The Experiment of American Pedestrian Malls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

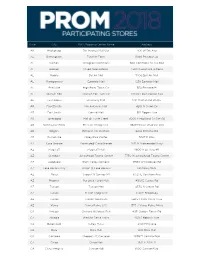

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

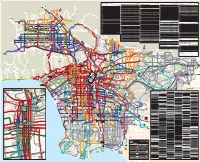

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

UEZ Newsletter

CITY OF PATERSON Volume II Issue II Fall 2008 PRESORT STANDARD MAIL Urban Enterprise Zone US POSTAGE PAID Message from the UEZ Director PATERSON, NJ PERMIT #542 am happy to report that the Paterson UEZ has welcomed approximately 39 I new business members into the Urban Enterprise Zone family since April our last Newsletter. As of October 1, 2008 the UEZ is reporting to the Department of Consumer Aff airs What’s Inside (DCA) in Trenton. The Economic Development Authority (EDA) Chairs the UEZ Message from the UEZ Authority meetings (Trenton) for project proposals; so it now appears we have the best of both worlds. Page 1 In the last Newsletter, my message stated that legislation has changed to allow Message from Mayor Torres businesses with gross sales up to 3 million dollars to claim tax exemption at the point Page 3 of sale for allowable items. It recently has been reported that legislation once again is on the Senate fl oor that may increase the 3 million dollars to 7 million dollars. We About the Program are still holding out hope that the program may return back to its original format whereby all UEZ member businesses can take the exemption at the point of sale. For Page 4 now, the ceiling remains at 3 million however; all member businesses are entitled to the tax exemption benefi t whether it is taken by rebate or at the point of sale. If UEZ Business Spotlight you need additional information on the criteria for the tax exemption, please call the UEZ offi ces. -

The CCIS Experiment : Comparing Transit Information Retrieval Modes

. HE UMTA-MA-06-01 26-84-4 I 8.5 DOT-TSC-UMTA-84-1 .A3 7 no DOT- T SC- The CCIS Experiment: lf MT A- 84-1 J.S. Department Comparing Transit of Transportation Urban Mass Information Retrieval Modes Transportation Administration at the Southern California Rapid Transit District Robert 0. Phillips Wilson Hill Associates, Inc. 140 Federal Street Boston M A 021 10 March 1984 Final Report This document is available to the public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161. UMTA Technical Assistance Program NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse prod- ucts or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers 1 names appear herein solely because they are con- sidered essential to the object of this report. f&f' 'ho Technical Report Documentation Page I • Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UMTA-MA- 06-0126-84-4 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date ^THE CCIS EXPERIMENT: COMPARING TRANSIT March 1984 INFORMATION RETRIEVAL MODES AT TH 6. Performing Organization Code CALIFORNIA RAPID TRANSIT DIST DTS-64 8. Performing Organization Report No. 7. Authors) DOT-TSC-UMTA-8 4-1 Robert O. Phillips 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Wilson Hill Associates, Inc.* UM464/R4653 140 Federal Street 11. Contract or Grant No. Boston, MA 02110 DTRS-57-81-00054 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. -

Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo

Reports Upjohn Research home page 1-1-2018 Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo Jim Robey W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, [email protected] Randall W. Eberts W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, [email protected] Lee Adams W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research Kathleen Bolter W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research Don Edgerly W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://research.upjohn.org/reports Citation Robey, Jim, Randall W. Eberts, Lee Adams, Kathleen Bolter, Don Edgerly, Marie Holler, Brian Pittelko, Claudette Robey. 2018. "Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo." Prepared for the City of Kalamazoo and the Brownfield Redevelopment Authority. https://research.upjohn.org/reports/231 This title is brought to you by the Upjohn Institute. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Jim Robey, Randall W. Eberts, Lee Adams, Kathleen Bolter, Don Edgerly, Marie Holler, Brian Pittelko, and Claudette Robey This report is available at Upjohn Research: https://research.upjohn.org/reports/231 Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo Prepared for the City of Kalamazoo and the Brownfield Redevelopment Authority Initial draft: June 14, 2017 Final document issued: March 20, 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Overview of Recommendations 7 Recommendations for Downtown Growth 14 Priority Objective: Business Recruitment and Retention -

