OA Singh J Assessment of Nutritional.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Selected List

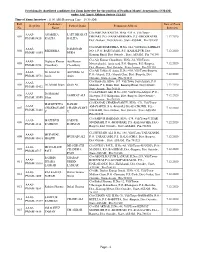

ROLL NO. NAME ADDRESS VENUE 14001 AARIFA BAGUM H.NO.-69, MAHARSHI DAYANAND WARD, RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY NEAR DR. C.S. BHARGAVA SAGAR, M.P., PIN- SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 470002 14002 A GYAN KR SINGH CHIMGAMATHAK PISHUM LEIRAK P-IMPHAL RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14003 A M ABDUJ JAMAN DOMPUR, KAMRUP. RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14004 A ROBINDRO SINGH NEOREMTHONG KHUPAM LEIKAI, P-LAMPHAL RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14005 A SAMARENDRA SINGH KHUMBONG BAZAR PO-LANGJING RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14006 A SOMENDRA SINGH TULIHAL AIRPORT MAYAI, P-TULIHAL RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14007 A SWAMI MEITEI CHIMGAMATHAK PISHUM LEIRAK P-IMPHAL RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14008 A. RABICHANDRA SINGH URIPAK POIAM LEIKAI PO-IMPHAL RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14009 A.Asangla c/o Temsu Directorate of geology & mining RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY Dmr SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14010 ABBASHISHA KHARMUJAI MAWLAI MAWDATBAKI (PATA) P-PHUDMAWRI, RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SHILLONG-8 SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14011 ABDUL BATEN CEO SECTION, 19 WING, AIR FORCE STATION, RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY BORJHAR, 781015, ASSAM. SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14012 ABDUL SAMAR SHAH HIYANG THANG P-WANGOI RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14013 ABDUR RAHMAN KEIKHU MANING LEIKAI RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14014 ABDUS SAHID GANDHIBASTI, SILPUKHURI, GHY. RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14015 Abel c/o Lotha baptist church Chumukidima RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14016 Abeni c/o Oreno Directorate of geology & mining RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY Dmr SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14017 ABHIJIT BARMAN THILOBASTI, THILO TE, CACHAR RAJDHAR BORAH HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, AZARA, GUWAHATI-17 14018 ABHIJIT BORAH C/O MR. -

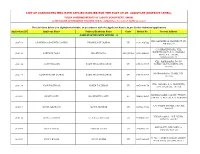

List of Candidates Called for Preliminary Examination for Direct Recruitment of Grade-Iii Officers in Assam Judicial Service

LIST OF CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION FOR DIRECT RECRUITMENT OF GRADE-III OFFICERS IN ASSAM JUDICIAL SERVICE. Sl No Name of the Category Roll No Present Address Candidate 1 2 3 4 5 1 A.M. MUKHTAR AHMED General 0001 C/O Imran Hussain (S.I. of Ploice), Convoy Road, Near Radio Station, P.O.- CHOUDHURY Boiragimath, Dist.- Dibrugarh, Pin-786003, Assam 2 AAM MOK KHENLOUNG ST 0002 Tipam Phakey Village, P.O.- Tipam(Joypur), Dist.- Dibrugarh(Assam), Pin- 786614 3 ABBAS ALI DEWAN General 0003 Vill: Dewrikuchi, P.O.:-Sonkuchi, P.S.& Dist.:- Barpeta, Assam, Pin-781314 4 ABDIDAR HUSSAIN OBC 0004 C/O Abdul Motin, Moirabari Sr. Madrassa, Vill, PO & PS-Moirabari, Dist-Morigaon SIDDIQUEE (Assam), Pin-782126 5 ABDUL ASAD REZAUL General 0005 C/O Pradip Sarkar, Debdaru Path, H/No.19, Dispur, Ghy-6. KARIM 6 ABDUL AZIM BARBHUIYA General 0006 Vill-Borbond Part-III, PO-Baliura, PS & Dist-Hailakandi (Assam) 7 ABDUL AZIZ General 0007 Vill. Piradhara Part - I, P.O. Piradhara, Dist. Bongaigaon, Assam, Pin - 783384. 8 ABDUL AZIZ General 0008 ISLAMPUR, RANGIA,WARD NO2, P.O.-RANGIA, DIST.- KAMRUP, PIN-781365 9 ABDUL BARIK General 0009 F. Ali Ahmed Nagar, Panjabari, Road, Sewali Path, Bye Lane - 5, House No.10, Guwahati - 781037. 10 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0010 Vill: Chamaria Pam, P.O. Mahtoli, P.S. Boko, Dist. Kamrup(R), Assam, Pin:-781136 11 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0011 Vill: Pub- Mahachara, P.O. & P.S. -Kachumara, Dist. Barpeta, Assam, Pin. 781127 12 ABDUL BATEN SK. General 0012 Vill-Char-Katdanga Pt-I, PO-Mohurirchar, PS-South Salmara, Dist-Dhubri (Assam) 13 ABDUL GAFFAR General 0013 C/O AKHTAR PARVEZ, ADVOCATE, HOUSE NO. -

