Number in Series 19; Year of Publication 1925

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dovestones Main Quarries

THE DOVESTONES QUARRIES O.S. ref. SE 022037 to 025040 By Chris Hardy (1987) Updated by Ian Carr (2012) Of it, one enthusiast has written: “It makes the Three Cliffs of Llanberis seem small beer”. Edward C. Pyatt: Where to Climb in the British Isles. (1960) SITUATION AND CHARACTER These huge man-made quarries dominate the eastern slopes rising above Dovestones Reservoir. The rock in all three is uniformly steep and The Main Quarry presents shattered walls and corners often more than 150 feet in height. This, and the steeply dropping hillside below the cliff, creates an atmosphere of unusual severity for gritstone. The Lower Left Quarry reaches a height of over 100 feet but is arranged in a rather more complex pattern of features, whereas the Lower Right Quarry is smaller, only 50 feet high, and possesses much less character (i.e. loose rock!) In The Main Quarry, the area of rock immediately right of White Slab has undergone radical change since the last guidebook (1976). It must be stressed: TREAT THIS SECTION WITH EXTREME CAUTION. Indeed, care should be exercised on all the seldom-frequented routes. Nevertheless, despite some loose and dirty holds, the rock is generally of good quality and despite the quarries’ poor reputation and unjustified lack of visitors, there are in fact many fine climbs that are well worth seeking out. Convenient belay stakes are in place above The Main Quarry and The Lower Right Quarry; small Cairns marks most of these. APPROACHES AND ACCESS From the car park below Dovestones Reservoir dam, walk along the road past the sailing clubhouse and yacht park until the bridge over Chew Brook is crossed. -

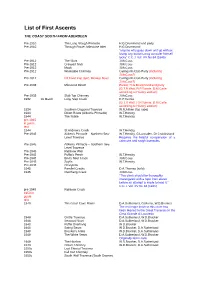

List of First Ascents

List of First Ascents THE COAST SOUTH FROM ABERDEEN Pre-1910 The Long Slough Pinnacle H.G.Drummond and party Pre-1910 Through Route, Milestone Inlet H.G.Drummond “anyone who goes down and up without losing any buttons may consider himself lucky” C.C.J. Vol. XV No 84 (1945) Pre-1912 The Slant J.McCoss Pre-1912 Creased Slab J.McCoss Pre-1912 Mask J.McCoss Pre-1912 Waterpipe Chimney Cairngorm Club Party (including J.McCoss?) Pre-1912 left hand trap dyke, Blowup Nose Cairngorm Club Party (including J.McCoss?) Pre-1933 Milestone Direct Parker, H.G.Drummond and party (G.T.R Watt, R.P.Yunnie. D.M.Carle according to History section) Pre-1933 Slab Top Chimney J.McCoss 1932 19 March Long Step Crack R.P.Yunnie (G.T.R Watt, R.P.Yunnie. D.M.Carle according to History section) 1934 Southern Diagonal Traverse W.N.Aitken (top rope) 1944 Direct Route (Aitken's Pinnacle) W.T.Hendry 1944 The Sickle W.T.Hendry pre-1945 in guide text 1944 St Andrew's Crack W.T.Hendry Pre-1945 Aitken’s Pinnacle – Northern Sea- W.T.Hendry, G.Lumsden, Dr Cruickshank Level Traverse Requires the helpful co-operation of a calm sea and rough barnacles Pre-1945 Aitken’s Pinnacle – Southern Sea- Level Traverse Pre-1945 Rainbow Wall Pre-1945 Puffin's Perch W.T.Hendry Pre-1945 Bird’s Nest Crack J.McCoss Pre-1945 Scylla W.T.Hendry Pre-1945 Charybdis 1945 Parallel Cracks D.A.Thomas (solo) 1945 Overhang Crack J.McCoss “This climb should be thoroughly investigated with a rope from above before an attempt is made to lead it.” C.C.J. -

CRESCENDO, 1939-56 99 Those Which Exemplified a New Standard of Rock Technique, Like Allain and Leininger's North Face of the Petit Dru (1935)

