Resisting the Norm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Digital Booklet

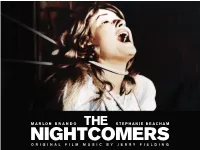

1 MAIN TITLE 2 THE SMOKING FROG 3 BEDTIME AT BLYE HOUSE 4 NEW CLOTHES FOR QUINT 5 THE CHILDREN'S HOUR 6 PAS DE DEUX 7 LIKE A CHICKEN ON A SPIT 8 ALL THAT PAIN 9 SUMMER ROWING 10 QUINT HAS A KITE 11 PUB PIANO 12 ACT TWO PRELUDE: MYLES IN THE AIR 13 UPSIDE DOWN TURTLE 14 AN ARROW FOR MRS. GROSE 15 FLORA AND MISS JESSEL 16 TEA IN THE TREE 17 THE FLOWER BATH 18 PIG STY 19 MOVING DAY 20 THE BIG SWIM 21 THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS 22 BURNING DOLLS 23 EXIT PETER QUINT, ENTER THE NEW GOVERNESS; RECAPITULATION AND POSTLUDE MUSIC COMPOSED AND CONDUCTED BY JERRY FIELDING WE DISCOVER WHAT When Marlon Brando arrived in THE NIGHTCOMERS had allegedly come HAPPENED TO THE Cambridgeshire, England, during January into being because Michael Winner wanted to of 1971, his career literally hung in the direct “an art film.” Michael Hastings, a well- GARDENER PETER QUINT balance. Deemed uninsurable, too troubled known London playwright, had constructed a and difficult to work with, the actor had run kind of “prequel” to Henry James’ famous novel, AND THE GOVERNESS out of pictures, steam, and advocates. A The Turn of the Screw, which had been filmed couple of months earlier he had informed in 1961, splendidly, as THE INNOCENTS. MARGARET JESSEL author Mario Puzo in a phone conversation In Hastings’ new story, we discover what that he was all washed up, that no one was happened to the gardener Peter Quint and going to hire him again, least of all to play the governess Margaret Jessel: specifically Don Corleone in the upcoming film version how they influenced the two evil children, of Puzo’s runaway best-seller, The Godfather. -

Iranian-Made COVID-19 Test Kits Exported to Germany

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 12 Pages Price 40,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13658 Wednesday MAY 6, 2020 Ordibehesht 17, 1399 Ramadan 12, 1441 U.S. cannot invoke Iran’s steel sections Dragan Skocic’s Slavoj Zizek snapback mechanism after production capacity contract details “Pandemic!” translated JCPOA withdrawal 2 reaches 47m tons 4 revealed 11 into Persian 12 ‘Non-oil exports to be main driver Iranian-made COVID-19 test of Iranian economy’ TEHRAN – Iranian Industry, Mining private sector, IRNA reported. and Trade Minister Reza Rahmani says Speaking in a meeting of the special non-oil export is going to be the main committee for the protection of domes- driver of the country’s economy in the tic production, Rahmani noted that the current Iranian calendar year (started country managed to export 135 million on March 19) and the ministry has it tons of non-oil commodities in the past kits exported to Germany on the agenda to activate all the coun- Iranian calendar year, despite the U.S. try’s exports capacities with a focus on sanctions. 4 See page 9 Lebanon summons German amb. over Hezbollah designation Lebanon’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a terrorist organization, rather its activities and Emigrants has summoned the Ger- have been banned in the European coun- man ambassador to the country over the try, MNA reported. The Lebanese minister designation of Hezbollah as a terrorist highlighted that Hezbollah is among the organization by the German government. -

Contemporary Films Related to Content in a Course on Death And

Contemporary Films Related to Content in a Course on Death and Grief Barbara Head, PhD, CHPN, ACSW, FPCN University of Louisville, Kent School of Social Work [email protected] Title Year Leading Actor(s) Brief Synopsis Related Course Content Amour 2012 Jean-Louis Trintignant An elderly, loving couPle struggles to Grief and loss in later life (French) Emmanuelle Riva maintain their indePendence after the Euthanasia wife suffers a Paralyzing stroke. Caregiver stress Anticipatory grief A Single Man 2009 Colin Firth A gay university Professor struggles Disenfranchised grief Julianne Moore with his grief after the sudden death of Suicide risk in bereavement his partner. Story is set in the early Historical/cultural imPacts on grief and 1960’s. loss Beyond Belief 2007 Susan Retik Two women (both Pregnant at the time) Meaning reconstruction (Documentary) Patti Quigley who lost their husbands on 911 find Resiliency meaning in their loss. Sudden, traumatic loss The Descendants 2011 George Clooney A family struggles with the imPending Children and grief Beau Bridges death and infidelity of the mother/wife Disenfranchised grief who is rendered brain dead after a Families and grief boating accident. Discontinuation of life suPPort 50/50 2011 JosePh Gordon-Levitt A young radio journalist faces treatment Counseling the seriously ill Patient Seth Rogan for a serious malignancy with a 50/50 Professional boundaries chance of survival. Grief and loss related to serious illness in a young person Social suPPort during illness Grace is Gone 2007 John Cusack The father of two young daughters Families and grief reacts to the news of the death of his Sudden, traumatic loss wife who was killed during a tour of duty Stages and tasks of grieving in Iraq. -

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Lost! The Social Psychology of Missing Possessions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1rn7b11p Author Berry, Brandon Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Lost! The Social Psychology of Missing Possessions A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Brandon Lee Berry 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Lost! The Social Psychology of Missing Possessions by Brandon Lee Berry Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Jack Katz, Chair For most, the loss of a material possession is an infrequent occurrence usually prevented through a variety of vaguely noticed practices and routines. For the sociologist, the occasion offers a natural experiment in how individuals deal with a sudden threat to the order, expectations, and material scaffolding sustaining their usual way of life. Drawing on 600 naturally-occurring cases of loss collected through observations around lost and found booths and counters, interviews with individuals recruited through lost and found websites, and guided journaling by college undergraduates about their everyday misplacements, this dissertation explores the social impact of a missing possession. Tracing losses from the moment of their discovery, I show how losing parties must carve out space from their ongoing biographies if a loss is to gain foothold as a social matter. In taking up the theme of ‘a loss’ as a matter to resolve, individuals will act to ensure that their immediate activities will go on as planned, that they will maintain untroubled ii relations with others, or that they will feel “complete.” Yet a central paradox is that the object’s loss may disturb them even while they concede its dispensability. -

![[Michael] Winner Luc Chaput](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6245/michael-winner-luc-chaput-206245.webp)

[Michael] Winner Luc Chaput

Document generated on 09/30/2021 3:14 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma [Gerry] Anderson ... [Michael] Winner Luc Chaput Number 283, March–April 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/68696ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Chaput, L. (2013). [Gerry] Anderson ... [Michael] Winner. Séquences, (283), 20–21. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 20 PANORAMIQUE | Salut l'artiste [GERRY] ANDERSON ... [MICHAEL] WINNER Gerry Anderson | 1929-2012 photographie, et le mari de la comédienne Stefan Kudelski | 1929-2013 Né Gerald Alexander Abrahams, réalisa- Luce Guilbeault. Ingénieur suisse d’origine polonaise, inven- teur et producteur britannique qui, avec teur du magnétophone Nagra (il enregistrera son épouse Sylvia Thamm, créa la télésé- Harry Carey, Jr. | 1921-2012 en polonais) et de ses multiples versions rie culte Thunderbirds (Les Sentinelles de l’air). Fils d’un acteur qui était un grand ami pour lequel il reçut quatre Oscars et la mé- de John Ford, il prit part à plus de cent daille d’honneur John Grierson de la SMPTE. -

Support for Begins to Un

The weather ■it.'-;. ITT ' ' ’ Sunny today with high near 70. In- creaiing cioudineu tonight with low SO SO. Tueiday variable cloudiness with CIWU chance ot a few showers. High in 70s. Cbahce of rain 20% tonight, 30% Tuesday. National weather forecast map on Page 7-B. FRia>:i nrr6tN.< Support for begins to un WASHINGTON (UPI) - Decision facing the committee and explainiaf a i week in the Bert Lance controversy his dealings. began t^ a y with political support for "I know that Mr. Lance hat not the White House budget director un made any such decision,” Clifford raveling as he prepared for his day in told the Washington Star. "He fecit the witness chair. he has committed no illegality and, Supporters of the former Atlanta in his opinion, no impropriety ... I banker asked only that Lance be believe it is absolutely incorrect that given a chance to answer the charges in public. 'The Senate Governmental Affairs Committee scheduled fresh Balloonil testimony from a series of govern ment officials, culminating ’Thursday with Lance’s own appearance. Carter plans a news conference Wednesday, the day before Lance call for testifies. Questions of Comptroller of the REYKJAVIK, Iceland (UPI) - Currency John Heimann were likely Two Albuquerque, N.M., men trying Army-Navy Club has family picnic to center on a newly released Inter to become the first to fly the Atlantic in a balloon, ran low on fuel today Members and families of the Army-Navy Club and Auxiliary enjoy picnicking and play nal Revenue Service report detailing efforts by Lance to conceal financial after more than 60 hours aloft and Sunday at the group’s 18th annual family picnic, at Globe Hollow. -

Radiolovefest

BAM 2017 Winter/Spring Season #RadioLoveFest Brooklyn Academy of Music New York Public Radio* Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board Cynthia King Vance, Chair, Board of Trustees William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board John S. Rose, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Katy Clark, President Susan Rebell Solomon, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Mayo Stuntz, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Laura R. Walker, President & CEO *As of February 1, 2017 BAM and WNYC present RadioLoveFest Produced by BAM and WNYC February 7—11 LIVE PERFORMANCES Ira Glass, Monica Bill Barnes & Anna Bass: Three Acts, Two Dancers, One Radio Host: All the Things We Couldn’t Do on the Road Feb 7, 8pm; Feb 8, 7pm & 9:30pm, HT The Moth at BAM—Reckless: Stories of Falling Hard and Fast, Feb 9, 7:30pm, HT Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me®, National Public Radio, Feb 9, 7:30pm, OH Jon Favreau, Jon Lovett, and Tommy Vietor, Feb 10, 7:30pm, HT Snap Judgment LIVE!, Feb 10, 7:30pm, OH Bullseye Comedy Night, Feb 11, 7:30pm, HT BAMCAFÉ LIVE Curated by Terrance McKnight Braxton Cook, Feb 10, 9:30pm, BC, free Gerardo Contino y Los Habaneros, Feb 11, 9pm, BC, free Season Sponsor: Leadership support provided by The Joseph S. and Diane H. Steinberg Charitable Trust. Delta Air Lines is the Official Airline of RadioLoveFest. Audible is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. VENUE KEY BC=BAMcafé Forest City Ratner Companies is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. BRC=BAM Rose Cinemas Williams is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. -

April 2018 82

82 APRIL 2018 APRIL 2018 83 “ A bird-brained movie to cheer the hearts of the far right wing,” sneered Vincent Canby in the 25 July 1974 edition of The New York Times. The movie he was reviewing was Death Wish, a new crime thriller directed by Michael Winner, in which Winner’s frequent cohort, Charles Bronson, embarked on a vigilante crusade in New York, incited by the murder of his wife and rape of his daughter. And Canby wasn’t alone in his disdain. Variety called it “a poisonous incitement to do-it- yourself law enforcement”. Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times thought its message was “scary”. But Death Wish was unstoppable. In the US, the $3 million movie grossed $22 million and was followed by four sequels, two now infamous for their extreme sexual violence. The fnal one, 1994’s Death Wish V: The Face Of Death, was Bronson’s fnal big-screen role. Even without him, the series refused to die, as the fact there’s a new remake incoming attests. It has, however, taken time to arrive. In 2006, it was announced that Sylvester Stallone would star in and direct a new Death Wish; when he left the project, Joe Carnahan (The A-Team) took over. That version languished in development hell too, and is only now circling the roles of Benjamin and police making it to the screen, directed by Eli DEATHWISH (1974) chief Frank Ochoa. But time went on, Roth from Carnahan’s script and starring It could all have been very different. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

Liste Des Chaines /Filmes/Vods/Series

Liste des Chaines /Filmes/VODs/Series www.laboutiqueiptv.com Colonne1 Tunisia 1 Tunisia 2 Tunisia Nat 3 Elhiwar Ettounsi ATTESSIA Nessma Hannibal Telvza Tv Al Janoubia Tunisna MTunisia Sahel TV Al Mustakillah Zitouna Al Insen Carthage TV AR-MECCA CANAL ALGERIE ENTV Algeria 3 AR-Algerie-Tamazight-tv4 TV5 Samira Echorouk Echourouk News Echorouk Benna Ennahar Elheddaf Dzair Dzair News Numidia News El Djazairia 1 EL BILAD Beur Fadjr Bahia Berbere Al Magharibia 1 AlaoulaInterHD ALAoulaInter AR-AlAoula-Layoune Liste des Chaines /Filmes/VODs/Series www.laboutiqueiptv.com 2M Maroc Arryadia AR-Arrabiaa AlMaghrebia Assadissa Maroc Tamazight AR-Medi-1_TV AR-MBC1_HD AR-MBC_1 AR-MBC_2 AR-MBC2_HD AR-MBC_4 AR-MBC4_HD AR-MBC-MAX AR-MBC_MAX-HD AR-MBC-Action AR-MBC_Action-HD AR-MBC-DRAMA AR-MBC_Drama-HD AR-MBC_MASR AR-MBC-masr2 AR-MBC_Bollywood-HD AR-MBC_Bollywood AR-Rotana_Cinema-HD AR-Rotana-Cinema-EGY AR-Rotana-Cinema-KSA AR-Rotana_Aflam AR-Rotana_Masria-HD AR-Rotana-Masriya AR-Rotana-Clip AR-Rotana_Music-HD AR-Rotana-Music AR-Rotana-Khalijiya HD AR-Rotana-Khalijiya AR-Rotana_Classic-HD AR-Rotana-Classic AR-ART_Aflam_1 AR-ART_Aflam-2 AR-ART_Cinema AR-ART_Hekayat-1 AR-ART_Hekayat-2 AR-BeIn_Movies1_HD AR-BeIn_Movies2_HD AR-BeIn_Movies3_HD AR-BeIn_Movies4_HD Ar-Bein-Gourmet Ar-Bein-Junior Liste des Chaines /Filmes/VODs/Series www.laboutiqueiptv.com Ar-BeinDrama AR-StarCinema-1 AR-StarCinema-2 AR-Toktok_Cima AR-Cima AR-AL-SHASHA-CINEMA AR-4G-AFLAM AR-4G-CIMA AR-4G-CLASSIC AR-4G-DRAMA AR-4G-FILM AR-CINEMA-1 AR-CINEMA-2 AR-CIMA-TUBE AR-CINEMA-TUBE AR-Darbaka-Aflam -

Scorses by Ebert

Scorsese by Ebert other books by An Illini Century roger ebert A Kiss Is Still a Kiss Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook Behind the Phantom’s Mask Roger Ebert’s Little Movie Glossary Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion annually 1986–1993 Roger Ebert’s Video Companion annually 1994–1998 Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook annually 1999– Questions for the Movie Answer Man Roger Ebert’s Book of Film: An Anthology Ebert’s Bigger Little Movie Glossary I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie The Great Movies The Great Movies II Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert Your Movie Sucks Roger Ebert’s Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007 With Daniel Curley The Perfect London Walk With Gene Siskel The Future of the Movies: Interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas DVD Commentary Tracks Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Casablanca Citizen Kane Crumb Dark City Floating Weeds Roger Ebert Scorsese by Ebert foreword by Martin Scorsese the university of chicago press Chicago and London Roger Ebert is the Pulitzer The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Prize–winning film critic of the Chicago The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London Sun-Times. Starting in 1975, he cohosted © 2008 by The Ebert Company, Ltd. a long-running weekly movie-review Foreword © 2008 by The University of Chicago Press program on television, first with Gene All rights reserved. Published 2008 Siskel and then with Richard Roeper. He Printed in the United States of America is the author of numerous books on film, including The Great Movies, The Great 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 Movies II, and Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, the last published by the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18202-5 (cloth) University of Chicago Press. -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number.