Aircraft As an Investment Opportunity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disclosure Pursuant to 11 U.S.C

IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION In re: ) Chapter 11 ) UAL CORPORATION et al., ) Case No. 02-B-48191 ) (Jointly Administered) Debtors. ) ) Honorable Eugene R. Wedoff ) DEBTORS’ DISCLOSURE PURSUANT TO 11 U.S.C. § 1129(A)(5)(B) The above-captioned debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Reorganizing Debtors”), by and through their undersigned counsel, hereby file the Debtors’ Disclosure Pursuant to 11 U.S.C. § 1129(a)(5)(B). 1. The Reorganizing Debtors hereby disclose that on and after the Effective Date the individuals identified on Exhibit A will serve as the officers and directors of the Reorganized Debtors except UAL Corporation and officers of UAL Corporation. 2. The Reorganizing Debtors hereby disclose the nature of the Reorganizing Debtors’ management compensation on Exhibit B. 3. The Reorganizing Debtors will supplement this disclosure with information relating to the Reorganized UAL Board of Directors in advance of the confirmation hearing. Dated: Chicago, Illinois Respectfully submitted, January 10, 2006 By: /s/ Chad J. Husnick James H.M. Sprayregen, P.C. (ARDC No. 6190206) Marc Kieselstein (ARDC No. 6199255) David R. Seligman (ARDC No. 6238064) James J. Mazza Jr, (ARDC No. 6275474) Chad J. Husnick (ARDC No. 6283129) Kirkland & Ellis LLP 200 East Randolph Drive Chicago, IL 60601 (312) 861-2000 (telephone) (312) 861-2200 (facsimile) Counsel for Debtors and Debtors in Possession K&E 10903192.1 Exhibit A UAL CORPORATION Officers Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer Glenn F. Tilton Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Frederic F. Brace Executive Vice President Douglas A. -

United Continental Holdings, Inc. United Airlines, Inc

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on April 24, 2015 Registration No. 333- U.S. SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM S-3 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 United Continental Holdings, Inc. United Airlines, Inc. (Exact name of registrant issuer (Exact name of registrant issuer as specified in its charter) as specified in its charter) Delaware Delaware (State or other jurisdiction of (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) incorporation or organization) 36-2675207 74-2099724 (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number) (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number) 233 S. Wacker Drive 233 S. Wacker Drive Chicago, Illinois 60606 Chicago, Illinois 60606 (872) 825-4000 (872) 825-4000 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of Registrant’s principal executive offices) Brett J. Hart Executive Vice President and General Counsel United Continental Holdings, Inc. 233 S. Wacker Drive Chicago, Illinois 60606 (872) 825-4000 (Name, address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of agent for service) With a copy to: John K. Hoyns Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP One Battery Park Plaza New York, New York 10004 (212) 837-6000 Approximate date of commencement of proposed sale to the public: From time to time after this registration statement becomes effective. If the only securities being registered on this Form are being offered pursuant to dividend or interest reinvestment plans, please check the following box: o If any of the -

Team Captain Guide AIDS Run & Walk Chicago Saturday, October 2, 2010

Team Captain Guide AIDS Run & Walk Chicago Saturday, October 2, 2010 AIDS Run & Walk Chicago 2010 Saturday, October 2, 2010 Grant Park Team Captain Guide Table of Contents What is AIDS Run & Walk Chicago……………………………………. 3 Event Details ..………………………………………………………………….. 4 Preparing for Event Day …………………………………………………… 5 Team Building Tips …………………………………………………………… 6 Fundraising Tools ….…………………………………………………………. 7 Team Information Form …..………………………………………………. 8 Team Supplies Form ………………………………………………………… 9 Fundraising Form ……………………….……………………………………. 10 Online Fundraising Road Map ….……………………….…………….. 11 Participant Registration Form ………………………………………….. 12 Volunteer Information……………………………………………………… 13 Matching Gift Companies ………………………………………………… 14 2 About AIDS Run & Walk Chicago What is AIDS Run & Walk Chicago? AIDS Run & Walk Chicago is the largest AIDS-based outdoor fundraising event in the Midwest. Since its inception in 2001, AIDS Run & Walk Chicago has raised more than $3 million net to fight HIV/AIDS throughout the Chicagoland area. In 2009, more than 200 Teams joined forces to walk, run, and raise money in the fight against AIDS. With your help, we can surpass our goal of registering more than 300 Teams and raising $500,000 net! The AIDS Run & Walk Chicago Course takes place along the city’s lakefront, featuring Chicago’s famous skyline. Whether your teammates decide to run or walk along this spectacular course, all participants will be provided with the official AIDS Run & Walk Chicago T-Shirt, Race Bib, entertainment along the course, pre and post event activities, as well as lunch and treats! What Organizations Benefit from AIDS Run & Walk Chicago? AIDS Run & Walk Chicago benefits the AIDS Foundation of Chicago (AFC). AFC is the Midwest’s largest private source of philanthropic support for HIV/AIDS, a model of service coordination and Illinois’ principle advocate for people affected by HIV/AIDS. -

