The Positioning of Buckfast Tonic Wine Between Acceptability and Transgression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 11 October 2011 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Masterman, R. and Mitchell, J. (2001) 'Devolution and the centre.', in The state of the nations 2001 : the second year of devolution in the United Kingdom. Thorverton: Imprint Academic, pp. 175-196. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.booksonix.com/imprint/bookshop/ Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk 8 Devolution and the Centre' Roger Masterman and James Mitchell INTRODUCTION Much of the debate on devolution before the enactment of the various pieces of devolution legislation was parochial. It had been parochial in concentrat- ing on the opportunities, problems and implications of devolution within Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland; little attention had been paid to devo- lution's impact UK on the as a whole or on the `centre' - Whitehall and Westminster. -

Tavistock Abbey

TAVISTOCK ABBEY Tavistock Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Rumon was originally constructed of timber in 974AD but 16 years later the Vikings looted the abbey then burned it to the ground, the later abbey which is depicted here, was then re-built in stone. On the left is a 19th century engraving of the Court Gate as seen at the top of the sketch above and which of course can still be seen today near Tavistock’s museum. In those early days Tavistock would have been just a small hamlet so the abbey situated beside the River Tavy is sure to have dominated the landscape with a few scattered farmsteads and open grassland all around, West Down, Whitchurch Down and even Roborough Down would have had no roads, railways or canals dividing the land, just rough packhorse routes. There would however have been rivers meandering through the countryside of West Devon such as the Tavy and the Walkham but the land belonging to Tavistock’s abbots stretched as far as the River Tamar; packhorse routes would then have carried the black-robed monks across the border into Cornwall. So for centuries, religious life went on in the abbey until the 16th century when Henry VIII decided he wanted a divorce which was against the teachings of the Catholic Church. We all know what happened next of course, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when along with all the other abbeys throughout the land, Tavistock Abbey was raised to the ground. Just a few ruined bits still remain into the 21st century. -

Offences Involving Buckfast Tonic Wine

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION REQUEST Request Number: F-2010-01013 Keyword: Crime Subject: Offences Involving Buckfast Tonic Wine Request and Answer: This is to inform you that the Police Service of Northern Ireland has now completed its search for the information you requested. The decision has been taken to disclose the located information to you in full. Question 1 A Freedom of Information request showed that Buckfast was mentioned in 5,638 crime reports in Strathclyde Police reports from 2006-2009, equating to three a day on average. One in 10 of those offences were violent and the bottle was used as a weapon 114 times in that period. Under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act, for the period of 2006 to present, please explain how many times Buckfast tonic wine, is mentioned in PSNI crime reports, Answer Since 2006 there have been 102 incidents involving Buckfast Tonic wine. The statistics provided relate to validated crimes where Buckfast was mentioned in the initial report to police and where the bottle was used as a weapon. There may have been other instances where a Buckfast bottle was used and this would have been revealed later as part of the investigation and therefore would not be included. Occurrences involving Buckfast classified as "street drinking" or "rowdy/nuisance persons" were not examined as they are not crimes. Question 2 How many of the offences were of a violent nature. Answer Of the 102 incidents, 8 of these offences could be deemed as violent crime. Violent crime comprises three main offence groupings: offences against the person, sexual offences and robbery. -

NEWSLETTER September 2019

President: Secretary: Treasurer: David Illingworth Nigel Webb Malcolm Thorning 01305 848685 01929 553375 01202 659053 NEWSLETTER September 2019 FROM THE HON. SECRETARY Since the last Newsletter we have held some memorable meetings of which the visit, although it was a long and tiring day, to Buckfast Abbey must rank among the best we have had. Our visit took place on Thursday 16th May 2019 when some sixteen members assembled in the afternoon sunshine outside the Abbey to receive a very warm welcome from David Davies, the Abbey Organist. He gave us an introduction to the acquisition and building of the organ before we entered the Abbey. The new organ in the Abbey was built by the Italian firm of Ruffatti in 2017 and opened in April 2018. It has an elaborate specification of some 81 stops spread over 4 manuals and pedals. It is, in effect, two organs with a large west-end division and a second extensive division in the Choir. There is a full account of this organ in the Organist’s Review for March 2018 and on the Abbey website. After the demonstration we were invited to play. Our numbers were such that it was possible for everyone to take the opportunity. David was on hand to assist with registration on this complex instrument as the console resembled the flight deck of an airliner. Members had been asked to prepare their pieces before-hand and this worked well with David commenting on the excellent choice of pieces members had chosen to suit the organ. We are most grateful to David Davies for making us so welcome and help throughout the afternoon. -

