Methods of Estrus Detection and Correlates of the Reproductive Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leopardus Tigrinus Is One of the Smallest Wild Cats in South America; and the Smallest Cat in Brazil (Oliveira-Santos Et Al

Mckenzie Brocker Conservation Biology David Stokes 20 February 2014 Leopardus Tigrinus Description: The Leopardus tigrinus is one of the smallest wild cats in South America; and the smallest cat in Brazil (Oliveira-Santos et al. 2012). L. tigrinus is roughly the size of a domestic house cat, with its weight ranging from 1.8-3.4 kg (Silva-Pereira 2010). The average body length is 710 millimeters and the cat’s tail is roughly one-third of its body length averaging 250 millimeters in length. Males tend to be slightly larger than the females (Gardner 1971). The species’ coat is of a yellowish-brown or ochre coloration patterned prominently with open rosettes (Trigo et al. 2013). Cases of melanism, or dark pigmentation, have been reported but are not as common (Oliveira-Santos et al 2012). These characteristics spots are what give the L. tigrinus its common names of little spotted cat, little tiger cat, tigrina, tigrillo, and oncilla. The names tigrillo, little tiger cat, and little spotted cat are sometimes used interchangeably with other small Neotropical cats species which can lead to confusion. The species is closely related to other feline species with overlapping habitat areas and similar colorations; namely, the ocelot, Leopardus pardalis, the margay, Leopardus weidii, Geoffroys cat, Leopardus geoffroyi, and the pampas cat, Leopardus colocolo (Trigo et al. 2013). Distribution: The L. tigrinus is reported to have a wide distribution from as far north as Costa Rica to as far south as Northern Argentina. However, its exact distribution is still under study, as there have been few reports of occurrences in Central America. -

Photographic Evidence of a Jaguar (Panthera Onca) Killing an Ocelot (Leopardus Pardalis)

Received: 12 May 2020 | Revised: 14 October 2020 | Accepted: 15 November 2020 DOI: 10.1111/btp.12916 NATURAL HISTORY FIELD NOTES When waterholes get busy, rare interactions thrive: Photographic evidence of a jaguar (Panthera onca) killing an ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) Lucy Perera-Romero1 | Rony Garcia-Anleu2 | Roan Balas McNab2 | Daniel H. Thornton1 1School of the Environment, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA Abstract 2Wildlife Conservation Society – During a camera trap survey conducted in Guatemala in the 2019 dry season, we doc- Guatemala Program, Petén, Guatemala umented a jaguar killing an ocelot at a waterhole with high mammal activity. During Correspondence severe droughts, the probability of aggressive interactions between carnivores might Lucy Perera-Romero, School of the Environment, Washington State increase when fixed, valuable resources such as water cannot be easily partitioned. University, Pullman, WA, 99163, USA. Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS activity overlap, activity patterns, carnivores, interspecific killing, drought, climate change, Funding information Maya forest, Guatemala Coypu Foundation; Rufford Foundation Associate Editor: Eleanor Slade Handling Editor: Kim McConkey 1 | INTRODUCTION and Johnson 2009). Interspecific killing has been documented in many different pairs of carnivores and is more likely when the larger Interference competition is an important process working to shape species is 2–5.4 times the mass of the victim species, or when the mammalian carnivore communities (Palomares and Caro 1999; larger species is a hypercarnivore (Donadio and Buskirk 2006; de Donadio and Buskirk 2006). Dominance in these interactions is Oliveria and Pereira 2014). Carnivores may reduce the likelihood often asymmetric based on body size (Palomares and Caro 1999; de of these types of encounters through the partitioning of habitat or Oliviera and Pereira 2014), and the threat of intraguild strife from temporal activity. -

Tick and Flea Infestation in a Captive Margay Leopardus Wiedii (Schinz, 1821) (Carnivora: Felidae: Felinae) in Peru

