Exploring Higher Order Risk Preferences of Drought Affected Farmers In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notification on CPC.Pdf

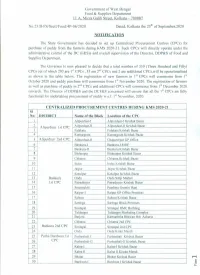

Government of West Bengal Food & Supplies Department 11 A, Mirza Galib Street, Kolkata - 700087 No.2318-FS/Sectt/Food/4P-06/2020 Dated, Kolkata the zs" of September,2020 NOTIFICATION The State Government has decided to set up Centralized Procurement Centres (CPCs) for purchase of paddy from the farmers during KMS 2020-21. Such CPCs will directly operate under the administrative control of the DC (F&S)s and overall supervision of the Director, DDP&S of Food and Supplies Department. The Governor is now pleased to decide that a total number of 350 (Three Hundred and Fifty) nd CPCs out of which 293 are 1st CPCs ,55 are 2 CPCs and 2 are additional CPCs,will be operationalised as shown in the table below. The registration of new farmers in 1st CPCs will commence from 1sI October 2020 and paddy purchase will commence from 1st November 2020. The registration of farmers nd as well as purchase of paddy in 2 CPCs and additional CPCs will commence from 1st December 2020 onwards. The Director of DDP&S and the DCF&S concerned will ensure that all the 1st CPCs are fully functional for undertaking procurement of paddy w.e.f. 1st November, 2020. CENTRALIZED PROCUREMENT CENTRES DURING KMS 2020-21 SI No: DISTRICT Name ofthe Block Location of the CPC f--- 1 Alipurduar-I Alipurduar-I Krishak Bazar 2 Alipurduar-II Alipurduar-II Krishak Bazar f--- Alipurduar 1st CPC - 3 Falakata Falakata Krishak Bazar 4 Kurnarzram Kumarzram Krishak Bazar 5 Alipurduar 2nd Cf'C Alipurduar-Il Chaporerpar GP Office - 6 Bankura-l Bankura-I RlDF f--- 7 Bankura-II Bankura Krishak Bazar I--- 8 Bishnupur Bishnupur Krishak Bazar I--- 9 Chhatna Chhatna Krishak Bazar 10 - Indus Indus Krishak Bazar ..». -

Human Resource Development of Birbhum District – a Critical Study

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 2, Ver. V (Feb. 2014), PP 62-67 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Human Resource Development of Birbhum District – A Critical Study 1Debasish Roy, 2Anushri Mondal M.Phil Scholar in Rabindra Bharati University, CSIR NET in Earth, Atmospheric, Ocean and Planetary Science. UGC NET in Geography, Rajiv Gandhi National Junior Research Fellow and Asst. Teacher Ahiran Hemangini Vidyayatan High school., M.A, NET Abstract: In this paper we discuss the human resource development of Birbhum District. The data have been collected from District Statistical Handbook, District census report of 2001 and District Human Development Report 2009.A large part of the Birbhum District is still backward with respect to human resource development. Aim of this paper is to study the cause of the backwardness of this district. “HRD is the process of determining the optimum methods of developing and improving the human resources of an organization and the systematic improvement of the performance of employees through training, education and development and leadership for the mutual attainment of organizational and personal goals” (Smith). HRD is an important topic of present time. It is considered by management professionals, as sub discipline of Human Resource Management( HRM), but many researchers have, broadened the scope and integrated the concept of HRD by looking it from socioeconomic angle and giving it other dimension such as physical, intellectual, psychological, social, political, moral and spiritual development. I. Introduction: Human Resource Development is the ultimate goal of National Development. HRD is the process of increasing the knowledge, the skills, and the capacities of all the people in a society. -

