Weekly Articles 3/25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mailing Labels

Representative Henry J.C. Aquino Representative Della Au Belatti Representative Patrick Pihana Branco Hawaii State Capitol, Room 419 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 439 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 328 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Representative Ty J.K. Cullen Representative Linda Clark Representative Stacelynn K.M. Eli Hawaii State Capitol, Room 320 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 303 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 418 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street Honolulu, 415 S. Beretania Street Honolulu, HI 96813 HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Representative Sonny Ganaden Representative Cedric Asuega Representative Sharon E. Har Hawaii State Capitol, Room 330 Gates Hawaii State Capitol, Room 441 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 318 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Representative Mark J. Hashem Representative Troy N. Hashimoto Representative Daniel Holt Hawaii State Capitol, Room 424 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 332 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 406 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Representative Linda Ichiyama Representative Greggor Ilagan Representative Aaron Ling Johanson Hawaii State Capitol, Room 426 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 314 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 436 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street 415 S. Beretania Street Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Honolulu, HI 96813 Representative Jeanne Kapela Representative Bertrand Kobayashi Representative Dale T. Kobayashi Hawaii State Capitol, Room 310 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 403 Hawaii State Capitol, Room 326 415 S. -

2014 Political Corporate Contributions 2-19-2015.Xlsx

2014 POLITICAL CORPORATE CONTRIBUTIONS Last Name First Name Committee Name State Office District Party 2014 Total ($) Alabama 2014 PAC AL Republican 10,000 Free Enterprise PAC AL 10,000 Mainstream PAC AL 10,000 Collins Charles Charlie Collins Campaign Committee AR Representative AR084 Republican 750 Collins‐Smith Linda Linda Collins‐Smith Campaign Committee AR Senator AR019 Democratic 1,050 Davis Andy Andy Davis Campaign Committee AR Representative AR031 Republican 750 Dotson Jim Jim Dotson Campaign Committee AR Representative AR093 Republican 750 Griffin Tim Tim Griffin Campaign Committee AR Lt. Governor AR Republican 2,000 Rapert Jason Jason Rapert Campaign Committee AR Senator AR035 Republican 1,000 Rutledge Leslie Leslie Rutledge Campaign Committee AR Attorney General AR Republican 2,000 Sorvillo Jim Jim Sorvillo Campaign Committee AR Representative AR032 Republican 750 Williams Eddie Joe GoEddieJoePAC AR Senator AR029 Republican 5,000 Growing Arkansas AR Republican 5,000 Senate Victory PAC AZ Republican 2,500 Building Arizona's Future AZ Democratic 5,000 House Victory PAC AZ Republican 2,500 Allen Travis Re‐Elect Travis Allen for Assembly 2014 CA Representative CA072 Republican 1,500 Anderson Joel Tax Fighters for Joel Anderson, Senate 2014 CA Senator CA038 Republican 2,500 Berryhill Tom Tom Berryhill for Senate 2014 CA Senator CA008 Republican 2,500 Bigelow Frank Friends of Frank Bigelow for Assembly 2014 CA Representative CA005 Republican 2,500 Bonin Mike Mike Bonin for City Council 2013 Officeholder Account CA LA City Council -

