The House That Ghosts Built (And Mediums Performed)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

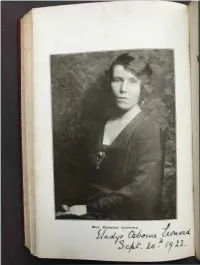

British College of Psychic Science

Quarterly Transactions of the British College of Psychic Science. Vol. I.—No. 4. January, 1923. EDITORIAL NOTES. With the present issue, Psychic Science completes its first year, and the thanks of its sponsors are cordially extended to all those whose sympathetic support has carried the under taking so successfully through a difficult period. * * * * * The aim and scope of our “ Quarterly” is now, wetrust, sufficiently well defined. The aim is essentially a constructive one, whilst analytic in the quest of truth ; its scope catholic, disdaining no form of enquiry and investigation which may bear upon the many obscure problems of spiritual interaction with Matter and physical life, through all the tenebrous avenues of the psychic regions as yet untraversed by Mind. * * * * * We shall endeavour, in the year to come, to give further and clearer effect to these purposes and thereby to assist the College towards a more definite realization of its destined sphere of usefulness ; that it may bring to birth in vigorous form the embryonic idea now forming in the public mind of the University of Psychic Science that is to be. It is at least legitimate to hope that the College may be the incubator of such an idea, and a foster-mother until it be fully fledged. The pages of Psychic Science will be open to correspondence and suggestions towards this end. 304 Quarterly Transactions B.C.P.S. For this must surely come to pass, and in that day we look to see the ministers of religion and the professors of science working together with united aim, the “ tabu ” of religious bigotry, on the one hand, and of intellectual arrogance on the other, being laid aside, and a fraternal understanding established for the great work of re-edification now to be done in the rearing of a new Temple of Humanity, in which truth shall be worshipped and intolerance and super stition shall have no place. -

Ghostly Molds How to Make a Plaster Cast of Your Hand, Even If You Are Not a Spirit

SI M-A 2009 pgs 1/27/09 11:40 AM Page 22 NOTES ON A STRANGE WORLD MASSIMO POLIDORO Ghostly Molds How to make a plaster cast of your hand, even if you are not a spirit ince the early days of Spiritualism, public became aware of their existence porters of this method agree that it is when mediums began producing thanks also to articles in popular maga- possible to reproduce hands of different S physical phenomena, paraffin-wax zines such as Scientific American. sizes and shapes and that the glove molds supposedly modeled around mate- Some of the plaster casts of these might be easily hidden on the medium’s rialized “spirit hands” during séances were molds are still preserved at the Institut body. To obtain such a glove showing considered some of the best pieces of evi- Mètapsychique International in Paris the hand’s fingerprints and its distinc- dence of the paranormal. (www.metapsychique.org), a fact that in tive lines, one should first impress a real Some of these molds, in fact, seem- part explains why the interest in the hand on dental wax, which allows a ed to possess the characteristics of phenomena periodically resurfaces. much sharper outline of the skin’s tex- “permanent paranormal objects.” The ture than plaster. This imprinting will at Alternatives to the Paranormal empty paraffin molds found at the con- once be used as a mold for making a clusion of séances, it was thought, Many (e.g., Coleman 1994a; 1995a) rubber glove showing all the typical could still be intact only because the have pointed out various possible nat- marks of a real hand. -

The Vital Message

The Vital Message By Arthur Conan Doyle Classic Literature Collection World Public Library.org Title: The Vital Message Author: Arthur Conan Doyle Language: English Subject: Fiction, Literature, Children's literature Publisher: World Public Library Association Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net World Public Library The World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net is an effort to preserve and disseminate classic works of literature, serials, bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other reference works in a number of languages and countries around the world. Our mission is to serve the public, aid students and educators by providing public access to the world's most complete collection of electronic books on-line as well as offer a variety of services and resources that support and strengthen the instructional programs of education, elementary through post baccalaureate studies. This file was produced as part of the "eBook Campaign" to promote literacy, accessibility, and enhanced reading. Authors, publishers, libraries and technologists unite to expand reading with eBooks. Support online literacy by becoming a member of the World Public Library, http://www.WorldLibrary.net/Join.htm. Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net www.worldlibrary.net *This eBook has certain copyright implications you should read.* This book is copyrighted by the World Public Library. With permission copies may be distributed so long as such copies (1) are for your or others personal use only, and (2) are not distributed or used commercially. Prohibited distribution includes any service that offers this file for download or commercial distribution in any form, (See complete disclaimer http://WorldLibrary.net/Copyrights.html). -