Drinks Menu Gradwell Street

ISSUE 28 BIG PAT AND THE LADS ARE BACK FOR A NEW THRILLING ADVENTURE IN COCKTAILS SUMMER 2019 DRINKS MENU GRADWELL STREET PATTERSONSLIVERPOOL.COM @PATTERSONSARENTWE P4 773 R50N5 LV P001 Club Tropicana AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 KOKO KANU COCONUT RUM, PASSIONFRUIT, PINEAPPLE, LIME, PASSIONFRUIT SYRUP More Than A Feeling AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 ABSOLUT VODKA, BRIOTETTE RHUBARB LIQUEUR, MANZANA VERDE APPLE LIQUEUR, APPLE, CRANBERRY Parma State Of Mind ABSOLUT VODKA, BRIOTETTE VIOLETTE, GOMME, LEMON, BLACK GRAPE SODA Juicy AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 DISARONNO AMARETTO, GIFFARD CHERRY LIQUEUR, VANILLA, CRANBERRY Me and Mr Black HAVANA ESPECIAL RUM, EXPRÈ COFFEE LIQUEUR, ESPRESSO, SUGAR Stage Fright AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 APPLETON SIGNATURE BLEND RUM, LIME, KOKO KANU, BANANA PURÉE, PINEAPPLE, GOMME. Smooth Operator AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 BEEFEATER GIN, GIFFARD WATERMELON, HIBISCUS GOMME, LIME, TONIC. Daddy Kool EVAN WILLIAMS BOURBON, MANGO, LIME, SUGAR, GINGER BEER Notorious F.I.G BEEFEATER GIN, BRIOTETTE RHUBARB, FIG LIQUEUR, CREAM SODA Can You Handle It? BEEFEATER GIN, BUCKFAST TONIC WINE, CAMPARI, ORANGE BITTERS. La La Land PAMPELLE,PROSECCO, CANDYFLOSS Fashion Killer WILD TURKEY STRAIGHT BOURBON, MAPLE SYRUP, ORANGE BITTERS Dark Necessities JAMESONS, BLACK FIRE, ESPRESSO, CINNAMON SYRUP El Mariachi AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 EL JIMADOR BLANCO TEQUILA, KIWI PUREE, GIFFARD WATERMELON LIQUEUR, LIME, SUGAR ALL COCKTAILS £7.5 0 COCKTAILS BAS!C B!TCH3SI Strawberry Daiquiri HAVANA 3YR RUM, GIFFARD FRAISE LIQUEUR, STRAWBERRY PUREE, LIME French Martini ABSOLUT VANILLA, GIFFARD CASSIS LIQUEUR, PINEAPPLE, RASPBERRIES Bellini CHOICE OF PASSIONFRUIT, STRAWBERRY OR BANANA, PROSECCO Mai Tai AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 HAVANA 3 YR, HAVANA ESPECIAL, VELVET FALERNUM, ORGEAT, POMEGRANATE, ORANGE, PINEAPPLE Tommy’s Margarita EL JIMADOR BLANCO TEQUILA, AGAVE, LIME Long Island AVAILABLKE AS PITCHER £15.95 ABSOLUT VODKA, BEEFEATER GIN, HAVANA 3YR RUM, EL JIMADOR BLANCO, LEMON, DIET COKE. -

