8 LIGHTING CONTROLS 8.1 Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Switches and Relays for the Power Industry

Switches and Relays For the Power Industry E L E C T R O NEVER S W I T A DOUBT C H U T I L I T Y ELECTROSWITCH Corporation 180 King Avenue P Weymouth, MA 02188 R TEL: (781) 335-5200 O FAX: (781) 335-4253 www.electroswitch.com D U C T S 5M 113 Printed in USA U.2.D THE ELECTRO SWITCH CORPORATion Family… PROVIDING INTELLIGENT SOLUTIONS FOR SWITCHING AND CONTROL Complete line of electrically and manually activated Rotary Switches and Relays POWER SWITCHES & RELAYS for electric utility, defense, and industrial monitoring and control applications The Best Rotary Switches, Relays, and Electrical Systems Products... Backed by the industry’s most www.electroswitch.com knowledgeable and responsive Rotary Switches; Miniature Toggle, Paddle, Rocker, Power Toggle, and Push- ELECTRONIC PRODUCTS Button Switches; Hall Effect, and Mechanical Encoders; Illuminated Switch engineering and customer Products; and Power Transformers service professionals... Any way you want them... Delivered when you need them. www.electro-nc.com DIGITRAN Digital and Rotary Switch Products designed for aviation, defense, and industrial DIGITAL & ROTARY SWITCHES switch applications ELECTROSWITCH www.digitran-switches.com ARGA CONTROLS Electric utility, industrial and military-grade Power Meters, Battery Monitors, MEASUREMENT & CONTROL INSTRUMENTATION and Transducers for precision measurement applications NEVER www.argacontrols.com Sunrise Technologies Wireless Communication Systems for Smart Grid applications and a complete A DOUBT OUTDOOR LIGHTING CONTROLS & MONITORING line -

Product Manual Heat Recovery Ventilation Units EN

EN HMB/HMBE aura-t & auralite® compatible HRV units HRV20 Q Plus ECO TP650HMB HRV20 HE Q Plus ECO TP652HMB B/BC/BE aura compatible HRV units HRV20 Q Plus ECO TP651B HRV20 HE Q Plus ECO TP653B Cold Climate HRV units HRV20 Q Plus ECO* TP651BC HRV20 HE Q Plus ECO* TP653BC *Special Order Only Heat Recovery Ventilation Units Product Manual ventilation systems Warnings, Safety Information and Guidance Important Information Important: read these instructions fully before the installation of this appliance 1. Installation of the appliance and accessories must be carried out by a qualified and suitable competent person and be carried out in clean, dry conditions where dust and humidity are at minimal levels. 2. This manual covers the installation of the Heat Recovery Ventilation (HRV) unit 3. All wiring must conform to current I.E.E. Wiring Regulations and all applicable standards and Building Regulations. 4. Inspect the appliance and electrical supply cord. If the supply cord is damaged, it must be replaced by the manufacturer, their service agent or similarly qualified persons in order to avoid a hazard. 5. The unit is supplied with a mains rated 3 core flexible cord (PVC sheathed, brown, blue and green/yellow 0.75mm²). 6. The appliance must be connected to a local double pole isolation switch with a contact separation of at least 3mm. 7. The appliance must be earthed.. 8. HRV20 Q Plus suitable for 230V ~ 50/60Hz single phase with a fuse rating of 5A. 9. auralite® & aurastat®, control & communication cable access is via the fitted cable gland(s) which are suitable for Ø3- 6mm cable. -

Sirens and Controls

INSTALLATION & OPERATION MANUAL 3990 SERIES SIRENS PATENT PENDING RLS SERIES SIRENS AND CONTROLS Contents: Introduction .....................................................................2 Standard Features ........................................................2 Unpacking & Pre-Installation......................................4 Installation & Mounting ................................................4 Set-Up and Adjustment ...............................................8 Operation...................................................................... 1 0 Maintenance ................................................................ 1 5 Troubleshooting.......................................................... 1 6 Wiring Diagram ........................................................... 1 8 Diagnostic Function................................................... 1 9 Options .......................................................................... 1 9 Specifications.............................................................. 1 9 Parts List ....................................................................... 2 1 Warranty........................................................................ 2 8 Read all instructions and warnings before installing and using. IMPORTANT: INSTALLER This manual must be delivered to the end user of this equipment. Introduction The 3990 series siren is a new series of remote control electronic sirens that has been designed to meet the needs of all emergency vehicles. This series of sirens incorporates the -