El Esceptico

escescel éépticoptico la revista para el fomento de la razón y la ciencia publicación trimestral nº 10 otoño-invierno 2000 El fin del hambre en el mundo Plausibilidad, trascendencia y la epidemia panspérmica Los caballeros de ninguna parte Entrevista a John Allen Paulos número extra Edita ARP - Sociedad para el Avance del Pensamiento Crítico PVP: 5,4 euros / 900 ptas. escel éptico la revista para el fomento de la razón y la ciencia ARP - Sociedad para el Avance del Pensamiento Crítico DIRECCIÓN Julio Arrieta PRESIDENTE Alfonso López Borgoñoz (coordinador) Félix Ares de Blas Víctor R. Ruiz VICEPRESIDENTE CONSEJO DE REDACCIÓN José Mª Bello Diéguez Félix Ares de Blas SECRETARIO Javier E. Armentia Ferran Tarrasa Blanes José Mª Bello Diéguez José Luis Calvo Buey TESORERO Luis Alfonso Gámez Alfonso López Borgoñoz Pedro Luis Gómez Barrondo DIRECTOR EJECUTIVO Borja Marcos Pedro Luis Gómez Barrondo SECCIONES VOCALES Primer Contacto,Pedro Luis Gómez Barrondo Luis Alfonso Gámez Mundo Escéptico, Sergio López Borgoñoz Borja Marcos Cuaderno de Bitácora,Javier Armentia Teresa González de la Fe Guía Digital, Ernesto Carmena Paranormalia, Julio Arrieta y Borja Marcos CONSEJO ASESOR De Oca a Oca, Félix Ares de Blas Alfonso Afonso Un marciano en mi buzón, Luis González Manso José María Alcaide Crónicas desde Magonia, Luis Alfonso Gámez Carlos Álvarez Sillón Escéptico, José Luis Calvo Buey Javier Armentia Julio Arrieta DELEGADO DE EDICIÓN Y DISTRIBUCIÓN José Luis Calvo Buey Alfonso López Borgoñoz Luis Capote COMPAGINACIÓN Y PRODUCCIÓN Ernesto Carmena Mercedes -

The Witch of Lime Street: Seacute;Ance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World Online

q6gpo (Ebook pdf) The Witch of Lime Street: Seacute;ance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World Online [q6gpo.ebook] The Witch of Lime Street: Seacute;ance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World Pdf Free David Jaher *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #362942 in Books Jaher David 2016-10-11 2016-10-11Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .90 x 5.20l, .0 #File Name: 0307451070448 pagesThe Witch of Lime Street Seance Seduction and Houdini in the Spirit World | File size: 62.Mb David Jaher : The Witch of Lime Street: Seacute;ance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Witch of Lime Street: Seacute;ance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. scientists vs. spiritualists in the 1920sBy lisaleo (Lisa Yount)This nonfiction book describes the investigation of scientists from Scientific American magazine and several eastern universitiesmdash;not to mention famous magician and anti-spiritualist crusader Harry Houdinimdash;of probably the most famous medium of the early to mid-1920s, a woman generally known as Margery. Margery, whose real name was Mina Crandon, supposedly channeled her older brother, Walter, who had been killed in a train accident. She and Walter specialized in physical manifestationsmdash;moving furniture, ringing bells, and the like, along with production of filmy ectoplasmmdash;rather than messages from sittersrsquo; deceased loved ones, as some other mediums did.Margery was different from most other mediums of the era in other ways, too. -

INDICE -.:: Biblioteca Virtual Espírita

INDICE A CIÊNCIA DO FUTURO......................................................................................................................................... 4 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPIRITISMO................................................................................................................................ 5 A PALAVRA DOS CIENTISTAS ..................................................................................................................... 6 UMA NOVA CIÊNCIA...................................................................................................................................... 7 O ESPIRITISMO ............................................................................................................................................. 8 O ESPIRITISMO E A METAPSÍQUICA........................................................................................................... 8 O ESPIRITISMO E PARAPSICOLOGIA ......................................................................................................... 9 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPÍRITO .................................................................................................................................... 10 A CIÊNCIA ESPÍRITA OU DO ESPÍRITO ............................................................................................................. 13 1. ALLAN KARDEC E A DEFINIÇÃO DO ESPIRITISMO, SOB O ASPECTO CIENTÍFICO......................... 14 2. A CIÊNCIA E SEUS MÉTODOS. ............................................................................................................. -

