Tracey Emin: Life Made Art, Art Made from Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Rose Wylie 'Tilt the Horizontal Into a Slant'

Rose Wylie Tilt The Horizontal Into A Slant 4 TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT 5 INTRO Rose Wylie’s pictures are bold, occasionally chaotic, often unpredictable, and always fiercely independent, without being domineering. Wylie works directly on to large unprimed, unstretched canvases and her inspiration comes from many and varied sources, most of them popular and vernacular. The cutout techniques of collage and the framing devices of film, cartoon strips and Renaissance panels inform her compositions and repeated motifs. Often working from memory, she distils her subjects into succinct observations, using text to give additional emphasis to her recollections. Wylie borrows from first-hand imagery of her everyday life as well as films, newspapers, magazines, and television allowing herself to follow loosely associated trains of thought, often in the initial form of drawings on paper. The ensuing paintings are spontaneous but carefully considered: mixing up ideas and feelings from both external and personal worlds. Rose Wylie favours the particular, not the general; although subjects and meaning are important, the act of focused looking is even more so. Every image is rooted in a specific moment of attention, and while her work is contemporary in terms of its fragmentation and cultural references, it is perhaps more traditional in its commitment to the most fundamental aspects of picturemaking: drawing, colour, and texture. 8 TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT 9 COMING UNSTUCK the power zing back and forth between the painting and us, the viewer? It’s both elegant It may come as a surprise to some, when and inelegant but never either ‘quirky’ or considering Wylie’s work that words like ‘power’ ‘goofy’. -

TURNER PRIZE: Most Prestigious— Yet Also Controversial

TURNER PRIZE: Most prestigious— yet also controversial Since its inception, the Turner Prize has been synonymous with new British art – and with lively debate. For while the prize has helped to build the careers of a great many young British artists, it has also generated controversy. Yet it has survived endless media attacks, changes of terms and sponsor, and even a year of suspension, to arrive at its current status as one of the most significant contemporary art awards in the world. How has this controversial event shaped the development of British art? What has been its role in transforming the new art being made in Britain into an essential part of the country’s cultural landscape? The Beginning The Turner Prize was set up in 1984 by the Patrons of New Art (PNA), a group of Tate Gallery benefactors committed to raising the profile of contemporary art. 1 The prize was to be awarded each year to “the person who, in the opinion of the jury, has made the greatest contribution to art in Britain in the previous twelve months”. Shortlisted artists would present a selection of their works in an exhibition at the Tate Gallery. The brainchild of Tate Gallery director Alan Bowness, the prize was conceived with the explicit aim of stimulating public interest in contemporary art, and promoting contemporary British artists through broadening the audience base. At that time, few people were interested in contemporary art. It rarely featured in non-specialist publications, let alone in the everyday conversations of ordinary members of the public. The Turner Prize was named after the famous British painter J. -

Anya Gallaccio

ANYA GALLACCIO Born Paisley, Scotland 1963 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom 1988 Goldsmiths' College, University of London, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 NOW, The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland Stroke, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2018 dreamed about the flowers that hide from the light, Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, United Kingdom All the rest is silence, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom 2017 Beautiful Minds, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2015 Silas Marder Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA 2014 Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Saxmundham, Suffolk, United Kingdom Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2013 ArtPace, San Antonio, TX 2011 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland, Kilmarnock, United Kingdom Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2009 So Blue Coat, Liverpool, United Kingdom 2008 Camden Art Centre, London, United Kingdom 2007 Three Sheets to the wind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2006 Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil One art, Sculpture Center, New York, NY 2005 The Look of Things, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA Silver Seed, Mount Stuart Trust, Isle of Bute, Scotland 2004 Love is Only a Feeling, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2003 Love is only a feeling, Turner Prize Exhibition, -

PRESS RELEASE Los Angeles Collectors Jane and Marc

PRESS RELEASE Los Angeles Collectors Jane and Marc Nathanson Give Major Artworks to LACMA Art Will Be Shown with Other Promised Gifts at 50th Anniversary Exhibition in April (Image captions on page 3) (Los Angeles, January 26, 2015)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is pleased to announce eight promised gifts of art from Jane and Marc Nathanson. The Nathansons’ gift of eight works of contemporary art includes seminal pieces by Damien Hirst, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and others. The bequest is made in honor of LACMA’s 50th anniversary in 2015. The gifts kick off a campaign, chaired by LACMA trustees Jane Nathanson and Lynda Resnick, to encourage additional promised gifts of art for the museum’s anniversary. Gifts resulting from this campaign will be exhibited at LACMA April 26–September 7, 2015, in an exhibition, 50 for 50: Gifts on the Occasion of LACMA’s Anniversary. "What do you give a museum for its birthday? Art. As we reach the milestone of our 50th anniversary, it is truly inspiring to see generous patrons thinking about the future generations of visitors who will enjoy these great works of art for years and decades to come,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “Jane and Marc Nathanson have kicked off our anniversary year in grand fashion.” Jane Nathanson added, “I hope these gifts will inspire others to make significant contributions in the form of artwork as we look forward not only to the 50th anniversary of the museum, but to the next 50 years. -

