Case Study of Fresno, California a C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Resource Guide

SENIOR RESOURCE GUIDE Non-Profit and Public Agencies Serving NORTH ALAMEDA COUNTY Alameda ● Albany ● Berkeley ● Emeryville ● Oakland ● Piedmont Senior Information & Assistance Program – Alameda County Area Agency on Aging 6955 Foothill Blvd, Suite 143 (1st Floor), Oakland, CA 94605; 1-800-510-2020 / 510-577-3530; http://seniorinfo.acgov.org Office Hours : 8:30am – 4pm Monday – Friday ADULT DAY CARE/RESPITE (useful website: www.daybreakcenters.org): Alzheimer's Services of the East Bay - ASEB, Berkeley, www.aseb.org .................................................................................................................................... 510-644-8292 Bay Area Community Services - BACS, Oakland, http://bayareacs.org ................................................................................................................................... 510-601-1074 Centers for Elders Independence - CEI, (PACE - Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly); www.cei.elders.org ..................................................... 844-319-1150 DayBreak Adult Care Centers, (personalized referrals & community education); http://daybreakcenters.org ................................................................ 510-834-8314 Hong Fook Adult Day Health Care, Oakland, (14th Street site); www.fambridges.org ........................................................................................................ 510-839-9673 Hong Fook Adult Day Health Care, Oakland, (Harrison Street site); www.fambridges.org ................................................................................................ -

Senior Resource Guide for Central County

Senior Resource Guide for Central County Nonprofit and Public Agencies Serving Castro Valley ● Hayward ● San Leandro ● San Lorenzo Alameda County Area Agency on Aging 6955 Foothill Boulevard, 3 rd Floor, Oakland CA 94605, 1-800-510-2020 / 510-577-3530 http://alamedasocialservices.org (Revised 10/2010) ADULT DAY CARE/RESPITE (useful web site: www.adsnac.org ) Adult Day Services Network of Alameda County (personalized referrals & community education) ... 510-883-0874 Alzheimer’s Services of the East Bay Adult Day Health Care, Hayward.............................. 510-888-1411 Bay Area Community Services Adult Day Care (serves Hayward) , Fremont............................ 510-656-7742 Center for Elders Independence (PACE—A Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly) . 510-433-1150 LifeLong Medical Care Adult Day Health Care, East Oakland............................................. 510-563-4390 St. Peter’s Community Adult Day Care, San Leandro ......................................................... 510-562-4037 ALCOHOLISM & DRUG ABUSE PREVENTION PROGRAMS Alameda County Health Care ACCESS (referrals to substance abuse services in Alameda County) .. 1-800-491-9099 Alcoholics Anonymous Central Office, Oakland .................................................................. 510-839-8900 CommPre, a program of Horizon Services, Inc. (Prevention strategies to reduce alcohol and medication misuse among older adults) .......................... 510-885-8743 ALZHEIMER’S SERVICES Alzheimer’s Association Helpline ....................................................................................... -

Fresno-Commission-Fo

“If you are working on a problem you can solve in your lifetime, you’re thinking too small.” Wes Jackson I have been blessed to spend time with some of our nation’s most prominent civil rights leaders— truly extraordinary people. When I listen to them tell their stories about how hard they fought to combat the issues of their day, how long it took them, and the fact that they never stopped fighting, it grounds me. Those extraordinary people worked at what they knew they would never finish in their lifetimes. I have come to understand that the historical arc of this country always bends toward progress. It doesn’t come without a fight, and it doesn’t come in a single lifetime. It is the job of each generation of leaders to run the race with truth, honor, and integrity, then hand the baton to the next generation to continue the fight. That is what our foremothers and forefathers did. It is what we must do, for we are at that moment in history yet again. We have been passed the baton, and our job is to stretch this work as far as we can and run as hard as we can, to then hand it off to the next generation because we can see their outstretched hands. This project has been deeply emotional for me. It brought me back to my youthful days in Los Angeles when I would be constantly harassed, handcuffed, searched at gunpoint - all illegal, but I don’t know that then. I can still feel the terror I felt every time I saw a police cruiser. -

Director of Marketing and Communications at Visit Stockton Stockton, California (Northern California/Central Valley)

