Criminal Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sri Lanka Law Reports

DIGEST TO THE Sri Lanka Law Reports Containing cases and other matters decided by the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka 2007 VOLUME 1 Consulting Editors : HON S. N. SILVA, Chief Justice HON P. WIJERATNE, J. President. Court of Appeal (upto 27.02.2007) Editor-in-Chief : K. M. M. B. Kulatunga, PC Additional Editor-in-Chief : ROHAN SAHABANDU PUBLISHED BY THE MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Printed at M. D. Gunasena & Company Printers (Pvt) Ltd. Price: Rs. 50.00 JUDGES OF THE appellate COURTS 2007 SUPREME COURT HON. SARATH N. Silva, P.C. (CHIEF JUSTICE) HON. DR. SHIRANI A. BANDARANAYAKE, J. HON. J. A. N. DE Silva, J. HON. NIHAL JAYASINGHE, J. HON SHIRANEE TilakawaRDENA, J. HON N. E. DISSANAYAKE, J. HON A. R. N. FERNANDO, J. HON R. A. N. GAMINI AMARATUNGA, J. HON. SALEEM MARSOOF, J. HON. ANDREW M. Somawansa, J. HON. D. J. DE S. BalapaTABENDI, J. COURT OF APPEAL HON. P. WIJAYARATNE, J. (President Of Court of Appeal Retired on 27.02.2007) HON. K. SRipavan, J. (President Court of Appeal from 27.02.2007) HON. CHANDRA EKANAYAKE, J. HON S.I. IMAM, J. HON L. K. WIMALACHANDRA, J. HON. S. SRIKANDARAJA, J. HON. W. L. R. Silva, J. HON. SISIRA DE ABREW, J. HON. ERIC BASNAYAKE J. HON. ROHUNI PERERA J. HON SARATH DE ABREW J. HON. ANIL FOONARATNE, J. HON. A. W. A. SALAM, J. iii LIST OF CASES Abeyfunawrdena V. Sammon and Others ............................................... 276 Ananda V. Dissananyake ........................................................................ 391 Aravindakumar V. Alwis and Others ........................................................ 316 Arpico Finance Co. -

Establishing a Constitutional Court the Impediments Ahead

ESTABLISHING A CONSTITUTIONAL COURT THE IMPEDIMENTS AHEAD CPA Working Papers on Constitutional Reform No. 13, January 2017 Dr Nihal Jayawickrama Centre for Policy Alternatives | www.cpalanka.org CPA Working Papers on Constitutional Reform | No. 13, January 2017 About the Author: Nihal Jayawickrama is the Coordinator of the UN-sponsored Judicial Integrity Group that drafted the Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct and related documents. He practised law before serving briefly, at the age of 32, as Attorney General and then as Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Justice from 1970-77. He was Vice- Chairman of the Sri Lanka Delegation to the United Nations General Assembly, a member of the Judicial Service Advisory Board and the Council of Legal Education, and a Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. Moving into academic life, he was Associate Professor of Law at the University of Hong Kong (1984-1997), and the Ariel F. Sallows Professor of Human Rights at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada (1992- 1993). As Chairman of the Hong Kong Section of the International Commission of Jurists, he was one of the principal commentators on constitutional and human rights issues in the period leading to the transfer of sovereignty. Moving out of academic life, he was Executive Director of Transparency International, Berlin (1997-2000), and Chair of the Trustees of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, London (2004-2007). Since 2000, he has served on several UN expert groups, been a consultant on judicial reform and the implementation of UNCAC, and worked with governments and judiciaries in Asia and the Pacific, Africa, and Eastern and Central Europe. -

