A Case Study of the University of Blue Ridge Scholars and Persistence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Career and Certificate Programs of Study

AdditionalATLANTA METROPOLITAN transfer STATE COLLEGE 2019 – 2020 CATALOG Volume 37 Atlanta Metropolitan State College is committed to the principle of affirmative action and does not discriminate against persons on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, physical or mental handicap, disability or veteran status in its recruitment, admissions, employment, facility and program accessibility, or services. It is the responsibility of all students to read this catalog, official announcements, and official bulletin boards, and to otherwise inform themselves of all facts relating to life at the College. Each student will be held responsible for the contents of the catalog and other official announcements and publications of Atlanta Metropolitan State College. This catalog is prepared for the convenience of students and is not to be construed as a contract between a student and this institution. In case of any divergence from or conflict with the Bylaws or Policies of the Board of Regents, the official Bylaws and Policies of the Board of Regents shall prevail. While every effort is made to provide accurate and current information, Atlanta Metropolitan State College reserves the right to change, without notice, statements in the catalog concerning rules, policies, fees, curricula, courses, calendars or other matters. Students enrolled at Atlanta Metropolitan State College agree to comply with all College rules and regulations and with any necessary changes in these rules and regulations. Atlanta Metropolitan State College, in compliance with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of the 1974 “Buckley Amendment,” releases no personal information restricted by that Act without written consent of the student. -

Zone 3 – Atlanta Regional Commission

REGIONAL PROFILE ZONE 3 – ATLANTA REGIONAL COMMISSION TABLE OF CONTENTS ZONE POPULATION ........................................................................................................ 2 RACIAL/ETHNIC COMPOSITION ..................................................................................... 2 MEDIAN ANNUAL INCOME ............................................................................................. 3 EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT ...................................................................................... 4 GEORGIA COMPETITIVENESS INITIATIVE REPORT .................................................... 10 RESOURCES .................................................................................................................. 11 This document is available electronically at: http://www.usg.edu/educational_access/complete_college_georgia/summit ZONE POPULATION 2011 Population 4,069,211 2025 Projected Population 5,807,337 Sources: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2011 ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, 5-year estimate Georgia Department of Labor, Area Labor Profile Report 2012 RACIAL/ETHNIC COMPOSITION Source: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2011 ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, 5-year estimate 2 MEDIAN ANNUAL INCOME Source: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2010, Selected Economic Characteristics, 5-year estimate 3 EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION RATES SYSTEM NAME 2011 GRADUATION RATE (%) Decatur City 88.40 Buford City 82.32 Fayette 78.23 Cherokee 74.82 Cobb 73.35 Henry -

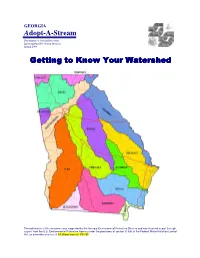

Watershed.Pdf

GEORGIA Adopt-A-Stream Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Spring 2008 Getting to Know Your Watershed The publication of this document was supported by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division and was financed in part through a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under the provisions of section 319(h) of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, as amended at a cost of $4.30 per manual. 5/01/08 Georgia’s 52 M ajor Watersheds Map by the Geologic Survey Branch, Environmental Protection Division Provided to the Georgia Water Management Campaign Watershed boundaries from United States Geological Survey 8 digit Hydrologic Cataloging Units Watershed names from Water Protection Branch, Environmental Protection Division Cover: Georgia’s 14 major river basins 2 Georgia Adopt-A-Stream 4220 International Parkway, Suite 101 Atlanta, Georgia 30354 (404) 675-6240 www.GeorgiaAdoptAStream.org 3 Acknowledgements This manual draws on the experience of many wonderful citizen monitoring, stewardship and education programs. Representatives from every region of the State provided support. Georgia Adopt-A-Stream gratefully acknowledges the following organizations for their advice and use of materials: Special Contributions: EPD Water Protection Branch, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service North Georgia Piedmont Region Fulton County Adopt-A-Stream, DeKalb County Adopt-A-Stream, Upper Chattahoochee River Keeper, Peavine Watershed Alliance, North Georgia College and State University, Keep Georgia Beautiful, -

Where Metro Meets the Mountains” “Where Metro Meets the Mountains”

