This Work Is Protected by Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DECEMBER 2015 Page 1 Editorial: Handcarts in Convoy

NEWSLETTER Editorial – 2 General practice on the brink – 4 Junior doctors: the wider view– 5 Barts merger nightmare – 7 Manslaughter and beyond – 8 AGM and Conference 2015 – 11-21 AGM: Reports – 12 AGM: General practice – 14 AGM: New politics – 16 AGM: Devo-Manc – 17 Git et qui nonAGM: et ommollesFYFV – 18 corempo AGM: Devolution – 19 AGM: Paul Noone Memorial Lecture – 20 Mental health: What lies ahead – 22 Executive Committee 2015-16 – 24 Page 1 DECEMBER 2015 Page 1 Editorial: Handcarts in convoy Despite 70 years of continual old- and (as someone else pointed out testament-worthy predictions of when they highlighted the high-risk terminal melt-down, the NHS government strategy of targeting the arrives, join our happy team” – the won’t do that, just as it hasn’t juniors) very definitely neither on usual depressing PR-speak. since 1948. We’d do well not to the golf course nor seeing private Interestingly, many of the trusts were proclaim its demise – a ritual patients. I spoke to a couple of – though you’d never know it looking pronouncement every winter. foundation year doctors. They told at the pictures of happy-clappy But its foundations continue me of their concerns for patient healthcare professionals – in special to be eroded in ways that safety, their insecurity about their measures or otherwise engaged only intermittently make the long-term futures, and the instability with the CQC, so were obeying the headlines. Without seeking out of their organisations. By the time management-consultant mantra of trouble – or even information, for this is in print, they will either have smiling especially broadly when you’re that matter – in the past couple become the 2015 equivalents of in your death throes, and hoping of weeks several of the demons the miners under Mrs Thatcher, or that some people might not notice gave me a good nip. -

This Book Compares Resistance to Technology Across Time, Nations and Tech- Nologies

This book compares resistance to technology across time, nations and tech- nologies. Three post-war technologies - nuclear power, information technology and biotechnology - are used in the analysis. The focus is on post-1945 Europe, with comparisons made with the USA, Japan and Australia. Instead of assuming that resistance contributes to the failure of a technology, the main thesis of this book is that resistance is a constructive force in technological development, giving technology its particular shape in a particular context. Whilst many people still believe in science and technology, many have become more sceptical of the allied 'progress'. By exploring the idea that modernity creates effects that undermine its own foundations, forms and effects of resistance are explored in various contexts. The book presents a unique interdisciplinary study, including contributions from historians, sociologists, psychologists and political scientists. Resistance to new technology Resistance to new technology nuclear power information technology and biotechnology edited by MARTIN BAUER The National Museum WigRTof Science & Industry Science Museum 31 CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building. Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1995 This book is in copyright. -

Trade Union Collective Identity, Mobilisation and Leadership – a Study of the Printworkers’ Disputes of 1980 and 1983

Trade Union collective identity, mobilisation and leadership – a study of the printworkers’ disputes of 1980 and 1983 Nigel Costley 1 2 University of the West of England Collective identity and strategic choice – a study of the printworkers’ disputes of 1980 and 1983 Nigel Costley A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bristol Business School, University of the West of England 2021 3 Declaration I declare that this research thesis is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Nigel Costley Date 4 Copyright This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements Thanks to Professor Stephanie Tailby, Professor Sian Moore and Dr Mike Richardson for their continuous encouragement, support and constructive criticisms. 5 Abstract The National Graphical Association (NGA) typified the British model of craft unionism with substantial positional power and organisational strength. This study finds that it relied upon, and was reinforced by, the common occupational bonds that members identified with. It concludes that the value of collective identity warrants greater attention in the debate over union renewal alongside theories around mobilisation and organising (Kelly 2018), alliance-building and social movements (Holgate 2014). Sectionalism builds solidarity through the exclusion of others. Occupational identity is vulnerable to technological change. This model neglects institutional and ‘associational’ power, eschewing legal protections in favour of collective bargaining and ignoring alliance-building in favour of sovereign authority. -

Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers

ID Heading Subject Organisation Person Industry Country Date Location 74 JIM GARDNER (null) AMALGAMATED UNION OF FOUNDRY WORKERS JIM GARDNER (null) (null) 1954-1955 1/074 303 TRADE UNIONS TRADE UNIONS TRADES UNION CONGRESS (null) (null) (null) 1958-1959 5/303 360 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS (null) (null) (null) 1942-1966 7/360 361 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NOW ASSOCIATIONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1967 TO 7/361 362 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS CONFERENCES NONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1955-1966 7/362 363 ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS APPRENTICES ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS (null) EDUCATION (null) 1964 7/363 364 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1929-1935 7/364 365 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1935-1962 7/365 366 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1963-1970 7/366 367 BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) TRANSPORT CIVIL AVIATION (null) 1969-1970 7/367 368 CHEMICAL WORKERS UNION CONFERENCES INCOMES POLICY RADIATION HAZARD -

Congress Report 2006

Congress Report 2006 The 138th annual Trades Union Congress 11-14 September, Brighton 4 Contents Page General Council members 2006 – 2007……………………………… .............4 Section one - Congress decisions………………………………………….........7 Part 1 Resolutions carried.............................. ………………………………………………8 Part 2 Motion remitted………………………………………………… ............................28 Part 3 Motions lost…………………………………………………….. ..............................29 Part 4 Motion withdrawn…………………………………………………………………….29 Part 5 General Council statements…………………………………………………………30 Section two – Verbatim report of Congress proceedings .....................35 Day 1 Monday 11 September ......................................................................................36 Day 2 Tuesday 12 September……………………………………… .................................76 Day 3 Wednesday 13 September...............................................................................119 Day 4 Thursday 14 September ...................................................................................159 Section three - unions and their delegates ............................................183 Section four - details of past Congresses ...............................................195 Section five - General Council 1921 – 2006.............................................198 Index of speakers .........................................................................................203 General Council Members Mark Fysh UNISON 2006 – 2007 Allan Garley GMB Bob Abberley Janice Godrich UNISON Public and Commercial -

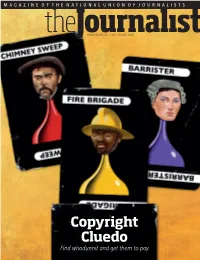

Copyright Cluedo Find Whodunnit and Get Them to Pay Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | JULY-AUGUST 2018 Copyright Cluedo Find whodunnit and get them to pay Contents Main feature 12 Close in and win The quest for copyright justice News opyright has been under sustained 03 STV cuts jobs and closes channel attack in the digital age, whether it is through flagrant breaches by people Pledge for no compulsory redundancies hoping they can use photos and 04 Call for more disabled people on TV content without paying or genuine NUJ backs campaign at TUC conference Cignorance by some who believe that if something is downloadable then it’s free. Photographers 05 Legal action to demand Leveson Two and the NUJ spend a lot of time and energy chasing copyright. Victims get court go-ahead This edition’s cover feature by Mick Sinclair looks at a range of 07 Al Jazeera staff win big pay rise practical, good-spirited ways of making sure you’re paid what Deal reached after Acas talks you’re owed. It can take a bit of detective work. Data in all its forms is another big theme of this edition. “Whether it’s working within the confines of the new general Features data protection regulations or finding the best way to 10 Business as usual? communicate securely with sources, data is an increasingly What new data rules mean for the media important part of our work. Ruth Addicott looks at the implications of the new data laws for journalists and Simon 13 Safe & secure Creasey considers the best forms of keeping communication How to communicate confidentially with sources private. -

Modern Records Centre Annual Report 2014-2015 2 Modern Records Centre Introduction

