Investigating the Diet of Mesolithic Groups in the Southern Alps: an Attempt Using Stable Carbon and Nitrogen Isotope Analyses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promozione Promozione Trentino Alto Adige

TRENTINO 3 Giovedì 22 agosto 2019 CALENDARI CALCIO REGIONALE Promozione Promozione Trentino Alto Adige 1 Set. 2019 1ª Giornata 9 Feb. 2020 8 Set. 2019 2ª Giornata 16 Feb. 2020 15 Set. 2019 3ª Giornata 23 Feb. 2020 1 Set. 2019 1ª Giornata 16 Feb. 2020 8 Set. 2019 2ª Giornata 23 Feb. 2020 15 Set. 2019 3ª Giornata 1 Mar. 2020 CALCIOCHIESE - MEZZOCORONA GARDOLO - BORGO AQUILA TRENTO - CALCIOCHIESE VALLE AURINA - PARCINES RAIFF. BRUNICO - VALLE AURINA VALLE AURINA - VAL PASSIRIA AQUILA TRENTO - ALENSE NAGO TORBOLE - CAVEDINE LASINO BORGO - ROVERETO ALBES - BRUNICO CAMPO TRENS - STRADA D. VINO SUD ALBES - APPIANO PINZOLO V. RENDENA - BORGO CALCIOCHIESE - TELVE VOLANO - RAVINENSE NATURNO - VORAN LEIFERS APPIANO - NAZ NAZ - CAMPO TRENS VOLANO - NAGO TORBOLE ALENSE - VOLANO BASSA ANAUNIA - GARDOLO NAZ - VAL PASSIRIA LACES - NATURNO PARCINES RAIFF. - BRUNICO BENACENSE - BASSA ANAUNIA PINZOLO V. RENDENA - BASSA ANAUNIA CAVEDINE LASINO - ALENSE SCENA - CAMPO TRENS MILLAND - SCENA SCENA - VORAN LEIFERS CAVEDINE LASINO - ROVERETO MEZZOCORONA - BENACENSE PINZOLO V. RENDENA - BENACENSE STEGONA - MILLAND PARCINES RAIFF. - TERLANO STEGONA - LACES SACCO S.GIORGIO - GARDOLO ROVERETO - SACCO S.GIORGIO SACCO S.GIORGIO - NAGO TORBOLE TERLANO - LACES VAL PASSIRIA - ALBES TERLANO - NATURNO TELVE - RAVINENSE RAVINENSE - AQUILA TRENTO TELVE - MEZZOCORONA STRADA D. VINO SUD - APPIANO VORAN LEIFERS - STEGONA STRADA D. VINO SUD - MILLAND 22 Set. 2019 4ª Giornata 1 Mar. 2020 29 Set. 2019 5ª Giornata 8 Mar. 2020 6 Ott. 2019 6ª Giornata 15 Mar. 2020 18 Set. 2019 4ª Giornata 8 Mar. 2020 22 Set. 2019 5ª Giornata 15 Mar. 2020 29 Set. 2019 6ª Giornata 22 Mar. 2020 GARDOLO - PINZOLO V. RENDENA GARDOLO - BENACENSE MEZZOCORONA - CAVEDINE LASINO BRUNICO - TERLANO VALLE AURINA - CAMPO TRENS CAMPO TRENS - PARCINES RAIFF. -

