English L Essons Through Iterature L Samples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators

Page i 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators Page ii POPULAR AUTHORS SERIES The 100 Most Popular Young Adult Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. Revised First Edition. By Bernard A. Drew. Popular Nonfiction Authors for Children: A Biographical and Thematic Guide. By Flora R. Wyatt, Margaret Coggins, and Jane Hunter Imber. 100 Most Popular Children's Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. By Sharron L. McElmeel. 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. By Sharron L. McElmeel. Page iii 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies Sharron L. McElmeel Page iv Copyright © 2000 Sharron L. McElmeel All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Libraries Unlimited, Inc. P.O. Box 6633 Englewood, CO 801556633 18002376124 www.lu.com Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data McElmeel, Sharron L. 100 most popular picture book authors and illustrators : biographical sketches and bibliographies / Sharron L. McElmeel. p. cm. — (Popular authors series) Includes index. ISBN 1563086476 (cloth : hardbound) 1. Children's literature, American—Biobibliography—Dictionaries. 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. Illustrators—United States—Biography—Dictionaries. 4. Illustration of books—Biobibliography—Dictionaries. 5. Illustrated children's books—Bibliography. 6. Picture books for children—Bibliography. I. Title: One hundred most popular picture book authors and illustrators. -

The-Odyssey-Greek-Translation.Pdf

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

017 Harvard Classics

THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books soldier could see through the window how the peopL were hurrying out of the town to see him hanged —P«ge 354 THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. Folk-Lore and Fable iEsop • Grimm Andersen With Introductions and No/« Volume 17 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1909 BY P. F. COLLIER & SON MANUFACTURED IN U. *. A. CONTENTS ^SOP'S FABLES— PAGE THE COCK AND THE PEARL n THE WOLF AND THE LAMB n THE DOG AND THE SHADOW 12 THE LION'S SHARE 12 THE WOLF AND THE CRANE 12 THE MAN AND THE SERPENT 13 THE TOWN MOUSE AND THE COUNTRY MOUSE 13 THE FOX AND THE CROW 14 THE SICK LION 14 THE ASS AND THE LAPDOG 15 THE LION AND THE MOUSE 15 THE SWALLOW AND THE OTHER BIRDS 16 THE FROGS DESIRING A KING 16 THE MOUNTAINS IN LABOUR 17 THE HARES AND THE FROGS 17 THE WOLF AND THE KID 18 THE WOODMAN AND THE SERPENT 18 THE BALD MAN AND THE FLY 18 THE FOX AND THE STORK 19 THE FOX AND THE MASK 19 THE JAY AND THE PEACOCK 19 THE FROG AND THE OX 20 ANDROCLES 20 THE BAT, THE BIRDS, AND THE BEASTS 21 THE HART AND THE HUNTER 21 THE SERPENT AND THE FILE 22 THE MAN AND THE WOOD 22 THE DOG AND THE WOLF 22 THE BELLY AND THE MEMBERS 23 THE HART IN THE OX-STALL 23 THE FOX AND THE GRAPES 24 THE HORSE, HUNTER, AND STAG 24 THE PEACOCK AND JUNO 24 THE FOX AND THE LION 25 1 2 CONTENTS PAGE THE LION AND THE STATUE 25 THE ANT AND THE GRASSHOPPER 25 THE TREE AND THE REED 26 THE FOX AND THE CAT 26 THE WOLF IN SHEEP'S CLOTHING 27 THE DOG IN THE MANGER 27 THE MAN AND THE WOODEN GOD 27 THE FISHER 27 THE SHEPHERD'S -

Aesop's Fables

Masterpiece Library U) 13-444/52.95 AESOP’S FABLES COMPLETE AND UNABRIDGED AFABLESESOP’S Masterpiece Library MAGNUM BOOKS NEW YORK masterpiece library AESOP’S FABLES Special contents of this edition copyright © 1968 by Lancer Books, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the U.SA. CONTENTS The Fox and the Crow 11 The Gardener and His Dog 13 The Milkmaid and Her Pail 14 The Ant and the Grasshopper 16 The Mice in Council 17 The Fox and the Grapes 18 The Fox and the Goat 19 The Ass Carrying Salt 20 The Gnat and the Bull 22 The Hare with Many Friends 24 The Hare and the Hound 25 The House Dog and the Wolf 26 The Goose with the Golden Eggs 28 The Fox and the Hedgehog 29 The Horse and the Stag 31 The Lion and the Bulls 32 The Goatherd and the Goats 33 5 Androcles and the Lion 34 The Hare and the Tortoise 36 The Ant and the Dove 38 The One-Eyed Doe 39 The Ass and His Masters 40 The Lion and the Dolphin 42 The Ass’s Shadow 43 The Ass Eating Thistles 44 The Hawk and the Pigeons 45 The Belly and the Other Members 47 The Frogs Desiring a King 49 The Cat and the Mice 51 The Miller, His Son, and Their Donkey 53 The Ass, the Cock, and the Lion 55 The Hen and the Fox 57 The Lion and the Goat 58 The Fox and the Lion 59 The Crow and the Pitcher 60 The Boasting Traveler 61 The Eagle, the Wildcat, and the Sow 62 The Ass and the Grasshopper 64 The Heifer and the Ox 65 The Fox and the Stork 67 The Farmer and the Nightingale 69 The Ass and the Lap Dog 71 Jupiter and the Bee 73 The Horse and the Groom 75 The Mischievous Dog 76 The Blind Man and the Whelp 77 The -