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 February 2014 | 6(2): 5501–5502 Note Tick and flea infestation in a captive Results: A male cub Margay was Margay Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821) presented for consultation in Lima, (Carnivora: Felidae: Felinae) in Peru Peru. Anamnesis revealed the Margay came from the region of ISSN Miryam Quevedo 1, Luis Gómez 2 & Jesús Lescano 3 Madre de Dios in Peru. Moreover, Online 0974–7907 Print 0974–7893 the Margay had been kept as 1,3 Laboratory of Animal Anatomy and Wildlife, School of Veterinary Medicine, a pet for about 15 days, during OPEN ACCESS San Marcos University, 2800 Circunvalación Avenue, Lima 41, Peru 2 Laboratory of Veterinary Preventive Medicine, School of Veterinary Medicine, which it had lived together with San Marcos University, 2800 Circunvalación Avenue, Lima 41, Peru domestic dogs and cats. At physical examination the 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] 3 [email protected] (corresponding author) cub presented a mild infestation of ectoparasites (ticks and fleas) (Image 1), poor body condition, pallid and yellowish mucous membranes, dehydration, anorexia The Margay, Gato Tigre or Tigrillo Leopardus wiedii, and lethargy; supportive therapy was administered is a small-sized solitary felid which can be found from based on clinical signs. Fleas and ticks were collected southern Texas (USA) to northern Uruguay, mainly directly off the animal and identified as Rhipicephalus occupying forest habitats (Bianchi et al. 2011). It is sanguineus and Ctenocephalides felis by using the classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN Red List and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013) its population is considered to be decreasing (Payan et keys. -

Savannah Cat’ ‘Savannah the Including Serval Hybrids Felis Catus (Domestic Cat), (Serval) and (Serval) Hybrids Of

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Serval hybrids Hybrids of Leptailurus serval (serval) and Felis catus (domestic cat), including the ‘savannah cat’ Anna Markula, Martin Hannan-Jones and Steve Csurhes First published 2009 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: Close-up of a 4-month old F1 Savannah cat. Note the occelli on the back of the relaxed ears, and the tear-stain markings which run down the side of the nose. Photo: Jason Douglas. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Public Domain Licence. Invasive animal risk assessment: Savannah cat Felis catus (hybrid of Leptailurus serval) 2 Contents Introduction 4 Identity of taxa under review 5 Identification of hybrids 8 Description 10 Biology 11 Life history 11 Savannah cat breed history 11 Behaviour 12 Diet 12 Predators and diseases 12 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats (overseas) 13 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats -

Asiatic Golden Cat in Thailand Population & Habitat Viability Assessment

Asiatic Golden Cat in Thailand Population & Habitat Viability Assessment Chonburi, Thailand 5 - 7 September 2005 FINAL REPORT Photos courtesy of Ron Tilson, Sumatran Tiger Conservation Program (golden cat) and Kathy Traylor-Holzer, CBSG (habitat). A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Traylor-Holzer, K., D. Reed, L. Tumbelaka, N. Andayani, C. Yeong, D. Ngoprasert, and P. Duengkae (eds.). 2005. Asiatic Golden Cat in Thailand Population and Habitat Viability Assessment: Final Report. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN. IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © Copyright CBSG 2005 Additional copies of Asiatic Golden Cat of Thailand Population and Habitat Viability Assessment can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124, USA (www.cbsg.org). The CBSG Conservation Council These generous contributors make the work of CBSG possible Providers $50,000 and above Paignton Zoo Emporia Zoo Parco Natura Viva - Italy Laurie Bingaman Lackey Chicago Zoological Society Perth Zoo Lee Richardson Zoo -Chairman Sponsor Philadelphia Zoo Montgomery Zoo SeaWorld, Inc. -