Decisions of the Supreme Court on Parliamentary Bills

DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2014 - 2015 VOLUME XII Published by the Parliament Secretariat, Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte November - 2016 PRINTED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, SRI LANKA. Price : Rs. 364.00 Postage : Rs. 90.00 DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA UNDER ARTICLES 120, 121 AND 122 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR THE YEARS 2014 AND 2015 i ii 2 - PL 10020 - 100 (2016/06) CONTENTS Title of the Bill Page No. 2014 Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses 03 2015 Appropriation (Amendment ) 13 National Authority on Tobacco and Alcohol (Amendment) 15 National Medicines Regulatory Authority 21 Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution 26 Penal Code (Amendment) 40 Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) 40 iii iv DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2014 (2) D I G E S T Subject Determination Page No. No. ASSISTANCE TO AND PROTECTION OF VICTIMS 01/2014 to 03 - 07 OF CRIME AND WITNESSES 06/2014 to provide for the setting out of rights and entitlements of victims of crime and witnesses and the protection and promotion of such rights and entitlements; to give effect to appropriate international norms, standards and best practices relating to the protection of victims of crime and witnesses; the establishment of the national authority for the protection of victims of crime and witnesses; constitution of a board of management; the victims of crime and witnesses assistance and protection division of the Sri Lanka Police Department; payment of compensation to victims of crime; establishment of the victims of crime and witnesses assistance and protection fund and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. -

In the Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an Application under and in terms of Articles 17 and 126 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. 1. Athula Chandraguptha Thenuwara, 60/3A, 9th Lane, EthulKotte. (Petitioner in SC Application 665/12 [FR]) S.C. APPLICATION No: 665/2012(FR) 2. Janaka Adikari Palugaswewa, Perimiyankulama, S.C. APPLICATION No: 666/2012(FR) Anuradhapaura. S.C. APPLICATION No: 667/2012(FR) (Petitioner in SC Application 666/12 [FR]) S.C. APPLICATION No: 672/2012(FR) 3. Mahinda Jayasinghe, 12/2, Weera Mawatha, Subhuthipura, Battaramulla. (Petitioner in SC Application 667/12 [FR]) 4. Wijedasa Rajapakshe, Presidents’ Counsel, The President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (1st Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) 5. Sanjaya Gamage, Attorney-at-Law The Secretary of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (2nd Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) 6. Rasika Dissanayake, Attorney-at-Law The Treasurer of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (3rd Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) 7. Charith Galhena, Attorney-at-Law Assistant-Secretary of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (4th Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) Petitioners Vs. 1 1. Chamal Rajapakse, Speaker of Parliament, Parliament of Sri Lanka, Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte. 2. Anura Priyadarshana Yapa, Eeriyagolla, Yakawita. 3. Nimal Siripala de Silva, No. 93/20, Elvitigala Mawatha, Colombo 08. 4. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, No. 123/1, Station Road, Gangodawila, Nugegoda. 5. Rajitha Senaratne, CD 85, Gregory’s Road, Colombo 07. 6. Wimal Weerawansa, No. -

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

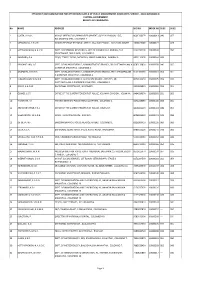

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

The Judiciary Under the 1978 Constitution

3 The Judiciary under the 1978 Constitution Nihal Jayawickrama The judiciary under the 1978 Constitution has to be assessed by reference to the constitutional framework within which it functioned, the period that preceded it, and the contemporary international standards. This chapter focuses on the superior courts of Sri Lanka; in particular, the Supreme Court. Judicial Independence At the core of the concept of judicial independence is the theory of the separation of powers: the judiciary, one of three basic and equal pillars in the modern democratic State, should function independently of the other two, the executive and the legislature. This is necessary because of the judiciary’s important role in relation to the other two branches. It ensures that the government and the administration are held to account for their actions. It ensures that laws are duly enacted by the legislature in conformity with the national constitution and, where appropriate, with regional and international treaties that form part of national law. To fulfil this role, and to ensure a completely free and unfettered exercise of its independent legal judgment, the judiciary must be free from inappropriate connections with, and influences by, the other two branches of government. Judicial independence thus serves as the guarantee of impartiality, and is a fundamental precondition for judicial integrity. It is, in essence, the right enjoyed by people when they invoke the jurisdiction of the courts seeking and expecting justice. It is a pre-requisite to the rule of law, and a fundamental guarantee of a fair trial. It is not a privilege accorded to the judiciary, or enjoyed by judges. -

Commission of Inquiry to Investigate the Involuntary Removal Or Disappearances of Persons in the Western, Southern and Sabaragamuwa Provinces As Well As Mr M.C.M

In exploring what constitutes a veritable minefield of contentious information in the current context in Sri Lanka, the author is indebted to Dr J. de Almeida Guneratne P.C., former Commissioner, 1994 Presidential Commission of Inquiry to Investigate the Involuntary Removal or Disappearances of Persons in the Western, Southern and Sabaragamuwa Provinces as well as Mr M.C.M. Iqbal, former Secretary to two Presidential Commissions of Inquiry into Involuntary Removal or Disappearances of Persons, with whom the perspectives of this research were shared. Research assistance was rendered by attorneys-at-law Prameetha Abeywickrema and Palitha de Silva, who also conducted interviews relevant to the analysis. Roger Normand, John Tyynela and Ian Seiderman of ICJ edited the report and provided invaluable substantive input and constant encouragement, which is deeply appreciated. 1 # & !& 0, ! &!&$!%% 07 1, $ + '$&+ %'$% 20 2, !!& '$+ 22 8060 #%##$#())*)$# 89 8070 '()%*!#$#())*)$#$6><7 8; 8080 $#%*!#$#())*)$#$6><= 8; 8090 ')(.)$*')$%%! 9; #" 0, $% & '$%)+% 41 1, "&+% 43 2, )!!& % 44 3, $!%'&! %& &!*'! ! & 46 9060 '"!)( := 9070 ##'$"#%( := 9080 (($ (( !!#($+!#( :> 90806 *"'%*'"( ;5 908070 "!""( ;6 908080 .!#)#( ;6 9090 ""#( ;6 90:0 '*(*+!( ;7 90;0 $!$ $(( ;8 90<0 #*#*,,( ;8 !'%%" ! $# 0, $!' 54 1, $-0883!%%! %! #'$+ 56 7060 #($#$""(($# ;< 7070 #&*'.#)$)) $# !3!"%1 '#$ #&*'.4 <6 7080 $ $!$""(($#$ #&*'. <8 7090 6>>61>8'(#)!$""(($#(36>>616>>84 <; 70:0 !)$#($#)6>>6'(#)!$""(($#( << 2, !%&-0883!%%! %! #'$+ &!%"$%""$ -

1 St Issue 2015 from the Editor Chief Justice of Sri Lanka

PRESIDENT st Mr.U.G.W.K.W. Jinadasa | District Judge - Kaduwela | [email protected] | 1 Issue - 2015 VICE PRESIDENT1 Mr.A.G.Aluthge | District Judge - Panadura | [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT2 Mr.P.P.R.E.H. Singappulige | Ad.District Judge - Colombo | [email protected] SECRETARY Mr.R.S.A.Dissanayake |District Judge - Puttalam | [email protected] ASSISTANT SECRETARY Mr.R.L.Godawela | Ad.District Judge - Panadura | [email protected] TREASURER 1 st Issue 2015 Mr.H.S.Ponnamperuma | Ad.District Judge - Kurunegala | [email protected] EDITOR Mr.J.A.Kahandagamage | District Judge - Horana | [email protected] ASSISTANT EDITOR Mr.D.M.A.Seneviratne | Ad.Magistrate - Nugegoda | [email protected] WEB MASTER Mr.N.D.B.Gunarathne | Magistrate - Kuliyapitiya | [email protected] COMMITTEE MEMBERS News Letter 01. Mr.T.D.Gunasekara D.J-.Kalutara 02. Mr.N.M.M.Abdulla Mag.-Batticaloa | [email protected] 03. Mr.H.S.Somaratne D.J.-Pugoda | hssomaratne @gmail.com 04. Mr.M.Ganesharajah D.J.-Mulativu | [email protected] 05. Mr.R.Weliwatta Mag.-Panadura | [email protected] 06. Mr.D.G.N.R.Premaratne Mag.Kurunegala | [email protected] 07. Mr.J.Trotsky Mag.-Bandarawela | trotskymarx1 @yahoo.com 08. Mr.K.A.T.K.jayatilake Mag.Gampaha | [email protected] 09. Mr.I.P.D.Liyanage D.J.-Hatton | [email protected] 10. Mr.R.A.D.U.N.Ranatunga D.J.Walasmulla | [email protected] 11. Mr.A.G.Alexrajah D.J.-Akkaraipattu | [email protected] 12. Mr.H.K.N.P.Alwis Mag.-Kegalle | [email protected] 13. -

Decisions of the Supreme Court on Parliamentary Bills (2016

DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2016 - 2017 VOLUME XIII Published by the Parliament Secretariat, Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte July - 2018 PRINTED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, SRI LANKA. Price : Rs. 430.00 Postage : Rs. 90.00 DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA UNDER ARTICLES 120 AND 121 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR THE YEARS 2016 AND 2017 i ii 2 - PL 10561 - 200 (2017/12) CONTENTS Title of the Bill Page No. 2016 Theravadi Bhikku Kathikawath (Registration) 07 Local Authorities Elections (Amendment) 16 Microfinance 20 Buddhist Temporalities (Amendment) 25 Budgetary Relief Allowance of Workers 31 National Minimum Wage of Workers 35 Right to Information 38 Homoeopathy 51 Fiscal Management (Responsibility) (Amendment) 53 Value Added Tax (Amendment) 57 Nation Building Tax (Amendment) 65 Engineering Council, Sri Lanka 69 Value Added Tax (Amendment) 76 2017 Foreign Exchange 88 Registration of Electors (Special Provisions) 97 Code of Criminal Procedure (Special Provisions) (Amendment) 103 Inland Revenue 105 Provincial Councils Elections (Amendment) 124 Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution 126 Provincial Councils Elections (Amendment) 138 iii DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2016 (2) D I G E S T Subject Determination Page No. No. Theravadi Bhikku Kathikawath 0 1 / 2 0 1 6 , 07 -15 (Registration) 02/2016 and 07/2016 to provide for the formulation and registration of Kathikawath in relation to Nikaya or Chapters of Theravadi Bhikkus in Sri Lanka; to provide for every Bhikku to act in compliance with the provisions of the Registered Kathikawath of the Nikaya or Chapter which relates to such Bhikku; to impose punishment on Bhikkus who act in violation of the provisions of any Registered Kathikawath, and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. -

Y%S ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;%Sl Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H

II fldgi — Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha w;s úfYI .eiÜ m;%h - 2011'03'15 1A PART II — GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA - 15.03.2011 Name of Notary Judicial Main Office Date of Language Division Appointment Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;%sl iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h w;s úfYI The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY wxl 1697$6 - 2011 ud¾;= 15 jeks w`.yrejdod - 2011'03'15 No. 1697/6 - TUESDAY, MARCH 15, 2011 (Published by Authority) PART II — LEGAL List of Notaries THE LIST OF NOTARIES IN SRI LANKA – 31st DECEMBER, 2010 Land Registry :Colombo Name of Notary Judicial Main Office Date of Language Division Appointment 1 Abdeen A. Colombo 282/23, Dam Street, Colombo 12 2 Abdeen M.N.N. Colombo Level 14, BOC Merchent Tower, 28, St Michael’s Rd, Colombo 3 3 Abdul Carder M.K. Colombo 4 Abdul Kalam M.M. Colombo 5 Abesekara O.U. Colombo 137, Polhena, Kelaniya 02.06.2008 Sinhala 6 Abeygunawardena S.D. Colombo 35D/4, Munamalgama, Waththala Rd, Polhena 7 Abeygunawardene W.D. Colombo CL/1/10,Gunasinghepura,Colombo 12 1950.04.22 Sinhala/English 8 Abeykoon A.M.C.W.P. Colombo 15,Salmal Uyana,Wanawasala,Kelaniya 2010.05.20 Sinhala 9 Abeykoon Y.T. Colombo BX5, Manning Town, Elvitigala Mw, Colombo 8 10 Abeynayaka E.H. Colombo 260/1,Kerawalapitiya Rd,Wattala 2010.07.23 English 11 Abeyrathne M.I. Colombo 12 Abeyrathne N. Colombo 251,Malabe Rd.,Thalangama 1982.03.16 Sinhala/English 13 Abeyrathne N. -

In the Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA A Bill titled - "An Act to provide for the vesting in the Government identified Underperforming Enterprises and Underutilized Assets" In the matter of an Application under Article 122(1) of the Constitution SC Special Determination No. 02/2011 AND NOW In the matter of an Application seeking the exercise of the inherent powers of the Supreme Court, to have the Special Determination made by a 3 Judge Bench on 24.10.2011 on the above titled Bill, under and in terms of Article 122, read with Article 123(3), of the Constitution, to be re-viewed and re-examined, as to whether the said Special Determination - has been made per-incuriam, without jurisdiction, ultra-vires the deeming provision in Article 123(3) of the Constitution, - was / is constitutionally ab-initio null and void and of no force and avail in law, and - has been made under circumstances of ‘perceived judicial bias and disqualification’ and if it be so, to declare the Special Determination of 24.10.2011 to be ab-initio a nullity Nihal Sri Ameresekere 167/4, Sri Vipulasena Mawatha Colombo 10. PETITIONER Vs. 1. Hon. Attorney General Attorneys General’s Department, Colombo 12. 2. Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, M.P. Speaker of Parliament of Sri Lanka Parliament of Sri Lanka Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte. RESPONDENTS TO: HER LADYSHIP THE CHIEF JUSTICE AND THEIR LORDSHIPS & LADYSHIPS THE OTHER HONOURABLE JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA On this 18th day of October 2012 The Petition of the Petitioner above-named, appearing in person, states as follows: 1. -

Attack on Air Force Camp: Seven Suspects Remanded DEATH Mr

2 Tuesday 26th September, 2006 Are you a lucky winner? DEVELOPMENT SUPIRI VASANA SATURDAY JAYODA VASANA SAMPATHA GOVI SETHA MAHAJANA SUWA SETHA Draw No: 274 Draw No: 07 FORTUNE SAMPATHA FORTUNE Draw No: 628 SAMPATHA Draw No: 816 Draw No.362 Draw No: 1747 Draw Date: Draw Date: Draw No.568 Draw Date: Date: Draw Date: 25-09-2006 14-09-2006 22 - 09 - 2006 24-09-2006 22-09-2006 Date: 23.09.2006 Date: 23-09-2006 Date: 25-09-2006 Winning Nos: Winning Nos: Super No:03 Bonus No. 19 Draw No. 1856 Symbol: Scorpio Winning Nos. Winnings Nos 29-50-52-54- 56 Winning Nos: 03 -18 - 27 - 28 Winning Nos : Winning Nos: Winning Nos. 23-25-30-33 S-06 - 13- 14- 54 Super No.02 6-6-0-0-2-3 34-36-46-58 C-07-31-39-69 R-33-11-11-77-66-99 Acid squirting teacher Killed: 580 journalists in remanded by Harischandra Gunaratna A school teacher charged with squirting acid on a woman colleague was yesterday remanded till September last 15 years worldwide 27 by Horana Magistrate. He was arrested on Friday by the Horana police on a complaint after the Five hundred and eighty journalists CPJ’s data show the vast majority of obtained, masterminds were brought to forces before being killed. attack at Royal College, Horana. The lost their lives doing their duty over the victims - 71 percent - are targeted for justice in just seven percent of cases. Iraq is the deadliest country for jour- victim of the attack, Swarna past 15 years, many on the orders of gov- murder in retaliation for their report- More than one in five victims covered nalists over the past 15 years, followed Suriyarachichi was attacked around ernment and military officials, a new ing.