CRESCENDO, 1 939-56 • CRESCENDO 1939-1956 BY A. K. RAWLINSON 1 • I N this latest epoch in the story of mountaineering two themes pre vail. First, after the interruption of the war, comes the surge of exploration and achievement in the remoter mountain regions of the world. A century after the Alpine Golden Age has followed the Himalayan Golden Age ; the highest mountains of all have been climbed, and also many of the lesser peaks as more and more parties visit this greatest of ranges. Similarly, in the Andes and other distant regions the list of first ascents has lengthened annually. The second theme is the ever-increasing popularisation of moun taineering. This has been the constant feature of mountaineering history over the last hundred years, and especially between the wars. But since I 94 5 it has developed to a new degree, and in many countries. It has produced not only increasing numbers of climbers, but a general rise in the standard of technical achievement. In mountaineering, familiarity breeds both ambition and competence. Let us first consider climbing in the European Alps between 1939 and 1956, then, more briefly, in the other main ranges of the world, and finally in the Himalayas. • II Standards of difficulty and climbing technology are not the most important elements in mountaineering. But because, more than other • elements, they change, they must engage the attention of the historian, especially in mountains like the Alps, where a long history of intensive climbing has so narrowed the field for new endeavour. In the Alps the nineteen-thirties saw a definite advance in rock-climbing technique. -

2010 Alpine Club Antarctic Expedition

EXPEDITION REPORT 2010 Alpine Club Antarctic Expedition nd nd November 22 – December 22 2010 Dave and Mike high on the north ridge of Mt Inverleith Photo: Phil Wickens Contents SUMMARY .....................................1 WEATHER & SEA ICE ................... 16 Summary Itinerary....................1 Sea ice .................................. 16 Mountains Climbed ..................1 Weather................................. 17 INTRODUCTION ..............................2 RETURN JOURNEY....................... 18 MEMBERS .....................................3 COMMUNICATIONS....................... 18 SAILING SOUTH..............................4 CLOTHING, EQUIPMENT AND FOOD 19 WIENCKE ISLAND ...........................5 Clothing and Equipment........ 19 Access & Travel.......................5 Food ...................................... 20 Jabet Peak...............................6 PLANNING AND PERMITS .............. 21 DELONCLE BAY / LEMAIRE CHANNEL7 FINANCE..................................... 21 Access, Travel and Camp Sites7 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................ 22 Mt Nygren ................................8 Books .................................... 22 Mt False Shackleton / Faraday 9 Expedition Reports................ 22 Mt Matin .................................10 Maps ..................................... 22 Mt Cloos.................................11 Nautical Charts...................... 22 THE SAIL TO PARADISE HARBOUR .12 PARADISE HARBOUR / ANDVORD BAY13 Access, Travel and Camp Sites13 Mt Banck................................14 -

No Mystery No Adventure

AAC Publications No Mystery No Adventure New Friends and New Routes in East Greenland “Libecki! I have never been so fucking scared in my life!” Ethan Pringle’s yell from 80 feet above startled me to attention. I’d been lost in the view of electric-blue icebergs floating in the sea a mile away. We were 1,500 feet up—not even halfway—on a sheer granite tower above a remote fjord on Greenland’s east coast. Around us, spear-tipped summits stabbed into thick, gray-pink clouds. We had already been moving 14 hours, and I’d begun to think this route might take longer than the 48 hours we’d planned for our nonstop push. Suffering seemed a sure thing. Ethan has just danced through a spectacular, pinky-sized 5.12 crack, making it look like 5.9. He yelled again: “…But I am having so much fun! I’ve never been so psyched!” At that moment, I knew we’d not only climb this tower, we also were going to have a great time doing it. Ethan and I had only met once before this team-of-strangers expedition. We had never shared a rope. At base camp were two other members of our team, Angie Payne and Keith Ladzinksi, who also were strangers to me. Coming here together was not our idea…. I first met Ethan Pringle, a leading U.S. sport climber and boulderer, at a marketing meeting in California at the headquarters of Mountain Hardwear, one of our mutual sponsors. We were there to discuss a project where climbers with diverse skills and strengths would join forces somewhere remote among steep rock peaks. -