Art, Real Places, Better Than Real Places 1 Mark Pimlott

Art, real places, better than real places 1 Mark Pimlott 02 05 2013 Bluecoat Liverpool I/ Many years ago, toward the end of the 1980s, the architect Tony Fretton and I went on lots of walks, looking at ordinary buildings and interiors in London. When I say ordinary, they had appearances that could be described as fusing expediency, minimal composition and unconscious newness. The ‘unconscious’ modern architecture of the 1960s in the city were particularly interesting, as were places that were similarly, ‘unconsciously’ beautiful. We were the ones that were conscious of their raw, expressive beauty, and the basis of this beauty lay in the work of minimal and conceptual artists of that precious period between 1965 and 1975, particularly American artists, such as Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Dan Flavin and Dan Graham. It was Tony who introduced (or re-introduced) me to these artists: I had a strong memory of Minimal Art from visits to the National Gallery in Ottawa, and works of Donald Judd, Claes Oldenburg and Richard Artschwager as a child. There was an aspect of directness, physicality, artistry and individualized or collective consciousness about this work that made it very exciting to us. This is the kind of architecture we wanted to make; and in my case, this is how I wanted to see, make pictures and make environments. To these ends, we made trips to see a lot of art, and art spaces, and the contemporary art spaces in Germany and Switzerland in particular held a special significance for us. I have to say that very few architects in Britain were doing this at the time, or looking at things the way we looked at them. -

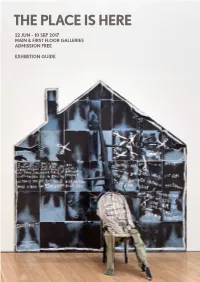

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Artist of the Day 2016 F: +44 (0)20 7439 7733

PRESS RELEASE T: +44 (0)20 7439 7766 ARTIST OF THE DAY 2016 F: +44 (0)20 7439 7733 21 Cork Street 20 June - 2 July 2016 London W1S 3LZ Monday - Friday 11am - 7pm [email protected] Saturday - 11am - 6pm www.flowersgallery.com Flowers Gallery is pleased to announce the 23rd edition of Artist of the Day, a valuable platform for emerging artists since 1983. The two-week exhibition showcases the work of ten artists, nominated by prominent figures in contemporary art. The criteria for selection is talent, originality, promise and the ability to benefit from a one-day solo exhibition of their work at Flowers Gallery, Cork Street. “Every year we look forward to encountering the unknown and unpredictable. The constraint of time to install and promote an exhibition for one day only ensures there is a tangible energy in the gallery, with each day’s show incomparable to the other days. Artist of the Day has given a platform and context to artists who may not have exhibited much before, accompanied by the support and dedication of their selectors. The relationship between the selector and the artist adds an intimate power to the installations, and as a gallery we have gone on to work with many of the selected artists long term.” – Matthew Flowers Past selectors have included Patrick Caulfield, Helen Chadwick, Jake & Dinos Chapman, Tracey Emin, Gilbert & George, Maggi Hambling, Albert Irvin, Cornelia Parker, Bridget Riley and Gavin Turk; while Billy Childish, Adam Dant, Dexter Dalwood, Nicola Hicks, Claerwen James and Seba Kurtis, Untitled, 2015, Lambda C-Type print Lynette Yiadom-Boakye have featured as chosen artists. -

Press Release

Press Release Abigail Lane Tomorrows World, Yesterdays Fever (Mental Guests Incorporated) Victoria Miro Gallery, 4 October – 10 November 2001 The exhibition is organized by the Milton Keynes Gallery in collaboration with Film and Video Umbrella The Victoria Miro Gallery presents a major solo exhibition of work by Abigail Lane. Tomorrows World, Yesterdays Fever (Mental Guests Incorporated) extends her preoccupation with the fantastical, the Gothic and the uncanny through a trio of arresting and theatrical installations which are based around film projections. Abigail Lane is well known for her large-scale inkpads, wallpaper made with body prints, wax casts of body fragments and ambiguous installations. In these earlier works Lane emphasized the physical marking of the body, often referred to as traces or evidence. In this exhibition Lane turns inward giving form to the illusive and intangible world of the psyche. Coupled with her long-standing fascination with turn-of-the-century phenomena such as séances, freak shows, circus and magic acts, Lane creates a “funhouse-mirror reflection” of the life of the mind. The Figment explores the existence of instinctual urges that lie deep within us. Bathed in a vivid red light, the impish boy-figment beckons us, “Hey, do you hear me…I’m inside you, I’m yours…..I’m here, always here in the dark, I am the dark, your dark… and I want to play….”. A mischievous but not sinister “devil on your shoulder” who taunts and tempts us to join him in his wicked game. The female protagonist of The Inclination is almost the boy-figment’s antithesis. -

Shock Value: the COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR?

Shock Value: THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? BY REENA JANA SHOCK VALUE: enough to prompt San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker to state, “I THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? don’t know another private collection as heavy on ‘shock art’ as Logan’s is.” When asked why his tastes veer toward the blatantly gory or overtly sexual, Logan doesn’t attempt to deny that he’s interested in shock art. But he does use predictably general terms to “defend” his collection, as if aware that such a collecting strategy may need a defense. “I have always sought out art that faces contemporary issues,” he says. “The nature of contemporary art is that it isn’t necessarily pretty.” In other words, collecting habits like Logan’s reflect the old idea of le bourgeoisie needing a little épatement. Logan likes to draw a line between his tastes and what he believes are those of the status quo. “The majority of people in general like to see pretty things when they think of what art should be. But I believe there is a better dialogue when work is unpretty,” he says. “To my mind, art doesn’t fulfill its function unless there’s ent Logan is burly, clean-cut a dialogue started.” 82 and grey-haired—the farthestK thing you could imagine from a gold-chain- Indeed, if shock art can be defined, it’s art that produces a visceral, 83 wearing sleazeball or a death-obsessed goth. In fact, the 57-year-old usually often unpleasant, reaction, a reaction that prompts people to talk, even if at sports a preppy coat and tie. -

Art and Design Advanced Unit 4: A2 Externally Set Assignment

Pearson Edexcel GCE Art and Design Advanced Unit 4: A2 Externally Set Assignment Timed Examination: 12 hours Paper Reference 6AD04-6CC04 You do not need any other materials. Instructions to Teacher-Examiners Centres will receive this paper in January 2016. It will also be available on the secure content section of the Pearson Edexcel website at this time. This paper should be given to the Teacher–Examiner for confidential reference as soon as it is received in the centre in order to prepare for the externally set assignment. This paper may be released to candidates from 1 February 2016. There is no prescribed time limit for the preparatory study period. The 12-hour timed examination should be the culmination of candidates’ studies. Instructions to Candidates This paper is given to you in advance of the examination so that you can make sufficient preparation. This booklet contains the theme for the Unit 4 Externally Set Assignment for the following specifications: 9AD01 Art, Craft and Design (unendorsed) 9FA01 Fine Art 9TD01 Three-Dimensional Design 9PY01 Photography – Lens and Light-Based Media 9TE01 Textile Design 9GC01 Graphic Communication 9CC01 Critical and Contextual Studies Candidates for all endorsements are advised to read the entire paper. Turn over P46723A ©2016 Pearson Education Ltd. *P46723A* 1/1/1/1/1/1/c2 Each submission for the A2 Externally Set Assignment, whether unendorsed or endorsed, should be based on the theme given in this paper. You are advised to read through the entire paper, as helpful starting points may be found outside your chosen endorsement. If you are entered for an endorsed specification, you should produce work predominantly in your chosen discipline for the Externally Set Assignment. -

Art REVOLUTIONARIES Six Years Ago, Two Formidable, Fashionable Women Launched a New Enterprise

Art rEVOLUtIONArIES SIx yEArS AgO, twO fOrmIdAbLE, fAShIONAbLE wOmEN LAUNchEd A NEw ENtErprISE. thEIr mISSION wAS tO trANSfOrm thE wAy wE SUppOrt thE ArtS. thEIr OUtSEt/ frIEzE Art fAIr fUNd brOUght tOgEthEr pAtrONS, gALLErIStS, cUrAtOrS, thE wOrLd’S grEAtESt cONtEmpOrAry Art fAIr ANd thE tAtE IN A whIrLwINd Of fUNdrAISINg, tOUrS ANd pArtIES, thE LIkES Of whIch hAd NEVEr bEEN SEEN bEfOrE. hErE, fOr thE fIrSt tImE, IS thEIr INSIdE StOry. just a decade ago, the support mechanism for young artists in Britain was across the globe, and purchase it for the Tate collection, with the Outset funds. almost non-existent. Government funding for purchases of contemporary art It was a winner all round. Artists who might never have been recognised had all but dried up. There was a handful of collectors but a paucity of by the Tate were suddenly propelled into recognition; the national collection patronage. Moreover, patronage was often an unrewarding experience, both acquired work it would never otherwise have afforded. for the donor and for the recipient institution. Mechanisms were brittle and But the masterstroke of founders Gertler and Peel was that they made it old-fashioned. Artists were caught in the middle. all fun. Patrons were whisked on tours of galleries around the world or to Then two bright, brisk women – Candida Gertler and Yana Peel – marched drink champagne with artists; galleries were persuaded to hold parties into the picture. They knew about art; they had broad social contacts across a featuring collections of work including those by (gasp) artists tied to other new generation of young wealthy; and they had a plan.