The Formulation of the Apostles' Creed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Thoughts About God … to the Afterlife

From Thoughts About God … To The Afterlife (parts 3 & 4 … of 8) Development of Thought Do the three “Abrahamic” faiths understand … God … in exactly the same way? Do Jews … Christians … and Muslims … worship the same God? There is a distinct chronology to the development of thought in Judaism … Christianity … and Islam. •There are 1300+ years between the Sinai event and the emergence of Christianity. •There are ~600 years from the emergence of Christianity to the emergence of Islam. Issues: •Are our beliefs about the afterlife compatible with our understanding of God? •In Judaism … Christianity … Islam … developed beliefs established vastly different criteria for “eternal” reward or punishment. Can the God who “revealed” these criteria (in scripture) possibly be the “same God”? Thoughts about G-d Judaism God A God of Creation … A God of Nature … A God of the Mountain(s) … A God of War … Protector of Israel A Merciless God … with those who are not His people … Where … exactly … is “Ethical Monotheism” ?? A God of Personal Encounter Toward Monotheism • “Thus saith HaShem, the G-d of Israel: Your fathers dwelt of old time beyond the River, even Terah, the father of Abraham, and the father of Nahor; and they served other gods.” (Joshua 24:2) Abram’s family … of Ur of the Chaldeans … was polytheist. • “When Israel was a child, then I loved him, and out of Egypt I called My son. The more they called them, the more they went from them; they sacrificed unto the Baalim, and offered to graven images.” (Hosea 10:1-2) Even after the Sinai event … and the occupation of the land God promised … the people worshipped the gods of the Canaanites. -

AGC Articles of Faith and Doctrine

Associated Gospel Churches - Articles of Faith and Doctrine The Trinity of the Godhead Part 2 - Trinitarian Controversies November 27, 2005 The Trinity of the Godhead II. The Trinity of the Godhead We believe that the Godhead eternally exists in three persons, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit; and that these three are one God, having precisely the same nature, attributes and perfection, and are worthy of precisely the same homage, confidence and obedience. Genesis 1:26, 3:22, 11:6-8; John 1:1-4; Isaiah 63:8-10; Matthew 29:19-20; Acts 5:3-4; 2 Corinthians 13:14; Mark 12:29; Revelation 1:4-6; Hebrews 1:1-3 The Trinity of the Godhead Agree of disagree? 1. There is one God who manifests Himself in three forms (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) at different times. 2. There is one God who exists in three Persons (Father, Son, Holy Spirit). 3. There are three gods who together form one God. 4. The Son was created by the Father before the world began. 5. The Son and the Holy Spirit are of similar substance as the Father. 6. The Son and the Holy Spirit are of the same substance as the Father. 7. The Father is identical to the Son, who is identical to the Holy Spirit. 8. The Son is subordinate to the Father, and the Holy Spirit is subordinate to both the Father and the Son. The Trinity of the Godhead • 3 statements summarize Biblical teaching on the Trinity: 1. God is three persons “We believe that the Godhead eternally exists in three persons, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit” 2. -

Efm Vocabulary

EfM EDUCATION for MINISTRY ST. FRANCIS-IN-THE-VALLEY EPISCOPAL CHURCH VOCABULARY (Main sources: EFM Years 1-4; Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church; An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church; The American Heritage Dictionary) Aaronic blessing – “The Lord bless you and keep you . “ Abba – Aramaic for “Father”. A more intimate form of the word “Father”, used by Jesus in addressing God in the Lord’s Prayer. (27B) To call God Abba is the sign of trust and love, according to Paul. abbot – The superior of a monastery. accolade – The ceremonial bestowal of knighthood, made akin to a sacrament by the church in the 13th century. aeskesis –An Eastern training of the Christian spirit which creates the state of openness to God and which leaves a rapturous experience of God. aesthetic – ( As used by Kierkegaard in its root meaning) pertaining to feeling, responding to life on the immediate sensual level, seeing pleasure and avoiding pain. (aesthetics) – The study of beauty, ugliness, the sublime. affective domain – That part of the human being that pertains to affection or emotion. agape – The love of God or Christ; also, Christian love. aggiornamento – A term (in Italian meaning “renewal”) and closely associated with Pope John XXIII and Vatican II, it denotes a fresh presentation of the faith, together with a recognition of the wide natural rights of human being and support of freedom of worship and the welfare state. akedia – (Pronounced ah-kay-DEE-ah) Apathy, boredom, listlessness, the inability to train the soul because one no longer cares, usually called “accidie” (AX-i-dee) in English. -

God in Three Persons: the Trinity How Can God Be Three Persons, Yet One God?

