Hurdling to Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

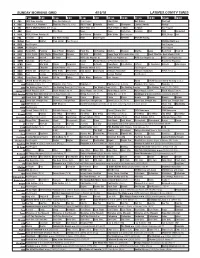

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

The Vulcan Historical Review Daniel Fowler, William Watt, Deborah Hayes, Rebecca Dobrinski, Kaye Cochran Nail, John Wiley, George O

Donna L. Cox, Colin J. Davis, David M. Brewer, Robert Maddox, Sameera Hasan, Jerry Snead, Stacy S. Simon, Eric Knudsen, Patricia A. Donna L. Cox, Colin J. Davis, David M. Brewer, Robert Maddox, Sameera Hasan, Jerry Snead, Stacy S. Simon, Eric Knudsen, Patricia A. Matthews, Scott M. Speagle, Will C. Holmes, J. D. Jackson, Aimee Armstrong Belden, Carol Balmer, Alan Dismukes, Jack E. Davis, Kenneth Matthews, Scott M. Speagle, Will C. Holmes, J. D. Jackson, Aimee Armstrong Belden, Carol Balmer, Alan Dismukes, Jack E. Davis, Ken- Homsley, Kurt E. Kinbacher, Jonathan L. Foster, Howard J. Fox III, Jeremy P. Soileau, Catherine L. Druhan, Andrew T. Baird, Averil Charles neth Homsley, Kurt E. Kinbacher, Jonathanth L. Foster, Howard J. Fox III, Jeremy P. Soileau, Catherine L. Druhan, Andrew T. Baird, Averil Ramsey, Mary B. Ashley, J. Kyle Irvin, Ellen M. Griffin, Tiffany Bence, Michelle L. Devins, Kelly Hamilton, Rhonda K. Mitchell, Roger K. Charles Ramsey, Mary B. Ashley,20 J. Kyle Irvin,ANNIVERSARY Ellen M. Griffin, Tiffany Bence, Michelle L.ISSUE Devins, Kelly Hamilton, Rhonda K. Mitchell, Steele, Lindsay Stainton-James, Sanford E. Jeames, Timothy L. Pennycuff, Donnelly F. Lancaster, Melinda Holm, Ron Bates, Jessica Lacher Roger K. Steele, Lindsay Stainton-James, Sanford E. Jeames, Timothy L. Pennycuff, Donnelly F. Lancaster, Melinda Holm, Ron Bates, Jes- Feldman, Horace Huntley, Cynthia A. Luckie, Elizabeth Wells, Becky Strickland, Wayne Coleman, Ashley C. Grantham, Allie A. Hanna, sica Lacher Feldman, Horace Huntley, Cynthia A. Luckie, Elizabeth Wells, Becky Strickland, Wayne Coleman, Ashley C. Grantham, Allie Robert W. Heinrich, Christopher M. Long, Jerry Tiarsmith, Jennifer Marie Wilson, Pamela E. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Document Number: 213270 Page 1 of 1 April 3, 2018 Re: AETN Networks

235 E 45th Street New York, NY 10017 April 3, 2018 Re: AETN Networks — Certification of Compliance with Children’s Television Act of 1990 and Closed-Captioning Programming Laws 1st Quarter — January 1, 2018 – March 31, 2018 To Whom It May Concern: This letter shall serve as certification under the Children’s Television Act of 1990 (the “Act”) that for the respective quarter ended March 31, 2018, A&E Television Networks, LLC (“AETN”) has been in compliance with the Act with respect to all of its networks (including in high definition). This letter shall also serve as certification that AETN has been in compliance with the closed-captioning requirements set forth in Section 79.1 of Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations, including Section 79.1(j)(2) with respect to its programming services for the quarter ended March 31, 2018. A&E Television Networks, LLC is dedicated to providing the best programming and customer service possible. I can be reached at (212) 210-9110 or via email: [email protected] with any questions or concerns. We thank you for your business and wish you continued success. Regards, Pamala Steward Director Distribution Operations cc: S. Plasse Document Number: 213270 Page 1 of 1 CHILDREN’S TELEVISION ACT COMPLIANCE In accordance with the Children’s Television Act of 1990, 47 U.S.C. § 503(b)(6)(B) and 47 C.F.R. §76.225 and 47 C.F.R. §76.1703 (the “Regulations”), CSTV Networks, Inc. d/b/a CBS Sports Network certifies that the CBS Sports Network programming service does not format or air any “children’s programming” -