Flat Headed Cat Andean Mountain Cat Discover the World's 33 Small

Meet the Small Cats Discover the world’s 33 small cat species, found on 5 of the globe’s 7 continents. AMERICAS Weight Diet AFRICA Weight Diet 4kg; 8 lbs Andean Mountain Cat African Golden Cat 6-16 kg; 13-35 lbs Leopardus jacobita (single male) Caracal aurata Bobcat 4-18 kg; 9-39 lbs African Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Lynx rufus Felis lybica Canadian Lynx 5-17 kg; 11-37 lbs Black Footed Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Lynx canadensis Felis nigripes Georoys' Cat 3-7 kg; 7-15 lbs Caracal 7-26 kg; 16-57 lbs Leopardus georoyi Caracal caracal Güiña 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Sand Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus guigna Felis margarita Jaguarundi 4-7 kg; 9-15 lbs Serval 6-18 kg; 13-39 lbs Herpailurus yagouaroundi Leptailurus serval Margay 3-4 kg; 7-9 lbs Leopardus wiedii EUROPE Weight Diet Ocelot 7-18 kg; 16-39 lbs Leopardus pardalis Eurasian Lynx 13-29 kg; 29-64 lbs Lynx lynx Oncilla 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus tigrinus European Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Felis silvestris Pampas Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus colocola Iberian Lynx 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Lynx pardinus Southern Tigrina 1-3 kg; 2-6 lbs Leopardus guttulus ASIA Weight Diet Weight Diet Asian Golden Cat 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Leopard Cat 1-7 kg; 2-15 lbs Catopuma temminckii Prionailurus bengalensis 2 kg; 4 lbs Bornean Bay Cat Marbled Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Pardofelis badia (emaciated female) Pardofelis marmorata Chinese Mountain Cat 7-9 kg; 16-19 lbs Pallas's Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Felis bieti Otocolobus manul Fishing Cat 6-16 kg; 14-35 lbs Rusty-Spotted Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Prionailurus viverrinus Prionailurus rubiginosus Flat -

Telling Apart Felidae and Ursidae from the Distribution of Nucleotides in Mitochondrial DNA

Telling apart Felidae and Ursidae from the distribution of nucleotides in mitochondrial DNA Andrij Rovenchak Department for Theoretical Physics, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, 12 Drahomanov St., Lviv, UA-79005, Ukraine [email protected] February 9, 2018 Abstract Rank{frequency distributions of nucleotide sequences in mitochon- drial DNA are defined in a way analogous to the linguistic approach, with the highest-frequent nucleobase serving as a whitespace. For such sequences, entropy and mean length are calculated. These pa- rameters are shown to discriminate the species of the Felidae (cats) and Ursidae (bears) families. From purely numerical values we are able to see in particular that giant pandas are bears while koalas are not. The observed linear relation between the parameters is explained using a simple probabilistic model. The approach based on the non- additive generalization of the Bose-distribution is used to analyze the arXiv:1802.02610v1 [q-bio.OT] 7 Feb 2018 frequency spectra of the nucleotide sequences. In this case, the sepa- ration of families is not very sharp. Nevertheless, the distributions for Felidae have on average longer tails comparing to Ursidae Key words: Complex systems; rank{frequency distributions; mito- chondrial DNA. PACS numbers: 89.20.-a; 87.18.-h; 87.14.G-; 87.16.Tb 1 1 Introduction Approaches of statistical physics proved to be efficient tools for studies of systems of different nature containing many interacting agents. Applications cover a vast variety of subjects, from voting models,1, 2 language dynamics,3, 4 and wealth distribution5 to dynamics of infection spreading6 and cellular growth.7 Studies of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and genomes are of particular in- terest as they can bridge several scientific domains, namely, biology, physics, and linguistics.8{12 Such an interdisciplinary nature of the problem might require a brief introductory information as provided below. -

Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species

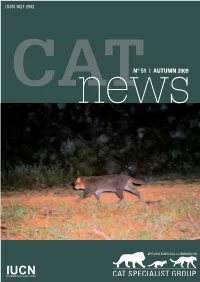

ISSN 1027-2992 CATnewsN° 51 | AUTUMN 2009 01 IUCNThe WorldCATnews Conservation 51Union Autumn 2009 news from around the world KRISTIN NOWELL1 Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species The IUCN Red List is the most authoritative lists participating in the assessment pro- global index to biodiversity status and is the cess. Distribution maps were updated and flagship product of the IUCN Species Survi- for the first time are being included on the val Commission and its supporting partners. Red List website (www.iucnredlist.org). Tex- As part of a recent multi-year effort to re- tual species accounts were also completely assess all mammalian species, the family re-written. A number of subspecies have Felidae was comprehensively re-evaluated been included, although a comprehensive in 2007-2008. A workshop was held at the evaluation was not possible (Nowell et al Oxford Felid Biology and Conservation Con- 2007). The 2008 Red List was launched at The fishing cat is one of the two species ference (Nowell et al. 2007), and follow-up IUCN’s World Conservation Congress in Bar- that had to be uplisted to Endangered by email with others led to over 70 specia- celona, Spain, and since then small changes (Photo A. Sliwa). Table 1. Felid species on the 2009 Red List. CATEGORY Common name Scientific name Criteria CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus C2a(i) ENDANGERED (EN) Andean cat Leopardus jacobita C2a(i) Tiger Panthera tigris A2bcd, A4bcd, C1, C2a(i) Snow leopard Panthera uncia C1 Borneo bay cat Pardofelis badia C1 Flat-headed -

Density Estimation of Asian Bears Using Photographic Capture– Recapture Sampling Based on Chest Marks

Density estimation of Asian bears using photographic capture– recapture sampling based on chest marks Dusit Ngoprasert1,5, David H. Reed2, Robert Steinmetz3, and George A. Gale4 1Conservation Ecology Program, School of Bioresources and Technology, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Bangkok, 10150, Thailand 2Department of Biology, The University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292, USA 3World Wide Fund for Nature–Thailand Office, Bangkok, 10900, Thailand 4Conservation Ecology Program, School of Bioresources and Technology, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Bangkok, 10150, Thailand Abstract: Assessing the conservation status of species of concern is greatly aided by unbiased estimates of population size. Population size is one of the primary parameters determining urgency of conservation action, and it provides baseline data against which to measure progress toward recovery. Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus) and sun bears (Helarctos malayanus) are vulnerable to extinction, but no statistically rigorous population density estimates exist for wild bears of either species. We used a camera-based approach to estimate density of these sympatric bear species. First, we tested a technique to photograph bear chest marks using 3 camera traps mounted on trees facing each other in a triangular arrangement with bait in the center. Second, we developed criteria to identify individual sun bears and black bears based on chest-mark patterns and tested the level of congruence among 5 independent observers using a set of 234 photographs. Finally, we camera-trapped wild bears at 2 study areas (Khlong E-Tow, 33 km2, and Khlong Samor-Pun, 40 km2) in Khao Yai National Park, Thailand, and used chest marks to identify individual bears and thereby derive capture histories for bears of each species. -

The Red Fox Applied Animal Behaviour Science

Author's personal copy Applied Animal Behaviour Science 116 (2009) 260–265 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Animal Behaviour Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/applanim Feeding enrichment in an opportunistic carnivore: The red fox Claudia Kistler a,*, Daniel Hegglin b, Hanno Wu¨ rbel c, Barbara Ko¨nig a a Zoologisches Institut, Universita¨tZu¨rich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zu¨rich, Switzerland b SWILD, Urban Ecology & Wildlife Research, Wuhrstrasse 12, CH-8003 Zu¨rich, Switzerland c Division of Animal Welfare and Ethology, Clinical Veterinary Sciences, University of Giessen, D-35392 Giessen, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: In captive carnivores, species-specific behaviour is often restricted by inadequate feeding Received 18 November 2007 regimens. Feeding live prey is not feasible in most places and food delivery is often Received in revised form 9 September 2008 highly predictable in space and time which is considerably different from the situation in Accepted 16 September 2008 the wild. As a result, captive carnivores are often inactive, show little behavioural Available online 4 November 2008 diversity and are prone to behavioural problems such as stereotypic pacing. Using artificial feeding devices to substitute for natural food resources is a way to address these Keywords: problems. In a group of four red fox (Vulpes vulpes), we compared a conventional feeding Environmental enrichment method to four different methods through the use of feeding enrichment that were Feeding enrichment Foraging based on natural foraging strategies of opportunistic carnivores. Feeding enrichments Red fox consisted of electronic feeders delivering food unpredictable in time which were Vulpes vulpes successively combined with one of the three additional treatments: a self-service food Animal welfare box (allowing control over access to food), manually scattering food (unpredictable in Behavioural diversity space), and an electronic dispenser delivering food unpredictably both in space and time. -

International Bear News

International Bear News Quarterly Newsletter of the International Association for Bear Research and Management (IBA) and the IUCN/SSC Bear Specialist Group February 2012 Vol. 21 no. 1 © A. Sapozhnikov Brown bear family near Shemonaiha, East Kazakhstan. Illegal killing is the greatest threat to these bears. Habitat degradation and loss, and displacement from ecotourism are additional threats. To learn more see article on page 27. IBA website: www.bearbiology.org Table of Contents Council News 31 Perpetual Stochasticity for Black Bears in 4 From the President Mexico 5 Research & Conservation Grants 34 Remembering Conservationist Iftikhar Ahmad 36 Bear Specialist Group Coordinating Bear Specialist Group Committee 6 What was the Last Bear to go Extinct? And what does that have to do with Present-day Conservation? Americas 8 Status of Asiatic Black Bears and Sun Bears 37 Assessing Longitudinal Diet Patterns of in Xe Pian National Protected Area, Lao Black Bears in Great Smoky Mountains PDR National Park Using Stable Carbon and 11 First Confirmed Records of Sun Bears Nitrogen Isotopes in Kulen-Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary, 39 A three legged bear in Denali and Research Northern Cambodia Updates from the Interior and Arctic 13 Status and Conservation of Asiatic Black Alaska Bears in Diamer District, Pakistan 40 Recent and Current Bear Studies in Interior 15 First Camera-trap Photos of Asiatic and Arctic Alaska Black Bears in the Bashagard Region of 42 Grizzly Bear Population Study Begins in Southeastern Iran Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem in NW Montana/ -

Freeman AR, Machugh DE, Mckeown S, Walzer C, Mcconnell DJ, Bradley DG

Freeman AR, Machugh DE, McKeown S, Walzer C, McConnell DJ, Bradley DG. 2001. Sequence variation in the mitochondrial DNA control region of wild African cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). Heredity 86:355-62. Keywords: Acinonyx jubatus/cheetah/evolution/Felis silvestris/Felis silvestris catus/gene flow/ genetic variation/genetics/Leopardus pardalis/Leopardus wiedii/margay/mtDNA/Ocelot/research Abstract: Five hundred and twenty-five bp of mitochondrial control region were sequenced and analyzed for 20 Acinonyx jubatus and one Felis catus. These sequences were compared with published sequences from another domestic cat, 20 ocelots (Leopardus pardalis) and 11 margays (Leopardus weidii). The intraspecific population divergence in cheetahs was found to be less than in the other cats. However, variation was present and distinct groups of cheetahs were discernible. The 80 bp RS2 repetitive sequence motif previously described in other felids was found in four copies in cheetah. The repeat units probably have the ability to form secondary structure and may have some function in the regulation of control region replication. The two central repeat units in cheetah show homogenization that may have arisen by convergent evolution. Heredity 86 (2001) 355±362 Received 23 February 2000, accepted 16 November 2000 Sequence variation in the mitochondrial DNA control region of wild African cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) ABIGAIL R. FREEMAN , DAVID E. MACHUGHà, SEAÂ N MCKEOWN**§, CHRISTIAN WALZER±, DAVID J. MCCONNELL § & DANIEL G. BRADLEY* Department of Genetics, Smur®t Institute of Genetics, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland, àDepartment of Animal Science and Production and Conway Institute of Biomolecular and Biomedical Research, Faculty of Agriculture, University College Dublin, Bel®eld, Dublin 4, Ireland, §Fota Wildlife Park, Carraigtwohill, County Cork, Ireland and ±Salzburger Tiergarten Hellbrunn, A-5081 Anif, Austria Five hundred and twenty-®ve bp of mitochondrial control region were sequenced and analysed for 20 Acinonyx jubatus and one Felis catus.