September/October 2016 VOICE the ILWU Page 1

OF September/October 2016 VOICE THE ILWU page 1 HAWAII Volume 56 • No. 5 The VOICE of the ILWU—Published by Local 142, International Longshore & Warehouse Union September/October 2016 Please support candidates ADDRESS L A BE who support working people L The General Election is coming up on Tuesday, November 8. Don’t forget to vote! On the Inside A new ILWU Local in Hawaii ..... 2 Kauai pensioners enjoy their annual picnic ................. 3 Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell (second from left), U.S. Senator Mazie Hirono (fourth from right), and Oahu Business ILWU members on Oahu Agent Wilfred Chang (second from right) with ILWU members from Unit 4526 - Pacific Beach Hotel at the Labor Unity celebrate Labor Day Picnic held on Saturday, September 17, 2016 at the Waikiki Shell. Caldwell is an ILWU-endorsed candidate, and all and Labor Unity ..................4-5 Oahu members are urged to support him for Mayor in the upcoming General Election on November 8. Caldwell is endorsed by the ILWU because he has made working families on Oahu his priority. Improving public safety, repaving Kauai teams take state roads, fixing sewers, and housing homeless veterans are some of Caldwell’s accomplishments during his first term as golf tournament by storm ...... 6 Honolulu mayor. He has always listened to and tried to address the needs of ILWU members and their communities. Charter Amendments: What are these questions Trade Adjustment Assistance on the ballot? .......................... 7 approved for more HC&S workers Who are the candidates who work for working families? Special benefits and By Joanne Kealoha petitions for other sugar companies that Constitutional Amendment Social Sevices Coordinator closed, but each of those petitions were services under TAA recommendations ................ -

HCUL PAC Fund Financial Report for the Period Ending June 30, 2019

HCUL PAC Fund Financial Report For the Period Ending June 30, 2019 State PAC CULAC Total Beginning Balance 07/01/2018 58,614.22 1,210.53 59,824.75 ADD: PAC Contributions 15,649.90 9,667.00 25,316.90 Interest & Dividends 408.03 2.88 410.91 74,672.15 10,880.41 85,552.56 LESS: Contributions to state and county candidates (8,693.96) - (8,693.96) CULAC Contribution Transfer - (10,068.00) (10,068.00) Federal & State Income Taxes - - - Fees (Svc Chrgs, Chk Rrders, Rtn Chk, Stop Pmt, Tokens, Etc.) - (398.27) (398.27) Wire charges, fees & other - - - (8,693.96) (10,466.27) (19,160.23) Ending Balance as of 6/30/2019 65,978.19 414.14 66,392.33 Balance per GL 65,978.19 414.14 66,392.33 Variance - (0) - Contributions to State and County Candidates for Fiscal Year Ending June 2019 Date Contributed To Amount Total 7/25/2018 Friends of Mike Molina $ 100.00 Total for July 2018 $ 100.00 8/16/2018 David Ige for Governor 500.00 Total for August 2018 500.00 9/18/2018 Friends of Alan Arakawa 200.00 9/18/2018 Friends of Stacy Helm Crivello 200.00 Total for September 2018 400.00 10/2/2018 Friends of Mike Victorino 750.00 10/18/2018 Friends of Justin Woodson 150.00 10/18/2018 Friends of Gil Keith-Agaran 150.00 10/18/2018 Friends of Riki Hokama 200.00 Total for October 2018 1,250.00 11/30/2018 Plexcity 43.96 Total for November 2018 43.96 1/11/2019 Friends of Glenn Wakai 150.00 1/17/2019 Friends of Scott Nishimoto 150.00 1/17/2019 Friends of Sylvia Luke 150.00 1/17/2019 Friends of Gil Keith-Agaran 300.00 1/17/2019 Friends of Della Au Belatti 150.00 1/17/2019 Friends -

Hawaii Clean Energy Final PEIS

1 APPENDIX A 2 3 Public Notices Notices about the Draft Programmatic EIS Appendix A The following Notice of Availability appeared in the Federal Register on April 18, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-1 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-2 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawaii placed the following advertisement in The Garden Island on May 5 and 9, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-3 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawaii placed the following advertisement in the West Hawaii Today on May 6 and 12, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-4 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawaii placed the following advertisement in the Hawaii Tribune Herald on May 7 and 12, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-5 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawaii placed the following advertisement in the Maui News on May 8, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-6 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawaii placed the following advertisement in the Maui News on May 13, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-7 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawaii placed the following advertisement in the Maui News on May 18, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-8 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawaii placed the following advertisement in the Molokai Dispatch on May 7 and 14, 2014. Hawai‘i Clean Energy Final PEIS A-9 September 2015 DOE/EIS-0459 Appendix A DOE-Hawai‘i placed the following advertisement in the Star-Advertiser on May 14 and 19, 2014. -

