Patricia Fraser Dissertation FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Autobiographies: Psychoanalysis and the Graphic Novel

AUTOBIOGRAPHIES: PSYCHOANALYSIS AND THE GRAPHIC NOVEL PARASKEVI LYKOU PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JANUARY 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the conjunction of the graphic novel with life- writing using psychoanalytic concepts, primarily Freudian and post- Freudian psychoanalysis, to show how the graphic medium is used to produce a narrative which reconstructs the function of the unconscious through language. The visual language is rich in meaning, with high representational potential which results in a vivid representation of the unconscious, a more or less raw depiction of the function of the psychoanalytic principles. In this project I research how life-writing utilises the unique representational features of the medium to uncover dimensions of the internal-self, the unconscious and the psyche. I use the tools and principles of psychoanalysis as this has been formed from Freud on and through the modern era, to propose that the visual language of the graphic medium renders the unconscious more accessible presenting the unconscious functionality in a uniquely transparent way, so that to some extent we can see parts of the process of the construction of self identity. The key texts comprise a sample of internationally published, contemporary autobiographical and biographical accounts presented in the form of the graphic novel. The major criterion for including each of the novels in my thesis is that they all are, in one way or another, stories of growing up stigmatised by a significant trauma, caused by the immediate familial and/or social environment. Thus they all are examples of individuals incorporating the trauma in order to overcome it, and all are narrations of constructing a personal identity through and because of this procedure. -

GULDEN-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.359Mb)

A Stage Full of Trees and Sky: Analyzing Representations of Nature on the New York Stage, 1905 – 2012 by Leslie S. Gulden, M.F.A. A Dissertation In Fine Arts Major in Theatre, Minor in English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Dorothy Chansky Chair of Committee Dr. Sarah Johnson Andrea Bilkey Dr. Jorgelina Orfila Dr. Michael Borshuk Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leslie S. Gulden Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to my Dissertation Committee Chair and mentor, Dr. Dorothy Chansky, whose encouragement, guidance, and support has been invaluable. I would also like to thank all my Dissertation Committee Members: Dr. Sarah Johnson, Andrea Bilkey, Dr. Jorgelina Orfila, and Dr. Michael Borshuk. This dissertation would not have been possible without the cheerleading and assistance of my colleague at York College of PA, Kim Fahle Peck, who served as an early draft reader and advisor. I wish to acknowledge the love and support of my partner, Wesley Hannon, who encouraged me at every step in the process. I would like to dedicate this dissertation in loving memory of my mother, Evelyn Novinger Gulden, whose last Christmas gift to me of a massive dictionary has been a constant reminder that she helped me start this journey and was my angel at every step along the way. Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………ii ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………..………………...iv LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………..v I. -

MSA Conference Warsaw 2021

Print Day 1, Jul 05, 2021 12:30PM - 02:00PM Opening event of cultural program: Exhibition of Works by Wilhelm Sasnal “Such a Landscape” in the POLIN Museum of Polish Jews, guided by Luiza Nader Plenary Session Moderators Katarzyna Chmielewska, PHD; Assistant Professor, Institute Of Literary Research Of The Polish Academy Of Sciences (IBL PAN) Opening event of cultural program Exhibition of Works by Wilhelm Sasnal "Such a Landscape" in the POLIN Museum of Polish Jews, guided by Luiza NaderChair: Katarzyna Chmielewska, Paweł Dobrosielski 02:00PM - 03:00PM Welcome to the 5th Annual MSA Conference in Warsaw Plenary Session Speakers Aline Sierp, Assistant Professor In European Studies, Maastricht University Jenny Wustenberg, Associate Professor, Nottingham Trent University Je!rey Olick, Professor, University Of Virginia Welcome Je!rey Olick, Aline Sierp & Jenny Wüstenberg (co-presidents MSA); institutional representatives (local organizers MSA 2021) 03:00PM - 05:00PM Embattled histories: changing patterns of historical culture across East Central Europe Track : Roundtable Sub-plenary session 1 Speakers Zoltan Dujisin, FSR Incoming Postdoc, UCLouvain James Mark, Professor, University Of Exeter Ana MILOSEVIC, Post Doc, KU Leuven Dariusz Stola, Professor, ISP PAN Eva-Clarita Pettai, Senior Research Associate, Imre Kertész Kolleg, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena Moderators Joanna Wawrzyniak, Dr Hab, University Of Warsaw The history of the 20th century remains highly contested across East Central and Southeastern Europe (ECSE). Thirty years after the end of state socialism, an open public discourse and the free interaction between producers and consumers of historical culture continues to be an embattled public good. Especially over the past decade, it has been increasingly challenged by economic and administrative constrains, but most of all by ideological and legislative interventions that aimed at determining what people can learn about, and how they make sense of historical legacies and meanings. -