Jayne Raisborough and Matt Adams: Mockery and Morality

provided by Research Papers in Economics View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Mockery and Morality in Popular Cultural Representations of the White, Working Class by Jayne Raisborough and Matt Adams University of Brighton Sociological Research Online 13(6)2 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/13/6/2.html> doi:10.5153/sro.1814 Received: 1 Feb 2008 Accepted: 13 Oct 2008 Published: 30 Nov 2008 Abstract We draw on 'new' class analysis to argue that mockery frames many cultural representations of class and move to consider how it operates within the processes of class distinction. Influenced by theories of disparagement humour, we explore how mockery creates spaces of enunciation, which serve, when inhabited by the middle class, particular articulations of distinction from the white, working class. From there we argue that these spaces, often presented as those of humour and fun, simultaneously generate for the middle class a certain distancing from those articulations. The plays of articulation and distancing, we suggest, allow a more palatable, morally sensitive form of distinction-work for the middle-class subject than can be offered by blunt expressions of disgust currently argued by some 'new' class theorising. We will claim that mockery offers a certain strategic orientation to class and to distinction work before finishing with a detailed reading of two Neds comic strips to illustrate what aspects of perceived white, working class lives are deemed appropriate for these functions of mockery. The Neds, are the latest comic-strip family launched by the publishers of children's comics The Beano and The Dandy, D C Thomson and Co Ltd. -

The Network RSCM Events in Your Local Area June – October 2016

the network RSCM events in your local area June – October 2016 The Network June 2016.indd 1 16/05/2016 11:17:47 Welcome THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF You can travel the length and CHURCH MUSIC breadth of the British Isles this Registered Charity No. 312828 Company Registration No. summer, participate in and 00250031 learn about church music in 19 The Close, Salisbury SP1 2EB so many forms with the RSCM. T 01722 424848 I don’t think I’ve ever seen quite F 01722 424849 E [email protected] so varied and action-packed an W www.rscm.com edition of The Network. I am Front cover photograph: most grateful to the volunteers on the RSCM’s local Area RSCM Ireland award winners committees, and I hope you will feel able to take up this recording for an RTÉ broadcast, oering. November 2015 How to condense it? Awards, BBC broadcast, The Network editor: Contemporary worship music, Diocesan music day, Cathy Markall Evensongs, Food-based events, Gospel singing, Harvest Printed in Wales by Stephens & George Ltd anthems, Instrumental music, John Rutter, Knighton pilgrimage, Lift up your Voice, Music Sunday, National Please note that the deadline for submissions to the next courses, explore the Organ, converting Pianists, edition of The Network is celebrating the Queen’s birthday, Resources for small and 1 July 2016. rural churches, Singing breaks, Training organists, Using the voice well, Vespers, Workshops, events for Young ABOUT THE RSCM people. Excellence and zeal, I hope. The RSCM is a charity Don’t forget that there is also the triennial committed particularly to International Summer School in Liverpool in August promoting the study, practice and improvement of music at which you can experience many of these things in in Christian worship. -

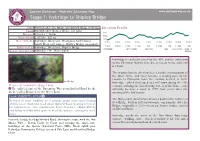

Stage 1-Route-Guide-V3.Cdr

O MO R T W R A A Y D w w k u w . o .d c ar y. tmoorwa Start SX 6366 5627 Ivy Bridge on Harford Road, Ivybridge Elevation Profile Finish SX 6808 6289 Shipley Bridge car park 300m Distance 10 miles / 16 km 200m 2,037 ft / 621 m Total ascent 100m Refreshments Ivybridge, Bittaford, Wrangaton Golf Course, 0.0km 2.0km 4.0km 6.0km 8.0km 10.0km 12.0km 14.0km 16.0km South Brent (off route), Shipley Bridge (seasonal) 0.0mi 1.25mi 2.5mi 3.75mi 5mi 6.25mi 7.5mi 8.75mi 10mi Public toilets Ivybridge, Bittaford, Shipley Bridge IVYBRIDGE BITTAFORD CHESTON AISH BALL GATE SHIPLEY Tourist information Ivybridge (The Watermark) BRIDGE Ivybridge is easily accessed via the A38, and the only town on the Dartmoor Way to have direct access to the main rail network. The original hamlet developed at a handy crossing point of the River Erme, and later became a staging post on the London to Plymouth road; the railway arrived in 1848. Ivy Bridge Ivybridge - which developed as a mill town during the 19th Please refer also to the Stage 1 map. century, utilising the fast-flowing waters of the Erme - only S The official start of the Dartmoor Way is on Harford Road by the officially became a town in 1977, four years after the medieval Ivy Bridge over the River Erme. opening of the A38 bypass. POOR VISIBILITY OPTION a The Watermark (local information) is down in the town near In times of poor visibility or if anxious about your route-finding New Bridge, built in 1823 just downstream from the older Ivy abilities over moorland head down Harford Road, bearing left near Bridge, originally a 13th-century packhorse bridge, passed the bottom to meet the roundabout. -

Devolution and the Centre Monitoring Report

EVOLUTION ONITORING ROGRAMME 2006-08 Devolution and the Centre Monitoring Report January 2009 Robert Hazell The Constitution Unit www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit ISSN 1751-3898 The Devolution Monitoring Programme From 1999 to 2005 the Constitution Unit at University College London managed a major research project monitoring devolution across the UK through a network of research teams. 103 reports were produced during this project, which was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number L 219 252 016) and the Leverhulme Nations and Regions Programme. Now, with further funding from the Economic and social research council and support from several government departments, the monitoring programme is continuing for a further three years from 2006 until the end of 2008. Three times per year, the research network produces detailed reports covering developments in devolution in five areas: Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Englsh Regions, and Devolution and the Centre. The overall monitoring project is managed by Professor Robert Hazell at The Constitution Unit, UCL and the team leaders are as follows: Scotland: Dr Paul Cairney University of Aberdeen Wales: Prof Richard Wyn Jones & Prof Roger Scully Institute of Welsh Politics, Aberystwyth University Northern Ireland: Professor Rick Wilford & Robin Wilson Queen’s University, Belfast English Regions: Prof Alan Harding & Dr James Rees IPEG, University of Manchester The Centre: Prof Robert Hazell, The Constitution Unit, UCL The Constitution Unit and the rest of the research network is grateful to all the funders of the devolution monitoring programme. All devolution monitoring reports are published at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution- unit/research/devolution/devo-monitoring-programme.html Devolution and the Centre Monitoring Report January 2009 Robert Hazell Devolution and the Centre Monitoring Report January 2009 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 5 1. -

An Investigation Into the Environmental Impact of Off-License Premises on Residential Neighbourhoods

An Investigation into the Environmental Impact of Off-license Premises on Residential Neighbourhoods November 2007 Alasdair J. M. Forsyth, Neil Davidson* and Jemma C. Lennox Scottish Centre for Crime & Justice Research The Glasgow Centre for the Study of Violence Glasgow Caledonian University * Now at the Scottish Institute for Policing Research, School of Social Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN 1 Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Donna Hughes for her assistance during observational fieldwork, Leona Cunningham for assistance during piloting, Stephen Lopez and Catherine McGuinity for help with project administration, Andrew McAuley for providing health statistics, Steve Parkin for information on drug-related litter, Pauline Roberts for graphical advice, Alcohol Focus Scotland for their continued support during this research and the anonymous shop workers who participated in this research. 2 Contents Page Introduction Background 4 Aims 10 Methods Research Design and Procedures 11 Selection of Study Area 15 Results Observations of Neighbourhood Convenience Stores 19 Interviews with Shop Servers 28 Survey of Alcohol-related Detritus 39 Spatial Relationships between Shops and Alcohol-related Incivilities 58 Conclusions Discussion 81 Limitations and Future Research 94 Key Implications and Recommendations 99 Bibliography References 103 Appendices Shop Observation Schedule 114 Shop Server Interview Topic Guide 118 Items of Alcohol-related Detritus Recording Form 119 Neighbourhood Profiles 120 Brand Identified Items of Alcohol-related Detritus 121 3 Introduction Background In recent times there has been a great deal of concern about levels of anti-social behaviour across the UK (Home Office, 2005; House of Commons, 2005; Scottish Parliament, 2003). Several reports have investigated the role of alcohol as a potentially important contributor to this problem (Babb, 2007; Engineer et al, 2003; Finney, 2004; Home Office, 2001; Matthews et al, 2006; Richardson & Budd, 2003; Travis, 2004). -