UAL CORPORATION UNITED AIR LINES, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): December 8, 2009 UAL CORPORATION UNITED AIR LINES, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-06033 36-2675207 Delaware 001-11355 36-2675206 (State or other Jurisdiction of (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) Incorporation) 77 W. Wacker Drive, Chicago, IL 60601 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (312) 997-8000 (Former name or former address if changed since last report.) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: o Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) o Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 8.01 Other Events. On December 8, 2009, United announced that it placed a widebody aircraft order for 25 Airbus A350 XWB aircraft and 25 Boeing 787 Dreamliner aircraft. United has future purchase rights for an additional 50 planes of each aircraft type. United expects to take delivery of the new aircraft between 2016 and 2019. -

UAL Corporation; Rule 14A-8 No-Action Letter

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549-4561 (iDIVISION OF CORPORATION FINANCE March 11,2010 Ricks P. Frazier General Counsel and Secretar (Interim) UAL Corporation P.O. Box 66919 Chicago, IL 60666 Re: UAL Corporation Incoming letter dated Februar 1, 2010 Dear Mr. Frazier: This is in response to your letter dated Februar 1,2010 concerning the shareholder proposal submitted to UAL by the Teamsters General Fund. Our response is attached to the enclosed photocopy of your correspondence. By doing this, we avoid having to recite or summarze the facts set forth in the correspondence. Copies of all of the correspondence also wil be provided to the proponent. In connection with this matter, your attention is directed to the enclosure, which sets fort a brief discussion ofthe Division's informal procedures regarding shareholder proposals. Sincerely, Heather L. Maples Senior Special Counsel Enclosures cc: C. Thomas Keegel General Secretar-Treasurer International Brotherhood of Teamsters 25 LouisianaA venue, NW Washington, DC 20001 March 11,2010 Response of the Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finânce Re: UAL Corporation Incoming letter dated Februar 1, 2010 The proposal relates to a report. There appears to be some basis for your view that UAL may exclude the proposal under rule 14a-8( t). We note your representation that the proponent does not satisfY the minimum ownership requirement for the one-year period specified in rule 14a-8(b). Accordingly, we wil not recommend enforcement action to the Commission ifUAL omits the proposal from its proxy materials in reliance on rules 14a-8(b) and 14a-8(t). -

Fortune 500 Company List

Fortune 500 Company List A • American International Group • Altria Group Inc • AmerisourceBergen Corporation • Albertson's, Inc. • Archer-Daniels-Midland Company • AT&T Corp • American Express Company • Alcoa • Abbott Laboratories • Aetna Inc. • AutoNation, Inc. • American Airlines - AMR • Amerada Hess Corporation • Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc. • American Electric Power • Apple Computer, Inc • ALLTEL Corporation • AFLAC Incorporated • Arrow Electronics, Inc. • Amgen Inc • Avnet, Inc. • Aon Corporation • Aramark Corporation • American Standard Companies Inc. • ArvinMeritor Inc • Ashland • Applied Materials, Inc • Automated Data Processing • Avon Products, Inc. • Air Products and Chemicals Inc. • Assurant Inc • Agilent Technologies Inc • Amazon.com Inc. • American Family Insurance • Autoliv • Anadarko Petroleum Corporation • AutoZone, Inc. • Asbury Automotive Group, Inc. • Allied Waste Industries, Inc. • Avery Dennison Corporation • Apache Corporation • AGCO Corporation • AK Steel Holding Corp • Ameren Corporation • Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. • Auto-Owners Insurance • Avaya Inc. • Affiliated Computer Services, Inc • American Financial Group • Advance Auto Parts Inc B • Berkshire Hathaway • Bank of America Corporation • Best Buy Co., Inc. • BellSouth Corporation • Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. • Bear Stearns Companies • Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corporation • Baxter International Inc. • BJ's Wholesale Club, Inc. • Bank of New York Co. • BB&T Corporation • Baker Hughes • Barnes & Noble Inc • Boston Scientific Corp. • Burlington Resources. -

UAL Corporation 2000 Annual Report

27988_cover_for pdf 3/9/01 11:41 AM Page 1 tion please refer to a Pantone directory, or a Draw Down of the actual color being used. Down or a Draw directory, to a Pantone tion please refer the Spot colors with CMYK values.Please note that all Digital proofs will simulate Spot color representa- accurate For UAL Corporation UAL 2000 Annual Report 2000 Annual UAL 2000 Corporation Annual Report 3% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 97% UAL #27998 batch #___ Assm by: GL Proof by:_____ QC by:_____ Date:_____ Inks/Density: C ______M ______Y ______K ______SPOT ______SPOT ______SPOT ______ K 541 8400 ❏ 2up Approval ❏ 4up Approval ❏ Waterproof ❏ CPI Standard Stock ❏ Customer Stock 27988_cover_for pdf 3/9/01 11:41 AM Page 2 tion please refer to a Pantone directory, or a Draw Down of the actual color being used. Down or a Draw directory, to a Pantone tion please refer the Spot colors with CMYK values.Please note that all Digital proofs will simulate Spot color representa- accurate For 3% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 97% UAL #27998 batch #___ Assm by: GL Proof by:_____ QC by:_____ Date:_____ Inks/Density: C ______M ______Y ______K ______SPOT ______SPOT ______SPOT ______ 8400 ❏ 2up Approval ❏ 4up Approval ❏ Waterproof ❏ CPI Standard Stock ❏ Customer Stock 27988_P1_32 3/12/01 10:29 AM Page 1 This was a tough year. Tough for employees. Customer Stock Tough for customers. ❏ Proof by:_____ QC by:_____ Date:_____ QC by:_____ Proof by:_____ PG/NS Tough for stockholders. -

2003 Catalyst Census of Women Board Directors

This is Copyrighted Material 2003 Catalyst Census of Women Board Directors A Call to Action in a New Era of Corporate Governance This is Copyrighted Material ABOUT CATALYST Catalyst is the leading research and advisory organization working to advance women in business, with offices in New York, San Jose, and Toronto.As an independent, nonprofit membership organization, Catalyst uses a solutions- oriented approach that has earned the confidence of business leaders around the world. Catalyst conducts research on all aspects of women’s career advancement and provides strategic and web-based consulting services on a global basis to help companies and firms advance women and build inclusive work environments. In addition, we honor exemplary business initiatives that promote women’s leadership with our annual Catalyst Award. Catalyst is consistently ranked No. 1 among U.S. nonprofits focused on women’s issues by The American Institute of Philanthropy. This is Copyrighted Material 2003 Catalyst Census of Women Board Directors A Call to Action in a New Era of Corporate Governance Sponsored by: The Coca-Cola Company © 2003 by CATALYST NEW YORK 120 Wall Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10005-3904; (212) 514-7600; (212) 514-8470 fax SAN JOSE 2825 North First Street, Suite 200, San Jose, CA 95134-2047; (408) 435-1300; (408) 577-0425 fax TORONTO 8 King Street East, Suite 505, Toronto, Ontario M5C 1B5; (416) 815-7600; (416) 815-7601 fax email: [email protected]; www.catalystwomen.org Unauthorized reproduction of this publication or any part thereof is prohibited by federal law. Catalyst Publication Code D30; ISBN#0-89584-183-5 This is Copyrighted Material THE CATALYST HONOR ROLL—COMPANIES WITH 25 PERCENT OR MORE WOMEN DIRECTORS: 54 COMPANIES Company Women Directors Total Directors Percent Women Directors Golden West Financial Corporation 5 9 55.6 Avon Products, Inc. -

