The Development of Fisheries in Jamaica : Report of a Pre-Feasibility1 Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Make It Easier for You to Sell

We Make it Easier For You to Sell Travel Agent Reference Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE ITEM PAGE Accommodations .................. 11-18 Hotels & Facilities .................. 11-18 Air Service – Charter & Scheduled ....... 6-7 Houses of Worship ................... .19 Animals (entry of) ..................... .1 Jamaica Tourist Board Offices . .Back Cover Apartment Accommodations ........... .19 Kingston ............................ .3 Airports............................. .1 Land, History and the People ............ .2 Attractions........................ 20-21 Latitude & Longitude.................. .25 Banking............................. .1 Major Cities......................... 3-5 Car Rental Companies ................. .8 Map............................. 12-13 Charter Air Service ................... 6-7 Marriage, General Information .......... .19 Churches .......................... .19 Medical Facilities ..................... .1 Climate ............................. .1 Meet The People...................... .1 Clothing ............................ .1 Mileage Chart ....................... .25 Communications...................... .1 Montego Bay......................... .3 Computer Access Code ................ 6 Montego Bay Convention Center . .5 Credit Cards ......................... .1 Museums .......................... .24 Cruise Ships ......................... .7 National Symbols .................... .18 Currency............................ .1 Negril .............................. .5 Customs ............................ .1 Ocho -

… Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/RW/EBSA/WCAR/1/2

CBD Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/RW/EBSA/WCAR/1/2 23 February 2012 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH WIDER CARIBBEAN AND WESTERN MID-ATLANTIC REGIONAL WORKSHOP TO FACILITATE THE DESCRIPTION OF ECOLOGICALLY OR BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT MARINE AREAS Recife, Brazil, 28 February –2 March 2012 COMPILATION OF SUBMISSIONS OF SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION TO DESCRIBE EBSAS IN THE WIDER CARIBBEAN AND WESTERN MID-ATLANTIC REGION Note by the Executive Secretary 1. The Executive Secretary is circulating herewith a compilation of submissions of scientific information to describe ecologically or biologically significant marine areas (EBSAs) in the Wider Caribbean and Western Mid-Atlantic region, submitted by Parties and organizations in response to notification 2012-001, dated 3 January 2012, for the information of participants in the Wider Caribbean and Western Mid-Atlantic Regional Workshop to Facilitate the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas, being convened by the Convention on Biological Diversity and hosted by the Government of Brazil in Recife, Brazil, from 28 February to 2 March 2012, in collaboration with the Caribbean Environment Programme (CEP), with financial support from the European Union. 2. This compilation consists of the following: (a) A list of submissions made by Parties and organizations. The original submissions are available athttp://www.cbd.int/doc/?meeting=RWEBSA-WCAR-01. The list is divided into two parts: the first table contains submissions of potential areas that meet EBSA criteria, most utilizing the template provided for that purpose in the above notification; the second consists of supporting documentation; and (b) A background document entitled "Data to inform the Wider Caribbean and Western Mid- Atlantic Regional Workshop to Facilitate the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas”, which was prepared by the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab, Duke University, with financial support from the European Union, in support of the CBD Secretariat in its technical preparation for the above-mentioned regional workshop. -

ABSTRACT a Preliminary Natural Hazards Vulnerability Assessment

1 ABSTRACT A Preliminary Natural Hazards Vulnerability Assessment of the Norman Manley International Airport and its Access Route Kevin Patrick Douglas M.Sc. in Disaster Management The University of the West Indies 2011 The issue of disaster risk reduction through proper assessment of vulnerability has emerged as a pillar of disaster management, a paradigm shift from simply responding to disasters after they have occurred. The assessment of vulnerability is important for countries desiring to maintain sustainable economies, as disasters have the potential to disrupt their economic growth and the lives of thousands of people. This study is a preliminary assessment of the hazard vulnerabilities the Norman Manley International Airport (NMIA) in Kingston Jamaica and its Access Route, as these play an important developmental role in the Jamaican society. The Research involves an analysis of the hazard history of the area along with the location and structural vulnerabilities of critical facilities. Finally, the mitigation measures in place for the identified hazards are assessed and recommendations made to increase the resilience of the facility. The findings of the research show that the NMIA and its access route are mostly vulnerable to earthquakes, hurricanes with flooding from storm surges, wind damage and sea level rise based 2 on their location and structure. The major mitigation measures involved the raising of the Access Route from Harbour View Roundabout to the NMIA and implementation of structural protective barriers as well as various engineering design specifications of the NMIA facility. Also, the implementation of structural mitigation measures may be of limited success, if hazard strikes exceed the magnitude which they are designed to withstand. -