Baker, Ragin Win At-Large Board Seats

2018 Gallery to MIDTERM open new ELECTION exhibit All results are unofficial Reception will pending certification. be on Thursday U.S. House of Representatives, SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 District 5 WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2018 $1.00 A2 Michael Chandler (Constitution) √ Ralph W. Norman (R) SUMTER SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF TRUSTEES RACE Archie Parnell (D) U.S. House of Representatives, District 6 √ James E. Clyburn (D) Alston, Ray, Gerhard R. Gressmann (R) Baker, Ragin Bryan Pugh (Green) State House of Representatives, McLeod get District 67 Brandon Humphries (Libertarian) √ Murrell Smith (R) win at-large area posts Sumter School Board, at large* (top 2 win seats) BY BRUCE MILLS, KAYLA ROBINS and DANNY KELLY Bonnie Disney [email protected] Bubba Rabon √ Frank Baker board seats Residents in Sumter School Board’s Dis- James Burton trict 1 knew they would have a new neigh- Jay Linginfelter Former school district superintendent to serve bor representing them on the Board of Lloyd Hunter Trustees after Tuesday’s election, and now √ Shawn Ragin BY BRUCE MILLS ter School Board’s at-large they know it will likely be Brian Alston. William Levan Byrd [email protected] board members moving forward. Alston is claiming victory in the four-can- Baker and Ragin were the top didate race for the seat that covers eight Sumter School Board, District 1* Former district Superinten- two vote-getters Tuesday in the precincts in the most northwestern portion Barbara Bowman dent Frank Baker and educator √ Brian L. Alston Shawn Ragin will likely be Sum- SEE AT LARGE, PAGE A6 SEE BOARD, PAGE A5 Caleb M. -

'Blue's Clues,' Introduce New Version of 'TMNT'

Nickelodeon to Reboot 'Blue's Clues,' Introduce New Version of 'TMNT' 03.07.2018 Nickelodeon opened the cable portion of this year's upfront presentations in New York City by touting more than 800 original hours of programming content, up 20 percent from last year. Nickelodeon Group President Cyma Zarghami also said the group's immediate focus is on the traditional linear programming landscape as well as new partnerships and technologies. The presentation to advertisers and the media community was held Tuesday night at the Palace Theater in Times Squares, the current home of SpongeBob SquarePants: The Musical. "We reinvent ourselves constantly and we do it for it for and with our audience front and center," said Zarghami. "In over four decades of doing just that, we have developed a unique brand position that resonates with passionate audiences. We have cultivated a safe high quality environment that families trust. And we have created an unmatched portfolio of original and enduring programming, great characters and great stories worth telling." "Our connection to you, our partners, is really just as vital," she added. "With great content and characters at the center, we can take, or follow, audiences anywhere and everywhere that they want to go: to TV, feature films, consumer products, musical festivals and live tours and into real world experiences or virtual ones." Mirroring the current primetime landscape, where the programming theme for next season is clearly all about revivals, Nickelodeon is no exception with upcoming new versions of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles - now called Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles - and Blue's Clues, with the search, at present, on finding a new host. -

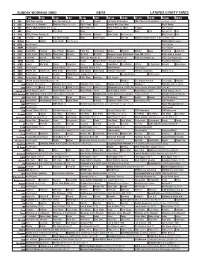

Sunday Morning Grid 4/15/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/15/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Short Films Bull Riding PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Naturally Health Champion Laureus Awards Hockey 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Rock-Park Vacation TBA NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program NASCAR NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Morning Glory ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Food 50 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Happy Yoga With Sarah Starr (TVG) Food: What the Heck Should I Eat? 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/8/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/8/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Sergio! Jim Nantz Remembers 2018 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Beverly Hills Dog Show World Recap 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program U.S. Na. Women’s Soccer Mexico at United States. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Stuart Little 2 ››› 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Retire Safe & Secure 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Mexico Primera Division Soccer (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Blooms for You Floral Boutique

Page 6 FREE YOUR COMMUNITY BANK Page 6 Page 7 Page 20 ndnd 424YearY2ear A WEEKLYTV MAGAZINE March 24 - March 30, 2018 Call 917-232-5501 www.TVTALKMAG.com 718 Broadway Blooms for You Bayonne, NJ Floral Boutique Refer a Friend to our Car Wash Club FULL SERVICE & Receive One Month of Car Wash Club FREE Only $8.00 (Offer valid for members of 6 months or more) DETAIL Regularly $11.96 SPECIALS Includes: Exterior Wash • Vacuum CAR WASH Inside Windows • Dust Dash Console • QUICK LUBE Offer Valid Tuesdays & Wednesdays Only Not to be combined with any other offer. • AUTO REPAIR With this coupon only. Expires 3/31/18 1505 Kennedy Blvd. (at City Line) Jersey City, NJ • Call 201-434-3355 Open 7 Days Mon.-Sat. 8 AM-6 PM • Sun. 8 AM-4 PM • All Major Credit Cards Accepted TV ‘The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling’ profiles a comic genius, warts ‘n’ all JEMMA PAWN CO. PIPELINE By George Dickie he evolved into a creative person who NJ’s Largest & Most Trusted By Jay Bobbin explored all of those issues in his work. Pawn Broker Q: What happened to the show “Madam It is said that the world’s greatest And so a lot of his work was about ego Fully Licensed & Insured Secretary”? I can’t seem to find it any- comedy often comes from a place of un- and people who have obstacles to con- INSTANT CASH more. — Brad Scheiner, via e-mail happiness — a place where Garry Shan- nection and obstacles to love. A: It’s still in CBS’ Sunday-night lineup, dling frequently took refuge. -

Outstanding Short Form Nonfiction Or Reality Series

2018 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Alex, Inc. Alone Together American Housewife Another Period Arrested Development Ash vs Evil Dead Atlanta Atypical Ballers Barry Baskets Better Things The Big Bang Theory black-ish Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Casual Champions Cobra Kai Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Curb Your Enthusiasm Dear White People Detectorists The Detour Dice Difficult People Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency Disjointed Divorce Easy The End Of The F***ing World Episodes Everything Sucks! Flaked Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty Ghosted GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie Great News grown-ish Happy! Haters Back Off! High Maintenance Hit The Road I'm Sorry Insecure Jane The Virgin Kevin Can Wait LA To Vegas Lady Dynamite The Last Man On Earth The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Living Biblically Loudermilk Love Man With A Plan Marlon The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel The Mick The Middle The Mindy Project Modern Family Mom Mozart In The Jungle New Girl No Activity Odd Mom Out On My Block One Day At A Time People Of Earth Playing House The Ranch Room 104 Roseanne Ryan Hansen Solves Crimes On Television Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Search Party Shameless She's Gotta Have It Silicon Valley SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superior Donuts Superstore Survivor's Remorse Sweetbitter Teachers This Close The Tick Transparent Tyler Perry's For Better Or Worse Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor Tyler Perry's The Paynes Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Vice Principals Vida Wet Hot American Summer: Ten Years Later White Famous Will & Grace Wrecked You Me Her You're The Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series Altered Carbon The Americans Animal Kingdom The Arrangement Arrow Being Mary Jane Berlin Station Billions Black Lightning The Blacklist Blindspot Blood Drive Blue Bloods The Bold Type Bosch The Brave Bull Chesapeake Shores The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Bayonne, NJ (Bet

SEE DAVE & SAVE! Jose Garza REALTOR®, ABR MARIO’S TRIANGLE TV Broker Associate FREE & APPLIANCE Authorized Sales & Service Page PIZZA Page 3 Page 9 17 Page 28 34th Anniversary JAN.1976 A WEEKLY MAGAZINE April 17-April 23, 2010 JAN. 2010 Tel. 201-437-5677 Visit Us On The Web at www.TVTALKMAG.com • Specialty Pies Thick or Thin • Calzones • Salads • Dinners • Hot Sandwiches Served On Our Own Homemade Brick Oven Bread “Taste The Difference” 53-55 Kennedy Blvd., Bayonne, NJ (bet. Gertrude & W. 3rd St.) Call 201-471-7351 For FREE Delivery Ad Pg. 20 Story Pg. 21 Silver Express Jewelry The Largest Selection of Sterling Silver Jewelry and Name Brand Watches In Town! Biggest Sale of the Year up to 80% off 602 Broadway (bet. 27th & 28th St. Next to PSE&G) Bayonne, N.J. Call (201) 339-0022 OPEN 7 DAYS & LATE NIGHTS DAYTIME 702 B’Way [USA] Law & Order: Criminal Intent (Mon) Law (cor. of 32nd St.) & Order: Special Victims Unit (Tue) JAG (Wed) Bayonne, N.J. [USA] Movie (Thu) “Desert Heat” [TNT] Supernatural Call 201-436-3440 CASHCASH FORFOR GOLD!GOLD! [TRAV] Caribbean Beach Resorts (Mon) Beach TRIANGLE TV Mon., Thurs. & Fri. 9-9 Goers Exposed (Tue) When Beaches Attack Tues. & Wed. 9-6; Sat. 9-5 RECORD HIGH PRICES (Wed) Secrets of Zion & Bryce (Thu) Top Ten Air Conditioners & Appliance r w e y Must Bring This Hawaiian Beach Resorts (Fri) PAID FOR YOUR GOLD! 11:02 [USA] Movie (Fri) “The Hard Corps” Coupon For An 11:25 [DISN] Tasty Time With ZeFronk (Tue, Thu) And Remember Dance-A-Lot-Robot (Wed, Fri) Pre-Season SEE DAVE YOU WILL BE AMAZED! Extra 10% More -

FREE Orsinicustomtees.Com Bayonneschooluniforms.Com

FREE Page 7 RESTAURANT Performance Page 13 Page 6 YOUR COMMUNITY BANK Page 8 ndnd 424YearY2ear A WEEKLYTV MAGAZINE May 5 - May 11, 2018 Call 917-232-5501 www.TVTALKMAG.com 5 West 8th St. Bayonne, NJ orsinicustomtees.com bayonneschooluniforms.com Refer a Friend to our Car Wash Club FULL SERVICE & Receive One Month of Car Wash Club FREE Only $8.00 (Offer valid for members of 6 months or more) DETAIL Regularly $11.96 SPECIALS Includes: Exterior Wash • Vacuum CAR WASH Inside Windows • Dust Dash Console • QUICK LUBE Offer Valid Tuesdays & Wednesdays Only Not to be combined with any other offer. • AUTO REPAIR With this coupon only. Expires 5/31/18 1505 Kennedy Blvd. (at City Line) Jersey City, NJ • Call 201-434-3355 Open 7 Days Mon.-Sat. 8 AM-6 PM • Sun. 8 AM-4 PM • All Major Credit Cards Accepted TV They may not be not ‘Dying’ Under New Management — but they’re not at all well PIPELINE By George Dickie big secret that sort of influences every- COMFORT RELAXATION By Jay Bobbin thing and really begins to be a major fac- Q: Now that Sandra Oh is on the series The first season of “I’m Dying Up tor in a lot of self-destructive behavior,” STATION “Killing Eve,” does that mean she’ll never Here” introduced viewers to a group of the actress explains. “You know, some return to “Grey’s Anatomy”? — Erin Scott, early ’70s Los Angeles comics with of it’s her fault, some of it isn’t but CHINESE MASSAGE & ACUPRESSURE via e-mail hopes of stardom and enough baggage there’s a lot of shame and self-loathing A: Regular readers of this column know to fill a fleet of 787s.