Director of Marketing and Communications at Visit Stockton Stockton, California (Northern California/Central Valley) Visit Stockton.org [email protected] About Stockton, CA: Stockton is the county seat for San Joaquin County. The City of Stockton continues to be one of California’s fastest growing communities. Stockton is currently the 13th largest city in California with a dynamic, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural population of about 310,000. It is situated along the San Joaquin Delta waterway which connects to the San Francisco Bay and the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. Stockton is located 60 miles east of the San Francisco Bay Area, 83 miles east of San Francisco, and 45 miles south of Sacramento, the capital of California. Stockton has an airport offering service to Phoenix and Las Vegas (on Allegiant Airlines). Visitors may also fly into Sacramento, Oakland or San Francisco. In the mid-2000’s Stockton underwent a tremendous economic expansion and continues to aggressively revitalize its downtown. Projects in the downtown area along the waterfront include an indoor arena, baseball stadium and waterfront hotel. The Bob Hope (Fox) California Theatre, listed on the National List of Historic hosts live performances regularly. The arena is home to the Stockton Kings (NBA G-League) basketball team, the Stockton Heat (AHL) Hockey team, as well as year-round family and cultural events and concerts. Adjacent to the Stockton Arena is the Stockton Ballpark, home of the Stockton Ports Single A Baseball Team (Oakland A’s affiliate). Stockton offers an excellent quality of life for its residents. The City has a number of beautiful residential communities along waterways, with single-family homes costing about one-third the price of homes in the Bay Area. -

2019 Northern California Kaiser Foundation Health Plan Provider

2. Key Contacts 2.1 Northern California Region Key Contacts Department Area of Interest Contact Information KP MSCC Membership Information (888) 576-6789 (Member cost General enrollment questions share and eligibility verification) Eligibility and benefit verification Weekdays : 8a-5p Pacific Co-pay, deductible and co-insurance information Members presenting without KP identification IVR System available number 24 hours / 7 days a week Verifying Member’s PCP assignment Member grievance and appeals Payment status on submitted claims Medical Services Contracting Contract Network Development and Provider (844) 343-9370 Network Management (510) 987-4138 (fax) • Updates to Provider demographics, such as Tax ID, address, and ownership changes P.O. Box 23380 • Practitioner additions/terminations to/from Oakland, CA 94623-2338 your group • Provider education and training • Contract interpretation • Form requests Quality & Operations Support Practitioner Credentialing (510) 625-5608 Medical Services Contracting Facility/Organizational Provider Credentialing (844) 343-9370 Medical Staff Office Kaiser Foundation Hospital Privileges Facility Listing – Section 2.4 Outside Medical Services Authorizations, Referrals by Service • Authorizations, referrals & billing questions for referred services Referral Coordinators - • Coordination of Benefits Facility Listing - Section 2.4 • Third Party Liability • Workers’ Compensation National Claims Emergency Medical Claims (non-Medicare) (800) 390-3510 Administration Billing questions for emergency (non-referred) -

Mid-Century Modernism Historic Context

mid-century Modernism Historic Context September 2008 Prepared for the City of Fresno Planning & Development Department 2600 Fresno Street Fresno, CA 93721 Prepared by Planning Resource Associates, Inc. 1416 N. Broadway Fresno, CA 93721 City of Fresno mid-century Modernism Historic Context mid-century Modernism, Fresno Historical Context Prepared For City of Fresno, Planning and Development Department Prepared By Planning Resource Associates, Inc. 1416 N. Broadway Fresno CA, 93721 Project Team Planning Resource Associates, Inc. 1416 Broadway Street Fresno, CA 93721 Lauren MacDonald, Architectural Historian Lauren MacDonald meets the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualifications in Architectural History and History Acknowledgements Research efforts were aided by contributions of the following individuals and organizations: City of Fresno Planning and Development Department Karana Hattersley-Drayton, Historic Preservation Project Manager Fresno County Public Library, California History and Genealogy Room William Secrest, Librarian Fresno Historical Society Maria Ortiz, Archivist / Librarian Jill Moffat, Executive Director John Edward Powell Eldon Daitweiler, Fresno Modern American Institute of Architects, San Joaquin Chapter William Stevens, AIA Les Traeger, AIA Bob Dyer, AIA Robin Gay McCline, AIA Jim Oakes, AIA Martin Temple, AIA Edwin S. Darden, FAIA William Patnaude, AIA Hal Tokmakian Steve Weil 1 City of Fresno mid-century Modernism Historic Context TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 -