Jamaica Tourist Everything You Need to Know for the Perfect Vacation Experience

JAMAICA TOURIST WWW.JAMAICATOURIST.NET EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW FOR THE PERFECT VACATION EXPERIENCE ISSUE 14 - SPRING 2010 IN THIS ISSUE JOSS STONE SHINES AT 2010 JAMAICA JAZZ & BLUES FESTIVAL FANTASTIC GOLF EXPLORING JAMAICA THE ‘ONE LOVE’ PROJECT PALMYRA OWNERS TAKE OCCUPANCY OF LUXURY RESIDENCES CHULANI’S REMARKABLE JOURNEY TO JAMAICA HISTORIC TRAMWAYS OF KINGSTON THE GAP CAFÉ - JEWEL IN THE BLUE MOUNTAINS CUISINE FOR EVERY TASTE SHOPPING PAR EXELLENCE WHAT A GWAAN? OWN A TROPICAL HOME AT THE PALMYRA Look for the FREE GEMSTONE offer in the YOUR luxury shopping section! FREE ISSUE SEE ISLAND MAP INSIDE GROOVIN’ IN JAMAICA eople visit Jamaica for many reasons, one of which is the island’s many world-class music festivals that include Reggae Sumfest, Rebel Salute, Sting and perhaps the most popular, Jamaica Jazz & Blues Festival. From January 28 - 30, more than 20,000 Jazz and Blues aficionados flocked the lawns of the PTrelwany Multipurpose Stadium in Greenfield, for the 14th staging of the trendy event. Staged at the stadium for the first time this year, most skeptics were quickly won over by the ease of access and superior parking facilities of the venue, which comfortably hosted VIP tents, skyboxes, a craft market and a wide variety of food & beverage outlets. Combined with the world-class music line-up and masses of happy music lovers, the stadium formed a perfect venue. Visited by thousands of people at its former home Is This Love. Next, singer and songwriter Kenny ‘Babyface’ Edmonds entered the stage with a band dressed in at the iconic aqueduct of Rose Hall, the Jazz & Blues black tuxedos and paid homage to the ‘many beautiful women of Jamaica’ with classics like Every Time I Close Festival has seen outstanding performances by major My Eyes and My My My, Mama, Can We Talk For A Minute and I Wanna Rock With You Baby. -

Fully Examined to Identify Cryptic Predators

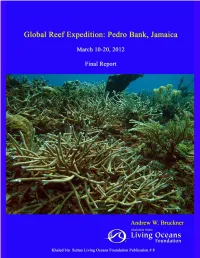

Front cover: Photo by Andrew Bruckner. Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation 8181 Professional Place Landover, MD, 20785 USA Philip G. Renaud, Executive Director http://www.livingoceansfoundation.org All research was performed under a permit obtained from the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA) (ref #18/27, 8 December, 2011). No animals or plants were collected during the research project. No animals were killed or injured during the execution of the project, and no injured or dead marine mammals or turtles were observed. No oil spills occurred from the M/Y Golden Shadow or any of the support vessels, and oil slicks were not observed. The Golden Shadow used a single anchorage during the mission located behind Southwest Cay. The Golden Shadow provided potable water to the fishers living on Middle Cay. The information in this Final Report summarizes the outcomes of the research conducted during the March, 2012, as part of the Global Reef Expedition, to Pedro Bank Jamaica. Information presented in the report includes general methods, the activities conducted during the mission, general trends and observations, analyzed data and findings, and recommendations. The Living Oceans Foundation cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors. June 1, 2013. Citation: Bruckner, A. (2013) Global Reef Expedition: Pedro Bank, Jamaica. March 10-20, 2012. Final Report. Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation Publication #8, Landover MD. pp. 94. The Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation (KSLOF) was incorporated in California as a 501(c)(3), public benefit, Private Operating Foundation in September 2000. KSLOF headquarters are in Washington DC. -