TALX Corporation 2003 Annual Report

TALXCORPORATION 2003 ANNUAL REPORT The value is in the data. VALUE RESULTS The results are in the numbers. TALXtransforms paper-based payroll processes into efficient automated services. VALUE In fiscal 2003, TALXtransformed its business, with a sharper focus and new capabilities in payroll-data-centric services. 26% increase in payroll records to 76,400,000 RESULTS Revenues from The Work Number® services +32% The Work Number® is the nation’s pre-eminent employment database. With 26% more payroll records added in fiscal 2003, more than ever The Work Number is the first place to go for income and employment verification. By offering more value to verifiers, The Work Number generated more transactions in fiscal 2003, contributing to an increase in revenues of nearly one-third from The Work Number services. 1 TALXsimplifies payroll and unemployment compensation processes for employers. VALUE In fiscal 2003, TALXsimplified its business, with integration of staff, processes, and systems for The Work Number and the unemployment cost management businesses we acquired last year, now called UC eXpress.SM 2 7,000 clients (2/3 of the Fortune 500) RESULTS $9 million in revenues from cross-selling As the nation’s leading provider of unemployment cost management services and verification of employment and income, TALXcounts 7,000 employers among its clients. This base provides great cross-selling opportunities for the full range of TALXservices, which are all centered on a client's payroll and human resources data. In fiscal 2003, TALXsigned new contracts — for additional services to our existing clients — that will add $9 million in annual revenues. -

The Next Level JBT Corporation 2013 Annual Report Financial Highlights

The Next Level JBT Corporation 2013 Annual Report Financial Highlights Revenue Operating Income Return on (dollars in millions) (dollars in millions) Invested Capital $956 $917 $934 20.8% 18.2% $60.9 16.2% $53.2 $53.2 42% 45% 44% 6.6% 5.6% 5.7% ■ Total Revenue ■ Operating Income ■ Recurring Revenue1 ■ Operating Income % 2 011 2012 2013 2 011 2012 2013 2 011 2012 2013 (in millions, except per share and return on invested capital data) 2013 2012 % changes Operating Results Revenue $ 934.2 $ 917.3 1.8% Operating income $ 53.2 $ 60.9 -12.6% Income from continuing operations $ 34.0 $ 37.1 -8.4% Net income $ 33.1 $ 36.2 -8.6% Operating income as percent of revenue 5.7% 6.6% Per share of common stock Income from continuing operations per share, diluted $ 1.15 $ 1.26 -8.7% Other information Inbound orders $ 1,027.6 $ 971.9 5.7% Backlog $ 376.5 $ 283.1 33.0% Cash fl ows from continuing operating activities $ 63.1 $ 86.6 -27.1% Return on invested capital 2 18.2% 20.8% 1 Recurring revenue includes aftermarket parts and services, equipment leases and airport services. 2 Return on invested capital is defi ned as net income from continuing operations plus net after tax interest expense divided by average invested capital. Average invested capital is defi ned as the average of the beginning and ending (1) owners’ equity plus (2) long-term debt and less (3) cash and cash equivalents. JBT / 2013 / AR A new management team is now in place at JBT Corporation. -

Securities and Exchange Commission Schedule

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 13D (Rule 13d-101) INFORMATION TO BE INCLUDED IN STATEMENTS FILED PURSUANT TO RULE 13d-1(a) AND AMENDMENTS THERETO FILED PURSUANT TO RULE 13d-2(a) Facet Biotech Corporation (Name of Issuer) Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share Associated Preferred Stock Purchase Rights (Title of Class of Securities) 30303Q103 (CUSIP Number) Laura J. Schumacher Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary Abbott Laboratories 100 Abbott Park Road Abbott Park, Illinois 60064 (847) 937-6100 (Name, Address and Telephone Number of Person Authorized to Receive Notices and Communications) April 20, 2010 (Date of Event Which Requires Filing of this Statement) If the filing person has previously filed a statement on Schedule 13G to report the acquisition which is the subject of this Schedule 13D, and is filing this schedule because of Rule 13d-1(e), 13d-1(f) or 13d-1(g), check the following box o. Note. Schedules filed in paper format shall include a signed original and five copies of the schedule, including all exhibits. See Rule 13d-7 for other parties to whom copies are to be sent. CUSIP No. 30303Q103 1 Names of Reporting Persons Abbott Laboratories 2 Check the Appropriate Box if a Member of a Group (See Instructions) (a) o (b) x 3 SEC Use Only 4 Source of Funds (See Instructions) WC, AF 5 Check if Disclosure of Legal Proceedings Is Required Pursuant to Item 2(d) or 2(e) o 6 Citizenship or Place of Organization Illinois 7 Sole Voting Power 0 shares Number of 8 Shared Voting Power Shares 81,909,724 shares Beneficially Owned by Each Reporting 9 Sole Dispositive Power Person With 0 shares 10 Shared Dispositive Power 81,909,724 shares 11 Aggregate Amount Beneficially Owned by Each Reporting Person 81,909,724 shares 12 Check Box if the Aggregate Amount in Row (11) Excludes Certain Shares (See Instructions) o 13 Percent of Class Represented by Amount in Row (11) 100% 14 Type of Reporting Person (See Instructions) CO 2 CUSIP No. -