Aesop's Fables

1-21 22-42 The Cock and the Pearl The Frog and the Ox The Wolf and the Lamb Androcles The Dog and the Shadow The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts The Lion's Share The Hart and the Hunter The Wolf and the Crane The Serpent and the File The Man and the Serpent The Man and the Wood The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse The Dog and the Wolf The Fox and the Crow The Belly and the Members The Sick Lion The Hart in the Ox-Stall The Ass and the Lapdog The Fox and the Grapes The Lion and the Mouse The Horse, Hunter, and Stag The Swallow and the Other Birds The Peacock and Juno The Frogs Desiring a King The Fox and the Lion The Mountains in Labour The Lion and the Statue The Hares and the Frogs The Ant and the Grasshopper The Wolf and the Kid The Tree and the Reed The Woodman and the Serpent The Fox and the Cat The Bald Man and the Fly The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing The Fox and the Stork The Dog in the Manger The Fox and the Mask The Man and the Wooden God The Jay and the Peacock The Fisher 43-62 63-82 The Shepherd's Boy The Miser and His Gold The Young Thief and His Mother The Fox and the Mosquitoes The Man and His Two Wives The Fox Without a Tail The Nurse and the Wolf The One-Eyed Doe The Tortoise and the Birds Belling the Cat The Two Crabs The Hare and the Tortoise The Ass in the Lion's Skin The Old Man and Death The Two Fellows and the Bear The Hare With Many Friends The Two Pots The Lion in Love The Four Oxen and the Lion The Bundle of Sticks The Fisher and the Little Fish The Lion, the Fox, and the Beasts Avaricious and Envious The Ass's Brains -

Aesop's Fables, However, Includes a Microsoft Word Template File for New Question Pages and for Glos- Sary Pages

1 æsop’s fables Click here to jump to the Table of Contents 2 Copyright 1993 by Adobe Press, Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. The text of Aesop’s Fables is public domain. Other text sections of this book are copyrighted. Any reproduction of this electronic work beyond a personal use level, or the display of this work for public or profit consumption or view- ing, requires prior permission from the publisher. This work is furnished for informational use only and should not be construed as a commitment of any kind by Adobe Systems Incorporated. The moral or ethical opinions of this work do not necessarily reflect those of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe Systems Incorporated assumes no responsibilities for any errors or inaccuracies that may appear in this work. The software and typefaces mentioned on this page are furnished under license and may only be used in accordance with the terms of such license. This work was electronically mastered using Adobe Acrobat software. The original composition of this work was created using FrameMaker. Illustrations were manipulated using Adobe Photoshop. The display text is Herculanum. Adobe, the Adobe Press logo, Adobe Acrobat, and Adobe Photoshop are trade- marks of Adobe Systems Incorporated which may be registered in certain juris- dictions. 3 Contents • Copyright • How to use this book • Introduction • List of fables by title • Aesop’s Fables • Index of titles • Index of morals • How to create your own glossary and question pages • How to print and make your own book • Fable questions Click any line to jump to that section 4 How to use this book This book contains several sections. -

Great Big Treasu Ry of Beatrix Potter Great Big Treasu Ry of Beatrix Potter

Picture here Great Big Treasury of Beatrix Potter By Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) Born in Victorian London on July 28th, 1866, Beatrix Potter created some of the best-loved children’s stories of all time. Starting with Peter Rabbit and moving through the rest of these delightful tales, the Great Big Treasury of Beatrix Potter will warm the hearts both of those who remember her fondly from their childhoods and those who discover for the first time the magic of these timeless stories. (Summary by Chip) Great Big Treasury of Beatrix TreasuryPotter Great Beatrix of Big 01 – The Tale of Peter Rabbit, read by Kara Shallenberg – 00:06:49 02 – The Tailor of Gloucester, read by Marilyn Saklatvala – 00:17:21 03 – The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, read by Sherry Crowther – 00:08:50 04 – The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, read by Geva – 00:06:33 05 – The Tale of Two Bad Mice, read by Hugh McGuire – 00:07:29 06 – The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, read by Jeremy – 00:09:13 07 – The Pie and the Patty-Pan, read by wedschild – 00:09:27 08 – The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, read by retswerb – 00:06:11 09 – The Story of a Fierce Bad Rabbit, read by Brad Bush – 00:01:23 10 – The Story of Miss Moppet, read by Betsie Bush – 00:02:06 11 – The Tale of Tom Kitten, read by Neils Clemenson – 00:05:13 12 – The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, read by Brad Bush – 00:07:57 13 – The Roly-Poly Pudding, read by Vlooi – 00:19:19 14 – The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies, read by Annie Coleman – 00:08:13 15 – The Tale of Mrs. -