Guide Welcome Irie Isle

GUIDE WELCOME IRIE ISLE Seven Mile Beach Seven Mile Beach KNOWN FOR ITS STUNNING BEAUTY, Did you know? The traditional cooking technique FRIENDLY PEOPLE, LAND OF WOOD AND WATER known as jerk is said to have been invented by the island’s Maroons, VIBRANT CULTURE or runaway slaves. AND RICH HISTORY, Jamaica is a destination so dynamic and multifaceted you could visit hundreds of Negril, Frenchman’s Cove in Portland, Treasure Beach on the South Coast or the times and have a unique experience every single time. unique Dunn’s River Falls and Beach in Ocho Rios, there’s a beach for everyone. THERE’S NO BETTER Home of the legendary Bob Marley, arguably reggae’s most iconic and globally But if lounging on the sand all day is not your style, a visit to Jamaica may be recognised face, the island’s most popular musical export is an eclectic mix of just what the doctor ordered. With hundreds of fitness facilities and countless WORD TO DESCRIBE infectious beats and enchanting — and sometimes scathing — lyrics that can be running and exercise groups, the global thrust towards health and wellness has THE JAMAICAN heard throughout the island. The music is also celebrated through annual festivals spawned annual events such as the Reggae Marathon and the Kingston City such as Reggae Sumfest and Rebel Salute, where you could also indulge in Run. The get-fit movement has also influenced the creation of several health and EXPERIENCE Jamaica’s renowned culinary treats. wellness bars, as well as spa, fitness and yoga retreats at upscale resorts. -

Resu Its of Troll Fish Ing Explorations in the Caribbean

Sta- Dominant Sta· Dominant Sta- Dominant tlon Buckets species tlon Buckets Species tlon Buckets Species Martinique Tnnldad Fort-de-France 6 335 AN Chaguaramas Bay 11 1,055 .0 SA , TH Port Antonio 40 SI Port Royal Grande Anses d 'Arlet 4 350 SA , SI , Chupara Bay 4 2470 SA 1 100 AN RS Port 01 Spain Ha rbor 3 500 PL Port Royal Cays 3 1020 DH , SI Port Royal Mangrove St .-Pierre 2 130 RS La s Cuevas Bay 60 PL 45 0 AN St Lucia Lampara Net Dominican Republic Anse ChOiseul 30.0 PL, TH Jamaica Bah ia de Semana 305 AN Caralbe POint 5.0 SA East Kingston 2 520 AN Venezuela Castnes Harbor 0.5 AN Li me Cay 150 SI Islas Los Roques 870 SI Gros Islet Bay 1 05 Mi xed Port Royal 0 CuraGao Mangot Bay 3 145 AN Domin ica n Republic Pl aza Abao 5 0 RS Pet it Tr ou 1 0 Bah ia de Ocoa 2 1250 PL , TH Portanare Bay 35 SI Roseau Bay 3 88 5 SA , TH Boca del Yuma 0 I AN = anchovy (Engraulldae) Soulnere Bay 1 25.5 SI Saona Island 0 DH = dwarf herring (Jenklnsla) Vleux Fort 5 13.5 TH Jamaica PL = pilchards (Harengula) Tobago lime Cay 1 120 DH RS = round scad (Decapterus) Great Courland Bay 10 Long Ba y 1 80 AN SA = sardine (Sardlneita) Man-ol-War Bay 890 RS Negr" Harbor 2 2 .0 AN SI = sllversldes (Athennld ae) Rockly Bay 30 PL Pigeon Island 700 DH TH = thread herring (O p isthonema) MFR Paper 1084 From Manne Flshenes Review, Vol. -