Chapter 14: God in Three Persons: The Trinity How can God be three persons, yet one God? Explanation and Scriptural Basis (226) God eternally exists as three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and each person is fully God, and there is one God. A) The doctrine of the Trinity is progressively revealed in Scripture. (226-231) 1) Partial Revelation in the Old Testament a) Although the doctrine of the Trinity is not explicitly found in the OT, several passages suggest or even imply that God exists as more than one person. (Gen. 1:26, 3:22; Isa. 6:8; Ps. 45:6-7; Heb. 1:8; Ps. 110:1; Matt. 22:41-46; Isa. 63:10; Mal. 3:1-2; Hosea 1:7; Isa. 48:16; Prov. 8:22-31) 2) More Complete Revelation of the Trinity in the NT(Matt. 3:16-17; 28:19; 1 Cor. 12:4-6; 2 Cor. 13:14; Eph. 4:4-6; Jude 20-21) B) Three statements summarize the biblical teaching. (231-241) 1) God is three persons. a) The fact that God is three persons means that each person of the Trinity is distinct from the other two persons. (John 1:1-2, 17:24; 1 John 2:1; Heb. 7:25; John 14:26; Rom. 8:27; Matt. 28:19; John 16:7; 1 Cor. 12:4-6) i) The Holy Spirit is a distinct person not just the power of God. (Eph. 4:4-6; John 14:26, 15:26; Rom. 8:26-27; 1 Cor. 2:10; Acts 16:6-7; Acts 8:29; Eph. -

CHURCH HISTORY the Council of Nicea Early Church History, Part 13 by Dr

IIIM Magazine Online, Volume 1, Number 27, August 30 to September 5, 1999 CHURCH HISTORY The Council of Nicea Early Church History, part 13 by Dr. Jack L. Arnold I. INTRODUCTION A. As the church grew in numbers, the false church (heretics) grew numerically also. It became increasingly more difficult to control the general thinking of all Christians on the fundamentals of the Christian Faith. Thus, there was a need to gather the major leaders together to settle different theological and practical matters. These gatherings were called “councils.” B. The first major council was in the first century: the Jerusalem Council. There were four major councils in early Church history which are of great significance: (1) the Council of Nicea; (2) the Council of Constantinople; (3) the Council of Ephesus; and (4) the Council of Chalcedon. II. HERESIES OPPOSED TO THE TRINITY A. The great question which occupied the mind of the early church for three hundred years was the relationship of the Son to the Father. There were a great many professing Christians who were not Trinitarian. B. Monarchianism: Monarchianism was a heresy that attempted to maintain the unity of God (one God), for the Bible teaches that “the Lord our God is one God.” Monarchianism, however, failed to distinguish the Persons in the Godhead, and the deity of Christ became more like a power or influence. This heresy was opposed by Tertullian and Hippolytus in the west, and by Origen in the east. Tertullian was the first to assert clearly the tri-personality of God, and to maintain the substantial unity of the three Persons of the Godhead. -

201 CHURCH HISTORY for DUMMIES Class #16: Modalism We

CHURCH HISTORY for DUMMIES Class #16: Modalism We now enter the beginning of the 4th century. Things are pretty stable as far as the church is concerned. Martyrdom is almost a thing of the past. Christians do not experience persecution as much as they did earlier. The emperor, Constantine, is a self-proclaimed Christian. Whether he really was or not, who knows? But he at least was sympathetic to the Gospel and the church. So there’s no heat or pressure coming down upon the church from the government. Outside the church, things have cooled off. Martyrdom and persecution is now a thing of the past. But there is a problem within the church now. There are people who call themselves believers, they call themselves Christians, but they are confessing something different than what the church has proclaimed for the first 3 centuries. In the 4th century, the main issue facing the church is this: How are we to understand the relationship between the God the Father and His Son, Jesus? What is the relationship between the Father and the Son? Is the Son created by the Father? Is Jesus eternal or did He have a beginning point in time? Is the Son’s essence, His nature, the same essence and nature as the God the Father? So, during the 2-4th centuries Christianity was struggling to reconcile the idea of a single God, as stated in Deuteronomy 6:4- Deuteronomy 6:4 “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one. - with the ending of Matthew’s Gospel which says- Matthew 28:19 Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit… How is God one and yet we are called to baptize people in the name of the Father, Son, and Spirit? So, some Christians struggled to understand and reconcile these 2 verses. -

Heretical Views of the Doctrine of the Trinity Gregg R

Denials of Orthodoxy: Heretical Views of the Doctrine of the Trinity Gregg R. Allison s this issue of SBJT explores the doctrine without its challenges. The purpose of this article of the Trinity—that God eternally exists as is to identify, describe, and critique these denials A 9 three persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy of the orthodox view of the Trinity. Spirit, each of whom is fully God, yet there is only one God—it is good to remember that this ortho- MONARCHIANISM: DENYING THE dox position was hammered out DISTINCTIONS OF THE THREE Gregg R. Allison is Professor of amid challenges to a “Trinitarian PERSONS Christian Theology at The Southern consciousness” that arose in the The first significant challenge to the early Baptist Theological Seminary. early church. By this consciousness church’s Trinitarian consciousness was the view Dr. Allison served many years as a I mean a sense, grounded in the that later came to be called monarchianism, a posi- staff member of Campus Crusade, teaching of Scripture, that devel- tion that emphasized “the unity of God as the only where he worked in campus ministry oped in the church as it reflected on monarchia, or ruler of the universe.”10 This error and as a missionary to Italy and 1 11 Switzerland. He also serves as the nature of God; baptized new developed two forms. Dynamic monarchianism the Secretary of the Evangelical Christians;2 prayed;3 worshipped;4 was promoted by two men named Theodotus Theological Society and the book constructed its ecclesiology;5 and (Theodotus the Tanner, Theodotus the Money- review editor for theological, 12 historical, and philosophical studies as it developed its apologetics Changer) and Paul of Samosata of Antioch. -

East Africa Baptist School of Theology July 15, 2017 Jeff Straub, Ph.D. Introduction to the Topic

East Africa Baptist School of Theology July 15, 2017 Jeff Straub, Ph.D. Introduction to the Topic Deut 6:4 “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. And these words that I command you today shall be on your heart.” If God is One, how then can He also be three? July 2017 Seminar on the Trinity 2 The Trinity in Early Christianity July 2017 Seminar on the Trinity 3 The Early Church 100 - 400 a time of uncertainty No more Apostles No settled biblical text Biblical books Non-biblical books The presence of false doctrine during the Apostolic era The Judiaizers The Gnostics July 2017 Seminar on the Trinity 4 The Early Church Challenges to the early church What do you think of Christ? Is he truly God? Is he truly man? If God is one, how can Jesus be God? Is Jesus the Father? Are there three gods? Without a settled Bible, how can these answers be known? July 2017 Seminar on the Trinity 5 A Church Divided – Controversies and Schisms The Trinitarian Controversy – the relationship between persons in the Godhead The Christological Controversy – Who is Jesus? God? Man? What are our authoritative sources of information? July 2017 Seminar on the Trinity 6 A Church Divided – Controversies and Schisms The Trinitarian Controversy – the relationship between persons in the Godhead Adoptionism – Jesus became Christ at baptism (aka dynamic monarchianism) Modalism and Sabellianism – God reveals himself in three ways (also called Patripassianism) Arianism -

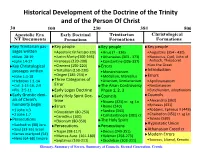

Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity

Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity and of the Person Of Christ 30 100 230 381 500 Apostolic Era Early Doctrinal Trinitarian Christological NT Documents Formations Formations Formations Key Trinitarian pas‐ Key people Key people Key people sages written •Apostolic fathers(60‐120) •Arius (? ‐ 336) •Augustine (354 ‐ 430) •Matt. 28:19 •Justin Martyr(100‐166) •Athanasius (303 ‐ 373) •Nestorius, Cyril, John of •John 14‐17 •Irenaeus (120‐200) •Constantine (306‐337) Antioch, Theodoret Key Christological •Clement (150‐220) Errors •Leo the Great passages written •Tertullian (150‐230) •Monarchianism Introduction •John 1:1‐18 •Origen (185‐254) e •Modalism, Marcellus Errors •Hebrews 1:1‐14 Three Categories of •Arianism, Semiarianism •Apollinarianism •Col. 1:15‐16, 2:9 Error The Arian Controversy •Nestorianism •Phi. 2:5‐11 Early Logos Doctrine Phase 1, 2, 3 •Eutichianism, adoptionism Early Gnostic deni‐ Early Holy Spirit Doc‐ Councils Councils als of Christ’s trine •Nicaea (325) cr. sg Ln •Alexandria (362) humanity begin •Ephesus (431) Errors •Rome (340) •Robbers, Ephesus II (449) •1 John 4:3 •Gnosticism (80‐250) •Sardica (343) •2 John 1:7 •Constantinople (381) cr. •Chalcedon (451) cr. sg Ln •Cerinthus (100) •Toledo (589) Persecutions •Ebionism (80‐350) The Holy Spirit Hypostatic Union •Sanhedrin (30) Jeru. Persecutions Persecutions •Saul (33‐35) Israel Athanasian Creed cr •Trajan (98‐117) •Decius (249‐251) •James martyred (54) •Marcus Aure. (161‐180) •Valerian (258‐273) Modern Errors •Nero (64‐68) Empire •Septimus (193‐211) •Diocletian (303‐311) •Socinus, Liberal, Kenotic Glossary, Summary of Errors, Summary of Councils, Eternal Generation, Creeds Historical Development Early Doctrinal Formations 100 - 230 A.D. -

1 Augustine and His Trinity: Modalistic Monarchianism and Tritheism

Augustine and His Trinity: Modalistic Monarchianism and Tritheism Unwittingly Embracing Two Contradictory Propositions Without Apology or Explanation by: Dan Mages Introducing the Indictment It is doubtful that Western Christian Trinitarian theology has been more influenced by anyone other than the greatest of the Latin Fathers. The one who became post apostolos ominium ecclesiarum magister, the leader of the church after all the apostles, Aurelius Augustinus, usually referred to simply as Augustine, bishop of Hippo1(354-430).2 Much of 21st century Western Christian trinitarian argumentation, analogies and ways of speaking about the trinity are typically unknowingly more or less a direct offspring of illustrations and discussions found in Augustine’s famous treaties on the subject, De Trinitas. It is my contention, that many of Augustine’s statements about the trinity in De Trinitas sadly vacillate between tritheism (belief in three Gods) and modalistic monarchianism (God the Father, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit are one person),3 leaving the reader with only a contradictory proposition. In order to hold two diametrically opposed propositions, that the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Sprit is God, and that there is only one God Augustine must defy logic, use incommunicable language, and distort Scripture. The Big Picture Augustine’s original contribution to trinitarian argumentation comes largely, but not exclusively from 15 books he composed over a span of 20 years (400-420) toward the end of his life, called De Trinitate.4 Before delving into some of the specific argumentation of his 1 Regius in Numidia in Roman North Africa 2 D.F. -

CHRISTIANITY Beginnings of Christianity • Jesus Born in Bethlehem and Raised in Nazareth

CHRISTIANITY Beginnings of Christianity • Jesus born in Bethlehem and raised in Nazareth • Quest for the historical Jesus • Synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke • Jesus complained about – Missed the meaning while obeying the letter of the Law – Concerned with cast outs of society – Religious hypocrisy • Differences in the message between Luke and Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount, second coming, communion, etc. Extent of Roman Empire at the time of Christ Christian Symbolism An interesting site for symbolism: http://home.att.net/~wegast/symbols/symbols.htm Constantine engaged Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge in Rome on October 28, 312 CE. In a dream, he saw a sign, “In hoc signes vinces.” Because of this single battle, the world changed. Paul’s Spin on Christianity • Paul moved Christianity from an Eastern to Western religion • Paul straddled split between Eastern and Western thought • Concern about universalizing the message and systematizing it • Had it not been for the Roman roads, Europe and therefore America wouldn’t be predominately Christian today • Constantine and Edict of Milan (313)—legalized Christianity • Later, it became the official religion of the Empire Language of Faith: a brief history of the fall of the Roman Empire-- • Diocletian divided the Empire into two administrative regions in 286: Western and Eastern Empire • Constantine moves capital to Byzantium and renames it Constantinople in 330 • Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire under the reign of Theodosius I in 380 • The ascendancy of Byzantium—started -

The Princeton Theological Review

THE PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL REVIEW. No. 4-0ctober, 1905. I. TERTULLIAN AND THE BEGINNINGS OF THE DOCTRINE OF THE TRINITY. FIRST ARTICLE. T is exceedingly impressive to see Christian Latin literature I Athena-like spring at once into being fully armed in the person of an eminently representative man, in whom seem summed up the promise and potency of all that it was yet to be. This is what occurred in Tertullian, whose advent and career provide a re markable illustration of the providential provision of the right man for the right place. Seldom has one been called to a great work who was better fitted for it by disposition and talents as well as by long and strenuous preparation. Ardent in temperament, en dowed with an intelligence as subtle and origina.l as it was aggres sive and audacious, he added to his natural gifts a profound erudi tion, which far from impeding only gave weight to the movements of his alert and robust mind. A jurist of note, he had joined to the study of law not only that of letters, but also that of medicine; born and brought up in the camp he had imbibed from infancy no little knowledge of the military art; and his insatiable curiosity had carried him into the depths of every form of learning accessible to his time and circurnstances, not even excepting the occult literature of the day. When he gave himself in his mature manhood to the service of Christianity, he brought in his hands all the spoils of an tique culture, smelted into a molten mass by an almost incredible passion.