Emerald Cycling Trails

CYCLING GUIDE Austria Italia Slovenia W M W O W .C . A BI RI Emerald KE-ALPEAD Cycling Trails GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE 3 Content Emerald Cycling Trails Circular cycling route Only few cycling destinations provide I. 1 Tolmin–Nova Gorica 4 such a diverse landscape on such a small area. Combined with the turbulent history I. 2 Gorizia–Cividale del Friuli 6 and hospitality of the local population, I. 3 Cividale del Friuli–Tolmin 8 this destination provides ideal conditions for wonderful cycling holidays. Travelling by bicycle gives you a chance to experi- Connecting tours ence different landscapes every day since II. 1 Kolovrat 10 you may start your tour in the very heart II. 2 Dobrovo–Castelmonte 11 of the Julian Alps and end it by the Adriatic Sea. Alpine region with steep mountains, deep valleys and wonderful emerald rivers like the emerald II. 3 Around Kanin 12 beauty Soča (Isonzo), mountain ridges and western slopes which slowly II. 4 Breginjski kot 14 descend into the lowland of the Natisone (Nadiža) Valleys on one side, II. 5 Čepovan valley & Trnovo forest 15 and the numerous plateaus with splendid views or vineyards of Brda, Collio and the Colli Orientali del Friuli region on the other. Cycling tours Familiarization tours are routed across the Slovenian and Italian territory and allow cyclists to III. 1 Tribil Superiore in Natisone valleys 16 try and compare typical Slovenian and Italian dishes and wines in the same day, or to visit wonderful historical cities like Cividale del Friuli which III. 2 Bovec 17 was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. -

BCT1 (Fondo Miscellaneo). Archivi Di Famiglie 2018

BCT1 (Fondo miscellaneo). Archivi di famiglie 2018 AGOSTINI COLLOCAZIONE: BCT1–3088/16, BCT1–3088/29 ESTREMI CRONOLOGICI: 1754-1773 DATA DI ACQUISIZIONE E PROVENIENZA: i documenti collocati al ms. BCT1–3088 sono stati donati da Pietro Zanolini nell’anno 1908 e fanno parte di una raccolta di 43 documenti, relativi a diverse famiglie trentine, rilegati in due volumi. DESCRIZIONE: 1. Contratti di compravendita - 1754 aprile 28, Leonardo Segata di Sopramonte vende a Valentino Agostini di quel luogo un prato ubicato nelle pertinenze di Sopramonte: BCT1–3088/16 - 1773 maggio 20, Contratto di permuta concluso tra Gianantonio Rosat di Sopramonte e Antonio Agostini del medesimo luogo: BCT1–3088/29 ALBERTINI COLLOCAZIONE: BCT2 ESTREMI CRONOLOGICI:1590 DATA DI ACQUISIZIONE E PROVENIENZA: Hippoliti, famiglia DESCRIZIONE: 1. Contratti - 1590 febbraio 10, Maria fu Tomeo Pazzo da Cinte, vedova di Pellegrino Alde da Scurelle e Zaneto suo figlio vendono a Nicolò Albertino una pezza di terra sita a Scurelle, in luogo det- to ‘a Pra de Ponte’: BCT2–884 ALESSANDRINI DI NEUENSTEIN COLLOCAZIONE: BCT1–482, BCT1–905, BCT1–1038, BCT1–2409, BCT2 DATA DI ACQUISIZIONE E PROVENIENZA: raccolta Mazzetti e altre provenienze fondo manoscritti BCT1–1696, BCT1–1818, BCT1–2224, BCT1–2518, BCT1–2668, vedi anche BCT2 DESCRIZIONE: - De anatome humani corporis, auctore Julio Alexandrino cum notis, copia del sec. XVII: BCT1–2409 ALIPRANDI COLLOCAZIONE: BCT1–1188 ESTREMI CRONOLOGICI:1654 DATA DI ACQUISIZIONE E PROVENIENZA: Raccolta Antonio Mazzetti DESCRIZIONE: 1. Privilegi di nobiltà - 1654: BCT1–1188 ALMERICO 1 BCT1 (Fondo miscellaneo). Archivi di famiglie dicembre 2014 COLLOCAZIONE: BCT1–2478 ESTREMI CRONOLOGICI:1820 DESCRIZIONE: 1. Eredità - 1820, Pretesa Mazani sull’eredità di famiglia: BCT1–2478 ALTENBURGER COLLOCAZIONE: BCT1–3322 ESTREMI CRONOLOGICI:1733 DATA DI ACQUISIZIONE E PROVENIENZA: Lascito Tranquillini dell’aprile 1923, pervenuta con i docu- menti della famiglia Valentini di Calliano e della famiglia Zambaiti di Vezzano. -

The Schio-Vicenza Fault System (NE Italy)

https://doi.org/10.5194/se-2021-29 Preprint. Discussion started: 22 April 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Geodynamic and seismotectonic model of a long-lived transverse structure: The Schio-Vicenza Fault System (NE Italy) Dario Zampieri1, Paola Vannoli2, Pierfrancesco Burrato2 1Dipartimento di Geoscienze, Università degli Studi di Padova, Padova, Italy 5 2Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione Roma 1, Rome, Italy Correspondence to: Pierfrancesco Burrato ([email protected]) Abstract. We make a thorough review of geological and seismological data on the long-lived Schio-Vicenza Fault System (SVFS) in northern Italy and present for it a geodynamic and seismotectonic interpretation. The SVFS is a major and high angle structure transverse to the mean trend of the Eastern Southern Alps fold-and-thrust belt, 10 and the knowledge of this structure is deeply rooted in the geological literature and spans for more than a century and a half. The main fault of the SVFS is the Schio-Vicenza Fault (SVF), which has a significant imprint in the landscape across the Eastern Southern Alps and the Veneto-Friuli foreland. The SVF can be divided into a northern segment, extending into the chain north of Schio and mapped up to the Adige Valley, and a southern one, coinciding with the SVF proper. The latter segment borders to the east the Lessini, Berici Mts. and Euganei Hills block, separating this foreland structural high from the 15 Veneto-Friuli foreland, and continues southeastward beneath the recent sediments of the plain via the blind Conselve-Pomposa fault. The structures forming the SVFS have been active with different tectonic phases and different style of faulting at least since the Mesozoic, with a long-term dip-slip component of faulting well defined and, on the contrary, the horizontal component of the movement not well constrained. -

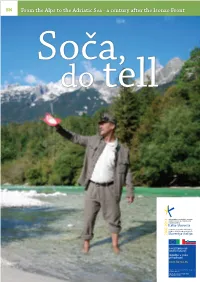

From the Alps to the Adriatic

EN From the Alps to the Adriatic Sea - a century after the Isonzo Front Soča, do tell “Alone alone alone I have to be in eternity self and self in eternity discover my lumnious feathers into afar space release and peace from beyond land in self grip.” Srečko Kosovel Dear travellers Have you ever embraced the Alps and the Adriatic with by the Walk of Peace from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea that a single view? Have you ever strolled along the emerald runs across green and diverse landscape – past picturesque Soča River from its lively source in Triglav National Park towns, out-of-the-way villages and open fireplaces where to its indolent mouth in the nature reserve in the Bay of good stories abound. Trieste? Experience the bonds that link Italy and Slove- nia on the Walk of Peace. Spend a weekend with a knowledgeable guide, by yourself or in a group and see the sites by car, on foot or by bicycle. This is where the Great War cut fiercely into serenity a century Tourism experience providers have come together in the T- ago. Upon the centenary of the Isonzo Front, we remember lab cross-border network and together created new ideas for the hundreds of thousands of men and boys in the trenches your short break, all of which can be found in the brochure and on ramparts that they built with their own hands. Did entitled Soča, Do Tell. you know that their courageous wives who worked in the rear sometimes packed clothing in the large grenades instead of Welcome to the Walk of Peace! Feel the boundless experi- explosives as a way of resistance? ences and freedom, spread your wings among the vistas of the mountains and the sea, let yourself be pampered by the Today, the historic heritage of European importance is linked hospitality of the locals. -

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 13 November 2015 English only Economic Commission for Europe Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes Seventh session Budapest, 17–19 November 2015 Item 4(i) of the provisional agenda Draft assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin Assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin* Prepared by the secretariat with the Royal Institute of Technology Summary At its sixth session (Rome, 28–30 November 2012), the Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes requested the Task Force on the Water-Food-Energy-Ecosystems Nexus, in cooperation with the Working Group on Integrated Water Resources Management, to prepare a thematic assessment focusing on the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus for the seventh session of the Meeting of the Parties (see ECE/MP.WAT/37, para. 38 (i)). The present document contains the scoping-level nexus assessment of the Isonzo/Soča River Basin with a focus on the downstream part of the basin. The document is the result of an assessment process carried out according to the methodology described in publication ECE/MP.WAT/46, developed on the basis of a desk study of relevant documentation, an assessment workshop (Gorizia, Italy; 26-27 May 2015), as well as inputs from local experts and officials of Italy. Updates in the process were reported at the meetings of the Task Force. -