1 NATIONAL MONUMENTS CLARENDON Buildings Of

NATIONAL MONUMENTS CLARENDON Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest Halse Hall Great House (Declared 28/11/2002) Churches, Cemeteries, Tombs St. Peter’s Church, Alley (Declared 30/03/2000) Clock Towers May Pen Clock Tower (Declared 15/03/2001) Natural Sites Milk River Spa (Declared 13/09/1990) HANOVER Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest Barbican Estate (Declared 16/12/1993) Tamarind Lodge (Declared 15/07/1993) Old Hanover Gaol/Old Police Barracks, Lucea (Declared 19/03/1992) Tryall Great House and Ruins of Sugar Works (Declared 13/09/1990) Forts and Naval and Military Monuments Fort Charlotte, Lucea (Declared 19/03/1992) Historic Sites Blenheim – Birthplace of National Hero – The Rt. Excellent Sir Alexander Bustamante (Declared 05/11/1992) KINGSTON Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest 40 Harbour Street (Declared 10/12/1998) Headquarters House, Duke Street (Declared 07/01/2000) Kingston Railway Station, Barry Street (Declared 04/03/2003) The Admiralty Houses, Port Royal (Declared 05/11/1992) Churches, Cemeteries, Tombs Coke Methodist Church, East Parade (Declared 07/01/2000) East Queen Street Baptist Church, East Queen Street (Declared 29/10/2009) Holy Trinity Cathedral, North Street (Declared 07/01/2000) Kingston Parish Church, South Parade (Declared 04/03/2003) Wesley Methodist Church, Tower Street (Declared 10/12/1998) Old Jewish Cemetery, Hunts Bay (Declared 15/07/1993) 1 Forts and Naval and Military Monuments Fort Charles, Port Royal (Declared 31/12/1992) Historic Sites Liberty Hall, 76 King Street (Declared 05/11/1992) Public Buildings Ward Theatre, North Parade (Declared 07/01/2000) Statues and Other Memorials Bust of General Antonio Maceo, National Heroes Park (Declared 07/01/2000) Cenotaph, National Heroes Park (Declared 07/01/2000) Negro Aroused, Ocean Boulevard (Declared 13/04/1995) Monument to Rt. -

Ecologically Or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (Ebsas) Special Places in the World’S Oceans

2 Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs) Special places in the world’s oceans WIDER CARIBBEAN AND WESTERN MID-ATLANTIC Areas described as meeting the EBSA criteria at the CBD Wider Caribbean and Western Mid-Atlantic Regional Workshop in Recife, Brazil, 28 February to 2 March 2012 Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. ISBN: 92-9225-560-6 Ecologically or Copyright © 2014, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression Biologically Significant of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Marine Areas (EBSAs) The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Special places in the world’s oceans The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsi ble for Areas described as meeting the EBSA criteria at the any use which may be made of the information contained therein. CBD Wider Caribbean and Western Mid-Atlantic Regional This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Secretariat of the Convention on Workshop in Recife, Brazil, 28 February to 2 March 2012 Biological Diversity would appreciate receiving a copy of any publications that use this document as a source. -