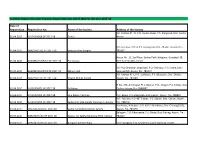

List of Eligible Candidate for the Viva-Voce of the Post of Peon Under the Establishment of District & Sessions Judge

List of eligible candidate for the Viva-Voce of the post of Peon under the establishment of District & Sessions Judge:::::Barpeta Sl No. & Name of the Candidate Father’s Name Address Educational Age Caste Roll No. Qualification 1 Sri Dhanjita Baishya Sri Pradip kr. Baishya Vill- Patbausi, P.O- Patbausi, Dist- Barpeta HSLC passed 24 years SC 2 Sri Luna Nath Sri Tapan Nath Vill- Jati Town P.O & Dist- Barpeta HSLC passed 19 years Gen 3 Rejaol Hussain Sikdar Lukman Hussain Vill & P.O- Bagodi, Dist- Barpeta (Assam) HSLC passed 23 years Gen 4 Sri Saurabh Jyoti Das Sri Jogen Das Vill & P.O- Duramari, Dist- Barpeta, Pin- HSLC passed 21 years OBC 781317 5 Gias Uddin Khosnabish Abdus Salam Khosnabish Vill- Gandhinagar (Metuakuchi), PO & Dist- IX passed 36 years Gen Barpeta 6 Sri Dipak Brahma Sri Ramesh Brahma Vill- Dhupaguri, PO- Simlaguri, Dist-Baksa HSLC passed 22 years ST Pin- 781313 7 Sri Manjit Bayan Lt. Kamala kanta Bayan Vill- Pathakhati, PO & Dist- Barpeta HSLC passed 32 years Gen 8 Sri Parameswar Kalita Jiten Kalita Vill & P.O- Gajia, Dist- Barpeta (Assam) IX passed 23 years Gen 781314 9 Fazila Begum Eakub Ali Vill- Kahibari, PO- Dhakua, Dist- Barpeta VIII passed 23 years Gen Pin- 781309 10 Sri Riniki Das Sri Rajani Das Vill- Patbausi, P.O- Patbausi, Dist- Barpeta X appeared 21 years Gen Pin- 781314 11 Nripen ch. Das Mahendra ch. Das Vill- Budarutup Ward No- 13 PO & Dist- IX passed 32 years Gen Barpeta 781301 12 Sri Karan Das Sri Karuna kanta Das Vill- Patbausi, P.O- Patbausi, Dist- Barpeta HSLC passed 18 years Gen Pin- 781314 13 Sri Ruma Mani Bhuyan Manmohan Bhuyan Vill- Metuakuchi PO- Santinagar, Barpeta HSLC passed 27 years Gen 781314 14 Sri Kamal Krishna Talukdar Kaurab ch. -

Provisionally Shortlisted Candidates for Zoom Interview for The

Provisionally shortlisted candidates for Zoom Interview for the position of Pradhan Mantri Arogyamitra (PMAM) under Atal Amrit Abhiyan Society (AAAS) Time of Zoom Interview : 11:00 AM (Reporting Time - 10:30 AM) Roll Candidate's Date of Zoom Regd No Father's Name Permanent Address No. Name Interview C/o-JAMUNA KALITA, H.No.-235 A, Vill/Town- AAAS- ANAMIKA LATE BHARAT 001 DIHJARI, P.O.-NANKARBHAIRA, P.S.-GHOGRAPAR, 7.12.2020 PMAM-9420 KALITA KALITA Dist.-Nalbari, Dist Outside-, State-ASSAM, Pin-781369 C/o-DAMODAR DEKA, H.No.-244, Vill/Town-SARIKAT AAAS- DAMODAR 002 BIKI DEKA NO 1, P.O.-BARUAJANI, P.S.-KAMALPUR, Dist.- 7.12.2020 PMAM-11955 DEKA Kamrup Rural, Dist Outside-, State-ASSAM, Pin-781380 C/o-Ajit Kumar Choudhury, H.No.-34, Vill/Town- AAAS- Digbijoy Kumar Ajit Kumar 003 Metuwakuchi , jania road, P.O.-Barpeta, P.S.-Barpeta, 7.12.2020 PMAM-2198 Choudhury Choudhury Dist.-Barpeta, Dist Outside-, State-Assam, Pin-781301 C/o-Afil Uddin Al Amin, H.No.-405, Vill/Town-Barpeta, AAAS- Dr Ariful Al Afil Uddin Al 004 P.O.-Alopati, P.S.-Alopati Char, Dist.-Barpeta, Dist 7.12.2020 PMAM-10731 Amin Amin Outside-, State-Assam, Pin-781127 C/o-Shaib Ali, H.No.-187, Vill/Town-Saru Arikati, P.O.- AAAS- 005 Dr Jahidul Islam Shaib Ali Mahtoli, P.S.-Boko, Dist.-Kamrup Rural, Dist Outside-, 7.12.2020 PMAM-13432 State-Assam, Pin-781136 C/o-SAWKAT ALI, H.No.-280, Vill/Town-Aditpur, P.O.- AAAS- Dr Mohidul 006 SAWKAT ALI Showpur, P.S.-Kalgachia, Dist.-Barpeta, Dist Outside-, 7.12.2020 PMAM-10590 Islam State-Assam, Pin-781319 MADHURJYA KANAK C/o-KANAK CHAKRAVARTY, -

List of Candidates Who Have Applied Earlier for the Post of Jr. Assistant (District Level)

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE APPLIED EARLIER FOR THE POST OF JR. ASSISTANT (DISTRICT LEVEL), UNDER COMMISSIONERATE OF LABOUR DEPARTMENT, ASSAM, AS PER EARLIER ADVERTISEMENT PUBLISHED VIDE NO. JANASANYOG/ D/11915/17, DATED 20-12-2017 The List Given below is in Alphabetical Order, in accordance with the Applicant Name ( As per Earlier Submited Application) Application ID Applicant Name Fathers/Husbands Name Caste Mobile No. Present Address NAME STARTING WITH LETTER: - 'A' VILL DAKSHIN MOHANPUR PT VII, 200718 A B MEHBOOB AHMED LASKAR NIYAMUDDIN LASKAR UR 9101308522 PIN 788119 C/O BRAJEN BORA, VILL. KSHETRI GAON, P.O. CHAKALA 206441 AANUPAM BORA BRAJEN BORA OBC/MOBC 9401696850 GHAT, P.S. JAJORI, NAGAON782142 VILL- MAIRAMARA, PO+PS- 200136 AASIF HUSSAIN ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 HOWLY, DIST-BARPETA, PIN- 781316 MOIRAMARA PO-HOWLI, PIN- 200137 AASIF HUSSAIN LASKAR ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 781316 VILL.-NAPARA, P.O.-HORUPETA, 200138 ABAN TALUKDAR NAREN TALUKDAR UR 9859404178 DIST.-BARPETA, 781318 NARENGI ASEB COLONY, TYPE IV, 203003 ABANI DOLEY KASHINATH DOLEY SC 7664836895 QTR NO. 4, GHY-26, P.O. NARENGI C/O SALMA STORES, GAR ALI, 202015 ABDUL GHAFOOR ABDUL MANNAN UR 8876215529 JORHAT VILL&P.O.&P.S.:- NIZ-DHING, 206442 ABDUL HANNAN LT. ABDUL MOTALIB UR 9706865304 NAGAON-782123 MAYA PATH, BYE LANE 1A, 203004 ABDUL HAYEE FAKHAR UDDIN UR 7002903504 SIXMILE, GHY-22 H. NO. 4, PEER DARGAH, SHARIF, 203005 ABDUL KALAM ABDUL KARIM UR 9435460827 NEAR ASEB, ULUBARI, GHY 7 HATKHOLA BONGALI GAON, CHABUA TATA GATE, LITTLE AGEL 201309 ABDUL KHAN NUR HUSSAIN KHAN UR 9678879562 SCHOOL ROAD, CHABUA, DIST DIBRUGARH 786184 BIRUBARI SHANTI PATH, H NO. -