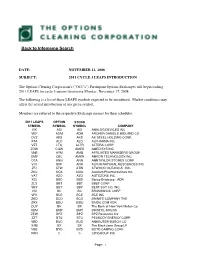

2011 Cycle 3 Leaps Introduction

TOBack: to Infomemo SearchALL CLEARING MEMBERS #25104 FROM: FRANCES KRISCHUNAS NATIONAL OPERATIONS DATE: NOVEMBER 12, 2008 SUBJECT: 2011 CYCLE 3 LEAPS INTRODUCTION The Options Clearing Corporation's ("OCC's") Participant Options Exchanges will begin trading 2011 LEAPS for cycle 3 options beginning Monday, November 17, 2008. The following is a list of those LEAPS symbols expected to be introduced. Market conditions may affect the actual introduction of any given symbol. Members are referred to the respective Exchange memos for their schedules. 2011 LEAPS OPTION STOCK SYMBOL SYMBOL SYMBOL COMPANY VIK ADI ADI ANALOG DEVICES INC VEF ADM ADM ARCHER DANIELS MIDLAND CO OVZ AKS AKS AK STEEL HOLDING CORP. XTA ALO ALO ALPHARMA INC VZT LTQ ALTR ALTERA CORP ZOW CQW AMED AMEDISYS INC VNB AYM AMG AFFILIATED MANAGERS GROUP OMY QEL AMKR AMKOR TECHNOLOGY,INC. OTA ANN ANN ANNTAYLOR STORES CORP VJV BNF ANR ALPHA NATURAL RESOURCES INC ZFJ ATW ATW ATWOOD OCEANICS , INC ZKU UQX AUXL Auxilium Pharmaceuticals Inc. VAT AZO AZO AUTOZONE INC. XSJ BBD BBD Banco Bradesco - ADR ZLS BBT BBT BB&T CORP VBY BBY BBY BEST BUY CO. INC. VXI BC BC BRUNSWICK CORP VFK BCE BCE BCE INC ZKO BCO BCO BRINK'S COMPANY THE ZRX BDU BIDU BAIDU.COM ADR OUY BK BK The Bank of New York Mellon Co VBM BMY BMY BRISTOL-MYERS ZEW BPZ BPZ BPZ Resources Inc ZZT BTU BTU PEABODY ENERGY CORP. VBD BUD BUD ANHEUSER-BUSCH CO XJM BX BX The Blackstone Group LP VBB BYD BYD BOYD GAMING CORP. VRN C C CITIGROUP INC Page: 1 2011 LEAPS OPTION STOCK SYMBOL SYMBOL SYMBOL COMPANY OYH CAG CAG CONAGRA FOODS OCJ CAH CAH CARDINAL HEALTH INC OVJ CAL CAL CONTINENTAL AIRLINES CLB ZCB CBS CBS CBS Corporation CL B ZBK CCJ CCJ CAMECO CORPORATION VCM CQL CENX CENTURY ALUMINUM COMPANY ZJZ CHL CHL China Mobile Limited ZXN CMC CMC COMMERCIAL METALS COMPANY OX CNM CME CME Group Inc ZTK QCY CMED CHINA MEDICAL TECH INC SPON ADR VBE CMI CMI CUMMINS INC.