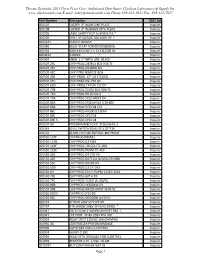

Replacement Parts

Thermo Scientific 2021 Parts Price List - Authorized Distributor Clarkson Laboratory & Supply Inc. www.clarksonlab.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone 619-425-1932 Fax: 619-425-7917 Part Number Description 2021 List 000107 CASTER 3" W/MOUNT PLATE Inquire 000108 CASTER 3" W/BRAKE MTG PLATE Inquire 000205 LABEL SAFETY HOT SURFACE IEC * Inquire 000230 CONT 3P 120VAC 30A 600V DP ! Inquire 0003344 PLASTIC NOZZLE Inquire 000340 RELAY START FOR 007909(SERV)! Inquire 000394 XDUCER FLOW 1.5-12 CELCON HE Inquire 0004142 HANDLE * Inquire 000450 KNOB 1.5" WITH LINE BLACK Inquire 000507.29C CHIP PROG CNTRL3 BUS ROUTE Inquire 000507.35C CHIP PROG HX300W D3 Inquire 000507.42C CHIP PTRG REMOTE BOX Inquire 000507.44E CHIP PROG CFT D2 (TC200) Inquire 000507.45C CHIP PROG HX+750 D3 Inquire 000507.63D CHIP PROG EATON 151 D4 Inquire 000507.73B CHIP PROG TC300 BUS ROUTE Inquire 000507.76A CHIP PROG HX D2 D2+I Inquire 000507.79A CHIP PROG SYS3 AMAT D4 Inquire 000507.83A CHIP PROG STEELHEAD 0 30-80C Inquire 000507.86B CHIP PROG SYS3 D4 CES Inquire 000507.88C CHIP PROG HX300 D3 SEMI Inquire 000507.89E CHIP PROG SYS3 D4 Inquire 000507.89E S CHIP PROG SYS3 D4 Inquire 000507.9H PROGRAMMED CHIP STEELHEAD-1 Inquire 000543 LEVEL SWITCH DUAL SS 1.25"316 Inquire 000550 BLANK CHIP MICROPROC 48K PROM Inquire 000550.107F CHIPPROGDIMAX2 Inquire 000550.115B CHIP PROG D3 SWX Inquire 000550.119F CHIP PROG -30 CDU TC-400 Inquire 000550.125E CHIP PROG PUMA TC-400 Inquire 000550.36S CHIP PROG D4 STD HX Inquire 000550.42E CHIP PROG HX75 D4 NOVELLUS+IBM Inquire 000550.53C CHIP -

Ventilation Systems Catalogue Contents

Ventilation Systems Catalogue Contents Welcome to Titon Ventilation Systems. We are experts in the design, manufacture, specification and supply of residential ventilation systems. Our extensive range and comprehensive support will provide you with a solution for any housing project. About Titon 4 Ventilation Systems 5 Sales & Service 6 Quality & Testing 7 Controls, Switches and Sensors Heat Recovery aura-tTM ..............................................................................58 HRV1.35 Q Plus ...................................................................8 auramode® .........................................................................59 HRV1.35 Q Plus - Enthalpy ................................................10 aurastat® V & VT ..................................................................60 HRV1.6 Q Plus ....................................................................12 auralite® ...............................................................................61 HRV1.75 Q Plus ..................................................................14 Switches ..............................................................................62 HRV2 Q Plus .......................................................................16 Sensors ...............................................................................63 HRV2 Q Plus - Enthalpy .....................................................18 HRV2.85 Q Plus ..................................................................20 Extract Ventilation HRV3 Q Plus .......................................................................22 -

Starter Guide B a S I C W I R E L E S S L I G H T S W I T C H K I T ( E 8 K - a 1 1 - X X ) Wireless Lighting Control AHD0018C

Starter Guide B A S I C W I R E L E S S L I G H T S W I T C H K I T ( E 8 K - A 1 1 - X X ) Wireless Lighting Control AHD0018C I N T R O D U C T I O N Material Typical Range Masonry 65 ft. (20m), through 3 walls max. Self-powered wireless controls make wireless lighting control simple and reliable. The light switches do not Reinforced concrete 32 ft. (10m), through 1 wall / ceiling max. store power or use batteries; instead, the switches Wood walls / drywalls 98 ft. (30m), through 5 walls max. operate using energy from the motion of a switch press. When pressed, a wireless light switch sends radio signals I N S T A L L A T I O N to a receiver telling the receiver to turn lights/devices on or off. CAUTION: The 120V Relay Receiver is to be installed and/or used in compliance with relevant electrical codes Figure 1. Basic Components and regulations. If you are unsure about any portion of these instructions, please contact a qualified electrician. Wiring The 120V Relay Receiver (E8R-R12BP-1) is wired between the light fixture and the power source. Wireless Light Switch à Relay Receiver à Controlled Device 1. WARNING: To avoid fire, shock, or death, TURN OFF B E N E F I T S POWER at circuit breaker or fuse and verify that it is OFF before installation begins. Make sure that it • Add light switches quickly and easily remains OFF until installation is complete. -

