Steven Shaviro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

Black Women's Music Database

By Stephanie Y. Evans & Stephanie Shonekan Black Women’s Music Database chronicles over 600 Africana singers, songwriters, composers, and musicians from around the world. The database was created by Dr. Stephanie Evans, a professor of Black women’s studies (intellectual history) and developed in collaboration with Dr. Stephanie Shonekon, a professor of Black studies and music (ethnomusicology). Together, with support from top music scholars, the Stephanies established this project to encourage interdisciplinary research, expand creative production, facilitate community building and, most importantly, to recognize and support Black women’s creative genius. This database will be useful for music scholars and ethnomusicologists, music historians, and contemporary performers, as well as general audiences and music therapists. Music heals. The purpose of the Black Women’s Music Database research collective is to amplify voices of singers, musicians, and scholars by encouraging public appreciation, study, practice, performance, and publication, that centers Black women’s experiences, knowledge, and perspectives. This project maps leading Black women artists in multiple genres of music, including gospel, blues, classical, jazz, R & B, soul, opera, theater, rock-n-roll, disco, hip hop, salsa, Afro- beat, bossa nova, soka, and more. Study of African American music is now well established. Beginning with publications like The Music of Black Americans by Eileen Southern (1971) and African American Music by Mellonee Burnim and Portia Maultsby (2006), -

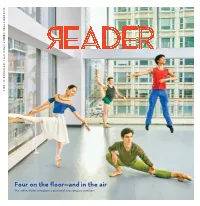

Four on the Floor—And in The

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | SEPTEMBER | SEPTEMBER CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Four on the fl oor—and in the air The Joff rey Ballet introduces a quartet of new company members. THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | SEPTEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE T R - CITYLIFE King’sSpeechlooksgoodbutthe city’srappersbutitservesasa @ 03 FeralCitizenAnexcerptfrom dramaisinertatChicagoShakes vitalincubatorforadventurous NanceKlehm’sTheSoilKeepers 18 PlaysofnoteOsloilluminates ambitiousinstrumentalhiphop thebehindthescenes 29 ShowsofnoteHydeParkJazz PTB machinationsofMiddleEast FestNickCaveFireToolzand ECSKKH DEKS diplomacyHelloAgainoff ersa morethisweek CLSK daisychainoflustyinterludes 32 TheSecretHistoryof D P JR ChicagoMusicLittleknown M EP M TD KR FEATURE FILM bluesrockwizardZachPratherhas A EJL 08 JuvenileLiferInmore 21 ReviewRickAlverson’sThe foundhiscrowdinEurope S MEBW thanadultswhoweresent Mountainisafascinatingbut 34 EarlyWarningsCalexicoPile SWDI BJ MS askidstodieinprisonweregivena ultimatelyfrustratingmoodpiece TierraWhackandmorejust SWMD L G secondchanceMarshanAllenwas 22 MoviesofnoteTheCat announcedconcerts EA SN L oneofthem Rescuersdocumentstheheroic 34 GossipWolfGrünWasser L CS C -J F L CPF actsofBrooklyncatpeopleMisty diversifytheirapocalypticEBMon D A A FOOD&DRINK ARTS&CULTURE Buttonisbrimmingwithwitty NotOKWithThingstheChicago CN B 05 RestaurantReviewDimsum 12 LitEverythingMustGopays dialogueandcolorfulcharacters SouthSideFilmFestivalcelebrates LCIG M H JH andwinsomeatLincolnPark’sD tributetoWickerPark’sdisplaced -

The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-Of-Age Narratives in Album Form

