Studies of Less Familiar Birds Iy6 Barred Warbler D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

Does Experimentally Simulated Presence of a Common Cuckoo (Cuculus Canorus) Affect Egg Rejection and Breeding Success in the Red‑Backed Shrike (Lanius Collurio)?

acta ethologica (2021) 24:87–94 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10211-021-00362-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Does experimentally simulated presence of a common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) affect egg rejection and breeding success in the red‑backed shrike (Lanius collurio)? Piotr Tryjanowski1,2 · Artur Golawski3 · Mariusz Janowski1 · Tim H. Sparks1,4 Received: 23 September 2020 / Revised: 18 January 2021 / Accepted: 10 February 2021 / Published online: 8 March 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Providing artifcial eggs is a commonly used technique to understand brood parasitism, mainly by the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus). However, the presence of a cuckoo egg in the host nest would also require an earlier physical presence of the common cuckoo within the host territory. During our study of the red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio), we tested two experimental approaches: (1) providing an artifcial “cuckoo” egg in shrike nests and (2) additionally placing a stufed common cuckoo with a male call close to the shrike nest. We expected that the shrikes subject to the additional common cuckoo call stimuli would be more sensitive to brood parasitism and demonstrate a higher egg rejection rate. In the years 2017–2018, in two locations in Poland, a total of 130 red-backed shrike nests were divided into two categories: in 66 we added only an artifcial egg, and in the remaining 64 we added not only the egg, but also presented a stufed, calling common cuckoo. Shrikes reacted more strongly if the stufed common cuckoo was present. However, only 13 incidences of egg acceptance were noted, with no signifcant diferences between the locations, experimental treatments or their interaction. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Value of the Books They Review. As Such, They Are Subjective

REVIEWS EDITED BY WILLIAM E. SOUTHERN Thefollowing reviews express the opinions of theindividual reviewers regarding the strengths, weaknesses, and valueof thebooks they review. As such, they are subjective evaluations and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editorsor any officialpolicy of theA.O.U.--Eds. The growth of biological thought. Diversity, evo- tually lighter numbers of Nebelspalter!I then decided lution, and inheritance.--Ernst Mayr. 1982. Cam- that I must use "prime time," for me, 5-9 AM. This bridge, Massachusetts,Belknap Press of Harvard I did at first with reluctance,knowing that it would University Press. ix + 974 pp. $30.00.--Although slow the productivity of my laboratoryin the cur- contemporarybiologists accept, at least pro forrna, rencyof the contemporaryrealm of biosciences--the "organicevolution" as the majorunifying concept of (usuallyshort) research paper--and possibly thereby our science,surprisingly few can articulate the five constrict its cash flow. However, the more I read, the theoriesof CharlesDarwin (pp. 505-510);even fewer easier I found it to rationalize away these ominous can readily musterthe supportingevidence for and thoughts.Only time will tell if my rationalization the fallibilities of each,real or alleged.Few of us have was a grave overshoot. I doubt that it was! a clearperception of the scientific,philosophic, and This historic book can be characterizedin many socialmilieus of the mid-nineteenthcentury when ways. Depending on aspect,it is compendious,an- the historic pronouncementsof A. R. Wallace and alytical, and synthetic.The reader will soon recog- Darwin severely rattled the intellectual scaffold of nize that it is in placesselective, pontifical, and opin- Westernculture. -

Herefore Takes Precedence

Introduction I have endeavored to keep typos, errors etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2011 to: [email protected]. Grateful thanks to Dick Coombes for the cover images. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithological Congress’ World Bird List. Version Version 1.9 (1 August 2011). Cover Main image: Arctic Warbler. Cotter’s Garden, Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork, Ireland. 9 October 2009. Richard H. Coombes. Vignette: Arctic Warbler. The Waist, Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork, Ireland. 10 October 2009. Richard H. Coombes. Species Page No. Alpine Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus occisinensis] 17 Arctic Warbler [Phylloscopus borealis] 24 Ashy-throated Warbler [Phylloscopus maculipennis] 20 Black-capped Woodland Warbler [Phylloscopus herberti] 5 Blyth’s Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus reguloides] 31 Brooks’ Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus subviridis] 22 Brown Woodland Warbler [Phylloscopus umbrovirens] 5 Buff-barred Warbler [Phylloscopus pulcher] 19 Buff-throated Warbler [Phylloscopus subaffinis] 17 Canary Islands Chiffchaff [Phylloscopus canariensis] 12 Chiffchaff [Phylloscopus collybita] 8 Chinese Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus yunnanensis] 20 Claudia’s Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus claudiae] 31 Davison’s Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus davisoni] 32 Dusky Warbler [Phylloscopus fuscatus] 15 Eastern Bonelli's Warbler [Phylloscopus orientalis] 14 Eastern Crowned Warbler [Phylloscopus coronatus] 30 Emei Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus emeiensis] 32 Gansu Leaf Warbler -