ASDM) Issues Target Allocation List (Annexure 8

GOVT OF ASSAM ASSAM SKILL DEVELOPMENT MISSION KATABARI, DPS ROAD, NH-37 GARCHUK :: GUWAHATI-781035 No. ASDM-741/2018/326 Dated. 23/09/2019 Notice Assam Skill Development Mission (ASDM) issues Target Allocation List (Annexure 8) to the empanelled partners/training centres/new training centres based on submission of request letter submitted by TP/TC and inspection carried out as per instructions from competent authority. The Target Allocation List (Annexure 8) uploaded on the ASDM website (www.asdm.assam.gov.in) for reference TP/TC Sd/- Mission Director Assam Skill Development Mission Target Allocation (September 2019) Annexure -8 File Residential Sl.No File Lead FileIndex Number District TP TC Address SSC JobRole qpref Allotment Supervisor (Y/N) PMB Skill Development Valeur Fabtex Pvt Training Centre, Soliha Nagar, 1 Anuja Gupta Moumita ASDM 1123/2019 Tinsukia IT-ITES DDEO SSC/Q2212 N 60 Ltd Opp Bihu Toli, Near ME School, Tinsukia -786125 Retail sales 2 Akkas Ali Dipankar ASDM-397/2018 Biswanath Gramin Golia Gaon, BN Ghat Road Retail RAS/Q0104 Y 30 associate Distribution 3 Akkas Ali Dipankar ASDM-397/2018 Biswanath Gramin Golia Gaon, BN Ghat Road Power PSS/Q0102 Y 30 Lineman Donbosco Socio Tourism & F&B service 4 Akkas Ali Chandrani ASDM-592/2018 Sonitpur Technical Dekargaon, Mission Chariali THC/Q0301 Y 30 Hospitality steward Institute Donbosco Socio Tourism & Housekeeping 5 Akkas Ali Chandrani ASDM-592/2018 Sonitpur Technical Dekargaon, Mission Chariali THC/Q0208 Y 30 Hospitality Executive Institute Shree Maruti Teliyagaon, Majorati, -

11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM Onward) BOARD 1(Office

ROLL NAME ADDRESS DATE VENUE C/O-HEMA PHUKON, MECHAGARH LAHON PS-1 ABANITA PHUKON GAON, P.O-JATAKIA, P.S-NAZIRA, DIST- 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri SIVASAGAR Onward) P. R. Gharphalia, ADC, Sivasagar) PS-2 ABDUL ARIF TAMULI C/O-LT ROSE ALI, JENGONIKOTIA, 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri WARD NO. 1, P.O/DIST-SIVASAGAR Onward) P. R. Gharphalia, ADC, Sivasagar) PS-3 ABDUL HANNAN C/O- LT. ABDUL MANNAN, JENGONIKETIA CHARIALI,M.I.BORA 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri ROAD Onward) P. R. Gharphalia, ADC, Sivasagar) C/O-MANIKJAN ALI,DHAIALI WARD NO PS-4 ABDUL HANNAN 2, P.O-SIVASAGAR 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri Onward) P. R. Gharphalia, ADC, Sivasagar) C/O-MD ABDUR HUSSAIN, PS-5 ABDUL HUSSAIN BOLIAGHAT,P.O-BOLIAGHAT 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri Onward) P. R. Gharphalia, ADC, Sivasagar) PS-6 ABDUL KALITA C/O RICH ALI,NO 1 CHOULKORA ,PO- 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri CHAULKORA,DIST -SIVASAGAR,785667 Onward) P. R. Gharphalia, ADC, Sivasagar) C/O-SYED ABDUL HUSSAIN, NAZIRA BORTAL, PS-7 ABDUL MAZID WARS NO 10, P.S-NAZIRA, DIST-SIVASAGAR 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri Onward) P. R. Gharphalia, ADC, Sivasagar) C/O- ABDUL MANAN, SAMAGURI, P.O- PS-8 ABDUL MOFIQUE SAMAGURI, PIN-785680 11-Feb-2014 (10:00 AM BOARD 1(Office Chamber of Sri Onward) P. -

Societies Registered Under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the Year 2017-18

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2017-18 Date of Registration Registration No. Name of the Society Address of the Society Vill.-Khelma Pt.-VI, P.O.-Gumra Bazar, P.S.-Katigorah, Dist.-Cachar, 01-04-2017 CA/243/N/08 OF 2017-18 Sewak Assam. Vill.-Santipur, P.O. & P.S.-Sapatgram, Dist.-Dhubri, Assam, Pin.- 01-04-2017 DBR/250/T/01 OF 2017-18 Santipur Yuva Sangha 783337. House No.-15, 2nd Floor, Sankar Path, Hatigaon, Guwahati-38, 01-04-2017 KAM(M)/263/P/01 OF 2017-18 Paricharjya Dist.-Kamrup (M), Assam. Vill.-Pub Dharapur Jangrabari, P.O.-Dharapur, P.S.-Azara, Dist.- 01-04-2017 KAM(M)/263/P/02 OF 2017-18 Milijuli Club Kamrup (M), Assam, Pin.-781017. Vill.-Udmari Pt.-I, P.O.-Lakhiganj, P.S.-Bilasipara, Dist.-Dhubri, 02-04-2017 DBR/250/T/37 OF 2017-18 Pragati Mohila Samity Assam, Pin.-783348. H.No.-173, Ambicapur Pt.-I, Baoljur, P.O.- Singari, P.S.-Silchar, Dist.- 03-04-2017 CA/243/N/01 OF 2017-18 Yaifaloop Cachar, Assam, Pin.-7888007. 03-04-2017 CA/243/N/02 OF 2017-18 jana Kalyan Parishad P.O.-Kalain, P.S.-Katigorah, Dist.-Cachar, Assam, Pin.-788815 Vill.- Fakirtila, P.O.-NIT Silchar, P.S.-Silchar, Dist.-Cachar, Assam, 03-04-2017 CA/243/N/03 OF 2017-18 Sarbajanin Shib Mandir Parichalana Samity Pin.-788010. Runikhata, Ashrabari, P.O. & P.S.-Runikhata, Dist.-Chirang (BTC), 03-04-2017 CRG/261/D/01 OF 2017-18 Sadou Ajit Bathou Mandir Samity Assam, Pin.-783375. -

Colleges/Institutes

1 DISTRICTWISE LIST OF AFFILIATED COLLEGES/INSTITUTES UNDER DIBRUGARH UNIVERSITY Districts under the jurisdiction of Dibrugarh University 1. Tinsukia 2. Dibrugarh 3. Sivasagar 4. Charaideo 5. Jorhat 6. Majuli 7. Golaghat 8. Lakhimpur 9. Dhemaji 1 2 TINSUKIA DISTRICT Sl. COLLEGE NAME & PHONE NUMBER & Year of STREAM STATUS No ADDRESS EMAIL Establishment 1 ACE College 0374-2337772 TDC in Permitted 2010 Tulshiram Road [email protected] Commerce Opp. Tarachand Jallan Road Tinsukia, Pin -786125 (Assam) 2 College of Teacher 0374-2120601 B.Ed. Temporary 1993 Education, Tinsukia [email protected] Affiliation Dohutia Chuk P.O. Tinsukia Dist. Tinsukia, Pin 786125 (Assam) 3 C. T. College 7002403970 B.A Permitted 2018 Kali Mandir Road [email protected] B.Com Chirwapatty m PGDCA P.O. Tinsukia Dist. Tinsukia, Pin 786125 (Assam) 4 Digboi College 03751-264416 (O) B.A., B.Sc., Permanent 1965 P.O. Digboi, Dist. 9954487650 B.Com., Affiliation Tinsukia www digboicollege.org PGDCA, Pin 786171 (Assam) [email protected] P.G in Physics 5 Digboi B.Ed College 03751-268764, 264891 B.Ed. Temporary 2005 Borbil No.1, 9435003513 Affiliation Dist. Tinsukia [email protected] Pin 786171 (Assam) 6 Digboi Mahila 03751-264446 (O) B.A. Permanent 1981 Mahavidyalaya 266094 Affiliation Muliabari , P.O. Digboi 9435031768 Dist. Tinsukia www.dmm.co.in Pin 786171(Assam) [email protected] 7 Doomdooma College 03759-240800 (O) B.A., Permanent 1967 P.O. Rupai Saiding, 242532 (O) B. Com., BSc. Affiliation Dist. Tinsukia, Pin 9435712437 786153 (Assam) [email protected]; prakashjborthakur@yahoo. co.in 8 G.S. Lohia Girls’ 0374-2337786(O) B.Com Temporary 1996 College [email protected] Affiliation P.O. -

The Assam Tribune

80 YEARS OF SERVICE TO THE NATION PUBLISHED SIMULTANEOUSLY FROM GUWAHATI & DIBRUGARH RN-1127/57 TECH/GH – 104/2015-2017, VOL. 80, NO. 319, GUWAHATI, SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 25, 2018, Pages 20 Price Rs. 6.00 N E W S CAPSULE Magnificent Mary India, China agree to resolve ULFA-I linkmen border issue early GUWAHATI, Nov 24: scripts history SPL CORRESPONDENT the fundamental interests of the guidance provided by guidance and support to their In the wake of spurt in both the countries. Prime Minister Narendra work provided by the lead- the activities of the NEW DELHI, Nov 24: The Special Representa- Modi and President Xi Jin- ers at the Wuhan Summit, ULFA(I) across the Matches Cuban legend Felix Savon’s record of State, 17 linkmen of the winning six World Boxing Championship titles The Special Representatives tives of India and China on ping at their informal sum- the Special Representatives banned outfit were of India and China today re- the Boundary Question – mit at Wuhan in April, an of- agreed that pending the final detained from different solved to intensify efforts to National Security Advisor ficial spokesman of Union resolution of the boundary locations of the city as a achieve a fair, reasonable and Ajit Doval and State Coun- Ministry of External Affairs question, it is important to preventive measure, mutually-acceptable solution cillor and Minister of Foreign told newsmen here today. maintain peace and tranquil- police said today. – Staff to the vexed boundary ques- Affairs of China Wang Yi – met The two Special Repre- lity in the border areas, and Reporter tion at an early date. -

Approved in 326 Th Meeting of Executive

OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR :: DIBRUGARH UNIVERSITY DIBRUGARH | ASSAM | INDIA Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) N O T I F I C A T I O N Pursuant to the approval of the Executive Council of Dibrugarh University, accorded in the 326th Meeting of the Council held on 10 June, 2015, the candidates listed below are declared to have qualified for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) of Dibrugarh University for their doctoral research. The degree will be conferred on the candidates at the next Convocation of the University. Name of the Sl. Candidate Department Subject Examiner No. with Address for correspondence School : Science and Engineering [Total : 18] Dr. (Mrs.) Indira Barua, U.G.C. Emeritus Fellow, Dept. of Anthropology, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh. Dr. (Mrs.) Deepanjana Dutta Das, Dept. of Anthropology, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh. Smt. Bijoylaxmi Bhuyan, "Profile of Involvement And Workload Prof. R.K. Bhadra, C/o. Dr. N. Ray, Anthropology 1 Assessment of Tribal Farm Women : A Dept. of Sociology, K.N. Path, Na-Ali, Study Among the Bodos of Lower Assam". Jorhat-785002, Assam. North Bengal University, Raja Rammohanpur, Darjeeling-734430, West Bengal. Prof. (Mrs.) Chitra Prakash, Dept. of Resource Management, Institute of Home Science and Higher Education for Women, Avinashilingam University, Coimbatore-641043. Dr. Utpal Bora, Dept. of Chemical Sciences, Tezpur University, Napaam, Tezpur-28. "Development of Novel Transition Metal Sri Ankur Gogoi, Prof. Dilip Kr. Kakati, Based Catalyst for Carbon-Carbon and Chemistry 2 Nirmali Gaon, Dept. of Chemistry, Carbon Heteroatom Bond Formation Dibrugarh-786003, Assam. -

Hsslc ( Science - General ) Sl Beneficiar School / Total Marks Bank Name Bank Account No

OIL MERIT SCHOLARSHIP,2017 - HSSLC ( SCIENCE - GENERAL ) SL BENEFICIAR SCHOOL / TOTAL MARKS BANK NAME BANK ACCOUNT NO. IFSC Y NAME COLLEGE BRANCH 1 MISS SALT BROOK C/O. JOGINDER PAL STATE BANK OF GABHARUPATH 35134701426 SBIN0008989 GURPREET ACADEMY, SINGH, PADUM NAGAR- INDIA AR, KC GOGOI KAUR DIBRUGARH 2 BYE LANE-1, PATH, P.O.DIBRUGARH 786001, DIBRUGARH 2 SHRI SALT BROOK C/O.DIBRUGARH, TILOKANANDA M- UNION BANK OF MILAN NAGAR, 608702010002101 UBIN0560871 ARINDOM ACADEMY, GOSWAMI, RUPNAGAR, INDIA DIBRUGARH GOSWAMI DIBRUGARH DUWARA CHUK, P.O.RAJABHETA 786004, DIBRUGARH, M- 3 SHRI AMAN SALT BROOK C/O.8474041166 DR. RUPJYOTI SYNDICATE ADITYA 73912210003721 SYNB0007391 DATTA ACADEMY, DATTA, MALAKUBASA BANK HOSPITAL DIBRUGARH PATH, 1NO. KACHARI BRANCH GAON, P.O. BALRAGIMATH 786003, DIBRUGARH,M- 9435033496 4 MISS SALT BROOK C/O. KEJRIWAL BANK OF DIBRUGARH 30410100004777 BARBODIBRUG SANCHITA ACADEMY, HARDWARE STORES, BARODA KEJRIWAL DIBRUGARH SANTIPARA, P.O. DIBRUGARH 786001, 5 MISS SALT BROOK C/O.DIBRUGARH, DORODI M-SAIKIA STATE BANK OF NAMRUP 20175853530 SBIN0000223 ANNWESHA ACADEMY, BORAH, BVFCL COLONY, INDIA BORAH DIBRUGARH NAMRUP, P.O. PARBATPUR 786623, DIST. DIBRUGARH, M- 9435332108 6 SHRI SALT BROOK C/O. ARUN KR. UBI BANK DOOM DOOMA 0015010510509 UTBI0000361 SAMIRAN ACADEMY, BORDOLOI, TAPUBAN, BORDOLOI DIBRUGARH P.O. RUPAI SIDING 786153, DIST. TINSUKIA, M-9435442621 7 SHRI BHABEN SALT BROOK C/O. DHARMENDRA STATE BANK OF DOOM DOOMA 35309860435 ??????? MORAN ACADEMY, MORAN, NO.4 KAKOJAN, INDIA DIBRUGARH P.O. DOOMDOOMA 786151, DIST. TINSUKIA, 8 SHRI ANSAAR SALT BROOK C/O.M-8761890015 JAWED AHMED BANK OF DIBRUGARH 30410100003130 BARBODIBRUG AHMED KHAN ACADEMY, KHAN, PANCHALI, P.O. BARODA DIBRUGARH DIBRUGARH 786001, DIBRUGARH, M- 9435455111 9 MISS SALT BROOK C/O.