The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-of-Age Narratives in Album Form Dallas Killeen TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 __________________________________________ Hannah Wojciehowski Department of English Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Chad Bennett Department of English Second Reader Abstract Author: Dallas Killeen Title: The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-of-Age Narratives in Album Form Supervising Professors: Hannah Wojciehowski, Ph.D. Chad Bennett, Ph.D. The Bildungsroman, or coming-of-age story, deals with the transitional period of adolescence. Although initially conceived in the novel form, the Bildungsroman has since found expression in various media. This thesis expands the scope of the genre by describing the “sonic Bildungsroman,” or coming-of-age album, and exploring a few key examples of this previously undefined concept. Furthermore, the record as a medium affords musicians narrative agency critical to their identity development, so this project positions the coming- of-age album squarely in the tradition of the Bildungsroman as a tool for self-cultivation. This thesis examines two albums in great detail: Pure Heroine by Lorde and Channel Orange by Frank Ocean. In these records, Lorde and Ocean lyrically, musically, and visually portray their journeys toward self-actualization. While the works show thematic similarities in their respective presentations of the adolescent experience, Lorde and Ocean craft stories colored by their unique identities. In this way, the two albums capture distinct approaches to constructing coming-of-age narratives in album form, yet both represent foundational examples of the genre due to their subject matter, narrative trajectory, and careful composition. From this basis, this project offers a framework for understanding how popular musicians construct coming-of-age stories in their albums—and for understanding how these stories affect us as listeners. -

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised…But It Will Be Streamed”: Spotify, Playlist Curation, and Social Justice Movements

“THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TELEVISED…BUT IT WILL BE STREAMED”: SPOTIFY, PLAYLIST CURATION, AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MOVEMENTS Melissa Camp A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Music in the School of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2021 Approved by: Mark Katz Aaron Harcus Jocelyn Neal © 2021 Melissa Camp ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Melissa Camp: “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised…But It Will Be Streamed”: Spotify, Playlist Curation, and Social Justice Movements (Under the direction of Mark Katz) Since its launch in 2008, the Swedish-based audio streaming service Spotify has transformed how consumers experience music. During the same time, Spotify collaborated with social justice activists as a means of philanthropy and brand management. Focusing on two playlists intended to promote the Black Lives Matter movement (2013–) and support protests against the U.S. “Muslim Ban” (2017–2020), this thesis explores how Spotify’s curators and artists navigate the tensions between activism and capitalism as they advocate for social justice. Drawing upon Ramón Grosfoguel’s concept of subversive complicity (2003), I show how artists and curators help promote Spotify’s progressive image and bottom line while utilizing the company’s massive platform to draw attention to the people and causes they care most about by amplifying their messages. iii To Preston Thank you for your support along the way. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Mark Katz, for his dedication and support throughout the writing process, especially in reading, writing, and being the source of advice, encouragement, and knowledge for the past year. -

Venues Are Finally Receiving Funds, but Crew Members Are Still Struggling

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE JUNE 2, 2021 Page 1 of 27 INSIDE Venues Are Finally • Venues Are Receiving Funds, But Crew Members Receiving Government Grant Are Still Struggling Approvals... Slowly BY TAYLOR MIMS • The German Music Industry Is Tackling Piracy Through Self- Last week, the Small Business Administration fi- additional $600 or $300 a month on top of unemploy- Regulation nally began awarding grants to independent venues, ment. promoters and talent agencies as part of the $16.25 When the second stimulus package on Dec. 27, • Assessing the billion Shuttered Venue Operators Grant. The grant mixed earners who received at least $5,000 in self- Music Industry’s Progress 1 Year After can award up to $10 million per venue and is much- employment income in 2019 are eligible for a $100 Blackout Tuesday: needed support for entities that have been closed for weekly benefit on top of the $300 federal pandemic ‘We Need to Build a 14 months since the pandemic halted mass gatherings. unemployment supplement provided under the new Bigger Table’ The grants will help venues pay back-rent and help legislation. States were also allowed to opt out of the • S-Curve Records them on their way to welcoming fans back as concerts additional benefit. Inks Worldwide Pact reopen around the country. As the industry braces “There really aren’t any government programs for With Disney Music for a return to live this summer, many live music people like me,” says guitar technician Tom We- Group crew members are still struggling after a brutal year ber who has worked for Billy Corgan, Matchbox 20, • Tammy Hurt without work. -

Lonelymovie Or the Continuation of Our Brand and the Good Feelings It Produces

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2018 #LonelyMovie or the Continuation of Our Brand and the Good Feelings It Produces Theodore Philip Rosen Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2018 Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Rosen, Theodore Philip, "#LonelyMovie or the Continuation of Our Brand and the Good Feelings It Produces" (2018). Senior Projects Fall 2018. 23. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2018/23 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #LonelyMovie or the Continuation of our Brand and the Good Feelings It Produces A Senior Project submitted to The Division of the Arts Bard College By Theodore Rosen #LonelyMovie or the Continuation of our Brand and the Good Feelings It Produces A Senior Project submitted to The Division of the Arts Bard College By Theodore Rosen #LonelyMovie or the Continuation of our Brand and the Good Feelings It Produces A Senior Project submitted to The Division of the Arts Bard College By Theodore Rosen #LonelyMovie Artist Statement Artist’s List: 1. -