Thomas RAINER, Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER, Gerd RANTITSCH, Uroš HERLEC & Marko VRABEC

Austrian Journal of Earth Sciences Volume 102/2 Vienna 2009 Organic maturity trends across the Variscan discordance in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone (Slovenia, Austria, Italy): Variscan versus Alpidic thermal overprint_________ Thomas RAINER1)3)*), Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER1), Gerd RANTITSCH1), Uroš HERLEC2) & Marko VRABEC2) 1) KEYWORDS Mining University Leoben, Department for Applied Geosciences and Geophysics, 8700 Leoben, Austria; 2) University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, Department of Geology, Vitrinite reflectance Variscan Discordance 2) Aškerčeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; Northern Dinarides 3) Present Address: OMV Exploration & Production GmbH, Trabrennstrasse 6-8, 1020 Wien, Austria; Southern Alps Carboniferous *) Corresponding author, [email protected] Eastern Alps Abstract In the Southern Alps and the northern Dinarides the main Variscan deformation event occurred during Late Carboniferous (Bashki- rian to Moscovian) time. It is represented locally by an angular unconformitiy, the “Variscan discordance”, separating the pre-Variscan basement from the post-Variscan (Moscovian to Cenozoic) sedimentary cover. The main aim of the present contribution is to inves- tigate whether a Variscan thermal overprint can be detected and distinguished from an Alpine thermal overprint due to Permo-Meso- zoic basin subsidence in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone in Slovenia. Vitrinite reflectance (VR) is used as a temperature sensitive parameter to determine the thermal overprint of pre- and post-Variscan sedimentary successions in the eastern part of the Southern Alps (Carnic Alps, South Karawanken Range, Paški Kozjak, Konjiška Gora) and in the northern Dinarides (Sava Folds, Trnovo Nappe). Neither in the eastern part of the Southern Alps, nor in the northern Dinarides a break in coalification can be recognized across the “Variscan discordance”. -

Tectonics of the Dolomites

Tectonics of the Dolomites Autor(en): Doglioni, Carlo Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Bulletin für angewandte Geologie Band (Jahr): 12 (2007) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 26.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-226374 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Bull, angew. Geol. Vol. 12/2 Dezember 2007 S.11-15 Tectonics of the Dolomites Carlo Doglioni1 Keywords: Southern Alps, thrust belt, Mesozoic tectonics, Alpine tectonics The Dolomites are a part of the Alps, and The Mesozoic extension is particularly therefore they recorded the subduction evident already from the general geologic map history of this orogeny (e. -