July 2018 Engineers News

OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCAL 3 WWW.OE3.ORG Vol. 76 #7/JULY 2018 fifty-year members honored Retirees Enjoy the Good Life at Dixon Picnic Election Notice See page 27 for important information regarding the 2018 election of Officers and Executive Board Members. ON THE COVER Congratulations to all of our 50-year honorees, including 16 those able to attend last month’s Retiree Picnic, featured here. The other photos featured are from projects throughout the year these honorees joined, 1968. See coverage of the Retiree Picnic here, and visit our online gallery at www.oe3.org. (A complete list of 50-year honorees is available on pages 14-15.) 18 ALSO INSIDE Public Employee News Janus 08 information The Supreme Court’s decision about Janus may not have 08 gone the way we wanted, but Local 3’s Public Employee 26 Department is proactively handling the situation. Read about it here and get the details on some of our standout Public Employee members and contracts. 10 28th Annual Surveyors Competition This year’s competition had the biggest turnout ever and 10 some of the best talent the Northern California Surveyors Joint Apprenticeship Committee (NCSJAC) has ever seen. See some of the winners and read about how these apprentices got their start in one of Local 3’s most lucrative and growing professions. Local 3 Hawaii Primary Election Recommendations Hawaii’s Primary Election is Aug. 11. Be prepared by 10 12 checking out Local 3’s recommendations for this election here and online. Then use these recommendations, when you cast your vote! OE3 JATC Top Hand Competition: Sept. -

Financial Audit of GMO Money Blocking a GMO Labeling Bill

Financial Audit of GMO Money blocking a GMO Labeling Bill Politicians allow experimental GMO field trials near our homes, schools & oceans Our Politicians have turned our ‘Aina into a Chemical Wasteland The final deadline to hear a GMO labeling bill is gone, and the Chairpersons of both Senate and House Agriculture, Health, and Economic Development/Consumer Protection Committees refuse to hold a hearing. In November we will vote these corrupt Committee Chairpersons out that blocked a GMO labeling bill this year: Senate: Clarence Nishihara, Rosalyn Baker House: Clift Tsuji, Calvin Say, Ryan Yamane, Bob Herkes GMO Money to State Legislators 2008 2009 2011 Neil Abercrombie 1,000 1,500 Rosalyn Baker 750 500 500 (1,500) Kirk Caldwell 550 (Fred Perlak 500) Jerry Chang 500 500 Isaac Choy 500 Suzanne Chun Oakland 1000 Ty Cullen 250 Donovan Dela Cruz 500 (Dow 500) Will Espero 500 500 Brickwood Galuteria 500 Colleen Hanabusa 500 Mufi Hannemann (Dean Okimoto) 250 1,000 Sharon Har 1,000 1,000 500 Clayton Hee 1,000 500 (2,000) (Dow 500) (Syngenta 1000) Bob Herkes 750 500 500 Ken Ito 500 500 500 Gil Kahele 500 Daryl Kaneshiro 200 Michelle Kidani 250 500 (Dow 500) (DuPont 500) (Perlak 500) Donna Mercado Kim 1,000 Russell Kokubun 500 Ronald Kouchi 500 Sylvia Luke 250 (Perlak 500) Joe Manahan 500 500 Ernie Martin (Alicia Maluafiti) 250 (Perlak 500) Barbara Marumoto (Bayer 500) Angus McKelvey 500 Clarence Nishihara 750 500 Scott Nishimoto (Syngenta 250) GMO MONEY 2008 2009 2011 Blake Oshiro (Fred Perlak) 500 Calvin Say 2010 Biotech Legislator 1,000 500 -