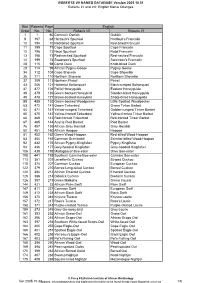

English Name Changes Bird Roberts Page Order No. No. Roberts V

ROBERTS VII NAMES DATABASE Version 2005.10.31 Roberts VI and VII: English Name Changes Bird Roberts Page English Order No. No. Roberts VII Roberts VI 1 1 60 Common Ostrich Ostrich 9 197 68 Hartlaub's Spurfowl Hartlaub's Francolin 10 194 70 Red-billed Spurfowl Red-billed Francolin 11 195 71 Cape Spurfowl Cape Francolin 12 196 72 Natal Spurfowl Natal Francolin 13 198 73 Red-necked Spurfowl Red-necked Francolin 14 199 74 Swainson's Spurfowl Swainson's Francolin 28 115 98 Comb Duck Knob-billed Duck 29 114 99 African Pygmy-Goose Pygmy Goose 34 112 108 Cape Shoveler Cape Shoveller 35 111 110 Northern Shoveler Northern Shoveller 37 109 113 Northern Pintail Pintail 43 206 121 Hottentot Buttonquail Black-rumped Buttonquail 47 477 126 Pallid Honeyguide Eastern Honeyguide 48 479 126 Green-backed Honeybird Slender-billed Honeyguide 49 478 127 Brown-backed Honeybird Sharp-billed Honeyguide 55 485 133 Green-backed Woodpecker Little Spotted Woodpecker 63 472 141 Green Tinkerbird Green Tinker Barbet 64 471 141 Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird Golden-rumped Tinker Barbet 65 470 142 Yellow-fronted Tinkerbird Yellow-fronted Tinker Barbet 66 469 143 Red-fronted Tinkerbird Red-fronted Tinker Barbet 67 465 144 Acacia Pied Barbet Pied Barbet 76 457 155 African Grey Hornbill Grey Hornbill 80 451 160 African Hoopoe Hoopoe 81 452 162 Green Wood-Hoopoe Red-billed Wood-Hoopoe 83 454 165 Common Scimitarbill Scimitar-billed Wood-Hoopoe 92 432 176 African Pygmy-Kingfisher Pygmy Kingfisher 93 436 177 Grey-headed Kingfisher Grey-hooded Kingfisher 106 439 192 Madagascar Bee-eater -

Limited Flexibility in Departure Timing of Migratory Passerines at the East

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Limited fexibility in departure timing of migratory passerines at the East‑Mediterranean fyway Yaara Aharon‑Rotman 1,2*, Gidon Perlman3, Yosef Kiat3,4, Tal Raz1, Amir Balaban3 & Takuya Iwamura1,5* The rapid pace of current global warming lead to the advancement of spring migration in the majority of long‑distance migratory bird species. While data on arrival timing to breeding grounds in Europe is plentiful, information from the African departure sites are scarce. Here we analysed changes in arrival timing at a stopover site in Israel and any links to Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) on the species‑ specifc African non‑breeding range in three migratory passerines between 2000–2017. Diferences in wing length between early and late arriving individuals were also examined as a proxy for migration distance. We found that male redstart, but not females, advanced arrival to stopover site, but interestingly, not as a response to EVI phenology. Blackcap and barred warbler did not shift arrival timing signifcantly, although the arrival of blackcap was dependent on EVI. Barred warbler from the early arrival phase had longer wings, suggesting diferent populations. Our study further supports the existence species‑specifc migration decisions and inter‑sexual diferences, which may be triggered by both exogenous (local vegetation condition) and endogenous cues. Given rapid rate of changes in environmental conditions at higher latitudes, some migrants may experience difculty in the race to match global changes to ensure their survival. Current global warming is occurring at an asymmetrical pace, with greater increase in temperatures at higher northern latitudes1,2. -