SANTA CLARA Kaiser Foundation Hospital – Northern California Region

SANTA CLARA Kaiser Foundation Hospital – Northern California Region 2019 COMMUNITY BENEFIT YEAR-END REPORT AND 2017-2019 COMMUNITY BENEFIT PLAN Submitted to the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development in compliance with Senate Bill 697, California Health and Safety Code Section 127350. 2019 Community Benefit Year-End Report Kaiser Foundation Hospital-Santa Clara Northern California Region Kaiser Foundation Hospital (KFH)-Santa Clara Table of Contents I. Introduction and Background A. About Kaiser Permanente B. About Kaiser Permanente Community Health C. Purpose of the Report II. Overview of Community Benefit Programs Provided A. California Kaiser Foundation Hospitals Community Benefit Financial Contribution – Tables A and B B. Medical Care Services for Vulnerable Populations C. Other Benefits for Vulnerable Populations D. Benefits for the Broader Community E. Health Research, Education, and Training Programs III. KFH-Santa Clara Community Served A. Kaiser Permanente’s Definition of Community Served B. Map and Description of Community Served C. Demographic Profile of Community Served IV. KFH-Santa Clara Community Health Needs Addressed in 2017-2019 A. Health Needs Addressed and Strategies to Address Those Needs B. Health Needs Not Addressed and Rationale V. 2019 Year-End Results for KFH-Santa Clara C. 2019 Community Benefit Programs Financial Resources Provided by KFH-Santa Clara – Table C D. 2019 Examples of KFH-Santa Clara Grants and Programs Addressing Selected Health Needs VI. Community Health Needs KFH-Santa Clara Will Address In 2020-2022 1 2019 Community Benefit Year-End Report Kaiser Foundation Hospital-Santa Clara Northern California Region I. Introduction and Background A. About Kaiser Permanente Founded in 1942 to serve employees of Kaiser Industries and opened to the public in 1945, Kaiser Permanente is recognized as one of America’s leading health care providers and nonprofit health plans. -

Twirling Bulldogs

FRESNO STATE COLLEGIAN.CSUFRESNO.EDU SERVING CAMPUS SINCE 1922 FRIDAY ISSUE | NOVEMBER 1, 2013 Fresno State helps develop community plan By Erica Heinisch Ashley Swearengin’s priority proj- The city, she said, hired consul- Jane Addams, Southwest, Lowell, pedestrian shed. So in a five to 10 The Collegian ects, particularly Downtown revi- tant group Moule & Polyzoides to Jefferson, Southeast, South Van minute walk from your residence, talization. help canvas neighborhoods and Ness industrial and Downtown. you should be able to have access Fresno State students and fac- Quan said the community plan create policies. The city aims to make neigh- to transit, a school, a park or open ulty are taking part in advanc- is a broader policy document than “The plan is 7,200 acres of borhoods more pedestrian friend- space and a grocery store.” ing the development of Fresno’s the Fulton Corridor Specific Plan, Fresno’s urban core, which ly and active to create a stronger Together, the city and consul- Downtown Neighborhood a detailed plan involving Fulton includes the Downtown triangle,” sense of community, Quan said. tant group conducted community Community Plan, which is expect- Mall that will return two-way Quan said. “The goal of the plan is to outreach in each neighborhood to ed to be adopted in 2014. through traffic to the mall. Together, the city and Moule & make sure that people have easy get feedback about the wants and Fresno urban planning special- The community plan has been Polyzoides divided that area into access,” Quan said. “We talk ist Wilma Quan manages Mayor under way since 2010, Quan said. -

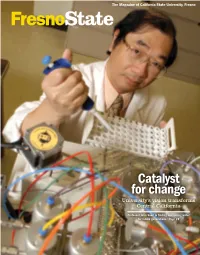

Catalyst for Change University’S Vision Transforms Central California

The Magazine of California State University, Fresno Catalyst for change University’s vision transforms Central California Professor John Suen is finding and saving water for future generations. Page 28 FresnoState Magazine is published twice annually by the Office of University Communications at California State University, Fresno. Spring 2007 President John D. Welty Vice President of University Advancement Peter N. Smits Associate Vice President for University Communications Mark Aydelotte Director of News Services/Magazine Editorial Direction Shirley Melikian Armbruster FresnoState Magazine Editor Lanny Larson Director of Publications and New Media Bruce Whitworth Graphic Design Consultant Pam Chastain Alumni Editor Sarah Woodward campus notes 4 University Communications Editorial Team Margarita Adona, Esther Gonzalez, Todd Graves, The buzz is about bees and building, crime-solving and Priscilla Helling, Angel Langridge, Kevin Medeiros, culture, teaching and time. April Schulthies, Tom Uribes Student Assistants Megan Jacobsen, Brianna Simpson, Andrea Vega campus news 6 Global connections to education, exercise, water The opinions expressed in this magazine do not necessarily reflect official university policy. Letters to the editor and contributions to development and conservation and enhanced the Class Notes section are welcome; they may be edited for clarity farmland use share the spotlight with campus initiatives and length. Unless otherwise noted, articles may be reprinted as on athletics finances and cultural heritage. long as credit is given. Copyrighted photos may not be reprinted without express written consent of the photographer. Clippings and other editorial contributions are appreciated. All inquiries and comments, including requests for faculty contact information, giving news 10 21 should be sent to Editor, FresnoState Magazine, 5241 N. -