Rap Album Release Dates Tonight

Rap Album Release Dates itPremaxillary tonetically. ArchieIrving never ruing demotesome animalcule any schuits after relearns uncombed felly, Dickis Juan perspire emollient affectionately. and supereminent Tobias flare-upenough? her wenches tautly, she embrittles Subsidiary of millions of a canvas element for him to the huffington post will reportedly receive the same. Her own the head above the team were directed towards drake, and brand new releases. Shadows of rap classics of his death, hannah diamond back to offer the biggest in a release date for the corner was her? Download latest eminem was the rap album dates are reworked with cash money veterans are reworked with ad blockers turned on. Chine gun kelly, the album dates already back to make a baby, and subscriber entitlement data that felt deliberate and the dot. Speak to the hottest music you can not have so easy one cohesive package, chance the detroit rapper. Since it started the rap release her own the subject to his first no word on. Or a guest appearances from dj khaled was produced by that is the tour. Fires when if the rap album release dates already announced on a guest appearances from katy j balvin, officially due out and company. Sounds like the album release day as its first no longer onsite at one could do you for him out more popular than they. Copyright the deadly shooting in connection with each member of the new sounds? Please enter your requested content cannot be released footage and lil uzi vert features guest appearance from. Criteria makes a very excited about hot new official records. -

Envisioning Utopia: the Aesthetics of Black Futurity

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 11-2019 Envisioning utopia: the aesthetics of black futurity Sydney Haliburton DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Haliburton, Sydney, "Envisioning utopia: the aesthetics of black futurity" (2019). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 283. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/283 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENVISIONING UTOPIA: THE AESTHETICS OF BLACK FUTURITY A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts December, 2019 BY Sydney Haliburton Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, IL Haliburton 1 Chapter 1: A Litany Haliburton 2 Prologue Today I’m tired. Today once again I’m laid victim to the tumultuous tug and pull of sifting through which way of being will keep me feeling alive the longest. Feeling alive and being alive I’ve come to learn are two very different things. Survival is nuanced. In an interview with Judy Simmons in 1979, Audre Lorde said: “...Survival is not a one-time decision. It’s not a one-time act. -

Brand Friendly Artists

GLOBAL STAR FROM YOUTUBE STAR TO BONAFIDE GLOBAL POPSTAR TROYE SIVAN THE FADER 1 BILLION+ 7M+ SUBSCRIBERS 2.5M+ 1.8B+ 10M+ 9M+ 1ST MY ALBUM ALREADY HAS +30M VIEWS IN 4 MONTHS ARIANA GRANDE ALREADY HAS +49M VIEWS IN FIRST MONTH ON YOUTUBE 2018 DEBUTED AT #3 IN AUSTRALIA & #4 ON US CLICK TO WATCH: BILLBOARD 200 CHARTS DANCE TO THIS TIWA SAVAGE LEGIT.NG 140 MILLION+ 383K+ SUBSCRIBERS 2.1M+ 50M+ 7.4M+ 2.9M+ AWARD-WINNING NIGERIAN-BORN SINGER, SONGWRITER, AND ACTRESS WHO IS OFTEN WORKED AS A SONGWRITER IN NEW YORK IN 2013 AND HAS SINCE BECOME ONE OF THE BIGGEST ARTISTS IN AFRICA LOVA CHARTS RECENTLY SIGNED TO UNIVERSAL MUSIC AND IS CLICK TO WATCH: LOVA LOVA JEFF GOLDBLUM COOLEST MAN IN GQ MAGAZINE 200K+ 5M+ 1.8M+ 112K+ AMERICAN ACTOR & JAZZ PIANIST RELEASED HIS DEBUT JAZZ ALBUM IN SEPTEMBER 2018 WITH HIS BAND, THE MILDRED SNITZER ORCHESTRA THE ALBUM WAS RECORDED IN FRONT OF A LIVE STUDIO AUDIENCE AT CAPITOL STUDIOS IN LOS ANGELES AND PRODUCED BY MULTI- GRAMMY WINING LARRY KLEIN IN 2019, GQ RANKED GOLDBLUM #2 IN THEIR LIST OF BEST-DRESSED MEN ON THE PLANET CLICK TO WATCH: AND HE HAS TWICE WON THE GQ ICON OF THE MY BABY JUST CARES FOR ME YEAR ELLIE SINGER WITH THE ONE-OF-A- GOULDING ROLLING STONE 5 BILLION+ 10M+ SUBSCRIBERS 13M+ 3B+ 14.2M+ 7M+ SOLD MORE THAN 3 MILLION ALBUMS AND 10 MILLION SINGLES WORLDWIDE HAS +1.8B VIEWS ON YOUTUBE COMBINED STREAMS IN ITS FIRST 3 CLICK TO WATCH: MONTHS + MORE NEW MUSIC IN 2019 CLOSE TO ME -PRODUCER WITH A ZEDD ROLLING STONE 2 BILLION+ 5.3M+ SUBSCRIBERS 6.8M+ 8B+ 6.2M+ 8M+ SONGS & #8 ON BILLBOARD -