List of Gram Panchayat Under Social Sector Ii of Local Audit Department

LIST OF GRAM PANCHAYAT UNDER SOCIAL SECTOR II OF LOCAL AUDIT DEPARTMENT Last SL. Audit DISTRICT BLOCK GP NO ed up to 2015- 1 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I BANCHUKAMARI 16 2015- 2 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I CHAKOWAKHETI 16 2015- 3 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I MATHURA 16 2015- 4 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I PARORPAR 16 2015- 5 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I PATLAKHAWA 16 2015- 6 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I PURBA KANTHALBARI 16 2015- 7 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I SHALKUMAR-I 16 2015- 8 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I SHALKUMAR-II 16 2015- 9 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I TAPSIKHATA 16 2015- 10 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I VIVEKANDA-I 16 2015- 11 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I VIVEKANDA-II 16 2015- 12 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II BHATIBARI 16 2015- 13 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II CHAPORER PAR-I 16 2015- 14 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II CHAPORER PAR-II 16 2015- 15 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II KOHINOOR 16 2015- 16 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II MAHAKALGURI 16 2015- 17 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II MAJHERDABRI 16 2015- 18 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II PAROKATA 16 2015- 19 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II SHAMUKTALA 16 2015- 20 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II TATPARA-I 16 2015- 21 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II TATPARA-II 16 2015- 22 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II TURTURI 16 2015- 23 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DALGAON 16 2016- 24 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DEOGAON 18 2015- 25 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DHANIRAMPUR-I 16 2015- 26 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DHANIRAMPUR-II 16 2015- 27 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA FALAKATA-I 16 2015- 28 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA FALAKATA-II 16 2016- 29 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA GUABARNAGAR 18 2015- 30 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA JATESWAR-I 16 2015- 31 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA JATESWAR-II 16 2016- -

List of Common Service Centres in Birbhum, West Bengal Sl. No

List of Common Service Centres in Birbhum, West Bengal Sl. No. Entrepreneur's Name District Block Gram Panchyat Mobile No 1 Kartik Sadhu Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Bahiri-Panchshowa 9614924181 2 Nilanjan Acharya Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Bahiri-Panchshowa 7384260544 3 Sk Ajijul Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Bahiri-Panchshowa 8900568112 4 Debasree Mondal Masat Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Kankalitala 9002170027 5 Pintu Mondal Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Kankalitala 9832134124 6 Jhuma Das Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Kasba 8642818382 7 Koushik Dutta Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Kasba 9851970105 8 Soumya Sekher Ghosh Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Kasba 9800432525 9 Sujit Majumder Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Raipur-Supur 9126596149 10 Abhijit Karmakar Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Ruppur 9475407865 11 Rehena Begum Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Ruppur 9679799595 12 Debparna Roy Bhattacharya Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Sarpalehana-Albandha 7001311193 13 Proshenjit Das Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Sarpalehana-Albandha 8653677415 14 Asikar Rahaman Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Sattore 9734247244 15 Faijur Molla Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Sattore 8388870222 16 Debabrata Mondal Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Sian-Muluk 9434462676 17 Subir Kumar De Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Sian-Muluk 9563642924 18 Chowdhury Saddam Hossain Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Singhee 8392006494 19 Injamul Hoque Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Singhee 8900399093 20 Sanjib Das Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Singhee 8101742887 21 Saswati Ghosh Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Singhee 7550858645 22 Sekh Baul Birbhum Bolpur Sriniketan Singhee -

A Micro Level Analysis of Disparities in Health Care Infrastructure in Birbhum District, West Bengal, India

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 7, Issue 3 (Jan. - Feb. 2013), PP 25-31 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org A Micro Level Analysis of Disparities in Health Care Infrastructure in Birbhum District, West Bengal, India Sambit Sheet1 and Tutul Roy2 1 Assistant Teacher(Geography), B.M.S Public Institition, Burdwan, W.B.,India 2 Assistant Teacher(Geography),Usufabad Junior High School, Burdwan, W.B.,India Abstract: Regional disparities are caused by a number of factors that lead to misallocation, under utilization of resource, etc. Regional disparities lead to various economic, social and cultural problems. In micro-level study, regional disparity is a key factor for development. Especially, for health care infrastructures it becomes a key issue in that region. Health condition of any person shows its economic strength and working ability. It is the way of development.It is the primary need to human beings. In the present paper analyses has been made to study the imbalances in the level of development with spatial emphases on the regional dimension. To analyze the regional disparities of nineteen blocks of Birbhum district, eight variables have been selected.The Deprivation Index and Development Index of every blocks and every variables have done through calculation.In the analysis it has been observed that, the blocks of Sainthia, Bolpur-Santiniketan and Labpur are the more developed blocks in respect to health care infrastructure and the blocks of Nalhati-I, Suri-I, Mayureswar-I and II are the less developed blocks , which needs more planning to develop the health care infrastructure. -

West Bengal) Project Number: 37066 May 2008

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Initial Environmental Examination (West Bengal) Project Number: 37066 May 2008 India: Rural Roads Sector II Investment Program (Project 3) Prepared by [Author(s)] [Firm] [City, Country] Prepared by Ministry of Rural Development for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Prepared for [Executing Agency] [Implementing Agency] The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The summary initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. RURAL ROADS SECTOR II INVESTMENT PROGRAMME WEST BENGAL, INDIA (ADB LOAN NO. 2248-IND) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION REPORT BATCH II ROADS MAY 2008 TECHNICAL SUPPORT CONSULTANTS OPERATIONS RESEARCH GROUP PVT. LTD TABLE OF CONTENTS Section - 1 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1-1 GENERAL 1-1 1-2 PROJECT IDENTIFICATION AND LOCATION 1-1 1-3 RURAL ROAD CONSTRUCTION PROPOSALS 1-1 1.4 INITIAL ENVIRNMENTAL EXAMINATION 1-2 1-4.1 Corridor of Impact and Study Area 1-2 1-4.2 Field Visits 1-3 1-4.3 Secondary Data Collection 1-3 1-4.4 Primary Data Collection 1-3 1-5 Purpose of the Report 1-3 1-6 Acknowledgement 1-3 Section - 2 DESCRIPTION OF PROJECT 2-1 2.1 Type of project 2-1 2.2 Category of project 2-1 2.3 Need For Project 2-1 2.4 Location and Selection Criteria of Roads for IEE 2-1 2.5 Size or Magnitude -

District Birbhum Hydrogeological

87°15'0"E 87°30'0"E 87°45'0"E 88°0'0"E DISTRICT BIRBHUM 24°30'0"N HYDROGEOLOGICAL MAP 24°30'0"N Murarai-I Murarai-II ± Nalhati-I Nalhati-II i i Nad hman 24°15'0"N Bra 24°15'0"N Rampurhat-I Rampurhat-II d an kh ar Jh Mayureswar-I Mohammad Bazar 24°0'0"N 24°0'0"N Rajnagar Mayureswar-II M Murshidabad ayu raks hi N District adi Suri-I Sainthia Suri-II Labpur Khoyrasol Dubrajpur 23°45'0"N Legend 23°45'0"N Rock Type Alternating layers of sand,silt and clay Illambazar Bolpur Sriniketan Nanoor Hard clays impregnated with caliche nodules Laterite and lateritic soils Aj ay R iver Rajmahal trap-basalt Barddhaman District Sandstone and shale 23°30'0"N 23°30'0"N Black and grey shale with ironstone sandstone River 0 2.5 5 10 15 20 Pegmatite (unclassified) Kilometers Granite gneiss with enclaves of melamorphites District Boundary Quartzite Block Boundary Projection & Geodetic Reference System: GCS,WGS 1984 Symbol Rock Type Age Lithology Aquifer Description Hydrogeology Sand,silt and clay of flood plain, Multiple aquifer systems occur, Low to heavy-duty tubewells are Hard clays Jurassic to Late mature deltaic plain and in general, in the depth of feasible.The yield prospect is 23°15'0"N with caliche Holocene 23°15'0"N para-deltaic fan surface and 12-396m b.g.l. 7.2-250 cum/hr nodules, sand,silt, lateritic surface rajmahal trap basalt,laterite Ground water occurs,in the Dugwells and borewells or Shale,sand stone, Archaean to Soft to medium hard weathered residuum within dug-cum-borewells are feasible in silt stone, Triassic sedimentary rocks 6-12m b.g.l. -

Market Photos 1 - 3 BOLPUR MARKET

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL AGRICULTURAL MARKET DIRECTORY MARKET SURVEY REPORT YEAR : 2011-2012 DISTRICT : BIRBHUM THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING P-16, INDIA EXCHANGE PLACE EXTN. CIT BUILDING, 4 T H F L O O R KOLKATA-700073 THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING Government of West Bengal LIST OF MARKETS Birbhum District Sl. No. Name of Markets Block/Municipality Page No. 1 Bolpur Market Bolpur Municipality 1 2 Bahiri Hat Bolpur- Sriniketan 2 3 Debagram Hat - do - 3 4 Kopai Hat - do - 4 5 Sattore Hat - do - 5 6 Shriniketan Bazar - do - 6 7 Singhee Hat - do - 7 8 Batikar Hat Ilambazar 8 9 Ghurisha Hat - do - 9 10 Hansra Primary Hat - do - 10 11 Ilambazar Bazar - do - 11 12 Joydev Hat - do - 12 13 Kharui More Market - do - 13 14 Kurmitha Hat - do - 14 15 Mangaldihi Hat - do - 15 16 Sirsa Hat - do - 16 17 Sukh Bazar Hat ( Cattle ) - do - 17 18 Abadanga Hat Labhpur 18 19 Bipratikuri Hat - do - 19 20 Chowhatta Hat - do - 20 21 Dwarka Hat - do - 21 22 Hatia Hat - do - 22 23 Indus Hat - do - 23 24 Kurunnahar Hat - do - 24 25 Labhpur Hat - do - 25 26 Labulhata Hat - do - 26 27 Langanhata Hat - do - 27 28 Tarulia Hat - do - 28 29 Bangachatra Bazar Nanoor 29 30 Basapara Bazar - do - 30 31 Hate Serandi Hat - do - 31 32 Khujutipara Hat - do - 32 33 Kirnahar Hat - do - 33 34 Nanoor Bazar - do - 34 35 Natungram Hat - do - 35 36 Papuri Hat - do - 36 37 Bara Turigram Mayureswar- I 37 38 Dakshingram Hat - do - 38 39 Gadadharpur Bazar - do - 39 40 Kaleswar Mayureswar- I I 40 41 Kotasur Hat - do - 41 42 Mayureswar Hat - do - 42 43 Ramnagar Hat - do - 43 44 Satpalsa Hat - do - 44 45 Turigram Hat - do - 45 46 Beliapalsa Hat Murarai- I 46 47 Chatra Vegetable Hat - do - 47 48 Murarai Sabji Bazar - do - 48 49 Rajgram Gorur Hat - do - 49 50 Rajgram Hat Tala - do - 50 51 Ratanpur Hat - do - 51 52 Bipra Nandigram Hat Murarai- I I 52 53 Jajigram Hat - do - 53 54 Kushmore Hat - do - 54 55 Paikar Hat - do - 55 Sl. -

5. the State Govt. After Compilation of Skill Training Should Furnish the Block-Wise List of Name of Trainees and Their Address

No. 3/21(5)/2013-PP-I Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11th Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, C.G.O. Complex, Lodi Road, NewDelhi-110003, Dated: 20.11.2014 To The Pay & Accounts Officer, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Paryavaran Bhavan, New Delhi Subject: Grant in aid under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Multi sectoral Development Programme for Minority Concentration Blocks (MCBs) to Government of West Bengal for the year 2014- 15 for Birbhum District. Sir, I am directed to convey the sanction of the President for release of an amount of Rs.39, 37, 260 /- (Rupees Thirty Nine lakh Thirty Seven Thousand Two Hundred Sixty only) as 1 st instalment for the year 2014-15 to the Govt. of West Bengal for implementing Cybergram Initiative under "Multi Sectoral Development Programme for Minority Concentration Blocks in Birbhum district as per the details enclosed at Annexure I. The non-recurring grant may be released to the Govt. of West Bengal through CAS, Reserve Bank of India, Nagpur. 2. The expenditure is debitable to Demand No.68, Ministry of Minority Affairs Major Head- "3601" Grant-in-aid to State Governments, 02- Grants for State Plan Schemes (Sub Major Head), 378 -General- (Welfare of Schedule Casts/Schedule Tribes and Other Backward Classes and Minorities) -Other Grants (Minor Head), 01 - Multi sectoral Development Programme for minorities, 01.00.35 — Grant for creation of capital assets for the year 2014-15. 3. Since it is a fresh release for the plan of MsDP, no UC is pending. Utilization Certificate for this grant should be submitted by the grantee in the prescribed format within 12 months of the closure of financial year. -

Volunteer Name with Reg No State (District) (Block) Mobile No APSANA KHATUN (61467) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fanside

Volunteer Name with Reg No State (District) (Block) Mobile no APSANA KHATUN (61467) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fansidewa) 9547651060 RABINA KHAWAS (64657) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-I) 7586094862 NITSHEN TAMANG (64650) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Takda) 9564994554 ARBIND SUBBA (61475) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Takda) 7001894077 SANTOSH KUMAR PASWAN (61593) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Nakshalbari) 8917830020 SAMIRAN KHATUN (64837) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fansidewa) 7407206018 ANISHA THAKURI (64645) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 7679456517 BIKASH SINGHA (61913) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kharibari) 9064394568 PUSKAR TAMANG (64607) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 8436112429 ANIP RAI (61968) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 7047337757 SUDIBYA RAI (61976) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-II) 8944824498 DICHEN LAMA (64633) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-II) 9083860892 YOGESH N SARKI (62019) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kurseong) 7478305517 BIJAYA LAXMI SINGH (61586) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Matigara) 9932839481 SAGAR RAI (64619) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 7029143177 DEEPTI BISWAKARMA (61491) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 9734902283 ANMOL CHHETRI (61496) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kurseong) 9593951858 BIJAY CHANDRA SHARMA (61470) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-I) 9233666950 KHAGESH ROY (61579) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Nakshalbari) 8759721171 SANGAM SUBBA (61462) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Mirik) 8972908640 LIMESH TAMANG (64627) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 9679167713 ANUSHILA LAMA TAMANG (61452) WEST BENGAL -

District Sl No Name Post Present Place of Posting Birbhum 1 Dr

Present Place of District Sl No Name Post Posting Bharkata PHC under Birbhum 1 Dr. Paban Kr. Saha GDMO Md Bazar BPHC Birbhum 2 Dr. Anagh Banerjee GDMO Nalhati-I BPHC Jashpur PHC under Birbhum 3 Dr. Nimai Sadan Naskar GDMO Dubrajpur BPHC Birbhum 4 Dr. Bitti Sundar Mallik GDMO Sultanpur BPHC Kastogara PHC Birbhum 5 Dr. Usuf Ali GDMO under Chakmondala BPHC S.N.C.U Suri Sadar Birbhum 6 Dr. Priyabrata Chandra GDMO Hospital Barrah PHC, under Birbhum 7 Dr. Ashok Gupta GDMO Nakrakonda BPHC detailed at Bolpur Birbhum 8 Dr. Suman Chatterjee GDMO S.D.Hospital Birbhum 9 Dr. Himadri Kumar Laha GDMO Satpalsa BPHC Murarai-Rural- Birbhum 10 Dr. Asif Ahamed GDMO Hospital Birbhum 11 Dr. Debasis Sarkar GDMO Bolpur SDH Rampur PHC under Birbhum 12 Dr. Murari Mohan Mondal GDMO Md. Bazar BPHC Bhabanipur PHC Birbhum 13 Dr. Soumyo Sankar das GDMO under Rajnagar BPHC Sattor PHC under Birbhum 14 Dr. santosh kumar Roy GDMO Bolpur BPHC Ratma PHC under Birbhum 15 Dr. Arnab Kabiraj GDMO Mollarpur BPHC Birbhum 16 Dr. Siddhartha Biswas GDMO Paikar BPHC Kachujore PHC Birbhum 17 Dr. Mainak Ghosh GDMO under Barachaturi BPHC Birbhum 18 Dr. Bappaditya Halder GDMO Khoyrasole BPHC Rampurhat SD Birbhum 19 Dr. Kabita Barman GDMO Hospital Birbhum 20 Dr. Mohammad Aref Uz Zaman GDMO Paikar BPHC Panchowa PHC Birbhum 21 Dr. Goutam Basu GDMO under Bolpur BPHC Present Place of District Sl No Name Post Posting Sonarkundu PHC Birbhum 22 Dr. Trisanku Kumar Pal GDMO under Nalhati BPHC Birbhum 23 Dr. Subrata Kumar GDMO Rampurhat SDH Birbhum 24 Dr. -

Vol.1, No.2 2011 AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTIVITY ANALYSIS OF

Geo-Analyst ( ISSN 2249-2909), Vol.1, No.2 2011 AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTIVITY ANALYSIS OF BIRBHUM DISTRICT: A SPATIO-TEMPORAL CHANGE ASSESSMENT Sunil Saha* Abstract: This pape t ies to analy!e the spatio-te"po al #a iation o$ a% i&ultu al p o'u&ti#ity in (i )hu" 'ist i&t sin&e 2002- 0* to 200+-0,. The )lo&- .ise 'ispa ity in a% i&ultu al p o'u&ti#ity has )een &al&ulate' usin% Sin%h/s & op yield an' &on&ent ation in'i&es an-in% &oe$$i&ient. The e is % eat 'ispa ity in the a% i&ultu al p o'u&ti#ity at )lo&- le#el. The hi%hest le#el o$ a% i&ultu al p o'u&ti#ity has )een $oun' in Su i-II an' 0u a oi-I $o )oth yea an' lo.est p o'u&tivity has )een o)se #e' in 1a2na%a , 3hoy asole an' 4u) a2pu in )oth the yea s. The i""iti%a)le 'ispa ities o$ p o'u&ti#ity is )e&ause o$ hy' o-physi&al, e&ono"i& )a ie s, la&- o$ &ultu al "oti#ation an' la&- o$ p ope i"ple"entation o$ te&hnolo%i&al suppo ts. Keywords: Agricutural productivity, crop yield index, crop concentration index. Introd ct!on: A% i&ultu e has )een p a&tise' in In'ia sin&e ti"e i""e"o ial. At the p esent a%e in spite o$ te&hnolo%ical 'e#elop"ent an' e5pansion o$ se #i&e se&to "o e than 607 o$ total population in (i )hu" 4ist i&t is 'epen'ent on a% i&ultu e $o thei li#elihoo'.