Destination Cherokee Georgia To Chattanooga, TN Cherokee One of the fastest growing counties in Georgia, Cherokee County is a short drive from Metro-Atlanta and the North Georgia Mountains. With its natural beauty, County cultural richness, vibrant communities and southern hospitality, Cherokee County is not only a great place to live - it is a great place to visit! 75 575 EXPLORE GARDENS, ARTS AND HISTORY 400 • Gibbs Gardens • Historic Walking Tours, Heritage Center and Visitor Centers To Greenville, SC • Art Museums, Performing Arts Centers and Sculpture Garden • The Georgia National Cemetery 285 85 ENJOY SPORTS AND OUTDOOR ADVENTURE • Family Aquatic Parks and Indoor Olympic Pools ATLANTA • Water Activities on the Etowah River and Lake Allatoona • Miles of Mountain Bike, Hiking and Equestrian Trails To Augusta, GA To Birmingham, AL 20 • Exceptional Public Golf Courses and Acres of Parks & Playgrounds 285 • Acclaimed Dirt Speedway, Duck Hunting Preserve and Sporting Clays SHOP UNTIL YOU DROP • The Outlet Shoppes at Atlanta 85 • Cabela’s, the World’s Foremost Outfitter 75 • Specialty shops, antique stores and unique boutiques galore in To Montgomery, AL Downtown Main Street Districts and surrounding communities INDULGE IN CULINARY DELIGHTS • Award Winning Restaurants • Famous Eateries, Delicatessens and Southern Barbeque To Orlando, FL • Vineyards, Breweries, Growlers, Coffee Shops and Bakeries “Where Metro Meets the Mountains” “Where Metro Meets the Mountains” Photo credits include PhotoJack.net/Jack Tuszynski, Woodstock CVB, Advertising Dynamics, Inc., Joe Cook, Rick Cannon, Kris Pinyan, Dwight Waggener, Brent Templeton, MOJO Productions, Rolling Thunder Enterprises, Service League of Cherokee County, The Outlet Shoppes at Atlanta, Wiley Creek Duck Preserve, Cherokee Recreation & Parks Agency and Reformation Brewery. -

A History of Appalachia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 2-28-2001 A History of Appalachia Richard B. Drake Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Drake, Richard B., "A History of Appalachia" (2001). Appalachian Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/23 R IC H ARD B . D RA K E A History of Appalachia A of History Appalachia RICHARD B. DRAKE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the E.O. Robinson Mountain Fund and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2003 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kenhlcky Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drake, Richard B., 1925- A history of Appalachia / Richard B. -

A History and Analysis of the Lend-A-Hand Center in the Stinking Creek Community of Knox County, Kentucky

TO LEND A HAND: A HISTORY AND ANALYSIS OF THE LEND-A-HAND CENTER IN THE STINKING CREEK COMMUNITY OF KNOX COUNTY, KENTUCKY A Thesis by KATHRYN S. ENGLE Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2013 Department of Appalachian Studies TO LEND A HAND: A HISTORY AND ANALYSIS OF THE LEND-A-HAND CENTER IN THE STINKING CREEK COMMUNITY OF KNOX COUNTY, KENTUCKY A Thesis by KATHRYN S. ENGLE August 2013 APPROVED BY: Bradley Nash, Jr., Ph.D. Chairperson, Thesis Committee Bruce Stewart, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Alan Banks, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Patricia Beaver, Ph.D. Chairperson, Department of Appalachian Studies Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Cratis Williams Graduate School Copyright by Kathryn S. Engle 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract TO LEND-A-HAND: A HISTORY AND ANALYSIS OF THE LEND-A-HAND CENTER IN THE STINKING CREEK COMMUNITY OF KNOX COUNTY, KENTUCKY Kathryn S. Engle B.B.A., Eastern Kentucky University B.A., Eastern Kentucky University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Bradley Nash, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis documents the history of the Lend-A-Hand Center, Inc., a nonprofit community service provider in Knox County, Kentucky, that has served the Stinking Creek watershed since 1958. The brainchild and lifework of two women from the North, Irma Gall and Peggy Kemner, the Lend-A-Hand Center has become an influential organization in the region and has had a significant impact on the Stinking Creek community. Although the Center has been intertwined with many important movements, events, and organizations in Appalachia, it has not previously been the subject of any serious academic study. -

Native Plants North Georgia

Native Plants of North Georgia A photo guide for plant enthusiasts Mickey P. Cummings · The University of Georgia® · College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences · Cooperative Extension CONTENTS Plants in this guide are arranged by bloom time, and are listed alphabetically within each bloom period. Introduction ................................................................................3 Blood Root .........................................................................5 Common Cinquefoil ...........................................................5 Robin’s-Plantain ..................................................................6 Spring Beauty .....................................................................6 Star Chickweed ..................................................................7 Toothwort ..........................................................................7 Early AprilEarly Trout Lily .............................................................................8 Blue Cohosh .......................................................................9 Carolina Silverbell ...............................................................9 Common Blue Violet .........................................................10 Doll’s Eye, White Baneberry ...............................................10 Dutchman’s Breeches ........................................................11 Dwarf Crested Iris .............................................................11 False Solomon’s Seal .........................................................12 -

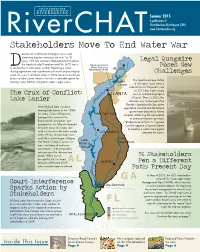

Stakeholders Move to End Water War

Summer 2015 A publication of Chattahoochee Riverkeeper (CRK) RiverCHAT www.chattahoochee.org Stakeholders Move To End Water War ecades of conflict over Georgia’s most used waterway may be coming to an end. For 21 years, CRK has worked collaboratively throughout Legal Quagmire the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) basin Poses New toD resolve the tri-state water conflict. Reaching a water sharing agreement that is protective of human and ecological Challenges needs for users in all three states is critical because continued access to Lake Lanier remains the most sustainable option for The legal landscape shifted meeting metro Atlanta’s long-term water supply needs. in Georgia’s favor when a federal Court of Appeals ruled in 2011 that water supply The Crux of Conflict: was an authorized purpose of Lanier. Then, in 2013, this Lake Lanier decision was challenged when Florida’s Apalachicola Bay oyster When Buford Dam was built, population crashed and the federal forming Lake Lanier in the 1950s, government declared a fishery the Army Corps of Engineers disaster. Attributing the devastation managed the reservoir for to overconsumption upstream, flood control, navigation and Florida turned to the U.S. Supreme hydropower. As Atlanta’s demand Court to appoint a Special Master for water grew, the Corps also to develop a water-sharing plan used the reservoir for water supply. between the states. In the 1970s, downstream users in all three states began alleging that North Georgia’s water use was unauthorized and over consumptive, with inequitable consequences for downstream needs. When severe 56 Stakeholders drought hit the Southeast between 2006 and 2009, Pen a Different these tensions came to a head. -

Robert Scott Davis

Robert S. Davis Biography and Bibliography 2/25/2011 Robert Scott Davis Director, Family & Regional History Program http://www.wallacestate.edu/genealogy/index.html Professor, Genealogy, Geography, & History Robert Scott Davis Full biography and bibliography: http://www3.wallacestate.edu/bobdavis/index.html ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Director, Family & Regional History Program Professor of Genealogy, Geography, & History Wallace State College Home: P. O. Box 2000 P. O. Box 687 801 N. Main Street Hanceville, AL 35077-0687 USA Hanceville, Alabama 35077-2000 USA Phone: (205) 429-5251 E mail: [email protected] Office Phone: (256) 352-8265 Office E mail: [email protected] Robert Scott "Bob" Davis is a family and regional history expert and senior faculty member in the History Department at Wallace State Community College, Hanceville, Alabama. His program pioneers local and family history research in a college environment. He holds a Master of Education degree in history from North Georgia College and a Master of Arts degree from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Bob is also a graduate of the Institute of Documentary Editing of the National Historical Records Publications Commission. His more than 1,000 publications on records and research include a number of books and more than 100 articles and reviews in professional historical, library, education, and archival journals, including Prologue: The Quarterly of the National Archives, Gulf States Historical Review, Journal of African-American History, Agricultural History, The Journal of Military History, Documentary Editing, The Journal of Southern Legal History, The Alabama Review, Georgia Historical Quarterly, and The South Carolina Historical Magazine. Robert S. Davis has been quoted in Time, Smithsonian, CNN, NPR, NBC, The Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal. -

