Integration of the North East: the State Formation Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

Understanding the Art and Culture of Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya EK BHARAT SHRESHTHA BHARAT ( ( a CBSE Initiative –Pairing States Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya)

WINTER HOLIDAY HOMEWORK CLASS - 4 Topic- Understanding the Art and Culture of Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya EK BHARAT SHRESHTHA BHARAT ( ( A CBSE initiative –pairing states Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya) Dear Parents Warm greetings! The winter holidays are round the corner and in this era of restricted travelling the predicament of keeping children engaged and still managing work from home is a glaring reality. So, keeping that in mind we bring for our students a fun-filled journey of India’s beautiful North-eastern states from the safety and comfort of our homes. Following the ‘Ek Bharat Shreshtha Bharat’ initiative of CBSE we have designed a series of activities for students that will help them learn and explore about these North-eastern states. The project is a kaleidoscope of simple but thoughtfully-planned activities which will target the critical and creative thinking of the students. It is an integrated project with well-knit curricular and co-curricular activities targeting competency based learning. PLEASE NOTE: These activities will be assessed for Round IV. Students are requested to submit their projects in the following manner through Google Classroom: S.NO SUBJECTS DATE OF SUBMISSION 1. ENG,HINDI 15.01.21 2. MATHS,SCIENCE 18.01.21 3. ICT, SST 19.01.21 4. SPORTS & DANCE 22.01.21 Wish you an elated holiday time and a fantastic year ahead! Introduction Imagine you are on a seven-day tour of Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya. In these seven days, you are visiting Tawang, Ziro Valley, Namdapha Wildlife Sanctuary, Cherrapunji, Shillong, Living Root Bridges and Umiam Lake. -

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Status of Insectivorous Plants in Northeast India

Technical Refereed Contribution Status of insectivorous plants in northeast India Praveen Kumar Verma • Shifting Cultivation Division • Rain Forest Research Institute • Sotai Ali • Deovan • Post Box # 136 • Jorhat 785 001 (Assam) • India • [email protected] Jan Schlauer • Zwischenstr. 11 • 60594 Frankfurt/Main • Germany • [email protected] Krishna Kumar Rawat • CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute • Rana Pratap Marg • Lucknow -226 001 (U.P) • India Krishna Giri • Shifting Cultivation Division • Rain Forest Research Institute • Sotai Ali • Deovan • Post Box #136 • Jorhat 785 001 (Assam) • India Keywords: Biogeography, India, diversity, Red List data. Introduction There are approximately 700 identified species of carnivorous plants placed in 15 genera of nine families of dicotyledonous plants (Albert et al. 1992; Ellison & Gotellli 2001; Fleischmann 2012; Rice 2006) (Table 1). In India, a total of five genera of carnivorous plants are reported with 44 species; viz. Utricularia (38 species), Drosera (3), Nepenthes (1), Pinguicula (1), and Aldrovanda (1) (Santapau & Henry 1976; Anonymous 1988; Singh & Sanjappa 2011; Zaman et al. 2011; Kamble et al. 2012). Inter- estingly, northeastern India is the home of all five insectivorous genera, namely Nepenthes (com- monly known as tropical pitcher plant), Drosera (sundew), Utricularia (bladderwort), Aldrovanda (waterwheel plant), and Pinguicula (butterwort) with a total of 21 species. The area also hosts the “ancestral false carnivorous” plant Plumbago zelayanica, often known as murderous plant. Climate Lowland to mid-altitude areas are characterized by subtropical climate (Table 2) with maximum temperatures and maximum precipitation (monsoon) in summer, i.e., May to September (in some places the highest temperatures are reached already in April), and average temperatures usually not dropping below 0°C in winter. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

UNICEF Support to the COVID-19 Surge in India As Part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A)

UNICEF support to the COVID-19 surge in India as part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) The reach and capacity of the cold chain system in India is strengthened to sustain the massive COVID- 19 vaccine drive • UNICEF has worked at the request of MoHFW to augment the cold chain network across the country since third quarter of 2020. In preparation of the launch of vaccination drive, additional cold chain equipment, such as a Walk-In Cold Rooms (WIC), Walk-In Freezer Rooms (WIF), fridges and deep freezers were procured to enhance vaccine storage at all levels. Vaccine transportation passive devices (cold box/vaccine carriers) were also procured to support the vaccination rollout. • The vaccine rollout was launched nationwide on the 16th of January 2021, with priority to Health Care Workers, Frontline Workers and people aged 60 years and above. On 1st April 2021, vaccination was made available to those above the age of 45. Over 156 million vaccine doses have been administered as of 1st May 2021, Day 106 of the vaccination campaign, making India the country with the fastest vaccination scale up in the world. • As of May 1st, vaccine eligibility has been expanded to all above the age of 18. With this expansion and to support equitable access to vaccination even in remote areas, UNICEF will/ plans to further augment bulk storage sites by providing additional equipment (WIC/WIF) along with Solar Direct Drive (SDD) Fridges for remote locations with limited power supply. • Current COVID-19 vaccines in use in India are freeze sensitive. -

The Challenge of Peace in Nagaland

India talks with Naga rebels The challenge of peace in Nagaland BY RUPAK CHATTOPADHYAY There are times when the of the most complex. Government of India and armed separatists are not only willing to talk The Nagas before 1975 but to agree on something. That happened on January 31 in Bangkok There are seventeen major and an when both India and one such group, equal number of smaller Naga tribes, the National Socialist Council of each with its own recognizable dialect Nagaland — Isaac Muivah faction, and customs, linked traditionally by a known as NSCN-IM, extended an shared way of life and religious eight-year-old ceasefire for another In New Delhi, the Secretary-General of India's practices, and indeed more recently by six months as both sides attempt to upper house of parliament receives members of Christianity. There are more than 14 find a solution to this long-running the Nagaland Legislative Assembly. tribes that make up the Nagas. Tribal insurgency. conflicts have complicated the process The Naga revolt is centred in the state of Nagaland – one of of peacemaking in the state of seven in North East India. They are known as the “seven Nagaland, and other Naga inhabited areas, over the years. sisters”: Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, Tripura, Meghalaya, Nagas also reside in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram, which are among the Assam and Manipur. most neglected and underdeveloped parts of India. The The Naga rebellion dates back to India’s independence in North East is a remote region connected to the rest of India 1947, when separatist sentiments represented by A. -

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project A preliminary report from the Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) Preliminary Report on the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project November 2009 Copies - 500 Written & Published by Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) P.O Box - 135 Mae Sot Tak - 63110 Thailand Phone: + 66(0)55506618 Emails: [email protected] or [email protected] www.arakanrivers.net Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary …………………………………......................... 1 2. Technical Specifications ………………………………...................... 1 2.1. Development Overview…………………….............................. 1 2.2. Construction Stages…………………….................................... 2 3. Companies and Authorities Involved …………………....................... 3 4. Finance ………………………………………………......................... 3 4.1. Projected Costs........................................................................... 3 4.2. Who will pay? ........................................................................... 4 5. Who will use it? ………………………………………....................... 4 6. Concerns ………………………………………………...................... 4 6.1. Devastation of Local Livelihoods.............................................. 4 6.2. Human rights.............................................................................. 7 6.3. Environmental Damage............................................................. 10 7. India- Burma (Myanmar) Relations...................................................... 19 8. Our Aims and Recommendations to the media................................... -

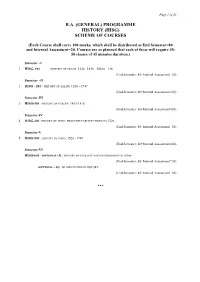

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Histrical Background Changlang District Covered with Picturesque Hills Lies in the South-Eastern Corner of Arunachal Pradesh, Northeast India

Histrical Background Changlang District covered with picturesque hills lies in the south-eastern corner of Arunachal Pradesh, northeast India. It has an area of 4,662 sqr. Km and a population of 1,48,226 persons as per 2011 Census. According to legend the name Changlang owes its origin to the local word CHANGLANGKAN which means a hilltop where people discovered the poisonous herb, which is used for poisoning fish in the river. Changlang District has reached the stage in its present set up through a gradual development of Administration. Prior to 14th November 1987, it was a part of Tirap District. Under the Arunachal Pradesh Reorganization of Districts Amendment Bill, 1987,the Government of Arunachal Pradesh, formally declared the area as a new District on 14th November 1987 and became 10th district of Arunachal Pradesh. The legacy of Second World War, the historic Stilwell Road (Ledo Road), which was constructed during the Second World War by the Allied Soldiers from Ledo in Assam, India to Kunming, China via hills and valleys of impenetrable forests of north Burma (Myanmar) which section of this road is also passed through Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh and remnant of Second World War Cemetery one can see at Jairampur – Nampong road. Location and Boundary The District lies between the Latitudes 26°40’N and 27°40’N, and Longitudes 95°11’E and 97°11’E .It is bounded by Tinsukia District of Assam and Lohit District of Arunachal Pradesh in the north, by Tirap District in the west and by Myanmar in the south-east. -

The State and Identities in NE India

1 Working Paper no.79 EXPLAINING MANIPUR’S BREAKDOWN AND MANIPUR’S PEACE: THE STATE AND IDENTITIES IN NORTH EAST INDIA M. Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE February 2006 Copyright © M.Sajjad Hassan, 2006 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Development Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. 1 Crisis States Programme Explaining Manipur’s Breakdown and Mizoram’s Peace: the State and Identities in North East India M.Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE Abstract Material from North East India provides clues to explain both state breakdown as well as its avoidance. They point to the particular historical trajectory of interaction of state-making leaders and other social forces, and the divergent authority structure that took shape, as underpinning this difference. In Manipur, where social forces retained their authority, the state’s autonomy was compromised. This affected its capacity, including that to resolve group conflicts. Here powerful social forces politicized their narrow identities to capture state power, leading to competitive mobilisation and conflicts. -

The Spectre of SARS-Cov-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: a Tale of Two Cities

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . The Spectre of SARS-CoV-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: A Tale of Two Cities Manish Kumar1,2*, Payal Mazumder3, Jyoti Prakash Deka4, Vaibhav Srivastava1, Chandan Mahanta5, Ritusmita Goswami6, Shilangi Gupta7, Madhvi Joshi7, AL. Ramanathan8 1Discipline of Earth Science, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 355, India 2Kiran C Patel Centre for Sustainable Development, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 3Centre for the Environment, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 4Discipline of Environmental Sciences, Gauhati Commerce College, Guwahati, Assam 781021, India 5Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 6Tata Institute of Social Science, Guwahati, Assam 781012, India 7Gujarat Biotechnology Research Centre (GBRC), Sector- 11, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 011, India 8School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected]; [email protected] Manish Kumar | Ph.D, FRSC, JSPS, WARI+91 863-814-7602 | Discipline of Earth Science | IIT Gandhinagar | India 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021.