Project #6: Building a Shed

Project #6: Building a Shed Lesson #4: Electrical (20 class periods) Objectives Students will be able to… . Understand the progress of using electricity in housing. Develop and apply basic skills in electrical wiring work. Find at least three codes in the NEC that govern electrical construction. Students practice calculating current, resistance, and voltage. Given the power equation, calculate the power consumed in a circuit or load. Name and identify electrical symbols while reading electrical plans . Layout and install a circuit from blueprints. Identify the tools and equipment used by electricians today. Define terms related to electrical safety. Identify electrical wiring tools and materials. Demonstrate safe working procedures in a construction and shop/lab environment. Work cooperatively as a member of a team. Identify electrical hazards and how to avoid or minimize them in the workplace. Common Core Standards LS 11-12.6 RSIT 11-12.2 RLST 11-12.2 Writing 9-10.5 Geometry 4.0 Residential and Commercial Construction pathway D2.8, D3.1, D11.1, D11.2, D11.3, D11.4, D11.9, D11.11 Problem Solving and Critical Thinking 5.2, 5.3, 5.4 Health and Safety 6.2, 6.3, 6.7, 6.10 Responsibility and Leadership 7.3, 7.4, 7.5, 7.6, 7.7, 9.2, 9.3, 9.6, 9.7 Materials © BITA: A program promoted by California Homebuilding Foundation BUILDING INDUSTRY TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY: YEAR TWO CURRICULUM Electrical history terms handout and worksheet History of Wire and Cable Systems Handout History of Wire and Cable Systems Worksheet YouTube Video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SdjyNoWQX5k -

Commercial Systems Technical Guide 230 V (CE) and 220-240 V (Non-CE) Lutron® Commercial Systems Technical Guide

commercial systems technical guide 230 V (CE) and 220-240 V (non-CE) Lutron® Commercial systems technical guide Lutron World Headquarters, Coopersburg, Pennsylvania Innovation and quality from the world leader in lighting controls. In 1961, Lutron introduced the world’s first electronic (solid-state) dimmer. From that point forward, Lutron innovations transformed the world of lighting controls. Today, with more than 75 utility and 180 design patents, and more than 10,000 products shipped to 80 countries worldwide, Lutron continues to lead the way with innovation and quality. seeTouchTM Wallstations from Lutron – the new standard for ease of use and intuitive control. www.lutron.com Lutron® Commercial systems technical guide Lutron’s first principle is to take care of our customer. Worldwide sales and service Commitment to innovation Lutron has been dedicated to producing innovative lighting controls for The Lutron Team is here to support homes of every type and style since 1961. A dedication matched only by our youwhenever you need us. commitment to quality, performance, value, and service for our customers. Customer service World-class quality and technical support: Lutron quality is fueled by a relentless pursuit of the highest standards. Asia +852-2104-7733 Constant improvement activities include an integrated quality system, strict France 0800-90-12-18 engineering guidelines, and world-class quality and manufacturing processes. Germany 00800-5887-6635 Spain 0900-948-944 Comprehensive lighting control solutions United Kingdom 0800-282-107 for electric and natural light For the rest of Europe Lutron is your comprehensive resource for lighting control solutions Customer service +44-207-702-0657 for any commercial or institutional application. -

Product Manual Heat Recovery Ventilation Units EN

EN H200 H300 H200 Q Plus ECO 204x60 TP451HMB H300 Q Plus ECO 204x60 TPxxxHMB H200 Q Plus ECO Ø150 TP452HMB H300 Q Plus ECO Ø150 TPxxxHMB H200 Q Plus ECO Ø160 TP453HMB H300 Q Plus ECO Ø160 TPxxxHMB H200 Q Plus ECO aurastat® 204x60 TP461B H300 Q Plus ECO aurastat® 204x60 TPxxxB H200 Q Plus ECO aurastat® Ø150 TP462B H300 Q Plus ECO aurastat® Ø150 TPxxxB H200 Q Plus ECO aurastat® Ø160 TP463B H300 Q Plus ECO aurastat® Ø160 TPxxxB Product Manual Heat Recovery Ventilation Units ventilation systems Warnings, Safety Information and Guidance Important Information Important: read these instructions fully before the installation of this appliance 1. Installation of the appliance and accessories must be carried out by a qualified and suitable competent person and be carried out in clean, dry conditions where dust and humidity are at minimal levels. 2. This manual covers the installation of the Heat Recovery Ventilation (HRV) unit 3. All wiring must conform to current I.E.E. Wiring Regulations and all applicable standards and Building Regulations. 4. Inspect the appliance and electrical supply cord. If the supply cord is damaged, it must be replaced by the manufacturer, their service agent or similarly qualified persons in order to avoid a hazard. 5. The unit is supplied with a mains rated 3 core flexible cord (PVC sheathed, brown, blue and green/yellow 0.75mm²). 6. The appliance must be connected to a local double pole isolation switch with a contact separation of at least 3mm. 7. The appliance must be earthed. 8. H200 Q Plus suitable for 230V ~ 50/60Hz single phase with a fuse rating of 3A. -