Advent 2015 Two Recent Publications: a Book and a Film

Advent 2015 Two Recent Publications: A Book and a Film Monks have long been known for their diverse tal- on the afternoon of Sunday, September 13, attended ents and interests: teachers, farmers, writers, artists. by a number of Fr Stephen’s former students and Among the last-named was Fr Stephen Reid of our other friends of the abbey. It is available in our gift community, who at the time of his death in 1989 had shop for $20, and can be ordered by mail for an produced a remarkable number of sculptures and additional four dollars to cover shipping costs. paintings. In the past few years, an art critic named We think our readers would also like to know Bruce Nixon has been working on a publication that of a documentary about Benedictine life that has offers a thoughtful, carefully researched interpretive been produced for the Catholic French television text that considers Fr Stephen’s art in the context channel KTO, founded in 1999 by the late cardinal- of his life as a monk. Titled A Communion of Saints, archbishop of Paris, Jean-Marie Lustiger. Titled Le this forty-page illus- Temps et la règle bénédictine, this 52-minute film was trated catalog includes first telecast in December, 2014. The director, Patrice photographs made in Cros, has twice visited St Anselm’s and hopes accordance with the to produce English-language documentaries on archival standards of this and similar Benedictine topics, such as work, museum documenta- community, authority, and poverty. If any of our tion and so serves to readers have suggestions of sponsors who could preserve the legacy finance such a project, please let Abbot James know. -

Nations and Regions: the Dynamics of Devolution

Nations and Regions: The Dynamics of Devolution Quarterly Monitoring Programme Devolution and the Centre Quarterly Report February 2003 by Guy Lodge The monitoring programme is jointly funded by the ESRC and the Leverhulme Trust 1 Contents Contents Key Points 1 Devolution and Westminster 1.1 House of Lords Debate on the Constitution 1.2 New Breakaway Conservative Party 1.3 House of Lords Constitution Committee 1.4 Regional Assemblies (Preparations) Bill 1.5 Parliamentary Questions to the Wales Office 1.6 The Work of the Territorial Select Committees 1.7 The Work of the Grand Committees 1.8 Select Committee on the Lord Chancellor’s Department 1.9 Minority Party Representation on Select Committees 1.10 Barnett Formula 1.11 House of Lords Reform 2 Devolution and Whitehall 2.1 Edwina Hart accuses Whitehall of obstructing National Assembly 2.2 Helen Liddell Announces Decision on MSP Numbers 2.3 The Future of the Territorial Offices 3 Intergovernmental Relations 3.1 Meeting of JMC (Europe) 3.2 British-Irish Council Summit 3.3 Meeting of the British-Irish Council Environment Group 3.4 Meeting of the British-Irish Council Drugs Group 3.5 UK Government and the Devolved Bodies Launch the Animal Health and Welfare Strategy Consultation 2 Key Points • Assembly Finance Minister Edwina Hart criticises Whitehall civil servants • Lord Norton debate on the British Constitution in the House of Lords • Helen Liddell announces that the number of MSPs will remain at 129 in the outcome of the consultation on the size of the Scottish Parliament. • House of Lords Constitution Committee publishes Devolution: Inter- Institutional Relations in the United Kingdom • House of Lords debate on the Barnett Formula • Second Reading and Committee Stage of the Regional Assemblies (Preparations) Bill • Seven options for Lords Reform fail to gain a majority.