Comparison of Nest Defence Behaviour Between Two Associate Passerines

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector J Ethol (2013) 31:1–7 DOI 10.1007/s10164-012-0340-2 ARTICLE Comparison of nest defence behaviour between two associate passerines Marcin Polak Received: 20 February 2012 / Accepted: 20 July 2012 / Published online: 23 August 2012 Ó The Author(s) 2012. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Nest predation is one of the most important Introduction factors limiting reproductive success, and antipredator behaviour can significantly reduce the loss of avian broods. Recent empirical studies have suggested that positive I carried out field experiments on two sympatric passerines: interactions may be common, predictable and pervasive the barred warbler and the red-backed shrike. Many authors important forces in different ecosystems (Blanco and Tella have described the protective nature of nesting association 1997; Martin and Martin 2001; Quinn et al. 2003; Sergio between these species. However, we have little knowledge et al. 2004; van Kleef et al. 2007; Nocera et al. 2009). about the true nature of the relationships between associ- Protection of broods from predators using aggressive ates. I examined (1) whether barred warblers and red- behaviour of other species is one of the most unusual backed shrikes respond differently to an avian predator, strategies used by birds to evade predation (Clark and and (2) whether males and females differ in the intensity of Robertson 1979; Norrdahl et al. 1995). One such strategy is nest defence. Decoys of a known nest predator and a non- the creation of protective nesting associations in which one predatory control species were used to examine the types or more species relate and directly benefit from nesting and relative intensity of parental response. -

Comparative Breeding Ecology, Nest Survival, and Agonistic Behaviour Between the Barred Warbler and the Red-Backed Shrike

J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-016-1336-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Comparative breeding ecology, nest survival, and agonistic behaviour between the Barred Warbler and the Red-backed Shrike Marcin Polak1 Received: 9 October 2015 / Revised: 7 February 2016 / Accepted: 29 February 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The majority of studies have demonstrated that likely to survive in the middle of the breeding season. The the Barred Warbler Sylvia nisoria (BW) and the Red- level of aggression between the BW and RBS was low, as backed Shrike Lanius collurio (RBS), where they occur demonstrated by experiments with stuffed models; this was sympatrically in central Europe, inhabit similar niches and a factor in favour of their nesting in close proximity to one are not averse to nesting in each other’s vicinity. The another. present work compares the reproductive parameters, nest survival, and behavioural interactions between these two Keywords Species co-existence Á Protective nesting ecologically similar species. The study was carried out in association Á Positive interactions Á Nest survival eastern Poland in two types of habitat: a river valley and farmland. Inter-habitat analysis showed both species to Zusammenfassung have similar reproductive parameters, although nest sur- vival of the RBS was greater in farmland than in the river Vergleichende Brutbiologie, Nesterfolg und agonisti- valley. Interspecific comparison revealed that the BW built sches Verhalten zwischen Sperbergrasmu¨cken und smaller nests, laid fewer and smaller eggs than the RBS, Neunto¨tern but the production of offspring was similar in both species. -

Protective Nesting Association Between the Barred Warbler Sylvia Nisoria and the Red-Backed Shrike Lanius Collurio: an Experiment Using Artificial and Natural Nests

Ecol Res DOI 10.1007/s11284-014-1183-9 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Marcin Polak Protective nesting association between the Barred Warbler Sylvia nisoria and the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio: an experiment using artificial and natural nests Received: 4 March 2014 / Accepted: 2 July 2014 Ó The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The pressure of predators may significantly (Bronstein 1994). Positive interactions are ubiquitous in affects the distribution pattern of nesting birds. Some natural communities (Herre et al. 1999), although it is individuals may reduce the risk of predation by nesting now widely recognized that they have been relatively near other species with an aggressive nest defence. In the ignored by researchers who focused almost exclusively present study I tested the predator protection hypothesis on competition and predation (Bronstein 2009). In re- using experimental (artificial nests) and observational cent years cooperation and helping between unrelated (real nests) approaches on two ecologically similar pas- individuals is one of the key topics in evolutionary serine birds–the Barred Warbler Sylvia nisoria and the biology (Quinn and Ueta 2008; Bshary and Bronstein Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio. Studies have been 2011). A model example of positive interaction is the conducted in eastern Poland in two types of habitat: formation of protective nesting association (Bogliani river valley and farmland. The main predators of natural et al. 1999; Richardson and Bolen 1999). In their at- and artificial nests were birds, and to a lesser extent, also tempts to minimise nest predation, animals actively seek mammals. I found wide variation level of predation of out individuals of an accompanying species nesting both types of nests in different years. -

Supplementary Material

Sylvia nisoria (Barred Warbler) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 4 Sources of reported national population data p. 6 Species factsheet bibliography p. 10 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Sylvia nisoria (Barred Warbler) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term population trend4