Lāhui Ha W Ai'i

KOHO PONO RC 2017.indd 1 2017.indd RC PONO KOHO 7/20/17 8:22 PM 8:22 7/20/17 HAWAIIAN HOME LANDS | SUPPORT HB451 • PASSED Reduces the minimum Hawaiian blood quantum requirement of certain successors to lessees of Hawaiian Home Lands from 1/4 to 1/32 to ensure that lands remain in Kanaka Maoli families for generations to come. With over 20,000 applicants on the list waiting to receive land awards, the lowering of blood quantum should only be used for successors who are related to Hawaiian Home Lands lessees. The State Legislature should work to ensure that the needs of native Hawaiian beneficiaries are addressed in a timely manner by properly funding DHHL. OHA TRUSTEE SELECTION | OPPOSE SCR85 • FAILED Requests OHA convene a task force of Hawaiian leaders, legal scholars, and a broad representation of members of the Hawaiian community to review and consider whether its fiduciary duty to better the conditions of Hawaiians and manage its resources to meet the needs of Hawaiian beneficiaries would be better served by having trustees appointed rather KOHO PONO means to Elect or Choose Wisely. than elected. This resolution urges the further disenfranchisement of the Kanaka Maoli This Legislative Report Card will help you make an people by taking away their right to vote for OHA Trustees who control a $600 million dollar informed decision when choosing a candidate to public trust and 28,219 acres of valuable Hawai`i lands that include sacred and conservation represent your voice in government. KOHO PONO sites on behalf of Kanaka Maoli. -

Policy Diffusion Assistance in the Amelioration of Homelessness on the Island of O`Ahu, Hawai`I

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2019 Policy Diffusion Assistance in the Amelioration of Homelessness on the Island of O`ahu, Hawai`i Anita Tanner Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Anita Miller Tanner has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Paul Rutledge, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Eliesh Lane, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Joshua Ozymy, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty The Office of the Provost Walden University 2019 Abstract Policy Diffusion Assistance in the Amelioration of Homelessness on the Island of O`ahu, Hawai`i by Anita Miller Tanner MPA, Troy University, 2001 BS, San Diego State University, 1994 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University November 2019 Abstract The issue of homelessness is one that many cities and states in the United States have to contend with; however, the issue of homelessness on an island can be even more difficult to find viable solutions. -

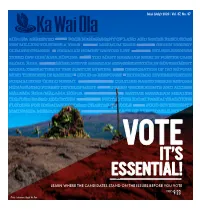

Learn Where the Candidates Stand on the Issues Before

Iulai (July) 2020 | Vol. 37, No. 07 VOTE IT’S ESSENTIAL! LEARN WHERE THE CANDIDATES STAND ON THE ISSUES BEFORE YOU VOTE PAGES 9-23 Photo: Lehuanani Waipä Ah Nee MARK YOUR CALENDARS! DID YOU FINAL DAY TO REGISTER TO RECEIVE BALLOT BY MAIL KNOW... go to olvr.hawaii.gov to register online ▸ 16-year-olds can CHECK YOUR MAIL! pre-register to vote? Delivery of ballot packages begin ▸ If you will be 18 by PLACE YOUR BALLOT IN election day, that you THE MAIL BY THIS DATE! can vote? Ballots must be received by August 8 at 7:00 pm ▸ You can register to vote on your phone? ▸ Hawai‘i has mail-in elections this year? HOW TO VOTE BY MAIL YOUR MAIL BALLOT WILL INCLUDE: GO TO olvr.hawaii.gov TO REGISTER TO VOTE 1. BALLOT 2. SECRET BALLOT 3. RETURN Before voting your ballot, review ENVELOPE ENVELOPE instructions and the contests and After voting your ballot, re-fold it and Read the affirmation statement and candidates on both sides of the seal it in the secret ballot envelope. sign the return envelope before ballot. To vote, completely darken in The secret ballot envelope ensures returning it to the Clerk’s Office. Upon the box to the left of the candidate your right to secrecy as the ballots are receipt of your return envelope, the using a black or blue pen. opened and prepared for counting. Once Clerk’s Office validates the signature sealed, place the secret ballot envelope on the envelope. After your signature is in the return envelope. -