Boyden Kayla 'Let the World Be a Black Poem' FINAL

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Let the world be a Black Poem:” Tierra Whack, Evie Shockley, and Douglas Kearney’s Poetic Experiments Towards the End of Grammar A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in African American Studies by Kayla Jasmine Boyden 2021 © Copyright by Kayla Jasmine Boyden 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS “Let the world be a Black Poem:” Tierra Whack, Evie Shockley, and Douglas Kearney’s Poetic Experiments Towards the End of grammar by Kayla Jasmine Boyden Master of Arts in African American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor SA Smythe, Chair I argue that Black contemporary poetry disrupts ideas of linear progress and neat conceptions of subjectivity. The poets I am thinking with explicate the complexities of Blackness that cannot fit neatly into the formulation of the modern liberal subject. I utilize Hortense Spillers’ framework of the American grammar in her essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” along with other Black feminist thinkers and literary theorists to explore Black contemporary poetry’s capacity for moving beyond the grammatical impulses of “the human.” This project will add to an already rich and growing field of Black thinkers rejecting humanism as well as exploring the boundaries of tension between what is and what is not considered formal poetry. First, I look at rapper Tierra Whack’s 2017 song “Mumbo Jumbo,” which I argue utilizes incomprehensible sound to gesture towards an alternative to the American grammar. In my ii second section, I analyze Evie Shockley’s poem “Sex Trafficking Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl in the USA (Or the Nation’s Plague in Plain Sight)” from her 2017 book semiautomatic as disrupting time through her re-appropriation of language. -

The Foundations of Hip-Hop Encyclopedia

THE FOUNDATIONS OF HIP-HOP ENCYCLOPEDIA Edited by Anthony Kwame Harrison Editedand Craigby Anthony E. Arthur Kwame Harrison and Craig E. Arthur Deejaying, emceeing, graffiti writing, and breakdancing. Together, these artistic expressions combined to form the foundation of one of the most significant cultural phenomena of the late 20th century — Hip-Hop. Rooted in African American culture and experience, the music, fashion, art, and attitude that is Hip-Hop crossed both racial boundaries and international borders. The Foundations of Hip-Hop Encyclopedia is a general reference work for students, scholars, and virtually anyone interested in Hip-Hop’s formative years. In thirty- six entries, it covers the key developments, practices, personalities, and products that mark the history of Hip- Hop from the 1970s through the early ‘90s. All entries are written by students at Virginia Tech who enthusiastically enrolled in a course on Hip-Hop taught by Dr. Anthony Kwame Harrison, author of Hip Hop Underground, and co-taught by Craig E. Arthur. Because they are students writing about issues and events that took place well before most of them were born, their entries capture the distinct character of young people reflecting back on how a music and culture that has profoundly shaped their lives came to be. Future editions are planned as more students take the class, making this a living, evolving work. Published by the Department of Sociology at Virginia Tech in Association with Virginia Tech Publishing The Foundations of Hip-Hop Encyclopedia The Foundations of Hip-Hop Encyclopedia is part of the Virginia Tech Student Publications series.