WS Mason and the Formation of a Musical Community in Charleston, West Virgini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baccalaureate Degree Nursing Programs

STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA BOARD OF EXAMINERS FOR REGISTERED PROFESSIONAL NURSES APPROVED PRELICENSURE NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMS BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAMS ALDERSON-BROADDUS UNIVERSITY ALDERSON BROADDUS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF NURSING BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAMS 101 COLLEGE HILL DRIVE BOX 2033 PHILIPPI, WV 26416 (304) 457-6285 Fax - (304) 457-6293 DAVIS AND ELKINS COLLEGE DAVIS AND ELKINS COLLEGE BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAM 100 CAMPUS DRIVE ELKINS, WV 26241-3996 (304) 637-1314 Fax - (304)637-1218 MARSHALL UNIVERSITY MARSHALL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF HEALTH PROFESSIONS BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAM PRICHARD HALL 426 ONE JOHN MARSHALL DRIVE HUNTINGTON, WV 25755 (304) 696-6750 Fax - (304) 696-6739 SHEPHERD UNIVERSITY SHEPHERD UNIVERSITY BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAM PO BOX 5000 SHEPHERDSTOWN, WV 25443-3210 (304) 876-5341 Fax - (304) 876-5169 1 UNIVERSITY OF CHARLESTON UNIVERSITY OF CHARLESTON BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAM 2300 MACCORKLE AVENUE, SE CHARLESTON, WV 25304 (304) 357-4965 Fax - (304) 357-4965 WEST LIBERTY UNIVERSITY WEST LIBERTY UNIVERSITY BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAMS 208 UNIVERSITY DRIVE CUB #140 WEST LIBERTY, WV 26074 (304) 336-8108 Fax - (304) 336-5104 WEST VIRGINIA STATE UNIVERSITY WEST VIRGINIA STATE UNIVERSITY BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAM 106 COLE COMPLEX BARRON DRIVE INSTITUTE, WV 25112 (304) 766-5117 WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF NURSING BACCALAUREATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAMS PO BOX 9600 MORGANTOWN, WV 26506-9600 (304) 293-6521 Fax -

Recent College Admissions

SENIORS’ COLLEGE ADMISSIONS Central Piedmont Community College University of Alabama Charleston Southern University Alderson-Broaddus College A University of Charleston American University University of Chicago Anderson University Chowan University Appalachian State University Christ for the Nations Institute Aquinas College Christopher Newport University Armstrong State University The Citadel Asbury University Claflin University Auburn University Clark Atlanta University Averett University Clemson University Azusa Pacific University Coastal Carolina University Coker College Barry University College of Charleston Barton College B College of William & Mary Baylor University University of Colorado Belmont Abbey College Columbia College Belmont University Columbia College Hollywood Bemidji State University Columbia International University Berry College Connecticut School of Broadcasting Bethune-Cookman University Converse College Biola University Covenant College Birmingham-Southern College Bob Jones University Davidson College Boston University Davis & Elkins College Brevard College D University of Delaware Brewton-Parker College Denison University Bridgewater College DePaul University Broward College Dickinson College Brunswick Community College Dordt College Bucknell University Drexel University Duke University Cabarrus College of Health Sciences Caldwell Community College C East Carolina University California State University at Los Angeles Ellsworth Community College Calvin College E Elon University Campbell University Embry-Riddle -

BOARD of EXAMINERS for REGISTERED PROFESSIONAL NURSES 90 Maccorkle Avenue S.W

Sue A. Painter, DNP, RN TELEPHONE: Executive Director (304) 744-0900 FAX (304) 744-0600 email: [email protected] web address: www.wvrnboard.wv.gov STATE OF W EST VIRGINIA BOARD OF EXAMINERS FOR REGISTERED PROFESSIONAL NURSES 90 MacCorkle Avenue S.W. Suite 203 Charleston, W V 25303 STATE APPROVED NURSING PROGRAMS BACCALAUREATE NURSING PROGRAMS (4 YEARS IN LENGTH) ALDERSON-BROADDUS UNIVERSITY KIMBERLY WHITE, MSN, RN (304) 457-6285 CHAIRPERSON Fax – (304) 457-6293 ALDERSON-BROADDUS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF NURSING 101 COLLEGE HILL DRIVE BOX 2033 PHILIPPI, WV 26416 MARSHALL UNIVERSITY DENISE LANDRY, EdD, RN -CHAIR (304) - 696-6750 MARSHALL UNIVERSITY Fax – (304) 696-6739 COLLEGE OF HEALTH PROFESSIONS PRICHARD HALL 426 ONE JOHN MARSHALL DRIVE HUNTINGTON, WV 25755 SHEPHERD UNIVERSITY SHARON K. MAILEY, PhD, RN-CHAIR (304) 876-5341 SHEPHERD UNIVERSITY Fax- (304) 8 76-5169 DEPARTMENT OF NURSING EDUCATION PO BOX 5000 SHEPHERDSTOWN, WV 25443-3210 UNIVERSITY OF CHARLESTON PAMELA ALDERMAN, EdD, RN-CHAIR (304) 357-4965 DIRECTOR BSN PROGRAM Fax- (304) 357-4965 DEAN OF HEALTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF CHARLESTON 2300 MACCORKLE AVENUE, SE CHARLESTON, WV 25304 WEST LIBERTY UNIVERSITY ROSE KUTLENIOS, PhD, RN, DIRECTOR, (304) 336-8108 WEST LIBERTY UNIVERSITY Fax- (304) 336-5104 NURSING PROGRAM 208 UNIVERSITY DRIVE CUB #140 WEST LIBERTY, WV 26074 WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY TARA HULSEY, PhD, RN, CNE, FAAN, DEAN SCHOOL OF NURSING SCHOOL OF NURSING (304) 293-6521 WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY Fax – (304) 293-6826 PO BOX 9600 MORGANTOWN, WV 26506-9600 WEST VIRGINIA WESLEYAN COLLEGE TINA STRAIGHT, MSN, RN, (304) 473-8224 CHAIR, BSN PROGRAM Fax- (304) 473-8435 WEST VIRGINIA WESLEYAN COLLEGE SCHOOL OF NURSING 59 COLLEGE AVENUE BUCKHANNON, WV 26201 WHEELING JESUIT UNIVERSITY MARYANNE CAPP, DNP, RN (304) 243-2227 CHAIR DEPARTMENT OF NURSING Fax – (304) 243-2243 WHEELING JESUIT UNIVERSITY 316 WASHINGTON AVENUE WHEELING, WV 26003-6295 ASSOCIATE DEGREE NURSING PROGRAMS (2 YEARS IN LENGTH) BLUEFIELD STATE COLLEGE SANDRA M. -

Fairmont State University School of Nursing

FAIRMONT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF NURSING ASSOCIATE OF SCIENCE NURSING PROGRAM SELF-STUDY REPORT 2018 ACCREDITATION COMMISSION FOR EDUCATION IN NURSING, INC. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.1: GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................................... 5 1.2 ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 STANDARD 1 ............................................................................................................................................ 17 1.1 ........................................................................................................................................................... 17 1.2 ........................................................................................................................................................... 21 1.3 ........................................................................................................................................................... 22 1.4 ........................................................................................................................................................... 24 1.5 .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Statistical Profile of Higher Education in West Virginia, 1992-93. INSTITUTION West Virginia State Coll

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 900 HE 026 634 AUTHOR Reed, Jeannie, Ed. TITLE Statistical Profile of Higher Education in West Virginia, 1992-93. INSTITUTION West Virginia State Coll. and University Systems, Charleston. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 205p. PUB TYPE Statistical Data (110) Reports General (140) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College Faculty; College Students; *Compehsation (Remuneration); *Degrees (Academic); *Educational Finance; *Enrollment; Expenditures; Higher Education; Income; *Private Colleges; *Public Colleges; School Funds; State Universities; Statistical Data; Student Characteristics; Teacher Characteristics; Teacher Salaries; Trend Analysis IDENTIFIERS *West Virginia ABSTRACT This annual publication of the West Virginia State College and University Systems provides information related to enrollment, degrees conferred, faculty, and finances of the 16 public institutions of higher education in West Virginia. It also includes selected statistics for the 10 independent colleges and universities. Data tables comprise the bulk of the report and are listed within four chapters. The first chapter covers enrollment statistics that summarize enrollment data for the three enrollment periods and various combinations of data on enrollment, course taxonomy, student level, and demographic factors. Five and 10-year trends are also identified. The second chapter presents analyses of the degrees conferred and the teacher certifications awarded during the 1991-92 academic year by the public and independent institutions of higher education in the State. The next chapter presents faculty characteristics and average salary figures at each West Virginia public institution of higher education by highest degree and faculty rank. The final chapter presents fiscal data including current operating and capital revenue and expenditures and student fees. (GLR) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

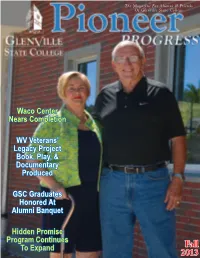

Pioneer Progress

The Magazine For Alumni & Friends Of Glenville State College Waco Center Nears Completion WV Veterans’ Legacy Project Book, Play, & Documentary Produced GSC Graduates Honored At Alumni Banquet Hidden Promise Program Continues Fall To Expand 2013 From Pete and Betsy Greetings to our Alumni and Supporters Betsy and I are extremely pleased to be writing another letter to you as we share our second issue of Pioneer Progress. Our inaugural issue in the fall of 2012 resulted in an abundance of verbal and written applause from many members of our extended Pioneer family. Therefore, we are proud to bring the fall 2013 issue to you as we showcase what our school has become because of people like you. This magazine contains snapshots and stories of our many successes that continue to take place on our campus and in the lives of our alumni and friends of Glenville State College. As you read the stories and photo captions, we hope you enjoy updates on news that we first brought to you a year ago. The beautiful Waco Center is taking shape on Mineral Road and will be completed by the first of the year to serve the next chapters of our athletic program and a multitude of services that we provide to our community, the region, and the state. We have included updates about our many successful initiatives including the Hidden Promise Scholars Program and the West Virginia Veterans’ Legacy Project. We can’t help the pride we feel as we read about the many positive and inspirational stories showcasing our generous, hardworking, and talented faculty, staff, students, alumni, and donors. -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

2020-2021 Academic Catalog

University of Charleston 2020-2021 Academic Catalog http://www.ucwv.edu The Mission of the University of Charleston is to educate each student for a life of productive work, enlightened living, and community involvement. Accredited by the Higher Learning Commission https://www.hlcommission.org/ 1-800-621-7440 Regional Accreditation: Higher Learning Commission (HLC) Specialized Accreditations Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Council for the Accreditation of Education (ACOTE) Educator Preparation (CAEP) Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Council for Interior Design Accreditation (ACPE) (CIDA) Joint Review Committee on Accreditation Review Commission on Education for Education in Radiologic the Physician Assistant, Inc. (ARC-PA) Technology (JCERT) (AS and BS) Continuing (Charleston) Joint Review Committee on Education in American Health Systems Pharmacists (ASHP) Diagnostic Medical Sonography (JRC- Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, Inc. DMS) (Registered Program) Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN) West Virginia State Board for Registered Professional Nurses (ADN and BSN) Memberships Accreditation Council of Business Schools and Mountain East Conference (MEC) Programs (ACBSP) [Candidate for Accreditation] National Association of Colleges and The American Council on Education (ACE) Employers (NACE) American Association of Colleges for Teacher National Association for Developmental Education (AACTE) Education (NADE) American Association of Colleges of Nursing National Association of -

New Members of the Class of 2024

New Members of the Class of 2024 NAMES HOMETOWN/COUNTY UNDERGRADUATE/GRADUATE COLLEGES Karim A. Abdelgaber Milton (Cabell) Marshall University Myshak S. Abdi Martinsburg (Berkeley) Hampton-Sydney College (VA) - BS Virginia Commonwealth University - MS Alex J. Ashley Walton (Roane) Marshall University Tyler D. Bayliss Hurricane (Putnam) West Virginia University Mackenzie J. Bergeron Huntington (Cabell) Alderson Broaddus University - BS & MS Seth R. Bergeron Huntington (Cabell) Alderson Broaddus University - BS & MS Heba Boustany Charleston (Kanawha) University of Kentucky Caroline B. Briggs Ashland, KY (Greenup) Transylvania University (KY) Tristan J. Burgess Huntington (Wayne) Transylvania University (KY) Taylor M. Burke Barboursville (Cabell) Marshall University Caleb A. Clark Milton (Cabell) Marshall University Lauren B. Clower Cross Lanes (Kanawha) West Virginia Wesleyan College - BS Marshall University - MS Ella K. Cooper Milton (Cabell) Marshall University Sydney R. Dangott Turtle Creek (Boone) West Virginia University Zoha Durrani Princeton (Mercer) Concord University Jeremy T. Eckels Morgantown (Monongalia) West Virginia University Morgan B. Elmore Princeton (Mercer) Concord University Wylie M. Faw, V Charleston (Kanawha) West Virginia State University Andrew S. Ferguson Winfield (Putnam) Marshall University – BS & MS Faith E. Ferguson Winfield (Putnam) Marshall University Kassandra A. Flores Akron, OH (Summit) Western Carolina University (NC) – BA Marshall University – MS Chase F. Gillispie Ona (Cabell) Marshall University John C. Goellner Morgantown (Monongalia) West Virginia Wesleyan College Lauren E. Hanna Washington (Wood) Marshall University Gavin Hayes Williamstown (Wood) Marshall University Juan Carlos Hernandez-Pelcastre Salem, VA (Salem City) Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Dontreyl Holsey Brandon, FL (Hillsborough) University of South Florida – BS Barry University (FL) – MS Jentre H. Hyde Parkersburg (Wood) Marshall University Landon E. -

The Relationship Between Lowell Mason and the Boston Handel and Haydn Society, 1815-1827

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 The Relationship Between Lowell Mason and the Boston Handel and Haydn Society, 1815-1827 Todd R. Jones University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9464-8358 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.133 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Todd R., "The Relationship Between Lowell Mason and the Boston Handel and Haydn Society, 1815-1827" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 83. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/83 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Musical Gazette (New York, 1854-1855)

Introduction to: Randi Trzesinski and Richard Kitson, The Musical Gazette (1854-1855) Copyright © 2007 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire international de la presse musicale (www.ripm.org) The Musical Gazette (1854-1855) The Musical Gazette [MGA] was published weekly on Saturdays in New York City by the Mason Brothers from 11 November 1854 until 5 May 1855, and comprised twenty-six weekly numbers, the first two containing sixteen pages each, the remainder eight pages each. The issues are numbered from 1 through 26 and the pages are numbered consecutively from 1 through 208. In 1851 Daniel Gregory Mason (1820-1869) and his brother Lowell Mason (1823-1885)—sons of music educator and composer Lowell Mason—united with Henry W. Law to create the Mason & Law publishing firm. Daniel Gregory and Lowell Mason, Junior established in 1853 their own firm, the Mason Brothers, publishers of secular and religious music, school textbooks, histories, English and French dictionaries and music periodicals.1 In 1854 they undertook publication of The Choral Advocate and Singing-Class Journal, and began two new musical periodicals in November of that year, The Musical Gazette (edited by Lowell Mason, Junior) and The Musical Review. After 5 May 1855 MGA was absorbed into another music journal published by the Mason Brothers, The New-York Musical Review and Choral Advocate which was then renamed The New-York Musical Review and Gazette.2 The Mason Brothers’ principal goal for MGA was publication of a journal “devoted to the higher departments of musical literature and criticism; … Musical news from all parts of the world, where music is cultivated, will be promptly and regularly given.”3 Each page of MGA is printed in a two-column format and issues are organized in three main parts. -

Faculty BOBO, LEIA (2011) Associate Professor of Nursing ABRUZZINO, DAVID (2011) A.S.N., B.S.N

Ph.D. University of Maryland College Park Faculty BOBO, LEIA (2011) Associate Professor of Nursing ABRUZZINO, DAVID (2011) A.S.N., B.S.N. Fairmont State Assistant Professor of National Security and M.S.N. Marshall University Intelligence B.A. Hamilton College BOGGESS, JENNIFER H. (2002) M.A. American Military University Professor of Art B.A., M.A., M.F.A. West Virginia University BAKER, J. ROBERT (1994) Director, Honors Program BOLYARD, JASON, P.E. (2007) Professor/Senior Level: English Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Graduate Faculty Technology A.B., M.A., Ph.D. University of Notre Dame A.S., B.S. Fairmont State College M.S. West Virginia University BAKER, RANDALL (1986) Assistant Professor of Computer Science CASSELL, MACGORINE (1992) B.S. Fairmont State College Professor of Business Administration M.S. West Virginia University B.B.A. Fort Valley State College M.P.A. Atlanta University BARRA, MOLLY (2017) Ph.D. United States International University First Year Experience Librarian B.A. University of Wyoming CHAPMAN, ABBY D. (2017) M.L.S. University of Pittsburgh Assistant Professor of Occupational Safety B.S. Fairmont State BAUR, ANDREAS (2000) M.S. West Virginia University Professor of Chemistry M.S., Ph.D. University of Regensburg CHIBA, TORU (2002) Electronic Services Librarian BAXTER, HARRY N., III (1985) B.A. Kansai University Professor of Chemistry M.A., M.L.I.S. University of Iowa B.S. Clarion University of Pennsylvania Ph.D. The Pennsylvania State University CLARK, TODD (2016) Assistant Professor of National Security & BIRCANN-BARKEY, INGRID (2014) Intelligence Assistant Professor of Spanish Director of Open Source Intelligence Exchange B.A.