Aesop's Fables

CHILDREN’S THRIFT CLASSICS AESOP’S FABLES Unabridged • In Easij-to-ReadTijpe Aesop _________________ CHILDRENS THRIFT CLASSICS Aesop’s Fables ILLUSTRATED BY Pat Stewart DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. New York DOVER CHILDREN’S THRIFT CLASSICS Editor of This Volume: Candace Ward Copyright Copyright © 1994 by Dover Publications, Inc. Illustrations copyright © 1994 by Pat Stewart. All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions. Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd., 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Toronto, Ontario. Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Ltd., 3 The Lanchesters, 162-164 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 9ER. Bibliographical Note Aesop’s Fables is a new selection of fables traditionally attributed to Aesop. The text has been adapted from Aesop’s Fables, Cassell & Company, Limited, London, n.d., and other standard editions. The illus trations and the note have been specially prepared for this edition. Library of Congress CataLoging-in-Picblication Data Aesop's fables. English. Selections Aesop’s fables / illustrated by Pat Stewart. p. cm.—(Dover children’s thrift classics) Summary: A collection of concise stories told by the Greek slave, Aesop. ISBN 0-486-28020-9 (pbk.) 1. Fables [1. Fables.] I.Aesop. II. Stewart, Pat Ronson, ill. III. Title. IV. Series. PZ8.2A254Ste 1994 [398.24'52]—dc20 ' 94-8782 CIP AC Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501 Contents The Ants and the Grasshopper 1 The Wolf in Sheep’s -

Aesop's Fables

AESOP’S FABLES BY AESOP © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc This PDF eBook was produced in the year 2008 by Tantor Media, Incorporated, which holds the copyright thereto. -

Aesop's and Other Fables

Aesop’s and other Fables Æsop’ s and other Fables AN ANTHOLOGY INTRODUCTION BY ERNEST RHYS POSTSCRIPT BY ROGER LANCELYN GREEN Dent London Melbourne Toronto EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY Dutton New York © Postscript, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1971 AU rights reserved Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford, Surrey for J. M. DENT & SONS LTD Aldine House, 33 Welbeck Street, London This edition was first published in Every matt’s Library in 19 13 Last reprinted 1980 Published in the USA by arrangement with J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd No 657 Hardback isbn o 460 00657 6 No 1657 Paperback isbn o 460 01657 1 CONTENTS PAGE A vision o f Æ sop Robert Henryson , . * I L FABLES FROM CAXTON’S ÆSOP The Fox and the Grapes. • • 5 The Rat and the Frog 0 0 5 The W olf and the Skull . • 0 0 5 The Lion and the Cow, the Goat and the Sheep • 0 0 6 The Pilgrim and the Sword • • 0 6 The Oak and the Reed . 0 6 The Fox and the Cock . , . 0 7 The Fisher ..... 0 7 The He-Goat and the W olf . • •• 0 8 The Bald Man and the Fly . • 0 0 8 The Fox and the Thom Bush .... • t • 9 II. FABLES FROM JAMES’S ÆSOP The Bowman and the Lion . 0 0 9 The W olf and the Crane . , 0 0 IO The Boy and the Scorpion . 0 0 IO The Fox and the Goat . • 0 0 IO The Widow and the Hen . 0 0 0 0 II The Vain Jackdaw ... -

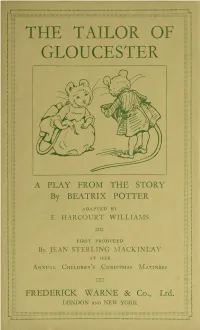

the Tailor of ;::: Gloucester

r=iii;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;iit .... THE TAILOR OF ;::: GLOUCESTER .. .. .... ... A PLAY FROM THE STORY By BEATRIX POTTER ADAPTED BY E. HARCOURT vVILLIAMS .... tltl . .. FIRST PRODUCED . By JEAN STERLING MACKINLAY .... AT HER .... ANNUAL CHILDREN'S CHRISTMAS MATINEES tlO .,. , · ... FREDERICK WARNE & Co., Ltd. LONDON AND NEW YORK : ::: ::: ::::: :: : : :: : ::: : :::::: :: ::: : :::::: :: :: : : ::: : : ::: ::: :: : ::: : ::: : :::: ::: :: : :: : : :: ::: :::: ::: :: ::: ::: : :: :: : : : ::::: ::: :: :: :: :: :: : : ::: :: . .. ······· .................. ' ... ................................. ... ..... ........................ .. ............. .... ....... ............ ... ...: ........................................................................................................................................: Where no fee for admission is charged, this play may be performed without permission or payment of any fee. If admission to the play is by payment, or by purchase of a programme, the permission of the Publishers must first be obtained and a fee paid. FREDERICK WARNE & CO., LTD., CHANDOS HousE, BEDFORD CouRT, LONDON, W.C.2. Price One Shilling Net. Printed in Great Britain for the Publishers by Glovers, 1Ves/011-s11per-!11arf'. THE TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER A PLAY From the tory b) BEATRIX POTTER Adapted by E . HARCOCRT \VILLIAMS FirfL produced by Jean Sterling Mackinlay al her :\nnual Children's Christmas :Matinees. CAST. The -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline .