South Indian Percussion in a Globalized India A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

“I Cannot Live Without Music”

INTERVIEW “I cannot live without music” Swati Tirunal was undoubtedly one of the most important modern composers, one who included Hindustani styles in his compositions. Nowadays it has become fashionable to say you must avoid Hindustani in Carnatic music or the other way around. But looking back, Bhimsen Joshi was among those south Indians who became luminaries in the north Indian style. How many south Indians are really open to Hindustani music is debatable. The late M.S. Gopalakrishnan was very competent in the Hindustani field, and my colleague Sanjay Subrahmanyan is a Carnatic musician open to Hindustani ragas – he sings a Rama Varma at the Swarasadhana workshop focussing on Swati Tirunal’s compositions pallavi in Bagesree, for instance. Then again there are ‘fundamentalist’ groups Well known Carnatic vocalist Rama Varma was in Chennai recently to who think Behag, Sindhubhairavi, conduct a two-day workshop (9 and 10 February 2013) Swarasadhana, Yamunakalyani, Sivaranjani and their at the Satyananda Yoga Centre at Triplicane. Here he speaks of the event, ilk should be totally done away with. his journey in classical music and his thoughts on the changing trends of the art form. Rama Varma How did Swarasadhana happen? in conversation with I have been teaching in a village called Perla near Mangalore for the past M. Ramakrishnan four years, at a music school called Veenavadini, run by the musician Yogeesh Sharma. He invites musicians to visit there once a year. Four years ago Veenavadini invited me. They enjoyed my teaching and Do you follow the same style of teaching I enjoyed being there too, and my visits became regular. -

Wish You All a Very Happy Diwali Page 2

Hindu Samaj Temple of Minnesota Oct, 2012 President’s Note Dear Community Members, Namaste! Deepavali Greetings to You and Your Family! I am very happy to see that Samarpan, the Hindu Samaj Temple and Cultural Center’s Newslet- ter/magazine is being revived. Samarpan will help facilitate the accomplishment of the Temple and Cultural Center’s stated threefold goals: a) To enhance knowledge of Hindu Religion and Indian Cul- ture. b) To make the practice of Hindu Religion and Culture accessible to all in the community. c) To advance the appreciation of Indian culture in the larger community. We thank the team for taking up this important initiative and wish them and the magazine the Very Best! The coming year promises to be an exciting one for the Temple. We look forward to greater and expand- ed religious and cultural activities and most importantly, the prospect of buying land for building a for- mal Hindu Temple! Yes, we are very close to signing a purchase agreement with Bank to purchase ~8 acres of land in NE Rochester! It has required time, patience and perseverance, but we strongly believe it will be well worth the wait. As soon as we have the made the purchase we will call a meeting of the community to discuss our vision for future and how we can collectively get there. We would greatly welcome your feedback. So stay tuned… Best wishes for the festive season! Sincerely, Suresh Chari President, Hindu Samaj Temple Wish you all a Very Happy Diwali Page 2 Editor’s Note By Rajani Sohni Welcome back to all our readers! After a long hiatus, we are bringing Samarpan back to life. -

Few Translation of Works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets Contents

Few translation of works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets I belong to Kerala but I did study Tamil Language with great interest.Here is translation of random religious works That I have done Contents Few translation of works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets ................. 1 1.Thiruvalluvar’s Thirukkual ...................................................................... 7 2.Vaan chirappu .................................................................................... 9 3.Neethar Perumai .............................................................................. 11 4.Aran Valiyuruthal ............................................................................. 13 5.Yil Vazhkai ........................................................................................ 15 6. Vaazhkkai thunai nalam .................................................................. 18 7.Makkat peru ..................................................................................... 20 8.Anbudamai ....................................................................................... 21 9.Virunthombal ................................................................................... 23 10.Iniyavai kooral ............................................................................... 25 11.Chei nandri arithal ......................................................................... 28 12.Naduvu nilamai- ............................................................................. 29 13.Adakkamudamai ........................................................................... -

Brahma Prakash Assistant Professor Theatre & Performance Studies Jnu, New Delhi-110067

BRAHMA PRAKASH ASSISTANT PROFESSOR THEATRE & PERFORMANCE STUDIES JNU, NEW DELHI-110067 Phone: (+91) 7838966326 Mailing Address [email protected] #007, School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, [email protected] New Delhi 110067 INDIA AREAS OF INTERESTS Theatre and Performance theories ‘Folk Culture’ from North India Ritual and Festival Studies Movement and Protest studies Marginalized Cultural Performances Non-Western Aesthetic with a special focus on Chinese, Japanese aesthetics WORK EXPERIENCE Assistant Professor, Theatre and Performance Studies, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi, 24 July 2015 to the Present. Visiting Faculty, Theatre and Performance Studies, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 18 Aug 2014 to 23 July 2015. Assistant Professor (tenured), Theatre and Performance Studies, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 12 July 2012 to 17 Aug 2014. Assistant Professor (adjunct), Centre for Media Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi (co-terminus) EDUCATION PhD University of London, UK, Theatre & Performance Studies Dec 2013 Dissertation: The Performance of Cultural Labour: Conceptualizing the Folk Performance in India MA National Central University, Taiwan, Chinese Aesthetics June 2008 Thesis: < [在「樂」和「舞」之間:一個中國和印度美學的比較研究]> “Between Natya and Yue: A Comparative Study of Indian and Chinese Aesthetics” MA Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, Arts and Aesthetics June 2005 (Theatre -