Modern Records Centre Annual Report 2014-2015 2 Modern Records Centre Introduction 2014-2015 has been an action packed year. We have developed links and projects with new and different audiences and researchers, extending our educational work and introducing many more students and schools to the archives we hold. Nuala’s Archives aLive project was particularly exciting and certainly enthused some of our younger visitors. The Centre also started to work with the Students Union on a series of talks and exhibitions and this has provided a foundation for a programme of events which we hope to develop in the next academic year. Details on all of these activities are included in this report. The fiftieth anniversary placed significant demands on the Centre and provided impetus for the digitisation of large amounts of the University’s material including many photographs and student publications. Our front cover this year shows the building of the main Library in June 1966 and highlights the dramatic changes which have occurred to the Warwick campus over the 50 years. We have delivered talks to external audiences, hosted exhibitions and even took part in the Cheltenham Science Festival alongside Warwick’s Science Faculty with tea, cake and photographs of our LEO computer material (suitably protected). An interesting and eventful year! Annual Report 2014/15 3 Collections/Accessions We received 62 deposits during the year ranging in size from a few items to several hundred boxes. Some of the highlights are listed below. By far the largest deposit during the year was the archive of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain, which arrived in March 2015 and fills well over 400 boxes. -

Revue Française De Civilisation Britannique, XXII- Hors Série | 2017 Britain in the Seventies – Our Unfinest Hour? 2

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XXII- Hors série | 2017 The United Kingdom and the Crisis in the 1970s Britain in the Seventies – Our Unfinest Hour? Les années 1970- le pire moment de l'histoire britannique? Kenneth O. Morgan Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/1662 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.1662 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Electronic reference Kenneth O. Morgan, “Britain in the Seventies – Our Unfinest Hour?”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XXII- Hors série | 2017, Online since 30 December 2017, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/1662 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb. 1662 This text was automatically generated on 21 September 2021. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Britain in the Seventies – Our Unfinest Hour? 1 Britain in the Seventies – Our Unfinest Hour? Les années 1970- le pire moment de l'histoire britannique? Kenneth O. Morgan 1 In popular recollection, the 1970s have gone down as the dark ages, Britain’s gloomiest period since the Second World War. It may be that the aftermath of the Brexit vote in 2016 will herald a period of even greater crisis, but for the moment the sombre seventies, set between Harold Wilson’s ‘swinging sixties’ and Margaret Thatcher’s divisive eighties, stand alone. They began with massive trade union stoppages against Heath’s Industrial Relations Act. -

Regional Feelings Prevail in Nuneaton, Near Birmingham

FROM THE LONDON END them in the third by-election result Regional Feelings Prevail in Nuneaton, near Birmingham. Here the young Labour successor to the IN A remarkable analogy to recent ment's economic and industrial pro- former Labour Minister and leader trends in India, this week's "mini- gramme for the regional develop- of the left wing Transport Workers election" in Britain has shown ment areas to reverse this trend. Union, Frank Cousins, managed to strong support for regionalism. The The fact now is that no seat in hold the seat with a majority re- Wilson Government will now have either Scotland or Wales is now safe duced from 11,000 to 4,000. to seriously consider decentralising from Nationalist raiding parties. In The Liberals polled a respectable Government within the United terms of the United Kingdom Par- 7,600 votes—an increase on their Kingdom if it is to withstand the liament this represents a serious showing in the 1966 general election. rising tide of nationalist opinion in threat to Labour's majority which It seems where there are no region- Scotland and Wales. is heavily dependent on Scottish al or nationalist elements at work and Welsh seats. and where there is no recognised It is fashionable to attribute the left alternative for frustrated Labour Labour Party's failure in the Glas- It must also be said, however, that voters, the Liberals can still make gow, Pollock election and the heavy the Scottish and Welsh nationalist ground. They recognise, however, drop in vote in the former Labour manifestations are not identical. -