Serie D1 Maschile Calendario 2020 Gironi

FEDERAZIONE ITALIANA TENNIS TN SERIE D1 MASCHILE 2020 SERIE D1 MASCHILE - Girone 1 SQUADRA CAMPI PALLE SEDE DI GIOCO Dunlop Fort All Court CT PREDAZZO Terra rossa Tournament Select VIA RODODENDRI, Predazzo 38037 (TN) CT BORGO Terra rossa Dunlop Australian Open PIAZZA AL MERCATO, Borgo Valsugana 38051 (TN) Dunlop Fort All Court CT MEZZOCORONA Terra rossa Tournament Select VIA SOTTODOSSI, Mezzocorona 38016 (TN) Dunlop Fort All Court CT TRENTO B Terra rossa Tournament Select PIAZZA VENEZIA, Trento 38122 (TN) Dunlop Fort All Court AT DARZO Sintetico - Play-it Tournament Select VIA CAPITELLO - DARZO, Storo 38089 (TN) CT ARGENTARIO Terra rossa Wilson US Open VIA DEI COLLI PARCO URBANO, Lavis 38015 (TN) CLASSIFICA CALENDARIO RIS. PEN. squadra g v n p pen. i.v. P domenica 5 luglio 2020 CT ARGENTARIO 5 5 0 0 0 19 10 09:00 CT PREDAZZO - CT TRENTO B 2 2 0 0 CT MEZZOCORONA 5 3 1 1 0 12 7 09:00 CT MEZZOCORONA - AT DARZO 3 1 0 0 CT PREDAZZO 5 2 2 1 0 10 6 09:00 CT ARGENTARIO - CT BORGO 4 0 0 0 CT TRENTO B 5 1 2 2 0 7 4 domenica 12 luglio 2020 AT DARZO 5 1 0 4 0 7 2 09:00 AT DARZO - CT TRENTO B 1 3 0 0 CT BORGO 5 0 1 4 0 5 1 09:00 CT MEZZOCORONA - CT ARGENTARIO 0 4 0 0 09:00 CT BORGO - CT PREDAZZO 1 3 0 0 domenica 19 luglio 2020 09:00 CT TRENTO B - CT MEZZOCORONA 0 4 0 0 09:00 CT PREDAZZO - CT ARGENTARIO 0 4 0 0 09:00 AT DARZO - CT BORGO 3 1 0 0 domenica 26 luglio 2020 09:00 CT ARGENTARIO - CT TRENTO B 4 0 0 0 09:00 CT BORGO - CT MEZZOCORONA 1 3 0 0 09:00 CT PREDAZZO - AT DARZO 3 1 0 0 domenica 2 agosto 2020 09:00 CT TRENTO B - CT BORGO 2 2 0 0 09:00 CT MEZZOCORONA - CT PREDAZZO 2 2 0 0 09:00 AT DARZO - CT ARGENTARIO 1 3 0 0 CT MEZZOCORONA - AT DARZO ROSINI CLAUDIO FESTA MATTIA 63 63 PANCHERI MASSIMO FONTANA NICOLA 61 40 RIT. -

Why Didn't You Take Advantage of the Chance to Disco

Are you looking for a unique experience to enrich your holiday in Trentino? Why didn't you take advantage of the chance to discover local wines and distillates along the Wine and Flavour Route of the Region? Here is the list of the open wineries during the weekends on June. We are waiting for you…Cheers! th Wednesday | 2nd JUNE Saturday | 5th JUNE Sunday | 6 JUNE Ala – Azienda Agricola La Cadalora Ala – Azienda Agricola La Cadalora Ala – Azienda Agricola La Cadalora Cembra Lisignago – Cembra cantina di montagna Cembra Lisignago – Cembra cantina di montagna Cembra Lisignago – Cembra cantina di montagna Lavis – Azienda Agricola Maso Grener Giovo - Villa Corniole Mezzocorona - Azienda Agricola Donati Marco Mezzocorona - Azienda Agricola Donati Marco Isera - Cantina d'Isera Riva del Garda - Comai - Azienda Agricola Riva del Garda - Cantina Agraria Riva del Garda Lavis – Azienda Agricola Maso Grener San Michele all'Adige - Cantina Endrizzi Riva del Garda - Comai - Azienda Agricola Lavis - Cantina La Vis Trento - Mas dei Chini San Michele all'Adige - Cantina Endrizzi Mezzocorona - Azienda Agricola Donati Marco Trento - Mas dei Chini Mezzocorona – Dorigati Nogaredo – Distilleria Marzadro Nogaredo – Vivallis Nomi - Azienda Agricola Grigoletti Riva del Garda - Cantina Agraria Riva del Garda Riva del Garda - Comai - Azienda Agricola Rovereto – Letrari Soc. Agr. San Michele all'Adige - Cantina Endrizzi Trento - Mas dei Chini Saturday | 12 th JUNE Sunday | 13 th JUNE Nogaredo – Distilleria Marzadro Ala – Azienda Agricola La Cadalora Ala – Azienda Agricola La Cadalora Nogaredo – Vivallis Cembra Lisignago – Cembra cantina di montagna Cembra Lisignago – Cembra cantina di montagna Nomi - Azienda Agricola Grigoletti Giovo - Villa Corniole Mezzocorona - Azienda Agricola Donati Marco Riva del Garda - Cantina Agraria Riva del Garda Isera - Cantina d'Isera Riva del Garda - Comai - Azienda Agricola Riva del Garda - Comai - Azienda Agricola Lavis – Azienda Agricola Maso Grener Rovereto – Letrari Soc. -