Owner's Manual Mini Mini Convertible

OWNER'S MANUAL MINI MINI CONVERTIBLE Cooper Congratulations on your new MINI Cooper S This Owner's Manual should be considered a permanent part of this vehicle. It should stay with the vehicle when sold to provide John Cooper the next owner with important operating, safety and mainte- Works nance information. We wish you an enjoyable driving experience. © 2010 Bayerische Motoren Werke Aktiengesellschaft Munich, Germany Reprinting, including excerpts, only with the written consent of BMW AG, Munich. US English VII/10, 09 10 500 Printed on environmentally friendly paper, bleached without chlorine, suitable for recycling. CONTENTS AT A GLANCE The fastest way to find information on a particu- Communication lar topic or item is by using the index, refer to 152 Telephone page 226. 164 Office 171 MINI Connected Using this Owner's Manual 4 Notes MOBILITY CONTROLS 6 Reporting safety defects 176 Refueling 178 Wheels and tires AT A GLANCE 187 Under the hood 10 Cockpit 191 Maintenance 16 On-board computer 193 Care 20 Letters and numbers 197 Replacing components 21 Voice activation system TIPS DRIVING 208 Giving and receiving assistance CONTROLS REFERENCE 26 Opening and closing 214 Technical data 41 Adjustments 219 Short commands for the voice activation 47 Transporting children safely system 50 Driving NAVIGATION 226 Everything from A to Z 59 Controls overview 71 Technology for driving comfort and safety 83 Lamps 87 Climate 92 Practical interior accessories DRIVING TIPS ENTERTAINMENT 100 Things to remember when driving NAVIGATION 110 Navigation system 111 Destination entry 119 Destination guidance Communication 126 What to do if… ENTERTAINMENT 130 On/off and tone 132 Radio MOBILITY 139 CD player 141 External devices REFERENCE 3 Notes Using this Owner's {...} Verbal instructions to use with the voice activation system. -

Military Master Light Switch Final Report

Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne Department of Engineering (ENGR 411) Military Master Light Switch Final Report Project Title: Military Master Light Switch Team Members: Andy David, Carlos Gonzalez, Andy McCormick, Deepali Rauniyard, and Nick Sorg Advisor: Dr. Wang, Dr. Zhao Date: April 28/2008 Table of Contents Date: April 28/2008 Table of Contents........................................................................................... 0 Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ 1 Table of Figures .............................................................................................................................. 2 Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................... 4 Abstract........................................................................................................................................... 5 Section I: Final Design................................................................................................................. 6 Housing Summary .................................................................................................................. 7 Pushbutton Summary.............................................................................................................. 7 Electrical Summary................................................................................................................ -

Switch Ratings, What's It All Mean?

Bob Nuckolls 6936 Bainbridge Road Wichita, Kansas 67226-1008 Voice/Fax: 316-685-8617 E-mail: [email protected] Switch Ratings, What's it all Mean? Just catching up on piles of snail-mail and e-mail that tends Quoting again from the article: to build up while we are flitting from fly-in to seminar. Picked up a copy of the Oct 97 issue of Van's Air Force and "Those of you who can still remember the old Kettering read an article on switch selection that makes some good coil ignition systems will recall that when the condenser in points but arrives at the wrong conclusion. The author was the distributor went bad, the points generally turned blue privileged to observe some work done at UL Laboratories and melted down in a few minutes. " on switches and expressed some concern for builder naivety with respect to AC versus DC ratings. The cited capacitor was to slow down a the rate-of-rise for voltage across relatively slow moving, cam driven switch He correctly cites an increased difficulty for breaking a DC contacts. If an arc were allowed to form between the circuit versus an AC circuit . particularly when inductive opening points, energy intended to spark combustible loads are involved. Quoting from the article: mixtures in a cylinder would be used up at the points instead . the most notable result of bad "condenser" was the car "Typical of this is the roller and bar micro switches made ran very badly if at all . the points were indeed subject to by MICRO(switch) Corporation.