Scanned Image

i' . ' - _‘ . I | . r advocates of trade union? ndependence ’ .. \ and socialist structural reforms. Today, no-one on the Left can fail to see the drift of the Wilson administration. It was no left-winger, but Beg Paget, who rightly likened the new Bill to the Statute of Labourers, which directly provoked Jack Cade's Rebellion. Even more appositely, Ian Mikardo has char- acterised it as a horse out of Mussolini's stable. The whole measure can only be construed as the culminating attack in a whole series of forays against the basic freedom of Labour in this country. Of course, Frank Cousins is entirely right to insist that events in Westminster will not determine the fate of Benito Brown's new Bill. But this fact should not make socialists indifferent to events in Parl- iament. The factories will decide the —.v— _ issue, but they will decide it much more A NEWS ANALYSIS FOR SOCIALISTS effectively if, from the beginning, there is serious political resistance, The mutineers in Parliament can act as a focal lens, through which the mounting trade union discontent can be brought to white Stand Fasti Fight the Mussolini Labour Laws I heat at the exact point where it can be effective. As we go to press, two dozen members of Parl- Out of Parliament, many unions are already iament on the Labour back benches have just taking preparatory steps to meet the new abstained for the second time running in the threat. But if the new MPs will stand crucial divisions on the new Prices and firm, they can act as an inspiration to Incomes Bill. -

NMC); a Public Consultation on Post Registration Standards

Unite the Union (in Health) Professional Team 128 Theobald’s Road, Holborn, London, WC1X 8TN T: 020 7611 2500 | E: [email protected] Unite the Union Response to: The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC); a public consultation on post registration standards. This response is submitted by Unite in Health. Unite is one of the UK’s largest trade union with 1.5 million members across the private and public sectors. The union’s members work in a range of industries including manufacturing, financial services, print, media, construction, transport, local government, education, health and not for profit sectors. Unite represents in excess of 100,000 health sector workers. This includes eight professional associations - British Veterinary Union (BVU), College of Health Care Chaplains (CHCC), Community Practitioners and Health Visitors’ Association (CPHVA), Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists (GHP), Hospital Physicists Association (HPA), Doctors in Unite (formerly MPU), Mental Health Nurses Association (MHNA), Society of Sexual Health Advisors (SSHA). Unite also represents members in occupations such as nursing, allied health professions, healthcare science, applied psychology, counselling and psychotherapy, dental professions, audiology, optometry, building trades, estates, craft and maintenance, administration, ICT, support services and ambulance services. Len McCluskey www.unitetheunion.org General Secretary 2 Executive Summary Introduction Unite CPHVA welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) consultation; a public consultation on post registration standards. Unite CPHVA has been involved in this work from its inception and has had representatives on the Programme Board and Standards Development Group. This has been a positive experience and has been welcomed as Unite CPHVA has been calling for a review of the out dated Specialist Community Public Health Nursing (SCPHN) standards for over ten years. -

Trade Unionism, British Politics and the Media, 1945-1979 by Lucy Bell

From Cooperation to Confrontation? Trade Unionism, British Politics and the Media, 1945-1979 By Lucy Bell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of History February 2018 Some images have been redacted from this electronic copy due to copyright restrictions Acknowledgements Many thanks to Professor Adrian Bingham, who has guided this project with supreme patience and professionalism. He has answered all manner of vague emails and tangential questions with honesty and his feedback has always been thorough and clear. Thanks also to my secondary supervisor, Dr Sarah Miller-Davenport, for providing her thoughts and reflections during the final phases of writing. I am indebted to the number of friends and colleagues at the University of Sheffield who have provided me with ideas and suggestions. Thanks to my parents, Judith and Stuart, for their constant support and my brother Matt, particularly for his comprehensive knowledge of word processing tricks. The treasured friendship of Alex, Fiona and Lizzy has provided much needed laughter and encouragement. Most of all, thanks to my husband Tom, without whom I would not have started this project, let alone finished it. He has supplied me with love, conversation and coffee – three ingredients which were absolutely essential during the grey winter months of writing up. This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/L503848/1) through the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities. For my grandparents 2 Abstract Despite the media’s significant influence on British society’s transformation between 1945 and 1979, relatively little is understood about their effect on the mythologised decline of trade unionism.