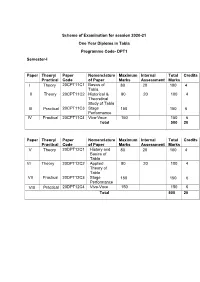

Scheme of Examination for Session 2020-21 One Year Diploma in Tabla Programme Code- DPT1 Semester-I Paper Theory/ Practical

Scheme of Examination for session 2020-21 One Year Diploma in Tabla Programme Code- DPT1 Semester-I Paper Theory/ Paper Nomenclature Maximum Internal Total Credits Practical Code of Paper Marks Assessment Marks I Theory 20CPT11C1 Basics of 80 20 100 4 Tabla II Theory 20CPT11C2 Historical & 80 20 100 4 Theoretical Study of Tabla III Practical 20CPT11C3 Stage 150 150 6 Performance IV Practical 20CPT11C4 Viva-Voce 150 150 6 Total 500 20 Paper Theory/ Paper Nomenclature Maximum Internal Total Credits Practical Code of Paper Marks Assessment Marks V Theory 20DPT12C1 History and 80 20 100 4 Basics of Tabla VI Theory 20DPT12C2 Applied 80 20 100 4 Theory of Tabla VII Practical 20DPT12C3 Stage 150 150 6 Performance VIII Practical 20DPT12C4 Viva-Voce 150 150 6 Total 500 20 The candidate has to answer five questions by selecting atleast one question from each Unit. Maximum Marks 80 Internal Assessment 20 marks Semester 1 Theory Paper - I Programme Name One Year Diploma Programme Code DPT1 in Tabla Course Name Basics of Tabla Course Code 20CPT11C1 Credits 4 No. of 4 Hours/Week Duration of End 3 Hours Max. Marks 100 term Examination Course Objectives:- 1. To impart Practical knowledge about Tabla. 2. To impart knowledge about theoretical aspects of Tabla in Indian Music. 3. To impart knowledge about Tabla and specifications of Taala 4. To impart knowledge about historical development of Tabal and it’s varnas(Bols) Course Outcomes 1. Students would able to know specifications of Tabla and Taalas 2. Students would gain knowledge about Historical development of Tabla 3. -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

Dasti Yoga © 2015 by Richard Merrill Dasti Yoga Is a Spiritual Practice of Devotion Through Craft and Art, As Well As Other Handwork

Dasti Yoga © 2015 by Richard Merrill Dasti Yoga is a spiritual practice of devotion through craft and art, as well as other handwork. The word dasti means “of the hand, or pertaining to the hand.”i It is associated with kriya yoga, or karma yoga, of which there are many variants. Lekh Raj Puriii defines Dasti Yoga as yoga “with the hands,” in such activities as the telling of rosary beads, as well as in the handcrafts and trades. Dasti yoga can involve any activity with the hands, from washing dishes to playing a violin sonata. It is the remembering of God while performing good and useful actions. Its relationship to karma yoga is in the performing of actions as worship, without any desire for benefit or rewardiii. Sri Swami Satchidananda quotes a Hindu saying, ‘ “Man me Ram, hath me kam.” “There is work in the hand, but Ram [God] in the mind.” iv This is the state of one who has realized the goal of Dasti yoga. One example of an ancient Dasti practice is Dasti Attam, or dasi attam, sacred temple dancing once performed as worship in southern India by devadasis, or “servants of God”v. Indira dasi, a classical dancer and authority on the history of the dance arts in India, writes in Classical Indian Temple Dancevi that the devas or demi-gods were sent to earth by their father to perform drama and dance in order to lift a curse that had been placed upon them. They founded the arts as they are known today. This is the mythic origin of the Indian classical dance form Bharatha Natyam, widely recognized as India’s national dance. -

November - December 2020 No

Society for Asian Art Newsletter for Members November - December 2020 No. 6 A Message from the SAA President Dear SAA Members and Friends, Have you noticed that time seems to be passing much faster, even though we are staying at home? Is it the lack of excitement, the lack of travels, or the shorter time between SAA Zoom Meetings and Webinars? I am happy to inform you that our events are so well attended that we are confident for the future and are going ahead enthusiastically with planning events to keep your mind and your interest in Asian art at full capacity. That is, after all, the mission of the SAA! November and December may have fewer events because of the many holidays and celebrations, but just look at the Spring 2021 Arts of Asia Lecture Series starting on January 22. Congratulations to the Arts of Asia Committee and our Instructor of Record, Mary-Ann Milford-Lutzker, for getting this together with such a thrilling list of scholars. The other committees have also been busy. Please sign up for our exciting programs in November and December, and be sure to save the dates for the 2021 trips. By now, many of you may have visited the Asian Art Museum since the re-opening on October 1, 2020, and contemplated your most loved works of art in person. We are fortunate to have this partial access to the special exhibitions and the collection galleries. While we await the opening of the new Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang Pavilion and the East West Bank Art Terrace, we are also waiting for access to Samsung Hall, the Loggia and Koret Education Center, spaces where we love to meet you in person, have live lectures and events, or even sell books. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations.