Filling the Stands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

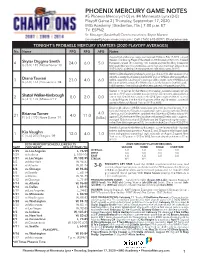

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) Vs

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) vs. #4 Minnesota Lynx (0-0) Playoff Game 2 | Thursday, September 17, 2020 IMG Academy | Bradenton, Fla. | 7:00 p.m. ET TV: ESPN2 Sr. Manager, Basketball Communications: Bryce Marsee [email protected] | Cell: (765) 618-0897 | @brycemarsee TONIGHT'S PROBABLE MERCURY STARTERS (2020 PLAYOFF AVERAGES) No. Name PPG RPG APG Notes Aquired by the Mercury in a sign-and-trade with Dallas on Feb. 12, 2020...named Western Conference Player of the Week on 9/8 for week of 8/31-9/6...finished 4 Skylar Diggins-Smith 24.0 6.0 5.0 the season ranked 7th in scoring, 10th in assists and tied for 4th in three-point G | 5-9 | 145 | Notre Dame '13 field goals (46)...scored a postseason career-high and team-high 24 points on 9/15 vs. WAS...picked up her first playoffs win over Washington on 9/15 WNBA's all-time leader in postseason scoring and ranks 3rd in all-time assists in the playoffs...6 assists shy of passing Sue Bird for 2nd on WNBA's all-time playoffs as- 3 Diana Taurasi 23.0 4.0 6.0 sists list...ranked 5th in the league in scoring and 8th in assists...led the WNBA in 3-pt G | 6-0 | 163 | Connecticut '04 field goals (61) this season, the 11th time she's led the league in 3-pt field goals... holds a perfect 7-0 record in single elimination games in the playoffs since 2016 Started in 10 games for the Mercury this season..scored a career-high 24 points on 9/11 against Seattle in a career-high 35 mimutes...also posted a 2 Shatori Walker-Kimbrough 8.0 2.0 0.0 career-high 5 steals this season in the 8/14 game against Atlanta...scored G | 6-1 | 170 | Missouri '19 in double figures 5 of the final 8 games of the regular season...scored 8 points in Mercury's Round 1 win on 9/15 vs. -

ATLANTA DREAM (1-0) at INDIANA FEVER (0-1) May 17, 2014 • 7 P.M

ATLANTA DREAM (1-0) at INDIANA FEVER (0-1) May 17, 2014 • 7 p.m. ET • TV: FOX Sports South Bankers Life Fieldhouse • Indianapolis, Ind. Regular Season Game 2 • Away Game 1 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 ..... NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 5 JASMINE THOMAS 9.0 3.0 2.0 Has never missed a game in her career May 16 ..... SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-9 • 145 • Duke (103 games played) May 17 ..... at Indiana (FSS) ..........................7 pm In last two years: Dream 16-8 when May 24 ..... at Chicago ....................................8 pm 5.0 4.0 1.0 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES she played; 2-9 in games she missed May 25 ..... INDIANA (SPSO) ......................6 pm 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 ..... SEATTLE (SPSO) ..................7:30 pm G 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 21.0 6.0 5.0 Scored go-ahead bucket with 42.9 June 1 ....... at Connecticut .............................3 pm seconds left Friday vs. San Antonio June 3 ....... LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ...........7 pm 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 ....... CHICAGO (SPSO) .....................7 pm F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 8.0 3.0 1.0 Missed all but six games during the June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) ...........7:30 pm 6-4 • 175 • Houton 2013 season June 15 .... at Washington .............................4 pm June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) .............12 pm C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 23.0 11.0 2.0 Extended her franchise record for June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) .............7:30 pm 6-5 • 190 • Brazil double-doubles to 59 Friday vs. -

Wnba Talent International Success

18 2015-16 NEBRASKA WOMEN'S BASKETBALL WNBA TALENT INTERNATIONAL SUCCESS Nebraska players have made an impact in recent years in the WNBA. In fact, over the last five years four Huskers have been chosen in the WNBA Draft, including No. 13 overall pick and first-team All-American Jordan Hooper (opposite page, top) in 2014. In 2010, first-team All-American Kelsey Griffin (top left) claimed the No. 3 overall pick in the WNBA Draft. In her first season with the Connecticut Sun, Griffin earned one of five spots on the 2010 WNBA All-Rookie Team. Griffin was No. 2 in rebounding among all rookies. Griffin completed her fifth WNBA season in 2014. Point guard Lindsey Moore (bottom left) became Nebraska's third WNBA first-round draft pick in history in 2013, going to the Minnesota Lynx with the No. 12 pick. Moore helped the Lynx win the WNBA title in her rookie season. Husker forward Cory Montgomery was a third-round WNBA pick of the New York Liberty in 2010. She continued her pro career in Europe and Australia. In 2008, Husker forward Danielle Page earned a WNBA spot as a free agent with the Connecticut Sun. Page spent the entire 2008 season with the Sun before spending her past seven seasons as one of the top players in Europe. In 2007, three-time first-team All-Big 12 guard Kiera Hardy was drafted in the third round by the Connecticut Sun. Hardy did not earn a final roster spot with the Sun, but spent two professional seasons overseas. -

Lynx Front Office Staff

SCHEDULE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2015 ROSTER PLAYERS ADMINISTRATION MEDIA 2014 SEASON 2014 PLAYOFFS HISTORY RECORDS PLAYOFFS PRESEASON OPPONENTS WNBA COMMUNITY AUGUSTUS BRUNSON CRUZ DANTAS GRAY JONES LISTON MOORE O’NEILL PETERS WHALEN WRIGHT ADDITIONAL RIGHTS THE COURTS AT MAYO CLINIC SQUARE The brand new training center has two basketball courts, with the Timberwolves and Lynx each having a primary court. It includes additional offices for coaches, scouts and staff, as well as expanded training and workout areas. The space is accessible to the community with the practice courts being available for youth basketball programs and games. - Approximately $20 million investment - Mortenson Construction is the Construction Manager - AECOM is the Architect/Engineering Firm - ICON Venue Group is the Owner’s Representative - 105,000 total square feet · 52,000 Timberwolves & Lynx Basketball Operations · 23,000 Timberwolves & Lynx Corporate Headquarters · 20,000 Mayo Clinic Space · 7,500 Mayo Clinic and Timberwolves & Lynx Shared Space · 2,000 Timberwolves & Lynx Retail Store - Two courts · Primary court for Timberwolves · Primary court for Lynx - Access to the Mayo Sports Medicine Clinic adjacent to the training center - Open for the 2014-2015 Season - Modern look and feel - More functional - Enhanced, enlarged workout area - Expanded, improved training area - Improved team classroom - Updated technology - Additional storage - Natural light - More transparent for the public - New Youth Basketball partnership opportunities - Creates hundreds of jobs · -

Bill Laimbeer Associate Head Coach

2017 NEW YORK LIBERTY MEDIA GUIDE CONTENTS Directory ......................................................................................................................2 2017 REGULAR SEASON SCHEDULE Front Office ..............................................................................................................3-6 Liberty Coaching Staff ............................................................................................7-14 MAY New York Liberty Roster .............................................................................................15 Saturday 13 SAN ANTONIO 3:00 PM Thursday 18 MINNESOTA (ESPN2) 7:00 PM Rebecca Allen ................................................................................................ 16-17 Tuesday 23 at Phoenix 10:00 PM Brittany Boyd ................................................................................................ 18-19 Friday 26 at Seattle 10:00 PM Cierra Burdick ......................................................................................................20 Tuesday 30 LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) 7:00 PM Tina Charles ................................................................................................... 21-24 JUNE Bria Hartley ................................................................................................... 25-26 Friday 2 DALLAS 7:30 PM Epiphanny Prince ........................................................................................... 27-29 Sunday 4 PHOENIX 3:00 PM Nayo Raincock-Ekunwe .......................................................................................30 -

2011 Atlanta Dream Roster

1 TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information WNBA Court Diagram …………………….103 Table of Contents . .2 MEDIA INFORMATION OPPONENTS 2010 Atlanta Dream Schedule . .3 Chicago Sky ……………………………..105 Quick Facts ……………… . ... 3 Connecticut Sun ………………………….105 General Media Information . …… 4 Indiana Fever …………………………….106 Los Angeles Sparks ……………………...106 DREAM FRONT OFFICE Minnesota Lynx ………………………….107 Office Directory …………………………….6 New York Liberty ………………………..107 Owner Bios ………………………………..7-8 Phoenix Mercury …………………………108 Front office Bios ………………………… 9-12 San Antonio Silver Stars …………………108 Seattle Storm ……………………………..109 MEET THE TEAM Tulsa Shock ………………………………110 Dream Roster & Pronunciations.……………14 Washington Mystics ……………………...110 Marynell Meadors ……………………….15-16 2010 Regular Season in Review …….111-116 Carol Ross …………………………………..17 Fred Williams ………………………………18 Sue Panek …………………………………..19 PHILIPS ARENA Kim Moseley ……………………………… 20 General Arena Information …………117-118 Seating and Ticket Information ………….119 Spotter‘s Chart ………………………………21 Dream Roster ………………………………..22 Alison Bales ………………………………23-24 Felicia Chester ……………………………….25 Iziane Castro Marques …………………..26-28 Erika De Souza ………………………….29-30 Lindsey Harding …………………………31-32 Sandora Irvin …………………………….33-34 Shalee Lehning ………………………….35-36 Sancho Lyttle ……………………………37-38 Angel McCoughtry ……………………...39-40 Shannon McCallum ………………………...41 Coco Miller ……………………………...42-44 Armintie Price …………………………..45-46 Brittainey Raven …………………………47-48 DREAM HISTORY Key Dates …………………………………50-51 All-Time Results ……………………………..52 Draft History ……………………………...53-54 All-Time Roster …………………………..55-57 All-Time Transactions ……………………57-59 2010 Season in Review …………………...60-61 2009 Season in Review …………..……….62-63 2008 Season in Review …………………...64-65 WNBA & QUICK FACTS WNBA Quick Facts ………………………67-73 WNBA Timeline …………………………73-87 2010 WNBA PR Contacts ……………….88-90 WNBA Award Winners ………………..91-101 2 SCHEDULE & QUICK FACTS 2011 Atlanta Dream Schedule ADDRESS: ATLANTA DREAM MAY 225 Peachtree Street NE 2011 PRESEASON Sun. -

ATLANTA DREAM (15-9) Vs. CONNECTICUT SUN (10-16) July 29, 2014 • 12:00 P.M

ATLANTA DREAM (15-9) vs. CONNECTICUT SUN (10-16) July 29, 2014 • 12:00 p.m. ET • TV: SPSO Philips Arena • Atlanta, Ga. Regular Season Game 25 • Home Game 14 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 ..... NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 5 JASMINE THOMAS 6.1 1.9 1.9 Has started every game but one this May 16 ..... SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-9 • 145 • Duke season May 17 ..... at Indiana (FSS) .......W, 90-88 (2OT) Averaging 16.4 points per game over May 24 ..... at Chicago (NBA TV) .......... L, 73-87 12.5 3.0 2.5 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES her last eight games May 25 ..... INDIANA (SPSO) ...... L, 77-82 (OT) 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 ..... SEATTLE (SPSO) ................W, 80-69 F 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 19.3 5.5 4.3 Leading the league in steals (2.43); June 1 ....... at Connecticut ....................... L, 76-85 would be second WNBA steals title June 3 ....... LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ....W, 93-85 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 ....... CHICAGO (SPSO) ..............W, 97-59 F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 12.8 9.0 2.5 Averaging 20.0 points per game in her June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) .........W, 85-82 6-4 • 175 • Houton last three games June 15 .... at Washington ......................W, 75-67 June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) ........W, 83-73 C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 13.8 9.3 1.3 Five straight games with single-digit June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) ...........W, 85-64 6-5 • 190 • Brazil points; had just one in first 19 games June 22 ... -

ATLANTA DREAM (9-4) at SAN ANTONIO STARS (7-7) June 26, 2014 • 8:00 P.M

ATLANTA DREAM (9-4) at SAN ANTONIO STARS (7-7) June 26, 2014 • 8:00 p.m. ET • TV: N/A AT&T Center • San Antonio, Texas Regular Season Game 14 • Away Game 6 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 ..... NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 5 JASMINE THOMAS 7.5 2.1 2.0 One of three players to start every May 16 ..... SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-9 • 145 • Duke game this season May 17 ..... at Indiana (FSS) .......W, 90-88 (2OT) Leads the league in 3-point field goal May 24 ..... at Chicago (NBA TV) .......... L, 73-87 10.5 2.9 1.8 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES pct. (.515) May 25 ..... INDIANA (SPSO) ...... L, 77-82 (OT) 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 ..... SEATTLE (SPSO) ................W, 80-69 G 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 20.3 5.4 4.3 45-of-48 (.938) from the free throw June 1 ....... at Connecticut ....................... L, 76-85 line in last nine games June 3 ....... LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ....W, 93-85 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 ....... CHICAGO (SPSO) ..............W, 97-59 F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 11.2 9.0 2.4 Six double-digit rebounding efforts June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) .........W, 85-82 6-4 • 175 • Houton this season June 15 .... at Washington ......................W, 75-67 June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) ........W, 83-73 C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 16.1 9.6 1.2 One of three players in WNBA top ten June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) ...........W, 85-64 6-5 • 190 • Brazil in points, rebounds and blocks June 22 ... -

WNBA EXPERIENCE Nebraska Players Have Made an Impact in Recent Years in the WNBA

24 | nebraska WOMEN'S basketball | 2011-12 WNBA EXPERIENCE Nebraska players have made an impact in recent years in the WNBA. In 2010, All-American Kelsey Griffin (top left) claimed the No. 3 overall pick in the WNBA Draft. In her first season with the Connecticut Sun, Griffin earned one of five spots on the 2010 WNBA All-Rookie Team. Griffin was No. 2 in rebounding among all rookies. Fellow Husker forward Cory Montgomery was also chosen in the third round of the 2010 WNBA Draft by the New York Liberty. She continued her professional career in Spain in 2010 and in Australia in 2011. In 2008, another Nebraska forward earned a WNBA spot, as Danielle Page (bottom right) claimed a spot with the Connecticut Sun as a free agent. Page spent the entire 2008 season with the Sun before heading overseas to continue her professional career. In 2007, three-time first-team All-Big 12 guard Kiera Hardy (bottom left) was drafted in the third round by the Connecticut Sun. Hardy did not earn a final roster spot with the Sun, but spent the 2007-08 season playing professionally in Iceland. She also played professionally in Europe in 2008-09, along with Page and former Husker Chelsea Aubry. Aubry has enjoyed success at the national level, helping the Canadian National Team to trips to the World Championships in 2006 and 2010. A team captain, Aubry has been a National Team member since 2005, and plays professionally in Australia. Anna DeForge (top right) enjoyed a long professional career after earning All-America honors at Nebraska in 1998. -

NEW YORK LIBERTY Liberty Statistics Presented By

NEW YORK LIBERTY Liberty statistics presented by MEDIA CONTACT: Vincent Novicki | [email protected] | (212) 465-5962 | @nyliberty | #ShowUp 2017 SCHEDULE/RESULTS WNBA PLAYOFFS 2ND ROUND: NEW YORK LIBERTY VS. WASHINGTON MYSTICS MAY NEW YORK LIBERTY (0-0) PRESEASON vs. Tuesday, May 2 vs. Los Angeles W, 81-65 1-0 WASHINGTON MYSTICS (1-0) (at Mohegan Sun Arena) Wednesday, May 3 vs. Chicago L, 75-86 1-1 Sunday, Sept. 10 • 5:00 PM (EST) (at Mohegan Sun Arena) New York, N.Y. (Madison Square Garden) Sunday, May 7 CONNECTICUT L, 57-79 1-2 TV: ESPN2 (at Columbia University) TALE OF THE TAPE (*Regular Season Stats) REGULAR SEASON PPG OPP. PPG FG% OPP FG% 3PT% OPP 3PT% FT% RPG APG SPG TO BLK Saturday, May 13 SAN ANTONIO W, 73-64 1-0 NEW YORK 79.7 76.6 .425 .408 .332 .333 .779 38.7 16.7 6.1 13.1 3.9 Thursday, May 18 MINNESOTA (ESPN 2) L, 71-90 1-1 Tuesday, May 23 at Phoenix W, 69-67 2-1 WASHINGTON 81.7 81.0 .416 .432 .317 .365 .843 36.3 16.4 6.3 12.1 4.6 Friday, May 26 at Seattle L, 81-87 2-2 Tuesday, May 30 LOS ANGELES (ESPN 2) L, 75-90 2-3 NEW YORK LIBERTY PROBABLE STARTERS JUNE Friday, June 2 DALLAS W, 93-89 3-3 NO. NAME POS. HT. PPG RPG APG MPG College Sunday, June 4 PHOENIX W, 88-72 4-3 1 Shavonte Zellous G 5-10 11.7 4.0 2.8 29.1 Pittsburgh Wednesday, June 7 ATLANTA W, 76-61 5-3 Averaging career highs in both rebounding and assists; ranks 3rd on the Liberty in scoring Sunday, June 11 SEATTLE W, 94-86 6-3 Wednesday, June 14 at Connecticut L, 76-96 6-4 7 Kia Vaughn C 6-4 5.8 4.9 0.7 19.6 Rutgers Friday, June 16 at Dallas W, 102-93 (OT) 7-4 -

ATLANTA DREAM (5-3) Vs. MINNESOTA LYNX (8-1) June 13, 2014 • 7:30 P.M

ATLANTA DREAM (5-3) vs. MINNESOTA LYNX (8-1) June 13, 2014 • 7:30 p.m. ET • TV: SPSO Philips Arena • Atlanta, Ga. Regular Season Game 9 • Home Game 6 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 ..... NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 5 JASMINE THOMAS 9.3 2.3 2.1 Has raised her scoring average every May 16 ..... SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-9 • 145 • Duke season May 17 ..... at Indiana (FSS) .......W, 90-88 (2OT) Leads the league in 3-point field goal May 24 ..... at Chicago (NBA TV) .......... L, 73-87 9.1 2.5 1.4 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES pct. (.625) May 25 ..... INDIANA (SPSO) ...... L, 77-82 (OT) 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 ..... SEATTLE (SPSO) ................W, 80-69 G 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 18.0 4.6 4.1 Fourth in the league in steals (2.6), June 1 ....... at Connecticut ....................... L, 76-85 sixth in scoring, tied for 11th in assists June 3 ....... LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ....W, 93-85 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 ....... CHICAGO (SPSO) ..............W, 97-59 F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 11.4 9.6 2.6 In last four games, averaging 14.0 June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) ...........7:30 pm 6-4 • 175 • Houton pts/10.3 reb/4.0 ast/2.5 stl June 15 .... at Washington .............................4 pm June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) .............12 pm C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 18.5 9.5 1.6 Earned first career Eastern Conference June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) .............7:30 pm 6-5 • 190 • Brazil Player of the Week award on June 9 June 22 ... -

2013 Chicago Sky Media Guide

CHICAGO SKY 2013 MEDIA GUIDE SKY TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 2012 REGULAR SEASON 2012 WNBA REVIEW Spotters Chart 3 REVIEW Regular Season 87 2013 Season Schedule 4 Regular Season Stats 43 Individual Leaders 88 Sky General Info/Training Facility 5 Season Notes 43 Team/Opponent Stats 89 Allstate Arena 6 2012 & 2013 Transactions 44 Team/Opponent Stats/Game 90 2013 Season Roster 7 Game by Game Results 45 Playoffs 91 In-Game Entertainment 8 Game by Game Stats 46 Sky in the Community 9 Individual & Team Highs 47 Sky Cares 10 Sky Individual Highs-Team Highs & Lows 48 WNBA Cares 11 Opponent Individual Highs- Team Highs & Lows 49 THE OPPONENTS Game Leaders 50 Atlanta 93-94 FRONT OFFICE Connecticut 95-96 Chicago Sky Directory 13 Indiana 97-98 Michael Alter 14 SKY HISTORY Los Angeles 99-100 Margaret Stender 15 Minnesota 101-102 52 Adam Fox 16 Franchise Firsts New York 103-104 53 Front Office 17 Draft History Phoenix 105-106 Honor Roll/All-Time Records 54 San Antonio 107-108 Leaders by Year 55-56 Seattle 109-110 All-Time Transactions 57-58 Tulsa 111-112 COACHES & TRAINERS 2011 Stats 59 Washington 113-114 2011 Game by Game Results 60 Pokey Chatman 19 2010 Stats 61 Wayne “Tree” Rollins 20 2010 Game by Game Results 62 Christie Sides 21 2009 Stats 63 MEDIA/WNBA Alan Vitelli 22 2009 Game by Game Results 64 Ann Crosby 22 INFORMATION 2008 Stats 65 Team Physicians 23 2008 Game by Game Results 66 Sky Broadcast Team 116 2007 Stats 67 Chicago Sky Media Outlets 117 2007 Game by Game Results 68 WNBA Directory/PR Contacts 118 2013 CHICAGO SKY TEAM 2006