From the War on Poverty to Grassroots Feminism in the Appalachian South

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository WHERE MOVEMENTS MEET: FROM THE WAR ON POVERTY TO GRASSROOTS FEMINISM IN THE APPALACHIAN SOUTH Jessica Wilkerson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of doctor of philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Laura Edwards James L. Leloudis Nancy MacLean Zaragosa Vargas ©2014 Jessica Wilkerson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jessica Wilkerson: Where Movements Meet: From the War on Poverty to Grassroots Feminism in the Appalachian South (Under the direction of Jacquelyn Dowd Hall) This dissertation traces the alliances forged and the grassroots movements led by women in the Appalachian South in the 1960s and 1970s, with a focus on eastern Kentucky. With a wide variety of sources, including oral history interviews, archival film footage, memorabilia, local and underground publications, and manuscript collections, it shows how women shaped the federal War on Poverty in Appalachia and then used the skills they learned in antipoverty programs to foster social justice activism that continued in the 1970s and beyond. Women in Appalachia, who have seldom been seen as actors in the movements of the 1960s, were key leaders and foot soldiers in what contemporaries called the Appalachian Movement, which intersected with civil rights organizations and had its roots in the War on Poverty. Rural, poor and working-class women helped to shape debates about welfare rights, women’s rights, and labor justice in the 1960s and 1970s, connecting white and black women, insiders and outsiders, to form a robust, interracial, intergenerational, and region-wide movement. -

Chattooga Quarterly

Chattooga Quarterly WWinterinter ♦♦♦♦♦♦ 22018018 / 22019019 T G George Cooke’s 1841 painting showcases three waterfalls of Tallulah Gorge. Artwork c/o GA Museum of Art, UGA; Gift of Mrs. William Lorenzo Moss I N S I D E Director’s Page..............................................2 The Drought of 1925.....................................7 Trillium persistens.........................................3 Watershed Update........................................12 Tallulah Gorge...............................................4 Members’ Pages...........................................17 2 Chattooga Quarterly Director’s Page Nicole Hayler might be a reasonable forestry project. However, there are several issues that we're concerned about: A literal tsunami swept over the Chattooga River during 2018, in the form of record-breaking, relentless rainfall throughout • Front and center is the use of clear-cuts, which is the much of the watershed. Now looking ahead, I fear that a even-age tree harvesting technique that the Forest Service fi gurative tsunami may befall the Chattooga watershed in 2019. is expected to use on 1,400 acres. Clearcutting is an For an inkling of what this might be, see this publication’s extremely heavy-handed forestry treatment, which causes “watershed update” section: Cashiers Lake development, major habitat disruption and destruction. The denuded Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan Revision, Foothills Landscape lands are also much more susceptible to developing erosion project, loblolly pine clearcutting, and sedimentation issues. -

Workforce Readiness Access to Education Partnerships & Collaboration Reed Task Force 5

TASK FORCE SUMMARY • FEBRUARY 2014 WORKFORCE ACCESS TO PARTNERSHIPS & READINESS EDUCATION COLLABORATION 2 “By 2020, it is projected that over 60 percent of jobs in Georgia will require some form of a college education, whether a certificate, associate’s degree, or bachelor’s degree. Today, only 42 percent of the state’s young adults, its burgeoning workforce, qualify.” —Complete College Georgia “The REED Project is a unique opportunity for the university system to support innovation, entrepreneurship, and business development in our communities.” —Mark Lytle, Vice Chancellor for Economic Development University System of Georgia “Facilitating the REED Task Force Meetings and Summit allowed me to truly experience the collective spirit of the Northeast Georgia region. It is this unity of purpose–increasing educational opportunities and strengthening local economies–that makes the REED initiative so important. It will require an intentional effort to maintain the momentum, but our communities are worth it.” —Dr. Janet Marling National Institute for the Study of Transfer Students “It is vitally important that our regional education and community leaders work in partnership to identify the needs of our region and the resources necessary to achieve our goals.” —Dr. Bonita C. Jacobs, President University of North Georgia 3 Greetings, Friends of the Northeast Georgia Region, The Complete College Georgia initiative has revealed an alarming statistic: only 17 percent of Georgia’s public high school freshmen will graduate on time from a two- or four-year college or university. In addition, many of our young people are not prepared to join the workforce of tomorrow. To address these issues and positively CONTENTS impact the future of our region, the University INTRODUCTION 3 of North Georgia established the Regional Education and Economic TASK FORCE MEETINGS 4 Development (REED) Task Force, a partnership of more than 100 THEMES FOR CHANGE invited business, education, government, and community leaders from a 27-county area of the northeast region of the state.