CFI-Annual-Report-2018.Pdf

Message from the President and CEO Last year was another banner year for the Center the interests of people who embrace reason, for Inquiry. We worked our secular magic in a science, and humanism—the principles of the vast variety of ways: from saving lives of secular Enlightenment. activists around the world who are threatened It is no secret that these powerful ideas like with violence and persecution to taking the no others have advanced humankind by nation’s largest drugstore chain, CVS, to court unlocking human potential, promoting goodness, for marketing homeopathic snake oil as if it’s real and exposing the true nature of reality. If you medicine. are looking for humanity’s true salvation, CFI stands up for reason and science in a way no look no further. other organization in the country does, because This past year we sought to export those ideas to we promote secular and humanist values as well places where they have yet to penetrate. as scientific skepticism and critical thinking. The Translations Project has taken the influential But you likely already know that if you are reading evolutionary biology and atheism books of this report, as it is designed with our supporters in Richard Dawkins and translated them into four mind. We want you not only to be informed about languages dominant in the Muslim world: Arabic, where your investment is going; we want you to Urdu, Indonesian, and Farsi. They are available for take pride in what we have achieved together. free download on a special website. It is just one When I meet people who are not familiar with CFI, of many such projects aimed at educating people they often ask what it is we do. -

Ghost Hunting

Haunted house in Toledo Ghost Hunting GHOST HUNTING 101 GHOST HUNTING 102 This course is designed to give you a deeper insight into the This course is an extended version of Ghost Hunting 101. While world of paranormal investigation. Essential characteristics of it is advised that Ghost hunting 101 be taken as a prerequisite, it a paranormal investigation require is not necessary. This class will expand on topics of paranormal a cautious approach backed up investigations covered in the first class. It will also cover a variety with scientific methodology. Learn of topics of interest to more experienced investigators, as well as, best practices for ghost hunting, exploring actual techniques for using equipment in ghost hunting, investigating, reviewing evidence and types of hauntings, case scenarios, identifying the more obscure presenting evidence to your client. Learn spirits and how to deal with them along with advanced self- from veteran paranormal investigator protection. Learn from veteran paranormal investigator, Harold Harold St. John, founder of Toledo Ohio St. John, founder of the Toledo Ohio Ghost Hunters Society. If you Ghost Hunters Society. We will study have taken Ghost Hunting 101 and have had an investigation, you the different types of haunting's, a might want to bring your documented evidence such as pictures, typical case study of a "Haunting", the EVP’s or video to share with your classmates. There will be three Harold St. John essential investigating equipment, the classes of lecture and discussions with the last session being a investigation process and how to deal field trip to hone the skills you have learned. -

Tall Tales About Mind and Brain

Tall Tales about Mind and Brain Supporting Resource Pack for Teachers Contents The Royal Society of Edinburgh ..................................................................................................1 Introduction..................................................................................................................................2 Supporting Resources for Teachers.............................................................................................4 Memory and Learning...............................................................................................................4 - Memory a User’s Guide. Professor Alan Baddeley CBE FRS,Professor of Psychology, University of York - The Myth of the Incredible Witness. Professor Tim Valentine, Professor of Psychology, Goldsmiths, University of London - The Perils of Intuition. Professor David G Myers, Professor of Psychology, Hope College, Holland - Magic and the Paranormal: The Psychology. Dr Peter Lamont, School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, the University of Edinburgh Intelligence ................................................................................................................................8 - Bigger and Better? Brain Size and Species. Dr David Carey, School of Psychology, University of Aberdeen - Intelligence. Professor Michael Anderson, Department of Psychology, the University of Western Australia, Perth - Myths about Intelligence and Old Age. Professor Ian J Deary FBA FRSE, Professor of Differential Psychology, Department -

Texas Paranormalists

! TEXAS PARANORMALISTS David!Goodman,!B.F.A,!M.A.! ! ! Thesis!Prepared!for!the!Degree!of! MASTER!OF!FINE!ARTS! ! ! UNIVERSITY!OF!NORTH!TEXAS! December!2015! ! APPROVED:!! Tania!Khalaf,!Major!Professor!!!!! ! Eugene!Martin,!Committee!Member!&!!!! ! Chair!for!the!Department!of!Media!Arts ! Marina!Levina,!Committee!Member!!!! ! Goodman, David. “Texas Paranormalists.” Master of Fine Arts (Documentary Production and Studies), December 2015, 52 pp., references, 12 titles. Texas Pararnormalists mixes participatory and observational styles in an effort to portray a small community of paranormal practitioners who live and work in and around North Texas. These practitioners include psychics, ghost investigators, and other enthusiasts and seekers of the spirit world. Through the documentation of their combined perspectives, Texas Paranormalists renders a portrait of a community of outsiders with a shared belief system and an unshakeable passion for reaching out into the unknown. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright!2015! By! David!Goodman! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ii! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Page! PROSPECTUS………………………………………………………………………………………………………!1! Introduction!and!Description……………………………………………………………………..1! ! Purpose…………………………………………………………………………………………….………3! ! Intended!Audience…………………………………………………………………………………….4! ! Preproduction!Research…….....................…………………………………………...…………..6! ! ! Feasibility……...……………...…………….………………………………………………6! ! ! Research!Summary…….…...…..……….………………………………………………7! Books………...………………………………………………………………………………..8! -

Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality from Silent Cinema to the Digital Era

Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality from Silent Cinema to the Digital Era. Edited by Murray Leeder. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015 (307 pages). Anton Karl Kozlovic Murray Leeder’s exciting new book sits comfortably alongside The Haunted Screen: Ghosts in Literature & Film (Kovacs), Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife (Ruffles), Dark Places: The Haunted House in Film (Curtis), Popular Ghosts: The Haunted Spaces of Everyday Culture (Blanco and Peeren), The Spectralities Reader: Ghost and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory (Blanco and Peeren), The Ghostly and the Ghosted in Literature and Film: Spectral Identities (Kröger and Anderson), and The Spectral Metaphor: Living Ghosts and the Agency of Invisibility (Peeren) amongst others. Within his Introduction Leeder claims that “[g]hosts have been with cinema since its first days” (4), that “cinematic double exposures, [were] the first conventional strategy for displaying ghosts on screen” (5), and that “[c]inema does not need to depict ghosts to be ghostly and haunted” (3). However, despite the above-listed texts and his own reference list (9–10), Leeder somewhat surprisingly goes on to claim that “this volume marks the first collection of essays specifically about cinematic ghosts” (9), and that the “principal focus here is on films featuring ‘non-figurative ghosts’—that is, ghosts supposed, at least diegetically, to be ‘real’— in contrast to ‘figurative ghosts’” (10). In what follows, his collection of fifteen essays is divided across three main parts chronologically examining the phenomenon. Part One of the book is devoted to the ghosts of precinema and silent cinema. In Chapter One, “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theater, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny”, Tom Gunning links “Freud’s uncanny, the hope to use modern technology to overcoming [sic] death or contact the afterlife, and the technologies and practices that led to cinema” (10). -

Spiritualism and Social Conflict in Late Imperial Russia

Mysterious knocks, flying potatoes and rebellious servants: Spiritualism and social conflict in late Imperial Russia Julia Mannherz1 (Oriel College Oxford) Strange things occurred in the night of 13 December, 1884, in the city of Kazan on the river Volga. As Volzhskii vestnik (The Volga Herald) reported, unidentifiable raps were heard in the flat rented by the retired officer Florentsov on Srednaia Iamskaia Street. Before the newspaper described what had actually been observed, it made it clear that ‘all descriptions here are true facts, as has been ascertained by a member of our newspaper’s editorial board’. This assertion was deemed necessary because the phenomena were of a kind ‘regarded as “inexplicable”‘. On the evening of 13 December: Mr. Florentsov was just about to go to bed, when a loud rap on his apartment’s ceiling was heard, which caused worry even to the neighbours. At about the same time, potatoes and bricks began to fly out of the oven pipe and smashed the kitchen window. On the 14th the ‘phenomena’ continued all day long and were accompanied by many comical episodes. About 10 well-known officers came to Mr. Florentsov’s apartment. They put a heavy pole against the oven-door, but the shaft was not strong enough and it soon flew to one side. [After this] potatoes rolled out beneath the furniture, fell from the walls, rained down from the ceiling; sometimes a brick appeared at the scene of action. One officer was hit by a potato on his head, another one on his nose, some were hit by the bullets of this invisible foe at their backs, shoulders and so on.