Downloading Grief: Minority Populations Mourn Diana’, in Steinberg, D

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/50750 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Mourning Identities: Hillsborough, Diana and the Production of Meaning by Michael J. Brennan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick Department of Sociology September 2003 Contents Introduction 1 Shifting Focus, Shifting Orientation 1 Biography of the Project 2 The Hillsborough Disaster and the Death of Princess Diana 7 The Inter-Disciplinary and Multi-Method Approach of the Project 10 Outline of the Chapters 16 Chapter 1: Approaches to Death, Dying and Bereavement 22 The Denial and Revival of death 26 Death and Contemporary Social Theory 33 Death Studies: Academic Specialism or Thanatological Ghetto 47 Towards the ‘Sociological Private’ 54 Chapter 2: Mourning, Identity and the Work of the Unconscious 60 The Scandal of Reason: Freud’s Copernican Revolution 65 Misogyny and Medical Discourse: Feminist Critiques of Freud 71 Mortido Destrudo: Freud’s Detour of Theory From Eros to Thanatos 74 Mourning, Loss and the Work of Mourning 82 Kleinian Object-Relations and the Internalisation of ‘Things’ 94 Kristeva and -

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP a AC/DC HIGH VOLTAGE 1975 ATL 50257 GER LP Debuten Til Hardrocker'ne Fra Down Under

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP A AC/DC HIGH VOLTAGE 1975 ATL 50257 GER LP Debuten til hardrocker'ne fra Down Under. AC/DC POWERAGE 1978 ATL 50483 FRA LP 6.albumet i rekken av mange utgivelser. ACKLES, DAVID AMERICAN GOTHIC 1972 EKS-75032 USA LP Strålende låtskriver, albumet produsert av Bernie Taupin, kompisen til Elton John. AEROSMITH PUMP 1989 GEFFEN REC924254 USA LP 1982 Fengende synthpop/new wave fra flinke gutter med sær frisyre. Produsert av Bill Nelson A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS HOP 201 UK LP (Be Bop Deluxe) AFZELIUS & WIEHE AFZELIUS & WIEHE 1986 TRAM 70 SWE LP Flott låtskriverpar,her med god hjelp av bl.a Marius Muller. AKKERMAN, JAN JAN AKKERMAN 1977 ATL 50420 HOL LP Soloalbum fra den glimrende gitaristen fra nederlandske Focus. AKKERMAN, JAN & CLAUS OGERMAN ARANJUEZ 1978 CBS 81843 HOL LP Jazz / klassisk fra gitaristen fra Focus,med arrangør og dirigent Claus Ogerman ALAN PARSONS PROJECT, THE TALES OF MYSTERY AND IMAGINATION 1976 20TH CENT. FOX SPA LP Spansk LP utgivelse, basert på tekster av Edgar Allan Poe.Hipgnosis cover. ALAN PARSONS PROJECT, THE I ROBOT 1978 ARTISTA 062-99168 SWE LP Coverdesign av Hipgnosis En av de beste med Alan P., med tysk symf.orkester,vocalhjelp fra Leslie Duncan, Clare 1979 Torry (P:Floyd), hun med den utrolige bra vocalen i Great gig in the sky (Dark side of the ALAN PARSONS PROJECT, THE EVE ARTISTA 201 157 HOL LP moon). 1980 Hjelp av Elmer Ganrtry (Velvet Opera) på vocal.Tysk symf.orch.Cover av K.Godley & ALAN PARSONS PROJECT, THE THE TURN OF A FRIENDLY CARD ARTISTA I-203000 SPA LP L.Creme 1983 ALAN PARSONS PROJECT, THE THE BEST OF ALAN PARSONS PROJECT ARI 90066 HOL LP Alan Parson,produsent og tekniker fra Dark side of the moon med Pink Floyd. -