Froggatt Edge - 1

FROGGATT EDGE - 1 FROGGATT EDGE Introduction Froggatt Edge was original found by Margot Harkness in 1990, a discovery that marked the * New Zealand’s Best Gear Shop start of the climbing migration away from Wharepapa South (Castle Rock). Luke Newnham , was the first to put up climbs at Froggatt and kicked things off with, Monsterpiece Theatre, * Cafe Accommodation Bete Noire & Sunstrike, not a bad start! * Instruction Gear Clinics Luke then introduced the climbing world to Froggatt during the area’s first ever bouldering * Workshops Guiding Service comp. Following this a small group of Auckland based climbers set about bolting and * Hire Gear (Ropes) Crag Information climbing this expanse of unclimbed rock and within a year there were 38 routes at the crag. When Pete Mannings “CNI Rock” was published in 1992 it included these 38 routes, it also * Run by Climbers for Climbers listed the new route potential at Froggatt as being only “modest”. With this most moved for more information visit www.rockclimb.co.nz . Email [email protected] onto develop some of the area’s other crag’s leaving Luke Newnham, Ton Snelder and Telephone / Fax (07) 872 2533 Dave Vass to put up some of the crag’s harder lines. Andrew Wilson and co then pitched 1424 Owairaka Valley Road in and added a long list of first ascents. In 1996 Andrew Wilson then published a guide for Froggatt which include about 70 routes. The crag was re-bolted in 1997-98, during this re Wharepapa South bolting a lot of the lines between routes were filled in and new areas like Slug Wall were RD 7 Te Awamutu New Zealand opened up. -

S7 British Bouldering Championships

PETERBOROUGH MOUNTAINEERING CLUB SUMMER 2001 Three amigos in Paradise S7 British Bouldering Competition: Easter in Fontainebleau: PCW Competition: 6 Men and a dog!! Plus lots more... CONTACT EDITORS POINTS LETTER President: Clive Osborne Telephone: 01733 560303 E-mail: Just when you thought you’d been wiped off [email protected] the mailing list...along come the all familiar Chairman: Paul Eveleigh and welcoming pages of Take In to comfort Telephone: 01487 822202 you with the memory that you did pay your E-mail: membership this year, and yes! you are still [email protected] part of that warm and friendly body of climb- Treasurer: Dave Peck ers, walkers and adventurers of the PMC!!! Telephone: 01733 770244 E-mail: [email protected] We know you’ve all waited a long time for General this, and on behalf of a number of people I’d Secretary: Richard Ford like to apologise for there being such a long Telephone: 01778 342113 break since the last Take In dropped through your door. However I’d like to think of this E-mail: [email protected] period as a bit of “Tantric Editing” when New Members nothing seems to have happened for a long Secretary: Kevin Trickey time.... but having hung in there, (hopefully) Telephone: 01733 361650 the rewards will be great. E-mail: [email protected] Although our usual activities in the English Events countryside have been more difficult to pur- Coordinator: Rob Pontefract sue for most of this year, you’ll see from the Telephone: 01780 764333 articles in this Edition that a little crisis like Mobile: 07711 090999 Foot & Mouth hasn’t stopped everyone! E-mail: [email protected] There is also some important news for every Martina Harrison Tel:01733 349446 member of the PMC to be aware of about the Newsletter future of the wall. -

After the Matterhorn, 1865-80

AFTER THE MATTERHORN, r865-80 39 AFTER THE MATTERHORN 1865-1880 BY H. E. -L. PORTER HE year I 86 5 was an eventful one. On the lighter si_de it witnessed the birth of 'Alice in \Vonderland ' and the discovery of the first complete skeleton of the Dodo, a bird which in the course of centuries had become almost as mythical as the Phoenix. It was also memorable for two major tragedies. In April the civilised world was shocked by the news of the assassination of President Lincoln. In July the death of three Englishmen and a French guide on the hitherto unclimbed Matterhorn created a sensation of almost comparable magnitude. Before that date, we are told, 1 Leslie Step hen was _one of the heroes of the new sport of the upper middle class in mid-Victorian England, the conquest of the Alps, when the exploits of great climbers were followed with almost the same avidity as those of cricketers in the succeeding generation. After the accident the Press was unanimous in condemning a sport which could lead to such a tragedy. ' Why,' thundered The 1Ymes, ' is the best blood of England to waste itself in scaling hitherto inaccessible peaks, in staining the eternal snow and reaching the unfathomable abyss never to return ? ' Punch went so far as to pour scorn on the Rev. J. M'Cormick, Chaplain at Zermatt, for suggesting an appeal for funds to build a chapel there to commem orate the victims. Queen Victoria made a sad little entry in her diary about it, but refrained on this occasion from expressing her disapproval of dangerous Alpine expeditions to her Prime Minister, as she did in I 882. -

1960, a Brilliant Decade of Himalayan Climbing Termin Ated As Willi Unsoeld Placed a Small Crucifix Upon the Ice Crystals Rim Ming the Corniced Summit of Masherbrum

the Mountaineer 1961 Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office in Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and December by THE MOUNTAINEERS, P. 0. Box 122, Seattle 11, Wash. Clubroom is at 523 Pike Street in Seattle. Subscription price is $3.00 per year. The Mountaineers THE PuRPOSE: to explore and study the mountains, forest and water courses of the Northwest; to gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; to preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise, the natural beauty of Northwest America; to make expeditions into these regions in fulfillment of the above purposes; to encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. OFFICERS ANDTRUSTEES E. Allen Robinson, President Ellen Brooker, Secretary Frank Fickeisen, Vice-President Morris Moen, Treasurer John M. Hansen A. 1. Crittenden John Klos Eugene R. Faure Gordon Logan Peggy Lawton Richard Merritt William Marzolf Nancy B. Miller Ira Spring John R. Hazle (Ex-Officio) Judy Hansen (Jr. Representative) Joseph Cockrell (Tacoma) Larry Sebring (Everett) OFFICERS ANDTRUSTEES: TACOMA BRANCH John Freeman, Chairman Mary Fries, Secretary Harry Connor, Vice Chairman Wilma Shannon, Treasurer James Henriot, Past Chairman Jack Gallagher, George Munday, Nels Bjarke, Edith Goodman OFFICERS: EVERETI BRANCH Jim Geniesse, Chairman Dorothy Philipp, Secretary Ralph Mackey, Treasurer COPYRIGHT 1961 BY THE MOUNTAINEERS EDITORIAL ST AFF Nancy Miller, Edicor, Marjorie Wilson, Winifred Coleman, Pauline Dyer, Ann Hughes. the Mountaineer 1961 Vol. 54, No. 4, March 1, 1961-0rganized 1906-Incorporated 1913 CONT ENTS The Ascent of Masherbrum, K-1, by Richard E. -

Jarvis Books

JARVIS BOOKS incorporating GASTON’S ALPINE BOOKS MOUNTAINEERING CATALOGUE No. 130 Mount Everest Cigarette Cards item 169 RARE secondhand & out of print MOUNTAINEERING BOOKS 2 JARVIS BOOKS www.mountainbooks.co.uk BOOKS SPECIALISTS IN MOUNTAINEERING BOOKS Telephone: 01248 716021 International telephone: (+44) 1248 716021 Email [email protected] Grant Jarvis BEDW ARIAN, GLYN GARTH, MENAI BRIDGE, ANGLESEY, LL59 5NP, UK Private premises Established 1979 All books are subject to availability. ORDERING either: Telephone 01248 716021 or (International (+44) 1248 716021) Probably the quickest way to secure or enquire about a book. If you wish to pay by Credit or Debit Card, please state card type and name on card; card number, expiry date, plus 3-digit security number. Email [email protected] Please state your choice of books and we will get back to you with what’s available and the total cost. On receipt of the total amount please pay using any of the methods below. Letter (sent to the above address). PAYMENT: Credit or Debit Card. Please telephone or post stating card type and name on card; card number, expiry date, plus 3-digit security number. PayPal. If you wish to pay by PayPal please contact us first by email for the total cost (including postage) of the order; we will then send you a PayPal invoice by email with a link for paying. Cheques or Postal Orders. Please make payable to Jarvis Books on receipt of invoice: established customers on receipt of invoice with books. Sorry we can only accept payment in Sterling. 3 POSTAGE IS EXTRA: UK Postage and packing. -

Mitgliederzeitschrift Der Sektion Uto Nr. 1/2020 Januar/Februar

Schweizer Alpen-Club SAC Club Alpin Suisse Club Alpino Svizzero Club Alpin Svizzer Mitgliederzeitschrift der Sektion Uto Nr. 1/2020 Januar/Februar UTO AKTUELL UTO AKTUELL UTO ENGLISH Bericht des Jahres- Die neuen TL*innen Ice Climbing in Italy festes 2019 stellen sich vor Seite 10 Seite 11 Seite 31 FÜR PULVERSCHNEE UND ERSTE LINIEN Bergabenteuer beginnen bei uns. Beratung durch begeisterte Bergsportler, faire Preise und erstklassiger Service für deine Ausrüstung. Wir leben Bergsport. Filiale Zürich Binzmühlestr. 80 8050 Zürich-Oerlikon 044 317 20 02 baechli-bergsport.ch INHALTSVERZEICHNIS EDITORIAL 4 UTO TERMINE 6 UTO AKTUELL 7 – Das Jahr 2019 auf der Medelserhütte – Saisonrückblick 7 – Inserat Redaktor*in DER UTO 8 – Danke Fredy! 9 – Jahresabschluss im Landhus 10 – Vorstellung der neuen Tourenleiter*innen 11 – Julia Wunschs Uto-Tourenfazit 15 UTO SEKTION 16 – Nachruf Werner Ege 16 – Inserat Präsidium der Sektion Uto (Nachfolge Ueli Hintermeister) 17 – Wanderwoche Pontresina vom 24.-31. August 18 – Inserat Newsletter-Redaktor*in 19 – Inserat Leiter*in Ressort Hütten (Nachfolge Norbert Thalmann) 20 – Erstes SAC Uto «Hike and Fly»-Weekend 21 – Zu Wander- und Swisstopo-Karten 22 – Was steckt in unseren Skis? 23 – Mikrofasern: Die Spreu vom Weizen trennen (Teil 1) 24 UTO MUTATIONEN 28 UTO TOURENTIPP – Rallye rund ums Wichelhorn UTO ENGLISH – Cogne – Icefall climbing in the Italian Alps 31 – Emelie Forsberg: A natural talent 35 – Passion – and a pinch of romance 37 – A Training Book for Mountain Runners, Ski Mountaineers & Skimo Racers 38 UTO SENIORINNEN UND SENIOREN 39 – «Risottoessen» 39 – Informationen, Termine und Veranstaltungen 41 UTO KULTUR 43 – Ausstellung im Alpinen Museum, Bern: Iran Winter 43 – Alpen-Blicke.ch von Hans Peter Jost 45 IMPRESSUM 46 3 EDITORIAL Liebe Clubkameradinnen Jahr für Jahr dafür, dass die Sektion Uto und -kameraden beachtenswerte Leistungen zugunsten ih- rer Mitglieder und zum Teil auch zugunsten Wie in den meisten Jahren bietet sich das einer breiteren Allgemeinheit erbringt. -

The Pioneers of the Alps

* UMASS/AMHERST * 1 312066 0344 2693 3 ':.;.'':'-"-.: ,:'.-'. : '. "".':. '. -'C- C. D. CUNNINGHAM TAIN ABNEY F.R.S. '~*~**r%**t« iDaDDDnanDDDDnDDDDaDDnDaDnnnDDnp , o* J?**.!., *«nst UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY DQ 824 C82 DDODDDDDODDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDQDDDD THE PIONEERS OF THE ALPS C. D. CUNNINGHAM Captain W. de W. ABNEY, C.B., R.E., F.R.S. SECOND EDITION B ST ON ESTES AND LAURIAT. 1SSS TREASURE ROiOM C7I + JOHNS nOL'SE, C To Sir FRANCIS OTTIWELL ADAMS, K.C.M.G., C.B. Her Britannic Majesty's Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Swiss Confederation, &c, &c, &c. Honorary Member of the Alpine Club THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/pioneersofalps1859cunn PREFACE Tn the pages now presented to the reader will be found a collection of sketches of the lives and of portraits of those who first conquered the great peaks, opened out the mountain highways, and who may fairly be said to have "made possible that sport which so many of us enjoy every year in the Alps —men who are, or have been in their day, undoubtedly great guides. The present is a singularly favourable time for forming such a collection, as in addition to the portraits of those guides who have perfected the Art of Climbing, and who are still among us, we are able to obtain the likenesses of many of those who took the largest share in the work of exploring the Alps after the commencement of systematic mountaineering. The first point on which a decision was required was as to the mountain centres to which the selection of guides should be limited.