Forest and Common Land Acquisition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masters Degree Theses List.Xlsx

Master of Environmental Planning Management Thesis List S.No TH.No Author Dissertation Title Year Dept Name of the Supervisor 1 TH 256 Anitha Vultela Impact Assessment of Irregation Dam on The Settlements: 2014-15 MEPM Dr. Natraj Kranthi , 2130300001 A Case Study of Pulchintala Dam in Andhra Pradesh Associate Professor, SPAV 2 TH 257 babita Urban Green as Carbon Sink for Industrial Emission: 2014-15 MEPM Mr. Ayon Kuamr Tarafdar, 2130300002 A Case of Chandigarh U.T Associate Professor, SPAV 3 TH 258 Pallavi Meruga Strengthening The Performance of Domestic Water Supply Services: A case 2014-15 MEPM Mr. Maqbool Ahmed, 2130300004 Of Tirupati Cuity Assistant Professor, SPAV 4 TH 259 Ch.Stalin Rajesh Assessment of Socieoconomic Factors That Affect Domestic Solid Waste 2014-15 MEPM Ms.Aparna Soni, 2130300005 Generation And Composition Assistant Professor, SPAV 5 TH 260 Vamsi Deepak TSV Strategies for Ecotourism Development in Krishna District, 2014-15 MEPM Dr.N.Sridharan, 2130300006 Andhra Pradesh Professor, SPAV 6 TH 261 Mohammad Waseem Planning for Sustainable Water Management Practices 2014-15 MEPM Dr.N.Sridharan, 2130300007 in an Industrial Area Professor, SPAV 7 TH 262 A.Priya Changing Land Use And Its Impact on Ground Water Resource: 2014-15 MEPM Mr. Ayon Kuamr Tarafdar, 2130300008 A Case of Guntur City Associate Professor, SPAV S.No TH.No Author Dissertation Title Year Dept Name of the Supervisor 1 TH 288 Amanpreet Kaur Decarbonisation of Urban Transport: Amritsar 2015-16 MEPM Mr. Ayon Kuamr Tarafdar, 2140300009 Associate Professor, SPAV 2 TH 289 Bachala Poojitha Strategizing the Change in Energy Consumption for Medium Consumption- A 2015-16 MEPM Dr. -

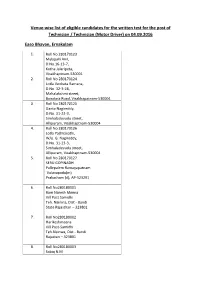

(Motor Driver) on 04.09.2016

Venue-wise list of eligible candidates for the written test for the post of Technician / Technician (Motor Driver) on 04.09.2016 Easo Bhavan, Ernakulam 1. Roll No 280170123 Mylapalli Anil, D.No.16-13-7, Kotha Jalaripeta, Visakhaptnam-530001 2. Roll No 280170124 Lotla Venkata Ramana, D.No. 32-3-28, Mahalakshmi street, Bowdara Road, Visakhapatnam-530004 3. Roll No 280170125 Ganta Nagireddy, D.No. 31-23-3, Simhaladevudu street, Allipuram, Visakhaptnam-530004 4. Roll No 280170126 Lotla Padmavathi, W/o. G. Nagireddy, D.No. 31-23-3, Simhaladevudu street, Allipuram, Visakhaptnam-530004 5. Roll No 280170127 SERU GOPINADH Pallepalem Ramayapatnam Vulavapadu(m) Prakasham (d), AP-523291 6. Roll No280180001 Ram Naresh Meena Vill Post Samidhi Teh. Nainina, Dist - Bundi State Rajasthan – 323801 7. Roll No280180002 Harikeshmeena Vill Post-Samidhi Teh.Nainwa, Dist - Bundi Rajastan – 323801 8. Roll No280180003 Sabiq N.M Noor Mahal Kavaratti, Lakshadweep 682555 9. Roll No280180004 K Pau Biak Lun Zenhanglamka, Old Bazar Lt. Street, CCPur, P.O. P.S. Manipur State -795128 10. Roll No280180005 Athira T.G. Thevarkuzhiyil (H) Pazhayarikandom P.O. Idukki – 685606 11. Roll No280180006 P Sree Ram Naik S/o P. Govinda Naik Pedapally (V)Puttapathy Anantapur- 517325 12. Roll No280180007 Amulya Toppo Kokkar Tunki Toli P.O. Bariatu Dist - Ranchi Jharkhand – 834009 13. Roll No280180008 Prakash Kumar A-1/321 Madhu Vihar Uttam Nagar Newdelhi – 110059 14. Roll No280180009 Rajesh Kumar Meena VPO Barwa Tehsil Bassi Dist Jaipur Rajasthan – 303305 15. Roll No280180010 G Jayaraj Kumar Shivalayam Nivas Mannipady Top P.O. Ramdas Nagar Kasargod 671124 16. Roll No280180011 Naseefahsan B Beathudeen (H) Agatti Island Lakshasweep 17. -

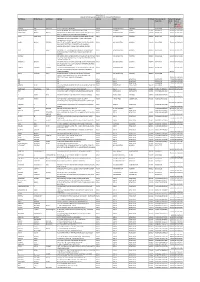

10. Tranche 2-2010-11-IDFB BOND B1 Final

IDFC Infrastructure Bonds- Unpaid/Unclaimed Interest- Tranche 2- Series 1- 2010-11 Father's/ Father's/ Father's/ Proposed Date of husband's First husband's Middle husband's Last Amount transfer to IEPF (DD- Sr. No First name Middle Name Last Name Name Name Name Address Country State District PIN code Folio Number Investment Type Due (Rs.) MON-YYYY) J KESHAVA MURTHY NA RANDANKD KANDFJLAJL INDIA PUNJAB CHANDIGARH IDB0158720 Amount for unclaimed and 1600.00 20-FEB-2019 1 unpaid dividend VIJAYESH RANA NA VIJAESH RANA H.NO:3520 CHANDIGARH INDIA PUNJAB CHANDIGARH IDB0158722 Amount for unclaimed and 1600.00 20-FEB-2019 2 unpaid dividend C THAMIZH ARASAN NA 3/218, VICTORY STREET CHEYYAR INDIA PUNJAB CHANDIGARH IDB0158727 Amount for unclaimed and 1600.00 20-FEB-2019 3 unpaid dividend DIDAR SINGH NA S/O JAIR NAIL SINGH VILL P.O BHARO INDIA PUNJAB CHANDIGARH IDB0158733 Amount for unclaimed and 1600.00 20-FEB-2019 4 MAZARA S.B.S NAGAR unpaid dividend DR HARI SHANKAR NA VIKAS BHAWAN LALITPUR LALITPUR INDIA PUNJAB CHANDIGARH IDB0158735 Amount for unclaimed and 1600.00 20-FEB-2019 5 BABELEY unpaid dividend PURSHOTTA LAL KEDIA NA HNO 56 VILLAGE MAHAVIR PRABAD INDIA RAJASTHAN BHALSALPUR IDB0158738 Amount for unclaimed and 1600.00 20-FEB-2019 M DWIRED PO SUJAGANJ DIST unpaid dividend 6 BHALSALPUR MILAN LUTHRA NA HNO 56 VILLAGE MAHAVIR PRABAD INDIA RAJASTHAN BHALSALPUR IDB0158740 Amount for unclaimed and 1600.00 20-FEB-2019 DWIRED PO SUJAGANJ DIST unpaid dividend 7 BHALSALPUR DUSHYANT KUMAR NA C-773, DDA FLATS LIG FLATS OF LONI INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI IDB0158743 -

Hydrogeological Investigation in Salem District

HYDROGEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION IN SALEM DISTRICT A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF TECHNOLOGY in GEOPHYSICAL TECHNOLOGY YOGANDRE SINGH DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE ROORKEE - 247 667 (INDIA) JUNE, 2012 CANDIDATE'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that the work which is presented in this dissertation entitled "ilydrogeological Investigation in Salem District" in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of degree of Master of Technology in "Geophysical Technology" with the specialization in Exploration Geophysics submitted in Department of Earth Sciences, IIT Roorkee. Roorkee, is an authentic record of my own work carried out during the period from July 201 1 to June 2012 under the supervision of Prof. Sri Niwas, Department of Earth Sciences, 111 Roorkee. Roorkee. l'he matter embodied in this thesis has not been submitted by me for award of any other degree. Date: ld -0 6-2o1~ Place: Roorkee Yogandre Singh Phis is certified that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. (Prof. Sri Niwas) Department of Earth Sciences IIT Roorkee Roorkee-247667 CERTIFICATE I. Yogandre Singh, hereby solemnly declare that the dissertation entitled "Hydrogeological Investigation in Salem District" being submitted by me towards partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of "Master of Technology in Geophysical Technology". Degree is a record of my own work and that I have not copied the work of any other person(s) including published literature and material from any web site. Where ever the work of other person(s) has been used, it has been duly acknowledged and quoted with proper reference to the original work. -

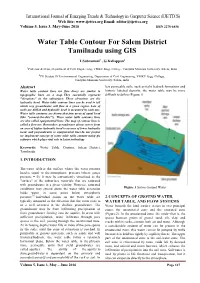

Water Table Contour for Salem District Tamilnadu Using GIS

International Journal of Emerging Trends & Technology in Computer Science (IJETTCS) Web Site: www.ijettcs.org Email: [email protected] Volume 5, Issue 3, May-June 2016 ISSN 2278-6856 Water Table Contour For Salem District Tamilnadu using GIS T.Subramani1 , G.Kaliappan2 1Professor & Dean, Department of Civil Engineering, VMKV Engg. College, Vinayaka Missions University, Salem, India 2PG Student Of Environmental Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, VMKV Engg. College, Vinayaka Missions University, Salem, India Abstract less permeable soils, such as tight bedrock formations and Water table contour lines (or flow lines) are similar to historic lakebed deposits, the water table may be more topographic lines on a map. They essentially represent difficult to define.(Figure.1) "elevations" in the subsurface. These elevations are the hydraulic head. Water table contour lines can be used to tell which way groundwater will flow in a given region. Lots of wells are drilled and hydraulic head is measured in each one. Water table contours are drawn that join areas of equal head (like "connect-the-dots"!). These water table contours lines are also called equipotential lines. The map of contour lines is called a flow net. Remember: groundwater always moves from an area of higher hydraulic head to an area of lower hydraulic head, and perpendicular to equipotential lines.In our project we implement concept of water table table contour using gis software which plays vital role in latest technology. Keywords: Water Table, Contour, Salem District, Tamilnadu 1. INTRODUCTION The water table is the surface where the water pressure head is equal to the atmospheric pressure (where gauge pressure = 0). -

(Autonomous) Visakhapatnam Annual Report 2018 – 2019

St. Joseph’s College for Women (Autonomous), Visakhapatnam 1 ST. JOSEPH’S COLLEGE FOR WOMEN (AUTONOMOUS) VISAKHAPATNAM ANNUAL REPORT 2018 – 2019 “We cannot accept that salt should become tasteless or the light be kept hidden” (cf. Mt 5:13-16) ‘Kindle the light within to reach out’ St. Joseph’s College for Women (Autonomous), Visakhapatnam 2 INDEX Page S.No. Contents No. 3 A. Curriculum Design and Development 28 B. Value Added Certificate 30 C. List out Guest Lectures 38 D. Seminars 40 E. Dept. participation in Extension Activities 41 F.Functional MOUs with Institutions 43 I G.Deptartment Library is Maintained 44 H.Department Log Book is maintained for usage of instruments 45 I.Field Visits 48 J.Days or Weeks Observed,Celebrated in the dept. 51 K.Departmental Best Practice 59 L.Future Plans of the Department 61 M.Over all Department Analysis 66 A.Use of ICT in Teaching 80 B. Honours, Recognitions, Awards Received by Teachers 82 C. Details of M.Phil,Ph.D awarded in the dept. During the Year 2018-19 83 D. Research Papers Published during the year 2018-19 96 E.Articles Published in General Magazines, News Papers 98 II F. Books, Chapters Authored in 2018-19 101 G. Details of Paper Presentation at Sem.,Conf.,WS,Symp. during 2018-19 103 H. Details of Faculty Participation (without Paper) 107 I. Research projects undertaken by the Faculty 108 K. Orientation, Refresher course, Any other training, MOOC Courses, FDP Participated during 2018-19 111 L. Details of Consultancy & Revenue Generated 112 M. Details of Faculty Serving 118 III Annual Report Criteria III Consolidated St. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid Interim dividend for FY 2010-11 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) JAGDISH DAS SHAH HUF CK 19/17 CHOWK VARANASI INDIA UTTAR PRADESH VARANASI BIO040743 150.00 03-JUN-2018 RADHESHYAM JUJU 8 A RATAN MAHAL APTS GHOD DOD ROAD SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395001 BIO054721 150.00 03-JUN-2018 DAMAYANTI BHARAT BHATIA BNP PARIBASIAS OPERATIONS AKRUTI SOFTECH PARK ROAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO001163 150.00 03-JUN-2018 NO 21 C CROSS ROAD MIDC ANDHERI E MUMBAI JYOTI SINGHANIA CO G.SUBRAHMANYAM, HEAD CAP MAR SER IDBI BANK LTD, INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO011395 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ELEMACH BLDG PLOT 82.83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI GOKUL MANOJ SEKSARIA IDBI LTD HEAD CAPITAL MARKET SERVIC CPU PLOT NO82/83 INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO017966 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 15 OPP SPECIALITY RANBAXY LABORATORI ES MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI-4000093 DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 150.00 03-JUN-2018 PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MKT SER INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 150.00 03-JUN-2018 C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 150.00 03-JUN-2018 -

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR CODE ANDAMAN and NICOBAR ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair MB

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN AND MB 23, Middle Point, Mrs. Kavitha NICOBAR Port Blair - 744101, Ravi - 03192- ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair Andaman PORT BLAIR ICIC0002144 232213/14/15 PARAMES WARA ICICI BANK LTD., RAO OPP. R. T. C. BUS KURAPATI- ANDHRA STAND, 98489 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ADILABAD.504 001 ADILABAD ICIC0000617 37305- 4-3-168/1, TNGO’S ROAD (CINEMA ROAD ), PADAM HAMEEDPURA CHAND (DWARIKA NAGAR) GUPTA OPP. SRINIVASA 08732- NURSING HOME, 230230; ANDHRA ADILABAD 504001 934788180 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD (A.P>) ADILABAD ICIC0006648 1 ICICI Bank Ltd., Plot No. 91 & 92, Mr. Ramnathpuri Scheme, Satyendra ANDHRA JAIPUR,JHOTWA Jhotwara, Jaipur - Bhatt-141- PRADESH ADILABAD RA 302012, Rajasthan JAIPUR ICIC0006759 3256155 302229057 SUSHIL RAMBAGH PALACE KUMAR JAIPUR,RAM HOTEL RAMBAGH VYAS,0141- ANDHRA BAGH PALACE CIRCLE JAIPUR 3205604,,9 PRADESH ADILABAD HOTEL 302004 JAIPUR ICIC0006778 314661382 ICICI BANK LTD., NO. 12-661, GOKUL COMPLEX, BELLAMPALLY 08736 ROAD, MANCHERIAL, 255232, ANDHRA ADILABAD DIST. 504 MANCHERIY 08736 PRADESH ADILABAD MANCHERIYAL 208 AL ICIC0000618 255234 ICICI BANK LTD., OLD GRAM PANCHAYAT, MUDHOL - RAJESH 504102, TUNGA - ANDHRA ADILABAD DIST., +91 40- PRADESH ADILABAD MUDHOL ANDHRA PRADESH MUDHOL ICIC0002045 41084285 91 9908843335 504229502 ICICI BANK LIMITED PODDUTOOR COMPLEX, D.BO.1-2- 275, (OLD NO 1-2-22 TO 26 ) OPP . BUS SHERRY DEPOT, NIRMAL, JOHN 8942- NIRMAL ADILABAD (DIST), 224213 ANDHRA ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH – ,800847763 PRADESH ADILABAD PRADESH 504106 NIRMAL ICIC0001533 2 ICICI BANK LTD, NAVEED MR. SAI RESIDENCY, RAJIV GOPAL ROAD, PATRO ANDHRA ANANTAPUR- 515001 ANANTAPU (08554) - PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTPUR ANDHRA PRADESH R ICIC0000439 645033 ICICI BANK LTD., D.NO:12/114 TO 124, PRAMEEL R.S.ROAD, OPP DEVI A P -08559- NURSING HOME, 223943, ANDHRA DHARMAVARAM.515 DHARMAVA 970301725 PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM 671 RAM ICIC0001034 4 16-337, GUTTI ROAD, GUNTAKAL-DIST. -

Annual Report 2015–16

ANNUAL REPORT 2015–16 ASHOKA TRUST FOR RESEARCH IN ECOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2015–16 Coverpage Image: Fishermen in Vembanad, Kerala continue to practice sustainable fishing. © Shaji Cherthala ASHOKA TRUST FOR RESEARCH IN ECOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT Contents 04 GOVERNING BOARD 05 ADVISORY BOARD 06 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 07 DIRECTOR’S DESK 08 RECOGNITIONS AND ACHIEVEMENTS 09 RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS 10 Centre for Environment and Development Water, Land and Society Forests and Governance Climate Change Mitigation and Development 1. Critically Endangered Sociable Lapwing Spotted 16 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation in Kutch, Gujarat. © Ovee Thorat Biodiversity Monitoring and Conservation Planning 2. Roarchestes chalazodes. © Surya Narayanan Landscapes, Livelihoods and Conservation 3. Parakeets: Blossom headed parakeets spotted at Papikonda National Park, Andhra Pradesh. Ecosystem Services and Human Wellbeing © Vikram Aditya 1 23 COMMUNITY CONSERVATION CENTRES Agasthyamalai Community Conservation Centre Vembanad Community Environmental Resource Centre Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple and the Male Mahadeshwara Community Conservation Centres 26 ATREE EASTERN HIMALAYA/NORTHEAST INDIA INITIATIVE 32 ACADEMY FOR Conservation SCIENCE 2 AND SustainaBILITY STUDIES 34 PUBlications Journal Articles Books Book Chapters 3 Popular Articles Conference Proceedings 40 OUR TEAM 42 FUNDING PARTNERS 43 FINANCIALS Governing Board Advisory Board ** Dr. K. S. Bawa mS. Pheroza J. GoDreJ * Dr. K. ViJayraGhaVaN Chairman of the Governing Board, ATREE and Founder, -

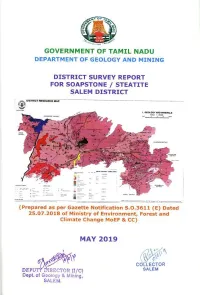

2. Overview of Mining Activity in Salem District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT SALEM DISTRICT Page Chapter Content No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Overview of Mining/ Quarrying Activity in the District 4 3. General Profile of the District 11 4. Geology and Mineral Wealth of the District 12 5. Drainage of Irrigation pattern 21 6. Land Utilisation Pattern in the District: Forest, Agricultural, 25 Horticultural, Mining etc., 7. Surface Water and Ground Water scenario of the District 28 8. Rainfall of the District and climatic condition 29 9. Details of quarrying Leases in the District 34 10. Details of Revenue and Production in last three years 34 11. Mineral Map of the District 35 12. List of Letter of Intent (LOI) Holder in the District along with 36 its validity 13. Total Mineral Reserve available in the district 36 14. Quality/Grade of Mineral available in the district 37 15. Use of Mineral 37 16. Demand and supply of the Mineral in the last three years 37 17. Mining Leases marked on the map of the district 38 18. Details of the area of where there is a cluster of the mining 40 leases 19. Details of Eco-sensitive area 40 20. Impact on the environment due to Mining activity 40 21. Remedial measures to mitigate the impact of mining on the 40 environment 22. Reclamation of the mined out area 44 23. Risk assessment & Disaster Management Plan 44 24. Details of Occupational health issue in the District 45 25. Plantation and Green belt development in respect of leases 45 already granted in the district 26. Any other information 46 Page No. -

Fluoride Were Determined for the Water Samples

“Save Water To Secure Your Future.” ASSESSMENT OF DRINKING WATER QUALITY IN METTUR AND MECHERI REGIONS OF SALEM DISTRICT, TAMILNADU WITH USING JAL – TARA WATER TESTING KIT submitted by [1] “Save Water To Secure Your Future.” ACKNOWLEDGEMENT we wish to avail this opportunity and place on record my deep sense of gratitude and a heart-felt thanks to our guide Atul Pant, founder of Timeless Life skills Limited, United Kingdom of Great Britain, for his expert guidance and shalini akka, her valuable suggestions, inspiration and invaluable insights in choosing the field of our study without whom this work would not have reached its present form.. But for the unceasing guidance, unstinted co-operation and encouragement this dissertation may not be a reality. I gratefully remember the tireless endeavor that he put forth. we extend our grateful thanks to N. Sasikala DCT, BCA, BSc, MA, B.Ed Principal of isha vidhya ramaniyam matric higher secondry school, vanavasi, salem for providing necessary laboratory facilities, timely valuable suggestion and training in the investigation conducted and for her kind support, timely help and enthusiasm rendered throughout the course of our study. We also wish to express our grateful thanks to N. JANAGI M.Sc, M.Ed, Vice Principal of isha vidhya ramaniyam matric higher secondry school, vanavasi, salem for evincing keep interest in this work. We highly indebted to Mr. BHARANIDHARAN MSc, M.Ed, isha vidhya coordinator, for their valuable guidance, constant supervision, constructive critism and constant support,in helping us to complete this dissertation work. Their unfailing encouragement, personal advice and affection will always stand in good stead in my memory.