Girl Scout Seniors & Ambassadors Gold Award Take Action Project Roundtable

Every Girl Scout is a G.I.R.L. (Go-getter, Innovator, Risk-taker and Leader) and there is power in every G.I.R.L. Girl Scouts of Northern New Jersey has a variety of fun and challenging activities, events, and trips that will help girls unleash their power. Check out the following pages for your Girl Scout program level and let your girls decide where their interests and talents lie. Do the girls want to stay fit? Do they want to try some STEM activities? Those opportunities and more are available through the LINK. They might event want to work on Girl Scouting’s highest awards. From STEM to sports, arts to travel, there are many new opportunities for every girl to find her spark. Artists, inventors and designers alike will love the chance to join the Maker Weekend at Jockey Hollow Camp. Girl Scout Brownies will get a chance to program an adorable Bee Bot Robot, in “Brownie Bots.” Girl Scout Brownies and Juniors will get hands-on experience with STEAM concepts, like engineering and design, as they participate in Girls’ Fast Track Races, Powered by Ford. Girl Scout Cadettes, Seniors and Ambassadors will experience the beautiful city of Savannah, Georgia as they travel to the Birthplace of Girl Scouting. Whatever they try, your girls will have fun, while engaging in girl-led, collaborative and hands-on experiences. Girl Scouts of Northern New Jersey offers the LINK Patch Program. Attend LINK Program Activities in the following categories and earn the LINK Lock & Chain Patch Set: Civics & History; Highest Awards; Excursions; STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math); Life Skills; Fine Arts; Healthy Living; and College & Careers. -

ESRI's Guide to Redlands

ESRI’s Guide to Redlands A Unique and Livable Community Join a World-Leading Software Company ESRI has more to offer than just a great career. ESRI is best known for its cutting edge geographic information system (GIS) technology, but it’s also a great place to work. Our employees—technical and nontechnical alike— find that ESRI offers a challenging work environment that promotes autonomy and fosters leadership. We Subscribe to the ESRI Careers Blog to offer an outstanding benefits package. The workplace is stay up to date on hot jobs, recruiting friendly and welcoming; it is a place where employees events, and other career-related news. collaborate with coworkers in a team-oriented, creative Visit www.esri.com/careersblog. environment. Ideally located in Southern California, Redlands is a town known for embracing family, culture, history, and recreation. We are seeking talented professionals in all areas to come grow with us. Discover who we are and why we’re so excited about what we do at www.esri.com/careers. Copyright © 2008 ESRI. All rights reserved. The ESRI globe logo, ESRI, and www.esri.com are trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of ESRI in the United States, the European Community, or certain other jurisdictions. ESRI is an Equal Opportunity Emplyer. Inside the Guide 2 WELCOME TO REDLANDS 2 ESRI’s Guide to Redlands 3 A Rich Heritage 5 Historic Redlands 6 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION Photo courtesy of A.K. Smiley Public Library 6 Tourist and New Resident Information 9 Getting Around 10 Getting to Redlands 11 Map of Redlands 12 RESTAURANT GUIDE 12 Where to Eat 15 PLACES TO GO, THINGS TO DO 15 Redlands for Free 16 Parks and Open Spaces 17 Exercise and Recreation 18 Performing Arts 19 Shopping 19 Museums 1 20 DAY TRIPS 20 Visit with Nature in the Local Mountains 20 Areas of Interest Produced by ESRI, Redlands, California Copyright © 2008 ESRI. -

COUNTY of PASSAIC New Jersey

PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED JUNE 8, 2017 NEW ISSUE - BOOK-ENTRY-ONLY RATING: Standard & Poor’s: “AA” (See “RATING” herein) In the opinion of McManimon, Scotland & Baumann, LLC, Bond Counsel to the County (as defined herein), pursuant to Section 103(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the "Code"), interest on the Bonds (as defined herein) is not included in gross income for federal income tax purposes and is not an item of tax preference for purposes of calculating the The County has authorized alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals and corporations. It is also the opinion of Bond Counsel, that interest on the Bonds . held by corporate taxpayers is included in "adjusted current earnings" in calculating alternative minimum taxable income for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on corporations. In addition, in the opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on and any gain from the sale of the Bonds is not includable as gross income under the New Jersey Gross Income Tax Act. Bond Counsel’s opinions described herein are given in reliance on representations, certifications of fact, and statements of reasonable expectation made by the County in its Tax Certificate (as defined herein), assume continuing compliance by the County with certain d d final. Upon the sale of the Bonds described covenants set forth in its Tax Certificate, and are based on existing statutes, regulations, administrative pronouncements and judicial decisions. See "TAX MATTERS" herein. COUNTY OF PASSAIC New Jersey $3,000,000 GENERAL OBLIGATION BONDS, SERIES 2017, consisting of: $1,500,000 COUNTY COLLEGE BONDS, SERIES 2017A and 12 of the Securities and Exchange Commission - $1,500,000 COUNTY COLLEGE BONDS, SERIES 2017B (County College Bond Act, P.L. -