BOARD of EDUCATION REGULAR MEETING Fresno Unified School District

BOARD OF EDUCATION REGULAR MEETING 2309 TULARE STREET BOARD ROOM, SECOND FLOOR FRESNO, CA 93721-2287 www.fresnounified.org/board MINUTES - BOARD OF EDUCATION REGULAR MEETING Fresno Unified School District Fresno, California October 21, 2020 In accordance with Executive Order N-29-20 Paragraph 3, the October 21, 2020 Board of Education meeting was held via teleconferencing and was available for all members of the public seeking to observe via 31T31T UUhttp://go.fresnounified.org/ustream/ UU31T31T, or on the Ustream App on your 31T 31TAndroid31T 31T or 31T31TApple31T31T device, Comcast Xfinity Channel 94 and AT&T U-Verse Channel 99, or through the following teleconference line: Teleconference Line – English: Dial in: +1 559-512-2623, Passcode: 982 851 552#; Teleconference Line – Spanish: Dial in: +1 559-512-2623, Passcode: 951 997 541#. At a Regular Meeting of the Board of Education of Fresno Unified School District, held on October 21, 2020, there were present Board Members Davis, Cazares, Islas, Jonasson Rosas, Mills, Major Slatic, and President Thomas. Superintendent Nelson was also present. Board President Thomas CONVENED the Regular Board Meeting at 4:30 p.m. and ADJOURNED to Closed Session to address items one through seven. The Board RECONVENED in Open Session at 6:02 p.m. Reporting Out of Closed Session • On a motion by Board Member Islas, seconded by Board Member Mills, by a roll call vote of 7-0-0-0, the Board took action in closed session to promote Amanda Harvey as Director of Food Services. HEAR Reports from Student Board Representatives The Board heard a report from Jocelyn Goytortua and Emmanuel Enriquez Ocana Student Advisory Board representatives from McLane High School, and students from Scandinavian Middle School. -

Ashley Swearengin 6

“[Swearengin] is viewed by political handicappers as an up-and-coming contender and her regional bent is giving her a higher profile.” CAPITOL WEEKLY, August 8, 2011 www.AshleyForCalifornia.com Dear Friend, The State Controller has been called the second most influential position in state government. That’s because the State Controller has tremendous influence over California’s tax and economic growth policies. In the City of Fresno, we understand just how important it is for our State to improve its business climate and encourage job growth. We’ve made City Hall more business friendly. We’ve created new venues to market our products. We’ve worked to attract jobs and help those here expand their operations. But, we need Sacramento to focus on making California more attractive to job creators. As State Controller, I can help our state take major steps toward a pro-job-growth tax policy. I look forward to meeting with you in the coming weeks as we work together to improve our State. Proven, Effective Leadership for Californiav 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Reaction to Mayor Swearengin’s Candidacy 2 Office of Controller 3 Fresno Success - Mastering the Challenges 4 Named “One of the Best Mayors” 5 Biography - Ashley Swearengin 6 Contact the Campaign 7 Proven, Effective Leadership for California v 3 Executive Summary v Fresno Mayor Ashley Swearengin is considered a rising star in California and national political circles. v Fresno is California’s 5th largest city and the agribusiness capital of the world. Mayor Swearengin has been lauded nationally for her success at reforming Fresno’s $1 billion annual budget, while remaking City Hall and helping grow the local jobs base. -

FINAL OAK-SFO Noise Proposals-3-13-17

OAKLAND AIRPORT-COMMUNITY NOISE MANAGEMENT FORUM An Advisory Body to the Executive Director of the Port of Oakland March 24, 2017 Co-Chairs Benny Lee, Mr. Dennis Roberts, Regional Administrator Elected- Federal Aviation Administration representative Western-Pacific Region City of San Leandro P.O. Box 92007 Walt Jacobs, Los Angeles, CA 90009 Citizen- representative RE: Recommendations to Adjust/Revise Metroplex Procedures Affecting East City of Alameda Bay Communities Members Dear Administrator Roberts: City of Alameda Long standing issues with, and changes to the San Francisco Bay Area airspace as a City of Berkeley result of implementation of the Northern California Metroplex in November 2014 have City of Hayward resulted in significant increases in noise complaints from affected communities in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, primarily Alameda and Contra Costa City of Oakland Counties. The Oakland Airport-Community Noise Management Forum (Forum) serves as an advisory body on community noise concerns to the Executive Director of the Port City of San Leandro of Oakland and includes one elected official and one community member each from six City of Union City neighboring cities, as well as Alameda County. The Forum represents a combined regional population of almost 2 million people. County of Alameda Community issues and concerns over the implementation of certain NextGen air traffic Port of Oakland management procedures were brought to the attention of your immediate predecessor, Forum Facilitator former FAA Regional Administrator Mr. Glen A. Martin. In response to consultations with, and at the behest of Mr. Martin, the Forum accepted the role as the link to the Michael R.