Hawaii House Blog: the Ledge: GMO Taro Pagina 1 Van 6

Hawaii House Blog: The Ledge: GMO Taro pagina 1 van 6 BLOG ZOEKEN BLOG MARKEREN Volgende blog»Blog maken | Aanmelden Hawaii House Blog News and commentary from the Majority of the Hawaii House of Representatives Followers (19) Monday, February 2, 2009 Search Hawaii The Ledge: GMO Taro House Blog Follow this blog Search Here Go House Blog Links 2009 House Directory 19 Followers Capitol Food View All Drive Calendar Blogging from Community the state Newsletters capitol... Media Room Photo Gallery In this episode of "The Ledge" you will hear a plea to lawmakers from a kanaka maoli to Reps in the protect the Hawaiian taro. News The issue of genetically modified taro comes up again this legislative session. Three bills that you Label Cloud should keep an eye on include: 25th Legislature 9/11 Accolades Aerospace Industry Contact Us HB1663, which proposes to prohibit any kind of Aerospace Industry; testing, development, importation or planting of Rep. Kyle Yamashita Georgette Agriculture Aha genetically modified taro in Hawaii. This bill was Moku Council; Rep. Mele Deemer introduced by the Hawaiian Legislative Caucus, Carroll Akaka Bill Alcoholism Aloha 808-586-6133 chaired by Rep. Mele Carroll. deemer@capitol. Airlines Aloha Stadium arson Art hawaii.gov SB709, which places a moratorium on in Public Places Twitter ID: Baby Safe Haven genetically modifying any Hawaiian taro in Barack Obama Bert A. georgettedeemer Hawaii and testing, planting, or growing any Kobayashi Big Hawaiian taro within the State that has been Island Big Island 2008 blogs Brian Thelma Dreyer genetically modified outside the State. This bill Kajiyama Budget 808-587-7242 was introduced by Senator Kalani English. -

2020 AFL-CIO General Endorsements

Vote 2 0 2 0 G E N E R A L E L E C T I O N E N D O R S E M E N T S H A W A I ‘ I S T A T E A F L - C I O Unions of Hawai‘i U.S. PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN (D) U.S. CONGRESS DIST. 2 KAIALI‘I KAHELE (D) STATE SENATE–OAHU DIST. 9 STANLEY CHANG (D) DIST. 10 LES IHARA (D) DIST. 19 KURT FEVELLA (R) DIST. 22 DONOVAN DELA CRUZ (D) DIST. 25 CHRIS LEE (D) STATE HOUSE–OAHU DIST. 18 MARK HASHEM (D) DIST. 39 TY CULLEN (D) DIST. 19 BERTRAND KOBAYASHI (D) DIST. 40 ROSE MARTINEZ (D) DIST. 20 JACKSON SAYAMA (D) DIST. 41 DAVID ALCOS (R) DIST. 22 ADRIAN TAM (D) DIST. 43 STACELYNN ELI (D) DIST. 24 DELLA BELATTI (D) DIST. 44 CEDRIC GATES (D) DIST. 30 SONNY GANADEN (D) DIST. 47 SEAN QUINLAN DIST. 34 GREGG TAKAYAMA (D) DIST. 49 SCOT MATAYOSHI (D) DIST. 35 ROY TAKUMI (D) DIST. 50 PATRICK BRANCO (D) DIST. 36 TRISH LA CHICA (D) DIST. 51 LISA MARTEN (D) DIST. 37 RYAN YAMANE (D) COUNTY–OAHU HONOLULU MAYOR KEITH AMEMIYA HONOLULU PROSECUTING ATTORNEY STEVE ALM DIST. 3 ESTHER KIA'AINA OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS TRUSTEE AT-LARGE KEONI SOUZA U.S. PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN (D) U.S. CONGRESS DIST. 2 KAIALI‘I KAHELE (D) STATE SENATE–HAWAII, MAUI, KAUAI DIST. 2 JOY SAN BUENAVENTURA (D) DIST. 5 GIL KEITH-AGARAN (D) STATE HOUSE–HAWAII, MAUI, KAUAI DIST. 1 MARK NAKASHIMA (D) DIST.