Copyrighted Material

Apartment rentals, 58 Bluefields Bay, 158 Index Appleton Rum Estate, Bluefields Beach Park, 158 163–164 The Blue Lagoon, 224 GENERAL INDEX See also Accommodations and Aquasol Theme Park Blue Mountain Bicycle Tours Restaurant indexes, below. (Montego Bay), 108 Ltd., 52, 259–260 Architecture, 18–20 Blue Mountain coffee, 36 Area code, 267 Blue Mountain-John Crow Art, 17–18 Mountain National Park, General Index Art galleries 259 A Kingston, 253 Blue Mountain Peak, 266 A&E Pharmacy (Port Montego Bay, 117 The Blue Mountains, 64, 238 Antonio), 212 Ocho Rios, 200 exploring, 259–266 Abbey Green, 265–266 Port Antonio, 236 Blue Mountain Sunrise Tour, The Absolute Temptation Asylum (Kingston), 254 260 Isle (Negril), 40 At Home Abroad, 58 Blue Mountain Tours, 198 Accommodations, 57–59. ATMs (automated-teller Boating and sailing (rentals See also Accommodations machines), 47–48 and charters), Negril, 149 Index Attractions Link (Port Bob Marley Birthday Bash best, 4–7 Antonio), 235 (Montego Bay), 39 Bluefields, 157–158 Australia Bob Marley Centre & Falmouth, 121 customs regulations, 42 Mausoleum (Nine Mile), Kingston, 240–245 passports, 268 207 Mandeville, 169–170 Bob Marley Museum Montego Bay, 90–101 (Kingston), 252 B Bob Marley Week all-inclusive resorts, Bamboo Avenue (Middle 97–101 (Kingston), 39 Quarters), 163 Bonney, Ann, 152 reservations, 90 Bananas, 219 Newcastle, 262 Books, recommended, Banks 27–28 Ocho Rios, 175–185 Kingston, 239 Port Antonio, 212–218 Bookstores Mandeville, 169 Montego Bay, 88 Port Royal, 257–258 Negril, 128 Treasure Beach, 164–166 Ocho Rios, 174 Ocho Rios, 174 Boston Bay Beach (Port Whitehouse, 160 Port Antonio, 212 Accompong Maroon Festival Antonio), 225, 227 Baptist Manse (Falmouth), Boundbrook Wharf (Port (St. -

1 NATIONAL MONUMENTS CLARENDON Buildings Of

NATIONAL MONUMENTS CLARENDON Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest Halse Hall Great House (Declared 28/11/2002) Churches, Cemeteries, Tombs St. Peter’s Church, Alley (Declared 30/03/2000) St. Paul’s Anglican Church, Chapelton (Declared 17/03/2016) Clock Towers May Pen Clock Tower (Declared 15/03/2001) Chapelton Clock Tower (Declared 28/03/2017) Natural Sites Milk River Spa (Declared 13/09/1990) Statues and Other Memorials Bust of Cudjoe, Chapelton (Declared 28/03/2017) Claude McKay Marker, James Hill (Declared 05/03/2019) HANOVER Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest Barbican Estate (Declared 16/12/1993) Lucea Town Hall & Clock Tower (Declared 19/03/2013) Tamarind Lodge (Declared 15/07/1993) Old Hanover Gaol/Old Police Barracks, Lucea (Declared 19/03/1992) Tryall Great House and Ruins of Sugar Works (Declared 13/09/1990) Churches, Cemeteries, Tombs Hanover Parish Church (Declared 28/03/2013) Forts and Naval and Military Monuments Fort Charlotte, Lucea (Declared 19/03/1992) Historic Sites Blenheim – Birthplace of National Hero – The Rt. Excellent Sir Alexander Bustamante (Declared 05/11/1992) Sugar & Coffee Works Kenilworth Ruins (Declared 19/042018) 1 KINGSTON Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest 40 Harbour Street (Declared 10/12/1998) 150 East Street (Declared 28/03/2017) Headquarters House, Duke Street (Declared 07/01/2000) Kingston Railway Station, Barry Street (Declared 04/03/2003) The Admiralty Houses, Port Royal (Declared 05/11/1992) Old Mico Building, Hanover Street (Declared 07/04/2016) Churches, Cemeteries, Tombs Coke Methodist Church, East Parade (Declared 07/01/2000) East Queen Street Baptist Church, East Queen Street (Declared 29/10/2009) Holy Trinity Cathedral, North Street (Declared 07/01/2000) Kingston Parish Church, South Parade (Declared 04/03/2003) Wesley Methodist Church, Tower Street (Declared 10/12/1998) Old Jewish Cemetery, Hunts Bay (Declared 15/07/1993) St. -

Protected Areas System Master Plan: Jamaica 2013 – 2017

Protected Areas System Master Plan: Jamaica 2013 – 2017 Final Submission to the Protected Areas Committee Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Background ........................................................................................................................................................... 15 1.1 Rationale for Jamaica’s Protected Areas System Master Plan .................................................................. 15 1.1.1 Coherence in Protected Areas Management .................................................................................... 15 1.1.2 Benefits of a System Approach .......................................................................................................... 15 1.1.3 Linkages to National Plans and Strategies ......................................................................................... 17 1.1.4 Meeting International