Chapter 11 ) CHRISTOPHER & BANKS CORPORATION, Et Al

Case 21-10269-ABA Doc 125 Filed 01/27/21 Entered 01/27/21 15:45:17 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 22 TROUTMAN PEPPER HAMILTON SANDERS LLP Brett D. Goodman 875 Third Avenue New York, NY 1002 Telephone: (212) 704.6170 Fax: (212) 704.6288 Email:[email protected] -and- Douglas D. Herrmann Marcy J. McLaughlin Smith (admitted pro hac vice) Hercules Plaza, Suite 5100 1313 N. Market Street Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Telephone: (302) 777.6500 Fax: (866) 422.3027 Email: [email protected] [email protected] – and – RIEMER & BRAUNSTEIN LLP Steven E. Fox, Esq. (admitted pro hac vice) Times Square Tower Seven Times Square, Suite 2506 New York, NY 10036 Telephone: (212) 789.3100 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Agent UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) CHRISTOPHER & BANKS CORPORATION, et al., ) Case No. 21-10269 (ABA) ) ) (Jointly Administered) Debtors. 1 ) _______________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases and the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, as applicable, are as follows: Christopher & Banks Corporation (5422), Christopher & Banks, Inc. (1237), and Christopher & Banks Company (2506). The Debtors’ corporate headquarters is located at 2400 Xenium Lane North, Plymouth, Minnesota 55441. Case 21-10269-ABA Doc 125 Filed 01/27/21 Entered 01/27/21 15:45:17 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 22 DECLARATION OF CINDI GIGLIO IN SUPPORT OF DEBTORS’ MOTION FOR INTERIM AND FINAL ORDERS (A)(1) CONFIRMING, ON AN INTERIM BASIS, THAT THE STORE CLOSING AGREEMENT IS OPERATIVE AND EFFECTIVE AND (2) AUTHORIZING, ON A FINAL BASIS, THE DEBTORS TO ASSUME THE STORE CLOSING AGREEMENT, (B) AUTHORIZING AND APPROVING STORE CLOSING SALES FREE AND CLEAR OF ALL LIENS, CLAIMS, AND ENCUMBRANCES, (C) APPROVING DISPUTE RESOLUTION PROCEDURES, AND (D) AUTHORIZING CUSTOMARY BONUSES TO EMPLOYEES OF STORES I, Cindi Giglio, make this declaration pursuant to 28 U.S.C. -

Shop California Insider Tips 2020

SHOP CALIFORNIA INSIDER TIPS 2020 ENJOY THE ULTIMATE SHOPPING AND DINING EXPERIENCES! Exciting Shopping and Dining Tour Packages at ShopAmericaTours.com/shop-California Purchase with code ShopCA for 10% discount. Rodeo Drive 2 THROUGHOUT CALIFORNIA From revitalizing beauty services, to wine, spirits and chocolate tastings, DFS offers unexpected, BLOOMINGDALE’S complimentary and convenient benefits to its See all the stylish sights – starting with a visit to shoppers. Join the DFS worldwide membership Bloomingdale’s. Since 1872, Bloomingdale’s has program, LOYAL T, to begin enjoying members- been at the center of style, carrying the most only benefits while you travel.DFS.com coveted designer fashions, shoes, handbags, cosmetics, fine jewelry and gifts in the world. MACERICH SHOPPING DESTINATIONS When you visit our stores, you’ll enjoy exclusive Explore the U.S.’ best shopping, dining, and personal touches – like multilingual associates entertainment experiences at Macerich’s shopping and special visitor services – that ensure you feel destinations. With centers located in the heart welcome, pampered and at home. These are just of California’s gateway destinations, immerse a few of the things that make Bloomingdale’s like yourself in the latest fashion trends, hottest no other store in the world. Tourism services cuisine, and an unrivaled, engaging environment. include unique group events and programs, Macerich locations provide a variety of benefits special visitor offers and more, available at our to visitors, including customized shopping, 11 stores in California including San Francisco experiential packages, visitor perks and more. Centre, South Coast Plaza, Century City, Beverly To learn more about Macerich and the exclusive Center, Santa Monica Place, Fashion Valley and visitor experiences, visit macerichtourism.com. -

Millard Sheets Was Raised and Became Sensitive to California’S Agricultural Lifestyle

YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY I A A R R N T O F C I L L U A B C CALIFORNIA ART CLUB NEWSLETTER Documenting California’s Traditional Arts Heritage for More Than 100 Years e s 9 t a 9 0 b lis h e d 1 attracted 49,000 visitors. It was in this rural environment that Millard Sheets was raised and became sensitive to California’s agricultural lifestyle. Millard Sheets’ mother died in childbirth. His father, John Sheets, was deeply distraught and unable to raise his son on his own. Millard was sent to live with his maternal grandparents, Louis and Emma Owen, on their neighbouring horse ranch. His grandmother, at age thirty-nine, and grandfather, at age forty, were still relatively young. Additionally, with two of their four youngest daughters, ages ten and fourteen, living at home, family life appeared normal. His grandfather, whom Millard would call “father,” was an accomplished horseman and would bring horses from Illinois to race against Elias Jackson “Lucky” Baldwin (1828-1909) at Baldwin’s “Santa Anita Stable,” later to become Santa Anita Park. The older of Millard’s two aunts babysat him and kept him occupied Abandoned, 1934 with doing drawings. Oil on canvas 39 5/80 3 490 Collection of E. Gene Crain he magic of making T pictures became a fascination to Sheets, as he would later explain in Millard Sheets: an October 28, 1986 interview conducted A California Visionary by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian by Gordon T. McClelland and Elaine Adams Institution: “When I was about ten, I found out erhaps more than any miles east of downtown Los Angeles.