Jerusalem: the Rising Cost of Peace February 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport Des Chefs De Mission Diplomatiques De L'union

Rapport des Chefs de Mission Diplomatiques de l’Union Européenne sur Jérusalem 2017 Note de synthèse Les Chefs de Mission à Jérusalem et à Ramallah soumettent par le présent document au Comité Politique et de Sécurité le rapport sur Jérusalem pour 2017 (annexe 1) et une série de recommandations pour discussion pour renforcer la politique de l’Union Européenne sur Jérusalem Est (Annexe 2). L’annexe 3 contient des faits supplémentaires et des chiffres sur Jérusalem. Les développements intervenus en 2017 ont encore accéléré les difficultés de la solution « des deux Etats » en l’absence de processus de paix significatif. Les tendances précédentes, observées et décrites par les Chefs de Mission Diplomatiques depuis plusieurs années, se sont empirées. La mise à l’écart des Palestiniens de la vie ordinaire, politique, économique et sociale de la ville sont largement inchangées. Le développement d’un nombre record de plans de colonisation s’est poursuivi, y compris dans des zones identifiées par l’Union Européenne et ses Etats membres comme clés pour une solution « des deux Etats ». En même temps, les démolitions de logements palestiniens se sont poursuivies, et plusieurs familles palestiniennes ont été expulsées de leurs logements au bénéfice de colons. Les tensions autour du Dôme du Rocher / Mont du Temple continuent. Au cours de cette année, plusieurs projets de lois à la Knesset ont poursuivi leur avancée législative, qui, s’ils étaient adoptés, apporteraient des changements unilatéraux au statut et aux frontières de Jérusalem, en violation du droit international. En fin d’année, les Etats Unis ont annoncé leur reconnaissance de Jérusalem comme capitale d’Israël. -

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

HOUSTON REAL ESTATE MISSION to ISRAEL March 3-9, 2018

Program dated: May 24, 2017 HOUSTON REAL ESTATE MISSION TO ISRAEL March 3-9, 2018 D a y O n e : Saturday, March 3, 2018 DEPARTURE . Depart the U.S.A. Overnight: Flight D a y T w o : Sunday, March 4, 2018 TLV 24/7 . 12:00 p.m. Meet your tour educator in the hotel lobby. Enjoy lunch at Blue Sky, with it’s a wide selection of fish, vegetables, olive oil and artisan cheese, accompanied with local wines and overlooking the stunning views of the Mediterranean Sea. A Look into Our Journey: Tour orientation with the Mission Chair and the tour educator. The Booming Tel Aviv Real Estate Market: Take a tour of various locations around Tel Aviv with Ilan Pivko, a leading Israeli Architect and entrepreneur. Return to the hotel. Cocktails overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. Combining Business Abroad and Real Estate in Israel: Dinner at 2C with Danna Azrieli, the Acting Chairman of The Azrieli Group, at the Azrieli Towers. Overnight: Tel Aviv D a y T h r e e : Monday, March 5, 2018 FROM RED ROOFTOPS TO HIGH-RISERS . The Laws of Urban Development in Israel: Private breakfast at the hotel with Dr. Efrat Tolkowsky, CEO of the Gazit-Globe Real Estate Institute at IDC. Stroll down Rothschild Boulevard to view examples of the intriguing Bauhaus-style architecture from the 1930s; the local proliferation of the style won Tel Aviv recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage site and the nickname of ‘the White City'. Explore the commercial and residential developments with Dr. Micha Gross, the head of the Tel Aviv Bauhaus Center. -

Legal and Administrative Matters Law from 1970

Systematic dispossession of Palestinian neighborhoods in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan For many years, there has been an organized governmental effort to take properties in East Jerusalem from Palestinians and transfer them to settlers. In the past it was mainly through the Absentee Properties Law, but today the efforts are done mainly by the use of the Legal and Administrative Matters Law from 1970. Till recently this effort was disastrous for individual families who lost their homes, but now the aim is entire neighborhoods (in Batan al-Hawa and Sheikh Jarrah). Since the horrifying expulsion of the Mughrabi neighborhood from the Old City in 1967 there was no such move in Jerusalem. In recent years there has been an increase in the threat of expulsion hovering over the communities of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan in East Jerusalem. A wave of eviction lawsuits is being conducted before the courts, with well-organized and well-funded settler groups equipped with direct or indirect assistance from government agencies and the Israeli General Custodian. • Sheikh Jarrah - Umm Haroun (west of Nablus Road) - approximately 45 Palestinian families under threat of evacuation; At least nine of them are in the process of eviction in the courts and at least five others received warning letters in preparation for an evacuation claim. Two families have already been evacuated and replaced by settlers. See map • Sheikh Jarrah - Kerem Alja'oni (east of Nablus Road) – c. 30 Palestinian families under threat of evacuation, at least 11 of which are in the process of eviction in the courts, and 9 families have been evicted and replaced by settlers. -

Campaign to Preserve Mamilla Jerusalem Cemetery

PETITION FOR URGENT ACTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY ISRAEL Campaign to Preserve Mamilla Jerusalem Cemetery www.mamillacampaign.org Copyright 2010 by Campaign to Preserve Mamilla Jerusalem Cemetery www.mammillacampaign.org PETITION FOR URGENT ACTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY ISRAEL: DESECRATION OF THE MA’MAN ALLAH (MAMILLA) MUSLIM CEMETERY IN THE HOLY CITY OF JERUSALEM TO: 1.The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (Ms. Navi Pillay) 2. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion and Belief (Ms. Asma Jahangir) 3. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (Mr. Githu Muigai) 4. The United Nations Independent Expert in the Field of Cultural Rights (Ms. Farida Shaheed) 5. Director-General of United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (Ms. Irina Bokova) 6. The Government of Switzerland in its capacity as depository of the Fourth Geneva Conventions INDIVIDUAL PETITIONERS: Sixty individuals whose ancestors are interred in Mamilla (Ma’man Allah) Cemetery, from the Jerusalem families of: 1. Akkari 2. Ansari 3. Dajani 4. Duzdar 5. Hallak 6. Husseini 7. Imam 8. Jaouni 9. Khalidi 10. Koloti 11. Kurd 12. Nusseibeh 13. Salah 14. Sandukah 15. Zain CO- PETITIONERS: 1. Mustafa Abu-Zahra, Mutawalli of Ma’man Allah Cemetery 2. Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association 3. Al-Mezan Centre for Human Rights 4. Al-Dameer Association for Human Rights 5. Al-Haq 6. Al-Quds Human Rights Clinic 7. Arab Association for Human Rights (HRA) 8. Association for the Defense of the Rights of the Internally Displaced in Israel (ADRID) 9. -

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank Razi Nabulsi* “This road leads to Area “A” under the Palestinian Authority. The Entrance for Israeli Citizens is Forbidden, Dangerous to Your Lives, And Is Against The Israeli Law.” Anyone entering Ramallah through any of the Israeli military checkpoints that surround it, and surround its environs too, may note the abovementioned sentence written in white on a blatantly red sign, clearly written in three languages: Arabic, Hebrew, and English. The sign practically expires at Attara checkpoint, right after Bir Zeit city; you notice it as you leave but it only speaks to those entering the West Bank through the checkpoint. On the way from “Qalandia” checkpoint and until “Attara” checkpoint, the traveller goes through Qalandia Camp first; Kafr ‘Aqab second; Al-Amari Camp third; Ramallah and Al-Bireh fourth; Sarda fifth; and Birzeit sixth, all the way ending with “Attara” checkpoint, where the red sign is located. Practically, these are not Area “A” borders, but also not even the borders of the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate, neither are they the West Bank borders. This area designated by the abovementioned sign does not fall under any of the agreed-upon definitions, neither legally nor politically, in Palestine. This area is an outsider to legal definitions; it is an outsider that contains everything. It contains areas, such as Kafr ‘Aqab and Qalandia Camp that belong to the Jerusalem municipality, which complies -

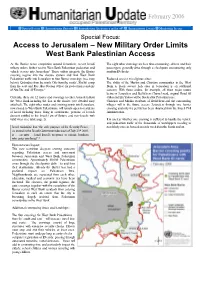

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

My Aunt's Mamilla

My father’s eldest sister has always served in My Aunt’s Mamilla my mind as a potential family encyclopedia. Helga Tawil-Souri “Potential” because I never had the opportunity to spend much time with her. She had come and visited us in Beirut once in the mid 1970s – I vaguely remember. My grandmother, with whom I spent much of my childhood, would often mention Auntie M. under a nostalgic haze, perhaps regret, that her first-born was so far away. That longing tone for her eldest led my other aunts, my father, and my uncles to joke that Auntie M. was their mother’s favorite. For years Auntie M. endured only in my imagination. Whatever tidbits I had caught about her were extraordinary, a fusion of new world mystery and old world obscurity. She lived in faraway places that sounded utterly exotic: Sao Paolo, Etobicoke, Toronto; that they always rhymed only added to their enigma. The haphazard trail I constructed of her life seemed improbable too: old enough to remember family life in Jerusalem; married and sent off to Brazil; had a daughter ten years older than me who didn’t speak Arabic. Auntie M. hovered behind a veil of unanswered questions: How old was she? Did my grandparents marry her off or did she choose to wed Uncle A.? How is one “sent” to Brazil? Could one even fly to Brazil back then? Did she flee with the family to Lebanon first? Did she really have another daughter besides the one I knew of? What happened to the other daughter? How did Auntie M. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

Armenian Christians in Jerusalem: 1700 Years of Peaceful Presence*

Laury Haytayan1 Прегледни рад Arab Region Parliamentarians Against Corruption UDK:27(479.25)(569.44) ARMENIAN CHRISTIANS IN JERUSALEM: 1700 YEARS OF PEACEFUL PRESENCE* Abstract This paper examines the presence of the Armenians in Jerusalem for the past 1700 years. This historical account sheds the light on the importance of Jerusa- lem for the Armenians, especially for the Armenian Church that was granted the authority to safeguard the Holy Places in the Holy Land with the Greek and Latin Churches. During the centuries, the Armenians survived all the conquests and were able to find all sorts of compromises with all the different powers that conquered Jerusalem. This study shows that the permanent presence is due to the wise religious authorities and the entire Armenian community who had no backing from super powers but they had their religious beliefs and their per- sistence in safeguarding the Holy Places of Christianity. The author takes the reader back in History by stopping at important events that shaped the history of the Armenians in the Holy Land. Key words: Jerusalem, Armenians, Crusaders, Holy Land, St James Monas- tery, Old City, Armenian Quarter. Introduction This paper comes at a time when Christians in Iraq and Egypt are being mas- sacred in their churches, Christians in Nazareth are being forbidden to decorate a Christmas tree in public space, and Christians in Lebanon are seeking to pre- serve their political rights to safeguard their presence in their Homeland. At a time, when the Palestinian Authority is alerting the International Community of the danger of the continuous and ferocious settlement construction in East Jerusalem by the State of Israel, and at a time when Christians of the East are being silent on the fate of Jerusalem by leaving it in the hands of the Palestinian and Israeli negotiators, hoping that the Unites States will be the caretaker of the Christians of Jerusalem. -

The Development of Modern Sacred Geography: Jerusalem's Holy Basin

Electronic Working Papers Series www.conflictincities.org/workingpapers.html Divided Cities/Contested States Working Paper No. 19 The Development of Modern Sacred Geography: Jerusalem’s Holy Basin Wendy Pullan and Maximilian Gwiazda Department of Architecture University of Cambridge Conflict in Cities and the Contested State: Everyday life and the possibilities for transformation in Belfast, Jerusalem and other divided cities UK Economic and Social Research Council Large Grants Scheme, RES-060-25-0015, 2007-2012. Divided Cities/Contested States Working Paper Series www.conflictincities.org/workingpapers.html Editor: Prof James Anderson Associate Editors: Prof Mick Dumper, Prof Liam O'Dowd and Dr Wendy Pullan Editorial Assistant: Dr Milena Komarova Correspondence to: [email protected]; [email protected] [Comments on published Papers and the Project in general are welcomed at: [email protected] ] THE SERIES 1. From Empires to Ethno-national Conflicts: A Framework for Studying ‘Divided Cities’ in ‘Contested States’ – Part 1, J. Anderson, 2008. 2. The Politics of Heritage and the Limitations of International Agency in Divided Cities: The role of UNESCO in Jerusalem’s Old City, M. Dumper and C. Larkin, 2008. 3. Shared space in Belfast and the Limits of A Shared Future, M. Komarova, 2008. 4. The Multiple Borders of Jerusalem: Implications for the Future of the City, M. Dumper, 2008. 5. New Spaces and Old in ‘Post-Conflict’ Belfast, B. Murtagh, 2008. 6. Jerusalem’s City of David’: The Politicisation of Urban Heritage, W. Pullan and M. Gwiazda, 2008. 7. Post-conflict Reconstruction in Mostar: Cart Before the Horse, Jon Calame and Amir Pasic, 2009.