I Ruderi Del Castello Di S.Gottardo a Mezzocorona.Valorizzare Un Luogo Storico E Naturalistico, Tra Didattica Ed Esplorazione

I ruderi del castello di S.Gottardo a Mezzocorona.Valorizzare un luogo storico e naturalistico, tra didattica ed esplorazione. Tesi di laurea a.a.2014-15 Università Studi di Trento Dip. Di Ingegneria Civile Ambientale Meccanica Corso laurea Magistrale in ingegneria Edile/Architettura Laureando David Paoli Relatori prof. A. Quendolo-prof. G. Cacciaguerra Per gentile concessione dell’autore con © dello stesso; riproduzione possibile citando come fonte l’autore e sito Indice Introduzione: presentazione del luogo 7 1. Inquadramento territoriale e paesaggistico 21 1.1 Geomorfologia 21 1.2 Centri abitati 23 1.2.1 Schema insediativo 26 1.3 Percorsi 26 2. Cenni storici 29 2.1 Preistoria 29 2.2 Periodo romano 30 2.3 Alto medioevo 30 2.4 Basso medioevo 31 2.4.1 Edificazione 31 2.4.2 Contesto storico 33 2.4.3 Il ruolo del castello 36 2.5 Castelli in grotta 41 2.6 Il santuario nel quattrocento 42 2.6.1 San Gottardo 42 2.6.2 Edificazione 43 2.6.3 Diffusione del culto e importanza 45 2.7 La leggenda 48 2.8 Il santuario-castello-eremo 51 2.8.1 “Restauri” del passato 52 2.9 Fonti storiche e tracce materiali 54 3. Il S. Gottardo: santuario-castello in grotta-eremo 69 3.1 Rilievo geometrico 69 3.2 Caratteri costruttivi e stratificazione 73 3.3 Analisi delle problematiche di conservazione 92 4. Identità di un luogo: il S. Gottardo 111 4.1 La questione del nome 111 4.2 Il S. Gottardo oggi - progetto culturale 113 4.3 Principi di progetto 117 5. -

Mercati E Fiere Settimanale Settimanale S

2018 2018 PLANNING PLANNING MAR APR MAG GIU LUG AGO SET OTT NOV DIC CLES - PINZOLO BRENTONICO 1 G 1 D PASQUA 1 M ZAMBANA 1 V 1 D CALCERANICA 1 M 1 S 1 L 1 G SANTI 1 S MOENA 2 V 2 L S. LORENZO BANALE 2 M CLES 2 S 2 L 2 G 2 D SEGONZANO 2 M 2 V STORO 2 D LAVIS 3 S 3 M 3 G 3 D 3 M 3 V 3 L 3 M 3 S 3 L S. LORENZO 4 D 4 M 4 V 4 L 4 M 4 S 4 M 4 G 4 D IN BANALE 4 M FOLGARIA 5 L 5 G 5 S 5 M 5 G 5 D 5 M 5 V (CARBONARE) 5 L 5 M C. di LEDRO TIARNO S. 6 M 6 V 6 D TRENTO 6 M 6 V 6 L 6 G 6 S PIEVE DI BONO 6 M 6 G 7 M 7 S 7 L 7 G 7 S 7 M 7 V 7 D LUSERNA 7 M 7 V C. di C. IVANO STRIGNO 8 G 8 D LAVIS (PRESSANO) 8 M 8 V 8 D 8 M 8 S FOLGARIA 8 L 8 G 8 S TRENTO BORGO VALSUGANA FOLGARIA - OSSANA TRENTO 9 V 9 L FIERA DI PRIMIERO 9 M 9 S 9 L 9 G 9 D PINZOLO 9 M 9 V 9 D 10 S 10 M 10 G 10 D LIVO 10 M 10 V 10 L REVÒ 10 M 10 S ALA 10 L STENICO 11 D S.