video aggregates and social media sites. The “days of the $600,000 video” might be gone, but in recent years, a new music video culture and economy has emerged. -

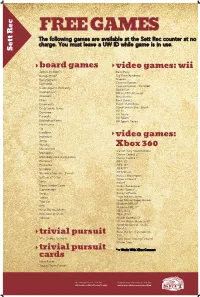

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm.