Research Paper for a Master's Recital of Viola: Suite No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1009 by J.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

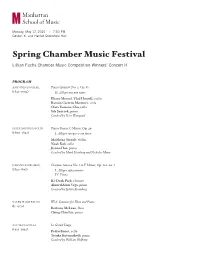

2021.5.17 Chamber Fest 2 R3

Monday, May 17, 2021 | 7:30 PM Gordon K. and Harriet Greenfield Hall Spring Chamber Music Festival Lillian Fuchs Chamber Music Competition Winners’ Concert II PROGRAM ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK Piano Quintet No. 2, Op. 81 (1841–1904) II. Allegro ma non tanto Eliane Menzel, Vlad Hontilă, violin Ramón Carrero Martínez, viola Clara Yeonsue Cho, cello Sıla Şentürk, piano Coached by Peter Winograd FELIX MENDELSSOHN Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 49 <Piano Trio No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 66?> (1809–1847) I. Allegro energico e con fuoco Maïthéna Girault, violin Noah Koh, cello Jiyoon Han, piano Coached by Mark Steinberg and Nicholas Mann JOHANNES BRAHMS Clarinet Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120, no. 1 (1833–1897) I. Allegro appassionato IV. Vivace Ki-Deok Park, clarinet Ahmed Alom Vega, piano Coached by Sylvia Rosenberg VALERIE COLEMAN Wish: Sonatine for Flute and Piano (b. 1970) Bethany McLean, flute Ching Chia Lin, piano ASTOR PIAZOLLA Le Grand Tango (1921–1992) Pedro Bonet, cello Tatuka Kutsnashvili, piano Coached by William Wol!am Students in this performance are supported by the Robert Mann Endowed Scholarship for Violin and Chamber Studies, the Samuel and Mitzi Newhouse Scholarship, the Flavio Varani Scholarship in Piano, the Viola B. Marcus Memorial Scholarship, the Rachmael Weinstock Endowed Scholarship in Violin. We are grateful to the generous donors who made these scholarships possible. For information on establishing a named scholarship at Manhattan School of Music, please contact Susan Madden, Vice President for Advancement, at 917-493-4115 or [email protected]. ABOUT LILLIAN FUCHS Hailed by Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times in 1962 as “one of the best string players in America,” Lillian Fuchs (1902–1995) joined the chamber music and viola faculties at Manhattan School of Music in 1962, where she remained for almost 30 years. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE the Gypsy Violin A

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Gypsy Violin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Music, Performance By Eun Ah Choi December 2019 The thesis of Eun Ah Choi is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Liviu Marinesqu Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Ming Tsu Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Lorenz Gamma, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Table of Contents Signature Page…………………………………………………………………………………….ii List of Examples……………………………………………………………………………...…..iv Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………....v Chapter 1: Introduction.……………..……………………………………………………….……1 Chapter 2: The Establishment of the Gypsy Violin.……………………….……………………...3 Chapter 3: Bela Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances [1915].………….…….……………………….8 Chapter 4: Vittorio Monti’s Csádás [1904]….…………………………………..………………18 Chapter 5: Conclusion …………..……………...……………………………………………….24 Works Cited.…………….……………………………………………………………………….26 California State University, Northridge iii List of Examples 1 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement I: mm. 1-13……………………………………..9 2 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement II: mm. 1-16…………………………...………10 3 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement III …………………………………..…………12 4 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement IV …………………………………..…………14 5 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement V: mm. 5-16…………………………………...16 6 Monti’s Csárdás, m. 5………………………………………………..………………......19 7 Monti’s Csardas, mm. 6-9…………………………………………..…………………...19 8 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 14-16.…………………………………….……………………...20 9 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 20-21.………………………………….……………………..….20 10 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 22-37………………….…………………………………………21 11 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 38-53…………………….………………………………………22 12 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 70-85…………………….………………………………………23 iv Abstract The Gypsy violin By Eun Ah Choi Master of Music in Music, Performance The origins of the Gypsies are not exactly known, and they lived a nomadic lifestyle for centuries, embracing many cultures, including music. -

Lillian Fuchs: Violist, Teacher and Composer

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Lillian Fuchs: violist, teacher and composer; musical and pedagogical aspects of the 16 Fantasy études for viola Teodora Dimova Peeva Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Peeva, Teodora Dimova, "Lillian Fuchs: violist, teacher and composer; musical and pedagogical aspects of the 16 Fantasy études for viola" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3589 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LILLIAN FUCHS: VIOLIST, TEACHER, AND COMPOSER; MUSICAL AND PEDAGOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE 16 FANTASY ÉTUDES FOR VIOLA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Teodora Peeva B.M., University of California, 2003 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 May, 2011 TO THE MEMORY OF MY PARENTS ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To David and the entire Weill family, for your unflagging encouragement and support. To Ms. Lori Patterson, for selflessly sharing your wisdom with me and for allowing me the pleasure of knowing you. My deepest gratitude goes to the members of my doctoral committee, for your contribution of time and knowledge in assisting with the completion of this monograph and for your willingness to serve. -

CCMA Coleman Competition (1947-2015)

THE COLEMAN COMPETITION The Coleman Board of Directors on April 8, 1946 approved a Los Angeles City College. Three winning groups performed at motion from the executive committee that Coleman should launch the Winners Concert. Alice Coleman Batchelder served as one of a contest for young ensemble players “for the purpose of fostering the judges of the inaugural competition, and wrote in the program: interest in chamber music playing among the young musicians of “The results of our first chamber music Southern California.” Mrs. William Arthur Clark, the chair of the competition have so far exceeded our most inaugural competition, noted that “So far as we are aware, this is sanguine plans that there seems little doubt the first effort that has been made in this country to stimulate, that we will make it an annual event each through public competition, small ensemble chamber music season. When we think that over fifty performance by young people.” players participated in the competition, that Notices for the First Annual Chamber Music Competition went out the groups to which they belonged came to local newspapers in October, announcing that it would be held from widely scattered areas of Southern in Culbertson Hall on the Caltech campus on April 19, 1947. A California and that each ensemble Winners Concert would take place on May 11 at the Pasadena participating gave untold hours to rehearsal Playhouse as part of Pasadena’s Twelfth Annual Spring Music we realize what a wonderful stimulus to Festival sponsored by the Civic Music Association, the Board of chamber music performance and interest it Education, and the Pasadena City Board of Directors. -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 11 No. 3, 1995

RBP IS pleased to announce a unique new line of exceptional arrangements for viola, transcribed and edited by ROBERT BRIDGES This collection has been thoughtfully crafted to fully exploit the special strengths and sonorities of the viola We're confident these arrangements will be ettecnve and useful additions to any violist's recital library 1001 Biber Passacaglia (violin) 5 5 75 1002 Beethoven Sonata op 5 #2 (cello) 5 9 25 1003 Debussy Rhapsody (saxophone) . 514 25 1004 Franck Sonata (violin) 510 75 1005 Telemann Solo Suite (gamba) 5 6.75 1006 Stravinsky Suite for Via and plano 52800 1007 Prokofiev "Cinderella" Suite for Viola and Harp 525 00 Include 51.50/item for shipping and handling "lo order, send your check or money order to: send for RBP Music Publishers our FREE 2615 Waugh r». Suite 198 catalogue! Houston, Texas 77006 ~ I 13 The end of the transition (Ex. 2) has a distinct impressionistic flavor because of the blurred harmony and the exotic violin line with the recurring augmented second E flat-Fl. Two con flicts of a minor second-D-E flat and F-F#-shown in circles, contribute to blur the D domi nant chord implied in the excerpt. This chord resolves deceptively to E flat major in m. 23, launching the second theme (the key of the second theme is the typical III in a minor key sonata form). ~ -==== ====- V 3 tr~ ... ====- Example 2. Mov. L mm. 18-23 In contrast to the previous sections, the second theme (Ex. 3) starts with a limpid harmony free of unresolved dissonances. -

Neoclassicism 8 Copy

THREE NEOCLASSICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO: STRAVINSKY’S DUO CONCERTANTE, PROKOFIEV’S VIOLIN SONATA NO. 2 IN D MAJOR, AND POULENC’S VIOLIN SONATA OP. 119 by JONG AH MOON (Under the Direction of Levon Ambartsumian) ABSTRACT In the early part of the twentieth century, the Neoclassical style was a strong influence on violin works by composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Francis Poulenc, and Sergei Prokofiev. Through a recording project and an accompanying document, I will introduce distinctive styles of Neoclassical violin music within three works: Stravinsky’s Duo concertante (1932), Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata No. 2 in D Major, Op. 94 bis (1943), and Poulenc’s Violin Sonata, Op. 119 (1942-1943). Through the performance and discussion, I explore ways to interpret these works in light of their Neoclassical elements. INDECX WORDS: Neoclassicism, Neoclassical violin music, Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Francis Poulenc, Duo concertante, Violin Sonata No. 2, Violin Sonata Op. 119. THREE NEOCLASSICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO: STRAVINSKY’S DUO CONCERTANTE, PROKOFIEV’S VIOLIN SONATA NO. 2 IN D MAJOR, AND POULENC’S VIOLIN SONATA OP. 119 by JONG AH MOON B. Mus., Ewha Womans University, South Korea, 2006 M.M., New England Conservatory, 2008 A Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2013 © 2013 Jong Ah Moon All Rights Reserved THREE NEOCLASSICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO: STRAVINSKY’S DUO CONCERTANTE, PROKOFIEV’S VIOLIN SONATA NO. 2 IN D MAJOR, AND POULENC’S VIOLIN SONATA OP. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 24 Online, Summer 2008

Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Volume 24 Summer 2008 Online Issue Contents Feature Articles p. 1 The Genesis of the Internationale-Viola-Forschungsgesellschaft and the Early American Viola Society: Factual and Anecdotal by Myron Rosenblum p. 8 Viola Power (1972) by Myron Rosenblum p. 10 The Pöllau Protocol (1965) by Franz Zeyringer and Dietrich Bauer p. 12 Reflections: Photos from the XXXVI International Viola Congress in Tempe, Arizona by Dwight Pounds p. 21 Book Review: Tom Heimberg’s Making a Musical Life by Dwight Pounds Departments p. 24 New Music Reviews: Michael Kimber by Kenneth Martinson The Genesis of the Internationale-Viola- Forschungsgesellschaft and the Early American Viola Society: Factual and Anecdotal By Myron Rosenblum of meeting Franz and his family. I was also invited to perform the Christoph Graupner It is hard to believe that we are at the 40th Concerto in D Major for Viola d’amore and Anniversary juncture of both the International Viola soli with strings with the local orchestra Viola Society and not long after, the American and with Franz as the violist. Franz showed me Viola Society, but here we are! For me, it his viola research and I was greatly impressed really began in college when I discovered the at his efforts to catalogue as much viola beauties and allure of the viola. I made the music—original and transcriptions—as he changeover from violin and had the good could locate or knew about. From my base in fortune to study with some viola luminaries: Vienna that year, I was able to go through the Lillian Fuchs, Walter Trampler, and William catalogues of both the Nationalbibliothek and Primrose. -

PINCHAS ZUKERMAN CELEBRATION Marking Pinchas Zukerman’S 70Th Birthday and the 25Th Anniversary of the Pinchas Zukerman Performance Program

PINCHAS ZUKERMAN CELEBRATION Marking Pinchas Zukerman’s 70th birthday and the 25th anniversary of the Pinchas Zukerman Performance Program WEDNESDAY, MARCH 20, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL WEDNESDAY, MARCH 20, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL PINCHAS ZUKERMAN CELEBRATION PROGRAM NICOLÒ PAGANINI Caprices for Solo Violin (1782–1840) No. 11 No. 24 Jesús Reina, violin HENRYK WIENIAWSKI Études-Caprices, Op. 18 (1835–1880) No. 2 in E-flat Major No. 4 in A Minor Bela Horvath, Asi Matathias, violin FELIX MENDELSSOHN Octet for Strings in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (1809–1847) Pinchas Zukerman, Asi Matathias, Bela Horvath, Anna Magrethe Nilsen, violin Jethro Marks, Cong Wu, viola Amanda Forsyth, David Geber, cello J. S. BACH Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor (1685–1750) Vivace Nathan Gendler, Pinchas Zukerman, violin Largo, ma non tanto SoHyun Ko, Pinchas Zukerman, violin Allegro Nathan Gendler, SoHyun Ko, violin ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 (1841–1904) No. 8 in G Minor (Furiant) Pinchas Zukerman, Conductor ABOUT THE PINCHAS ZUKERMAN PERFORMANCE PROGRAM Inaugurated in the fall of 1993, Manhattan School of Music’s Pinchas Zukerman Performance Program accepts a limited number of exceptionally gifted violinists and violists to study with internationally acclaimed musician Pinchas Zukerman. The class includes three to 10 young musicians, ranging from 15-year-old students to young career instrumentalists, as well as traditional-age conservatory students. Mr. Zukerman has adjusted his international performance schedule to permit him to work intensively with the students in a number of private lessons throughout the academic year. In addition, weekly lessons are given by Co-Director Patinka Kopec, who was selected by Mr. -

Thesis Title Page

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Music GERMAN AND FRENCH COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCES IN BÉLA BARTÓK’S ORCHESTRAL WORKS 1903-1924: CASE STUDIES IN A METHODOLOGY OF APPROPRIATION A Thesis in Musicology by Paul A. Sommerfeld © 2011 Paul A. Sommerfeld Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2011 The thesis of Paul A. Sommerfeld was reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles D. Youmans Associate Professor of Musicology Thesis Adviser Marica S. Tacconi Professor of Musicology Sue E. Haug Professor of Music Director, School of Music *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT Attending the Budapest premiere of Richard Strauss’s tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra in February 1902 profoundly influenced the subsequent trajectory of the young Béla Bartók’s musical endeavors. Afterward, the budding composer, who at the moment stood at a creative impasse, immersed himself in Strauss's orchestral works—Ein Heldenleben in particular—and thereafter resumed his compositional studies. In Strauss, Bartók discovered “the seeds of a new life,” a means with which he could create complex, serious music that he would unite with Hungarian characteristics—at least those elements that Europe as a whole associated with Hungarian identity at the time, meaning gypsy music and the verbunkos. Only with these “authentic” elements did Bartók believe he could craft a musical embodiment of the Hungarian ethos. Yet like many artists of the period, Bartók viewed Straussian modernism as a means to imbue his music with renewed vitality. Thus, he plunged into the tone poems of the world’s leading Teutonic composer. -

Takács Quartet 1928, in Brno by the Moravian String Quartet

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM NOTES Sunday, February 19, 2012, 3pm Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) primary beneficiary; Zdenka had to go to court Hertz Hall String Quartet No. 2, “Intimate Letters” to get that provision overturned.) The domestic tensions between the Janáčeks flared into a nasty Composed in 1928. Premiered on September 11, quarrel on New Years Day 1928, and Leoš deter- Takács Quartet 1928, in Brno by the Moravian String Quartet. mined to retreat to his cottage in his native vil- lage of Hukvaldy, but he was stuck in Brno for a Edward Dusinberre first violin In the summer of 1917, when he was 63, Leoš week finishing the opera The House of the Dead. Károly Schranz second violin Janáček fell in love with Kamila Stösslová, the He visited Kamila for two days before arriving Geraldine Walther viola 25-year-old wife of a Jewish antiques dealer in Hukvaldy on January 10th, and saw her again from Písek. They first met in a town in central at the performance of Katya Kabanova in Prague András Fejér cello Moravia during World War I, but, as he lived in on the 21st. A week later, from Hukvaldy, he Brno with Zdenka, his wife of 37 years, and she wrote to Kamila that he was beginning “a musi- lived with her husband in Písek, they saw each cal confession,” a new string quartet that he pro- PROGRAM other only infrequently thereafter and remained posed titling “Love Letters,” and which would in touch mostly by letter. The true passion seems call for a viola d’amore—the “viol of love”— to have been entirely on his side (“It is fortu- rather than the usual viola.