A Fountain for Memory

1 A FOUNTAIN FOR MEMORY: The Trevi Flow of Power and Transcultural Performance Pam Krist, PhD Thesis School of Modern Languages, Literature and Culture Royal Holloway, University of London 2015 2 3 Abstract In memory studies much research on monuments focuses on those with traumatic or controversial associations whilst others can be overlooked. The thesis explores this gap and seeks to supplement the critical understanding of a populist monument as a nexus for cultural remembering. The Trevi Fountain in Rome is chosen because it is a conduit for the flow of multivalent imagery, ideological manipulation, and ever-evolving performances of memory, from design plans to mediated representations. The thesis begins by locating the historical pre-material and material presences of the Fountain, establishing this contextual consideration as contributory to memory studies. It then surveys the field of theory to build a necessarily flexible conceptual framework for researching the Fountain which, given the movement and sound of water and the coin-throwing ritual, differs from a static monument in its memorial connotations. The interpretations of the illusory Trevi design and its myths are explored before employing a cross-disciplinary approach to the intertextuality of its presences and its performative potential in art, literature, film, music, advertising and on the Internet. The thesis concludes with questions about the digital Trevi and dilution of memory. Gathering strength throughout is the premise of the Fountain as a transcultural vehicle for dominant ideologies ‒ from the papal to commercial, the Grand Tour to cyber tourism ‒ seeking to control remembering and forgetting. Sometimes these are undermined by the social and inventive practices of memory. -

View. Theories and Practices of Visual Culture

25 View. Theories and Practices of Visual Culture title: Necrocartography: Topographies and topologies of dispersed Shoah authors: Aleksandra Szczepan, Kinga Siewior source: View. Theories and Practices of Visual Culture 25 (2019) URL: https://www.pismowidok.org/en/archive/2019/25-present- history/necrocartography doi: https://doi.org/10.36854/widok/2019.25.2065 publisher: Widok. Foundation for Visual Culture affiliation: The Polish National Film, Television and Theatre School in Lodz Institute of Polish Culture, University of Warsaw The Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences 1 / 58 Aleksandra Szczepan et al. Necrocartography keywords: Holocaust; map; topology; topography; cartography; testimony; cultural geography abstract: On the basis of the experience of spatial confusion and inadequacy, common during visits at uncommemorated sites of violence, the authors propose to expand the topological reflection in the research on the spatialities of the Holocaust, as well as to introduce topology to the analysis of the everyday experiences of users of the post-genocidal space of Central and Eastern Europe’s bloodlands. Their research material is composed of hand-drawn maps by Holocaust eyewitnesses – documents created both in the 1960s and in recent years. They start by summarizing the significance of topology for cultural studies and provide a state-of-the-art reflection on cartography in the context of the Shoah. Then the authors proceed to interpret several of the maps as particular topological testimonies. They conclude by proposing a multi-faceted method of researching these maps, “necrocartography,” oriented on their testimonial, topological and performative aspects. Aleksandra Szczepan - She works as a researcher at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, where she was trained in literary studies and philosophy. -

MAGAZINE Vol

May 1996 MAGAZINE Vol. 1, No. 2 Women in Animation WATCH OUT!! ANIMATION WORLD MAGAZINE Volume 1, No. 2 – May 1996 Editor’s Notebook by Harvey Deneroff 3 Women in Animation and Bill Everson ANIMATION WORLD NETWORK My Small Animation World by Aleksandra Korejwo 4 6525 Sunset Blvd., Polish animator Aleksandra Korejwo muses about life, animation, music, Disney and her salt of many colors. Garden Suite 10 Jim & Stephanie Graziano: An Interview by Harvey Deneroff 8 Hollywood, CA 90028 Jim and Stephanie Graziano have been behind some of the most successful TV shows around. Now DreamWorks has Phone : 213.468.2554 got them. Harvey Deneroff reports. Fax : 213.464.5914 Out of the Animation Ghetto: 11 Email : [email protected] Clare Kitson and Her Muffia by Jill McGreal Over the last few years, Channel 4 has helped put a new face on British animation. Jill McGreal reports how women will lead the broadcaster into series television using the irreverent talents of Candy Guard and Sarah Ann Kennedy. Rose Bond: An Animator's Profile by Rita Street 14 ANIMATION WORLD MAGAZINE Independent animator Rose Bond is known for her use of mythology to explore the problems affecting humanity today. Rita Street explores her philosophy, methodology and her new foray into computer-assisted animation. [email protected] Splendid Artists: Central And 17 PUBLISHER East-European Women Animators by Marcin Gizycki Ron Diamond, President Communist propaganda about the role of women in and out of animation in the USSR, Poland and Czechoslovakia did Dan Sarto, Chief Operating Officer not always coincide with reality. -

University of Derby Reimagining the Blues

UNIVERSITY OF DERBY REIMAGINING THE BLUES: A NEW NARRATIVE FOR 21ST CENTURY BLUES MUSIC Nigel James Martin Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Table of Contents Table of Contents................................................................................................................. i List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iv Declaration.......................................................................................................................... v Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................viii Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1 Aims and Objectives ................................................................................................... 1 Contribution ................................................................................................................ 2 A Note about Terminology ......................................................................................... 4 Chapter Outline........................................................................................................... 7 Contextual & Historical Framework......................................................................... 11 -

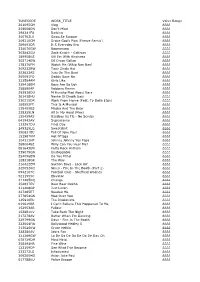

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

The Network of Influences That Shape

THE NETWORK OF INFLUENCES THAT SHAPE THE DRAWING AND THINKING OF FIFTH-GRADE CHILDREN IN THREE DIFFERENT CULTURES: NEW YORK, U.S., MOLAOS, GREECE, AND WADIE ADWUMAKASE, GHANA by Linda E. Kourkoulis Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 10 February 2021 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2021 ABSTRACT THE NETWORK OF INFLUENCES THAT SHAPE THE DRAWING AND THINKING OF FIFTH-GRADE CHILDREN IN THREE DIFFERENT CULTURES: NEW YORK, U.S., MOLAOS, GREECE, AND WADIE ADWUMAKASE, GHANA Linda E. Kourkoulis Using an ecological systems approach, this qualitative study examined how continuously evolving, personal living experiences and the ideologies and attitudes of their material, folk, and school culture come to be (re) presented in the construction of images and meaning in children’s artwork. The research was conducted with three groups of fifth-grade students facilitated by the art teacher at their schools in three different countries: United States, Greece, and Ghana. Data in the form of a set of autobiographical drawings from observation, memory, and imagination with written commentary were created by each participant and supported with responses to questionnaires and correspondences from teachers and parents. The sets of drawings were analyzed in terms of how the drawings reflect the children’s (a) artistic expression as mediated by their interaction with local and media influences and (b) sense of self, agency, or purpose. The findings strongly suggest that style, details, content, and media use assumed a dominant role within the drawings.